Reuters

ReutersThe road to Idlib, a remote corner in north-west Syria, still has the signs of the old front lines: trenches, abandoned military positions, rocket shells and ammunition.

Until a little more than a week ago, this was the only area in the country controlled by the opposition.

From Idlib, rebels led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, launched an astonishing offensive that toppled Bashar al-Assad and ended his family’s five-decade dictatorship in Syria.

As a result, they have become the country’s de facto authorities and appear to be trying to bring their way of governing to the rest of Syria.

In Idlib’s city centre, opposition flags, with a green stripe and three red stars, were flying high in public squares and being waved by men and women, old and young, in the wake of Assad’s removal. Graffiti on walls celebrated the resistance against the regime.

While destroyed buildings and piles of rubble were a reminder of the not-so-distant war, renovated houses, recently opened shops and well-maintained roads were testament that some things had, indeed, improved. But there were complaints of what was seen as heavy-handed rule by the authorities.

When we visited earlier this week, streets were relatively clean, traffic lights and lamp-posts worked, and officers were present in the busiest areas. Simple things absent in other parts of Syria, and a source of pride here.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCHTS has its origins in al-Qaeda but, in recent years, has actively tried to rebrand itself as a nationalist force, distant from its jihadist past and intent on removing Assad.

As fighters marched to Damascus earlier this month, its leaders spoke about building a Syria for all Syrians. It is, however, still described as a terrorist organisation by the US, the UK, the UN and others, including Turkey, which backs some Syrian rebels.

The group took control of most of this region, home to 4.5 million people, in 2017, bringing stability after years of civil war.

The administration, known as the Salvation Government, runs water and electricity distribution, garbage collection and road pavement.

Taxes collected from businesses, farmers and crossings with Turkey fund its public services – as well as its military operations.

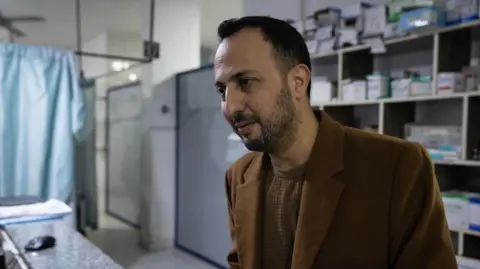

“Under Assad, they used to say that Idlib was the forgotten city,” said Dr Hamza Almoraweh, a cardiologist, as he treated patients in a hospital set up in an old post office warehouse.

He moved from Aleppo with his wife in 2015 when the war there intensified, but was not planning to return, even with the city under rebel control.

“We’ve seen a lot of development here. Idlib has a lot of things that it didn’t have under the Assad regime.”

As it moderated its tone, seeking to obtain international recognition amid local opposition, HTS revoked some of the strict social rules it had imposed when it came to power, including dress codes for women and a ban on music in schools.

And some people cite recent protests, including against taxes imposed by the government, as proof that a certain level of criticism is tolerated, in contrast with the repression of the Assads.

“It’s not a full democracy, but there’s freedom,” said Fuad Sayedissa, an activist.

“There were some problems at the beginning but, in the last years, they’ve been acting in a better way and are trying to change.”

Originally from Idlib, Sayedissa now lives in Turkey, where he runs the non-governmental organisation Violet. Like thousands of Syrians, the fall of Assad meant he could visit his city again – in his case, for the first time in a decade.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCBut demonstrations have also been held against what some say is authoritarian rule. To consolidate power, experts say, the group targeted extremists, absorbed rivals and imprisoned opponents.

“How the government will act in the whole Syria is a different story,” Sayedissa said. Syria is a diverse country and after decades of oppression and violence perpetrated by the regime and its allies, many are thirsty for justice. “People are still celebrating, but they’re also worried about the future.”

We tried to interview a local official, but were told all of them had gone to Damascus to help in the new government.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCAn hour’s drive from Idlib, in the small Christian village of Quniyah, the church bells rang for the first time in a decade on 8 December to celebrate Assad’s removal.

The community, near the Turkish border, was bombed during the civil war, which started in 2011 when Assad crushed peaceful protests against him and many of its residents fled.

Only 250 people remained.

“Syria is better since Assad fell,” said Friar Fadi Azar.

Lee Durant/BBC

Lee Durant/BBCThe rise of Islamists, however, has raised fears that minorities, including Assad’s Alawites, could be at risk, despite the messages from HTS reassuring religious and ethnic groups that they would be protected.

“In the last two years, they [HTS] started changing… Before, it was very hard,” Friar Azar said.

Properties were confiscated and religious rituals restricted.

“They gave [our community] more freedom, they called on other Christians who were refugees to come back to take their land and homes back.”

But is the change genuine? Can they be trusted? “What can we do? We have no other option,” he said. “We trust them.”

I asked Sayedissa, the activist, why even opponents were reluctant to criticise the group.

“They’re now the heroes… [But] we have red lines. We’ll not allow dictators again, Jolani or any other,” he said, referring to Ahmed al-Shara, the HTS leader who dropped his nom de guerre Abu Mohammad al-Jolani after coming to power.

“If they act as dictators, the people are ready to say no, because they now have their freedom.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours