Fashion

Lila Moss Brings a Quiet Mood to Adanola Spring 2026

Fashion

Chic Fashion Pairings for a Photoshoot with Your Partner

Fashion

H&M Studio Essentials Goes Back to Basics for Spring 2026

Fashion

What Cross-Country Moving Teaches You About Personal Style

A cross-country move has a way of cutting through noise. It is not symbolic. It is practical. Boxes cost money. Trucks have limits. Time runs out faster than expected. At some point, every item you own is held up and judged with a straightforward question: Is this worth taking with me?

That question changes how you see your belongings, especially your clothes. Personal style stops being aspirational and starts being honest. What you keep reveals what you actually wear, rely on, and feel like yourself in, moving forces clarity in a way few other life events do.

This is not about minimalism for its own sake. It is about alignment. When space, money, and energy are finite, style becomes less about options and more about intention.

Moving Strategy: How Logistics Force Style Decisions

Even before anything touches a box, a plan is already in motion. Moving things across the country is expensive. Each additional weight adds up fast. That’s why an experienced cross-country moving company doesn’t just move belongings. It forces decisions. Now, here’s something. A coat sitting alone in the closet isn’t taking up space anymore. It carries a price tag.

Here’s how it works. Personal taste connects with real-life needs. A shift happens in how you see things. Pieces start forming into clusters. What matters is how much something is worth, how often you reach for it, plus how deeply it affects your emotions. Certain items instantly earn a place. Others stay stuck in doubt, caught between choices, until life finally decides for them.

Habits show up through the routine. A shirt worn once sits in a box afterward. Outfits purchased just for a single date. Shoes held tight even though they’ve lost their reason. Things that used to show who you really were. When life moves on, there’s no room to keep what might have been. Choices become necessary.

Under pressure from weight, choice becomes practical. In the end, it’s not about fit theories. It’s results in actual settings.

Editing Ruthlessly: What You Learn When You Can’t Take Everything

Finding flaws never sits well. At the beginning, it looks like giving something up. Still, that act also shows truth.

Take away too much, and things start showing up. Silhouettes catch your eye, ones you come back to frequently. There’s fabric here you already know works. Repeated hues jump out, too. The imaginary objects become obvious fast. These need a reason behind them.

Away from home, how someone dresses shows where their real world fits. Letting that difference go is hard. Still, it might loosen what holds you back.

Left behind isn’t luck. It quietly tells how you’ve lived. Slowly, clarity comes; your look never really changed. Beneath all those choices, it sat quietly.

Climate, Culture, and Lifestyle Shifts

Outside shifts affect fabric behavior. Storms alter material response. Societal norms reshape object meaning. When life changes, what we need every day often shifts too.

One season’s clothes can seem out of place elsewhere. That doesn’t prove your choices were bad, just how context shapes taste. What stays central shifts how it shows up.

What stands in the way isn’t swapping everything right away. It’s about translating what already exists into something new. Over time, you see what pieces of your look truly count, while others come just by chance. Often, it’s the way things are laid out, how clean or full they look, or whether they bring calm or attention that makes the difference, not the exact items themselves.

Shifting places trains adaptability, yet keeps nothing lost. Not disappearing entirely matters just as much as refusing transformation does. Acting with purpose shapes each shift.

Quality Over Quantity Becomes Non-Negotiable

When shifted, weak materials often fail to withstand the load. Shipped versions might bend, crack, or seem useless once the room runs thin. Strong constructions last longer. These keep their place by reason.

Such a change unfolds on its own. After managing each piece, packing, unpacking, and making room, the real character shows up. Not some idea pulled from books, a truth shaped by doing.

What sticks changes, too. Things that actually help start meaning more than ones that seem nice at first glance. What matters shifts toward what works without fail.

What stays changes size but gains depth over the years. This happens through learning rather than control.

Rebuilding Intentionally After the Move

Once the shift occurs, some feel pressured to act quickly. A fresh place means new shops, maybe even a different life. Yet slowing down can make sense. Rushing may miss deeper reasons behind the change.

What’s missing in your clothes matters more than you think. That space reveals real needs today, shaped by where you are and what you do. Buying fast to cover gaps often ends poorly, like chasing shadows.

Start by watching how things unfold. See which moments you later crave. Notice the shortcuts, the tweaks, the borrowed ideas. Let reality shape what comes next.

Nowadays, how someone dresses turns into something like a framework. Not so much about reacting. More about thinking ahead. Buying things now slips under the radar. Feels firmer, somehow.

Personal Style as a System, Not a Closet

Cross-country moving reframes style as infrastructure. It supports your life. It should reduce friction, not add to it.

When you see style this way, accumulation loses its appeal. Efficiency matters. So does coherence. You stop shopping for novelty and start refining a framework.

This approach extends beyond clothing. The same principles apply to how you organize your home, your time, and your priorities. Moving makes these connections visible.

Style stops being decorative. It becomes functional self-knowledge.

Conclusion: Moving as a Shortcut to Self-Knowledge

Major transitions accelerate learning. Cross-country moving compresses years of reflection into weeks of decision-making.

By the end, you own less. But you understand yourself more clearly. Your personal style feels steadier, not because it is fixed, but because it is rooted.

What you carry forward is not just a wardrobe. It is discernment. And that is something worth moving with.

Fashion

Coffee Break: Navy Leather Belt

This post may contain affiliate links and Corporette® may earn commissions for purchases made through links in this post. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Navy belts can be hard to find, but I really like this one from Talbots.

Now, of course, you don’t have to wear a navy belt with navy pants — the general rule I’ve always heard is to match your belt to your shoes. I often think of tan leather as great to wear with navy, but you can obviously wear black with navy also!

(We’ve also talked about what color tights to wear with navy skirts!)

Still, if you’re on the hunt for a navy leather belt it can be tricky to find one. This one from Talbots looks perfect — and I like that the belt buckle is covered in the same leather so it’s muted.

The belt is $79.50 at Talbots, and comes in sizes XS-XL and in colors black and brown. You can take 25% off today (discount in bag).

Sales of note for 1/27:

Fashion

What Are Your Work Outfit Workhorses?

This post may contain affiliate links and Corporette® may earn commissions for purchases made through links in this post. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Here’s something we haven’t discussed in too long that’s always a fun topic: what are your work outfit workhorses? Which accessories, third pieces, and more have you found to be surprisingly versatile and otherwise something you reach for more than you thought you would?

When we last discussed surprise basics for workwear and workhorses for your working wardrobe, I’ve called out my love of colorful purses, olive-colored pants, a good watch, and of course purple heels as things that I was surprised to find myself wearing a ton.

I’ve also written of other things that are outside the usual “must have” lists, including very light gray pants instead of summer whites, velvet blazers for festive in-office holiday lunches, huggie earrings like these, light blue blazers, and purple pumps. It also came up a bit with our discussion of light blue suits, with lots of readers noting that they often wear a pair of colorful blue trousers or a colorful blue blazer (but not together).

Those discussions were a while ago, though, so let’s discuss — what are you finding a surprise workhorse in 2026? (Has anything that you used to love, like olive pants, become less versatile with the fashions of today?) What items have you had a hard time finding, and what are you replacing them with?

Fashion

Cardi B Storms Saturday Night Live Wearing Rowen Rose Burgundy Patent Look, Custom Bryan Hearns, and Leather Candice Cuoco

Cardi B delivered a full fashion rollout during her appearance on Saturday Night Live, stepping out in a series of bold looks that carried her from arrival to performance to post-show exit.

The rapper first arrived at Rockefeller Center wearing a burgundy patent ensemble by Rowen Rose. The high-shine look featured a belted jacket with a deep neckline paired with a coordinating midi skirt, styled with black pointed-toe boots and a mini top-handle Hermes bag. The glossy finish and structured tailoring gave the entrance look a sharp, statement-making presence. The outfit was styled by Kollin Carter.

For her SNL performance, Cardi B changed into a custom leather look by Candice Cuoco, again styled by Kollin Carter. Cuoco said, “This one was fun. I drew [inspiration] from Cardi and her love for her culture, I drew inspo from the beautiful Dominican folkloric pollera. Creating custom embossed hand painted floral leather corset with leather ruffles throughout the skirt and corset. Mixed in with tiers of pleated silk chiffon, ruffled laces, satin ribbons and skirt layers of flounce cut leather for the tiers of the skirt.” Cuoco also shared that part of the look was constructed at KidSuper Studios.

Cardi also performed in a custom Bryan Hearns look, replete with rings and leather details:

After the show, Cardi B greeted fans wearing a custom trench coat by Bryan Hearns. The outerwear maintained the evening’s leather-forward aesthetic while offering a more streamlined silhouette for her exit, closing out the night with another polished fashion moment.

Hot! Or Hmm..?

🎥: NBCSNL

Fashion

The Cold Weather Investment Edit

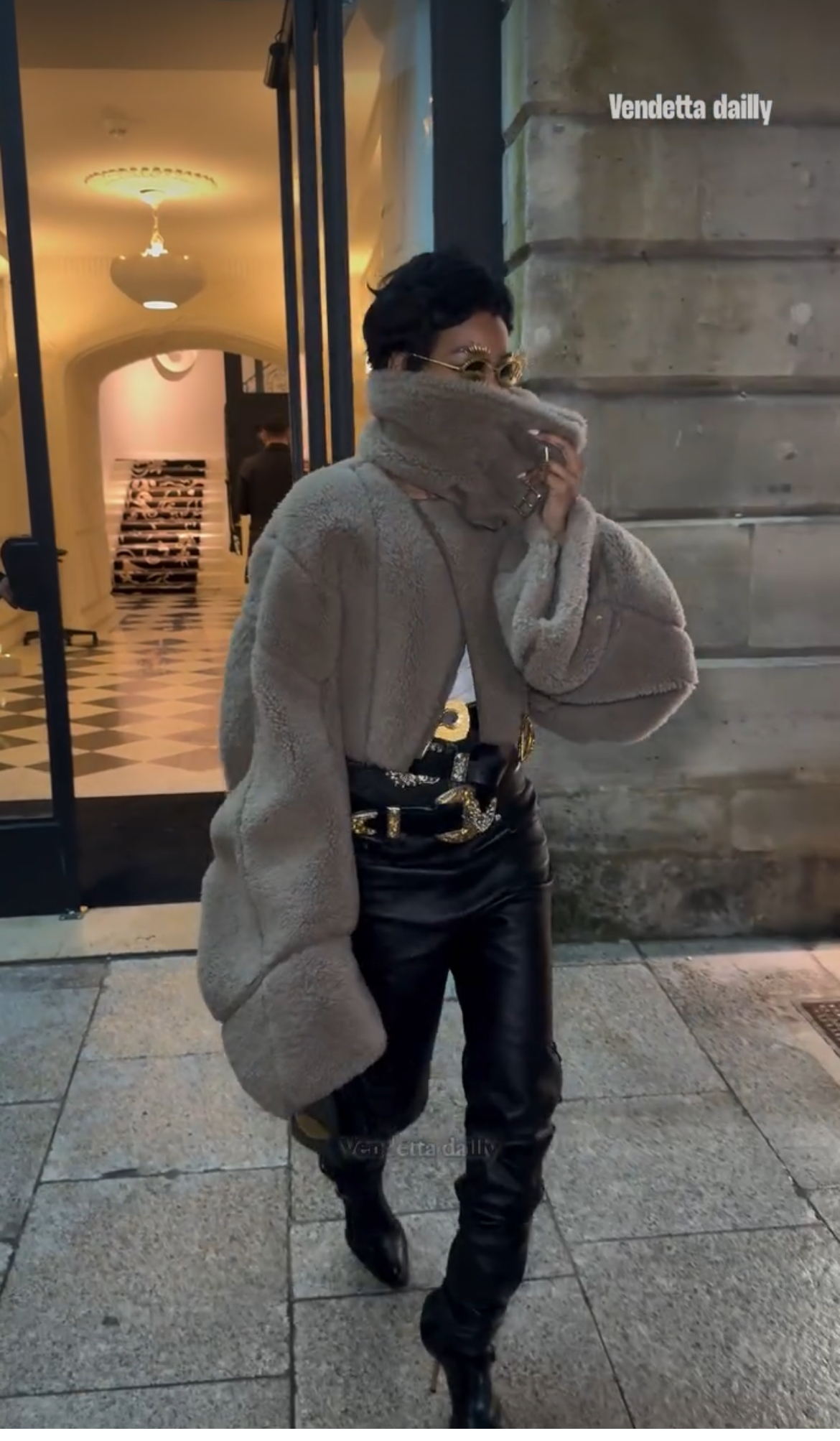

Max Mara Coat (old, similar here and here), Toteme Sweater (old, similar here, here and here), La Ligne Jeans, Le Monde Beryl Boots, Similar Scarf (and here), Agnelle Gloves, Dior Sunglasses

Cold weather challenges wardrobes to earn their credibility. This edit centers on pieces with presence, outerwear and layers defined by material, construction, and detail. These aren’t everyday basics. They’re specialty buys: shearling and calf hair that bring texture, tailored coats with intentional proportion, statement knits, and jackets finished with trims, embroidery, or sculptural shapes. Each piece offers something beyond function, whether it’s craftsmanship, fabric story, or silhouette.

The focus is on quality you can see and feel. Substantial weight. Thoughtful construction. Finishes that elevate even the most minimal outfit. A great coat should hold its own. A sweater should bring dimension through color, stitch, or pattern. Accessories should introduce contrast through texture and form.

These are pieces you buy now, wear immediately, and return to next winter without hesitation, investment dressing built for longevity, not a single season. Designed for repeat wear, they move easily between polished looks and relaxed days while maintaining their character. Let the details carry the season.

Leopard Hat

This leopard print hat brings depth to simple looks; works equally well with tailoring, denim, or evening layers.

Fur Trim Parka

An oversized cotton parka with dropped shoulders and removable shearling collar, blending relaxed tailoring with utilitarian polish.

Fashion

Top 5 Looks of January: Cardi B in a Burgundy Patent Rowen Rose Look, Elton John in a Lime Green Set, Teyana Taylor in Schiaparelli & More!

It’s a new year and the month of January set the tone for fashion in 2026 with modern silhouettes and luxurious fabrics. We’ve curated our ‘TOP 5’ looks of the month based on views and impressions so check out who made the cut!

Cardi B in Rowen Rose- 2,496,054 Views

We love Cardi B dowwwwn, and her latest appearance on Saturday Night Live solidified her as a style trailblazer. The ‘Imaginary Players” rapper arrived to the SNL studio in a patent leather burgundy look that was one for the books. One thing about Cardi B’s team is that they’re going to EAT every single time, and this look was absolutely sickening.

Elton John in Lime Green Set- 1,126,052 Views

The legend himself Elton John was captured in Paris this past month alongside his partner David Furnish in a lime green pleated set that was ravishing on the music star. Known for his flamboyant style, he’s fearless when it comes to wearing bold colors, statement outfits, and extravagant accessories. Elton layered his lime green ensemble over a black crewneck shirt, and styled it with an oversized diamond cross and black shades. Opting for comfy footwear, his sneakers with lime green laces complimented his outfit.

Teyana Taylor in Schiaparelli – 1,055,677 Views

Teyana Taylor is exactly who she thinks she is, and while in Paris, the multifaceted artist was photographed in a full Schiaparelli look that was to die for. Her asymmetrical fur coat was characterized with long sleeves, and gave main character energy with a detachable collar. Her layered belts were right on trend with what we’ve seen on the runways, and her black leather pants added an edgy element. Not to mention her gold eyelash Schiaparelli sunglasses that were a game changer.

Izzy Azalea in a Black Dress- 801,589 Views

Australian artist Iggy Azalea has been missing in action since her departure from the music scene. During the Grammys festivities, she was photographed at an event in a black bodycon dress that was hip-hugging, and seductive. With a super long blonde sleek “buss down“, and a mean face beat that flawlessly enhanced her features, Iggy looks like she’s ready to make a returning debut.

Oladria Carthen In Rahul Mishra- 662,672 Views

Olandria! Olandria! Olandria! If anyone has been stepping on people’s necks, it’s this girl who is proving to be the perfect muse. During Paris Haute Couture Week, Olandria looked like a masterpiece in a Rahul Mishra ensemble that was a work of art. Her architectural dress told a rich story, and we all know that when beauty and art collides, it can become a monumental moment.

What say you? Hot! Or Hmm…?

Photo Credit: IG/Reproduction, @freshmadeit, @jairo.media, @getty, @backgrid

Fashion

Blast from the Past: February 2

This post may contain affiliate links and Corporette® may earn commissions for purchases made through links in this post. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

I was thinking, how I’m always amused to stumble on older pieces that we’ve featured here on Corporette® … sometimes they still look good, or I remember liking them. Other times, the styling or the featured piece of clothing is just… fug.

Anyway, I started thinking… it might be fun to share some previously featured pictures with you guys, and discuss — would you wear these items today? If so, how would you style them in 2025? If you’ve replaced items like this in your closet, what are you wearing instead of them?

First up, some of the things we featured on February 2 over the years…

What We Wore to Work in February (Over the Years)

2009: A Kimono Dress from Aquascutum

I feel like there were a lot of “kimono dresses” around this time period — there was a specific one the readers loved that I’m totally blanking on. Hmmn. (Maybe this one from ASOS?)

Anyway: we featured this gorgeous dress from Aquascutum was at NET-A-PORTER for $1115. Maybe it’s me but I still think it’s absolutely gorgeous, and unique enough that it wouldn’t be overly dated.

Aw, there were exactly 7 comments on the Splurge TPS report. Early days for the blog!

Similar Dresses with Cool Structural Details

2010: Eileen Fisher Stand Collar Jacket

This was an early sweater jacket — made from lambswool and cashmere, with that regular blazer shape. Sweater jackets had been a bit shrunken in the previous years (I had one from Iisli that I loved so much I took engagement pictures in it — similar to this one), so this longer length one was a bit different so we featured it. (I blame Wedding Bee for the weird poses.)

Similar Sweater Blazers for 2026

I usually stick to the morning workwear reports for these (originally called TPS reports because there was an obscure reference to the movie Office Space, then we went with “The Personal Shopper,” and then we dropped all of it for “Workwear Report”) — ANYWAY this brown leather bag was featured somehow on a Pin or something and, for years, we would get traffic back to the blog because of this tote. (The good old days!) It’s still really gorgeous…

Similar North/South Leather Totes

We rounded up north/south totes a while ago — if you’re looking for something extremely similar, check out this affordable leather bag or this Amazon seller.

Some of our favorite north-south totes for work in 2026 include options from Madewell, Cuyana, BÉIS, MZ Wallace, Tumi, and Everlane — this convertible north-south tote from Bellroy looks great also.

2012: Cardigan From Charles Tyrwhitt

Aw, I haven’t thought about Charles Tyrwhitt in years, and a quick check tells me they’ve stopped making women’s wear entirely. For a while though they were sort of a competitor to Brooks Brothers for button-front shirts and the like. This merino cardigan was on a great sale, $200 to $60.

Cardigans We Love in 2026

2015: Narcisso Rodriguez Blazer

Hmmn… I’m not a fan of this one. I suppose it is unusual, though. The blazer was $2195 at Nordstrom, as we noted in the post.

2016: Pintuck Dress from Reiss

I loved this Reiss dress then and I still love it now. It actually reminds me of a super old Calvin Klein dress that had a similar starburst pattern and was around for years. (It’s still at Amazon in lucky sizes!)

2017: Hideous Ponte Blazer

Yeah… I’m not sure what I was thinking with this one, because there are much better blazers to be found for under $50. I do like the color here, and I suppose it was trendy at the time…. This was an LC Lauren Conrad Ponte Blazer at Kohl’s.

Affordable Blazers Under $50

2018: Satin Shell from Loft

Gosh… I’m not in love with this one either. The buttons seem out of place, and as far as sleeveless tops go I really don’t like it. But: it was Loft, and was Frugal Friday, so there you go. (Interestingly, in the post we mentioned that Loft Plus was coming soon, with sizes up to 26 — I had completely forgotten they had plus sizes for a hot second.)

I’ll post some of our preferred sleeveless shells below, but do note that we also just rounded up shirts with interesting collars late last year.

Sleeveless Shells in 2026

2021: Sheath Dress from Of Mercer (RIP)

Of Mercer has unfortunately gone out of business, but this dress reminds me a lot of what they did right — interesting details but still appropriate for work. If memory serves they offered sizes up to 22 at least, and the occasional maternity dress. You can still find the brand on the resale sites… we featured it in 2021, when Elizabeth was still frequently working from home.

Asymmetrical Power Dresses in 2026

One of the classic asymmetrical power dresses is the Black Halo Jackie dress; this affordable option at Nordstrom Rack also works. Stay tuned for a roundup of more!

2022: Athleta Pants

Comfort was the name of the game in 2022 as people returned to the office (well, some did)… these Eastside pants from Athleta were popular among readers.

For 2026, I’ve heard more chatter about these Athleta pants or these…

More Pull-On Comfortable Work Pants

Any favorites you remember from February workwear reports, readers?

(Psst: you can see previous installments of this occasional series here!)

Fashion

Timeless Dining – Newbridge Silverware Cutlery Sets 2026

Transform every meal into a celebration with the 2026 Newbridge Silverware Cutlery Sets 2026 collection. Renowned for their exquisite craftsmanship since 1934, Newbridge Silverware offers a range of cutlery that marries Irish heritage with modern durability. Whether you are looking for the robust elegance of 18/10 stainless steel for daily use or the heirloom quality of silver-plated patterns for formal hosting, this year’s lineup has a set for every home. From the intricate Celtic knot designs to the classic Kings silhouette, discover why Newbridge remains the gold standard for dining excellence.

Chandra Stainless Steel 44 Piece Giftpack (Shop Now)

Celtic Stainless Steel 24 Piece Gift Pack (Shop Now)

Kings Stainless Steel 44 Piece Gift Pack (Shop Now)

Celtic Silver Plated Pastry Set Pack x 7 (Shop Now)

Chandra Stainless Steel 24 Piece Giftpack (Shop Now)

Kildare Stainless Steel 44 Piece Gift Pack (Shop Now)

Silver Plated 24 Piece Cutlery Set – Kings (Shop Now)

Kings Silver Plated 6 Piece Tea Spoon Set (Shop Now)

Kings Silver Plated 7 Piece Place Set Pack (Shop Now)

For any questions/feedback regarding the above mentioned products/brands,

please do contact us anytime by clicking here

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoSmart energy pays enters the US market, targeting scalable financial infrastructure

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Software stocks enter bear market on AI disruption fear with ServiceNow plunging 10%

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoWhy is the NHS registering babies as ‘theybies’?

-

Crypto World5 days ago

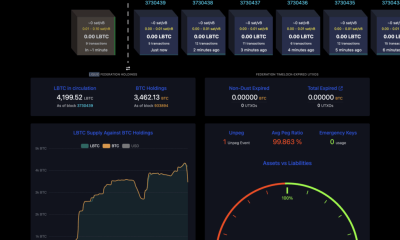

Crypto World5 days agoAdam Back says Liquid BTC is collateralized after dashboard problem

-

Video1 day ago

Video1 day agoWhen Money Enters #motivation #mindset #selfimprovement

-

NewsBeat5 days ago

NewsBeat5 days agoDonald Trump Criticises Keir Starmer Over China Discussions

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoU.S. government enters partial shutdown, here’s how it impacts bitcoin and ether

-

Politics2 days ago

Politics2 days agoSky News Presenter Criticises Lord Mandelson As Greedy And Duplicitous

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoSinner battles Australian Open heat to enter last 16, injured Osaka pulls out

-

Fashion4 days ago

Fashion4 days agoWeekend Open Thread – Corporette.com

-

Crypto World3 days ago

Crypto World3 days agoBitcoin Drops Below $80K, But New Buyers are Entering the Market

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoMarket Analysis: GBP/USD Retreats From Highs As EUR/GBP Enters Holding Pattern

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoKuCoin CEO on MiCA, Europe entering new era of compliance

-

Business4 days ago

Entergy declares quarterly dividend of $0.64 per share

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoShannon Birchard enters Canadian curling history with sixth Scotties title

-

NewsBeat20 hours ago

NewsBeat20 hours agoUS-brokered Russia-Ukraine talks are resuming this week

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoGAME to close all standalone stores in the UK after it enters administration

-

Crypto World5 hours ago

Crypto World5 hours agoRussia’s Largest Bitcoin Miner BitRiver Enters Bankruptcy Proceedings: Report

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoWhy AI Agents Will Replace DeFi Dashboards

-

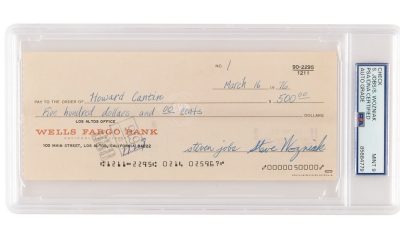

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoVery first Apple check & early Apple-1 motherboard sold for $5 million combined