Entertainment

10 Movies From 1992 That Are Now Considered Classics

1992 was one of those deceptively stacked years that didn’t announce its greatness all at once. It represented a moment where Hollywood spectacle, literary adaptations, political biography, genre reinvention, and abrasive indie cinema were all colliding in productive ways. Most important of all, a new generation of filmmakers was ripping up all the old rules.

The result was an interesting collection of bangers. Several of these films were commercially successful on release, but many were controversial, divisive, or misunderstood. With time, however, their ambition has become unmistakable. The titles below represent the best of the best of 1992.

10

‘Candyman’ (1992)

“Be my victim.” While occasionally a little rough around the edges, Candyman‘s sheer density of frights earns it a place in the horror pantheon. Story-wise, it focuses on a graduate student (Virginia Madsen) researching urban legends who becomes entangled with the myth of a supernatural killer said to appear when his name is spoken five times into a mirror. That sounds like fairly standard genre stuff, but what initially plays like a conventional slasher gradually reveals itself as something far more ambitious.

The movie’s themes are just as important as the scares, grounding the supernatural in real social divisions. In particular, Candyman uses horror to explore race, class, and the way violence is mythologized and erased within American cities. The killer (Tony Todd) is not just a monster, but a symbol shaped by collective fear and historical injustice. Todd’s fantastic performance does most of the heavy lifting. (That scene with the bees! Talk about being committed to the role.)

9

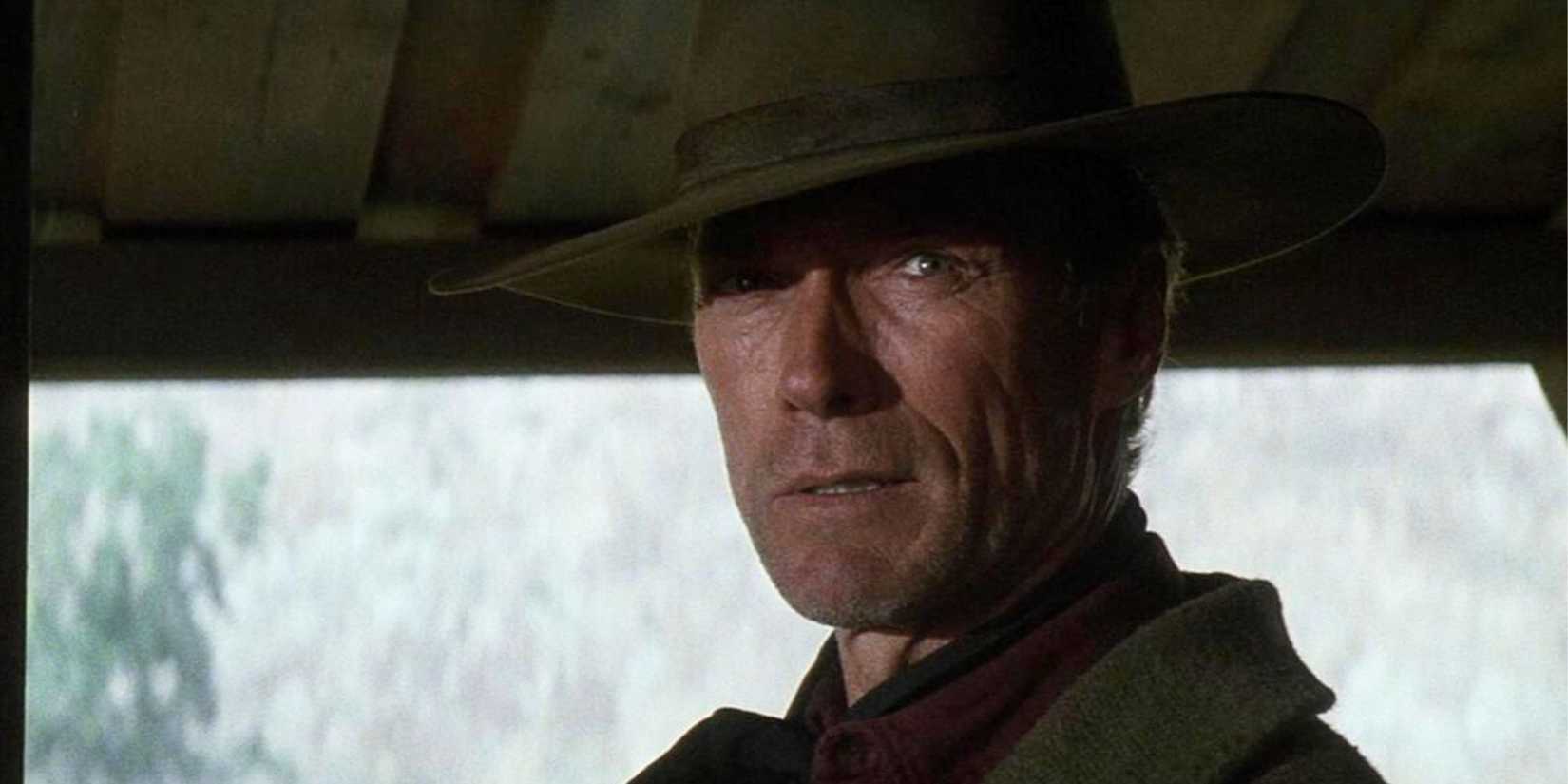

‘Unforgiven’ (1992)

“Deserve’s got nothing to do with it.” Clint Eastwood consciously conceived of Unforgiven as his final Western, his closing statement on the genre that made him a star. Here, he plays an aging former outlaw pulled back into violence for one last job, using the character to pretty much dismantle the mythology of the American Western. While the plot centers on a bounty offered for the men who disfigured a prostitute, the story quickly becomes an interrogation of legend, reputation, and moral consequence.

Eastwood was in a unique position to tell this story. His direction treats the genre with both familiarity and skepticism, acknowledging its power while stripping away its lies. Most strikingly, Unforgiven refuses to glamorize killing. The violence in it is clumsy, terrifying, and permanent, leaving emotional wreckage in its wake. The result is a moving farewell to heroic fantasy and a reckoning with what those stories concealed.

8

‘The Crying Game’ (1992)

“I know who you are.” The Crying Game is simultaneously a political thriller involving an IRA kidnapping and an intimate drama about identity, guilt, and desire. The plot follows a British soldier (Forest Whitaker) captured during a conflict in Northern Ireland and the unexpected emotional bond that forms between captor and captive. After the soldier’s death, the story shifts to London, where loyalty and memory blur into obsession. The narrative twists are hard-hitting, yet what really sets the movie apart from others in the genre is its empathy.

The Crying Game takes an intelligent, sensitive approach to its material. It treats identity as fragile and deeply personal, resisting sensationalism even when dealing with taboo subject matter (The Troubles in Ireland were still underway when it was released, making it somewhat controversial). Over time, however, the movie’s reputation has matured beyond shock value, recognized instead as a thoughtful exploration of how political violence spills into private lives.

7

‘The Last of the Mohicans’ (1992)

“I will find you.” By 1992, Daniel Day-Lewis had proven himself in dramas like The Unbearable Lightness of Being and My Left Foot, but he was still a surprising pick to headline a sweeping frontier romance set during the French and Indian War. Nevertheless, he did a fantastic job in the part. He plays Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe, a colonial-raised frontiersman caught between cultures as imperial powers clash. He finds himself caught in a storm of warfare, survival, and doomed love.

On the directing side, Michael Mann strips away pageantry in favor of physical immediacy, treating landscapes as living forces rather than scenic backdrops. In the process, he achieves an impressive balance between epic scale and human emotion. The action scenes are visceral, the romanticism unguarded, and the sense of loss profound. Fundamentally, the film is a kind of blockbuster fantasy, but one with much more heart than most.

6

‘Glengarry Glen Ross’ (1992)

“Always be closing.” Glengarry Glen Ross takes place almost entirely in offices and restaurants, yet it feels as brutal as any battlefield. The plot revolves around desperate real estate salesmen pushed to compete for their jobs through manipulation, humiliation, and moral compromise. Based on David Mamet’s play, the film is driven by language: profane, rhythmic, and razor-sharp. The stars, including Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alec Baldwin, and Alan Arkin, deliver the barbed dialogue with clear relish. The “Always be closing” monologue, in particular, has become iconic for a reason.

Most of these characters posture at power, but every one of them is trapped in a system that rewards cruelty and punishes hesitation. Indeed, this movie is an unsparing portrait of the worst of capitalism. The anxieties it captures (precarious work, hollow motivation, performative masculinity) feel even more relevant today. Despite (because of?) all this, the movie was a box office disappointment, yet has since become a cult classic.

5

‘Batman Returns’ (1992)

“I’m Catwoman. Hear me roar.” Batman Returns is a studio blockbuster that feels profoundly personal and strangely melancholy. The plot pits Batman (Michael Keaton) against two grotesque figures: a vengeful outcast (Danny DeVito) raised in the sewers and a woman (Michelle Pfeiffer) reborn through trauma. The visuals reflect this bleak mood. Gotham itself becomes a warped reflection of repression and spectacle. Building on the foundation laid by the 1989 movie, Tim Burton transforms the superhero genre into a gothic fairy tale about alienation and desire.

Indeed, heroes and villains alike are driven by loneliness and obsession to the point that good and evil are not always so easy to separate. This approach was bold and innovative for the time, paving the way for countless dark superhero films to follow (not least Christopher Nolan‘s Batman trilogy). Over time, the film has been reappraised as one of the most idiosyncratic big-budget movies ever released by a major studio. Its darkness, once controversial, now feels daring.

4

‘Bram Stoker’s Dracula’ (1992)

“I have crossed oceans of time to find you.” With this movie, Francis Ford Coppola reimagined Dracula as a baroque tragedy, an ambitious undertaking that he (mostly) pulls off. The story follows Dracula’s (Gary Oldman) arrival in Victorian England, setting the stage for a battle between ancient desire and modern rationality. While some aspects, like Keanu Reeves‘ accent, caught a lot of flak, the film’s atmosphere and visual grandeur are worthy of praise. The whole thing is unapologetically excessive.

Coppola embraces theatricality, practical effects, and operatic emotion, rejecting realism in favor of sensation. The film knows exactly what it is and commits fully, swinging for the fences with a big, gothic spectacle. Some viewers will find that simply too over the top and overwrought, but others will appreciate the craft and commitment. The movie also deserves props for deviating from Dracula tropes, particularly with the count’s look and clothing.

3

‘Malcolm X’ (1992)

“By any means necessary.” Denzel Washington received an Oscar nomination for his towering performance in this biopic from Spike Lee. He plays the civil rights leader from troubled youth to global revolutionary figure, convincingly portraying his transformation through crime, faith, activism, and political awakening. At the time, Washington was most well-known for playing calm heroes, so it was striking for audiences to see him getting fiery and full of anger.

The result is a complex, challenging epic, clocking in at well over three hours long. Crucially, Lee refuses simplification, presenting Malcolm as evolving rather than fixed. He treats history as contested, shaped by ideology, betrayal, and reinvention. Simply put, this is one of the most ambitious American biographies ever made. By leaning into the messiness and contradiction of its subject, Malcolm X also becomes a fascinating study of the era and society that the man both grappled with and shaped.

2

‘A Few Good Men’ (1992)

“You can’t handle the truth!” A Few Good Men capped off Rob Reiner‘s remarkable run of movies from the late ’80s into the early ’90s, a streak that gave us classics like Stand By Me and The Princess Bride. This one is a legal drama built around a military trial investigating the death of a Marine (Michael DeLorenzo) following an unofficial disciplinary order. While the movie runs on legal thriller mechanics, its real interest lies in institutional loyalty and moral evasion. The courtroom becomes a stage where authority is performed rather than questioned.

In particular, the movie understands how systems protect themselves by outsourcing blame. The dialogue is sharp, the conflicts legible, and the ethical stakes unmistakable. The legal drama has been around for so long and has been explored so well that it’s difficult to find something new and interesting to say in it, but A Few Good Men managed to put its own distinctive stamp on the genre, one that still holds up today.

1

‘Reservoir Dogs’ (1992)

“I’m gonna torture you anyway, regardless.” Reservoir Dogs detonated into cinema like a challenge. The premise is deceptively simple: a robbery goes wrong and trust unravels among the criminals involved. However, that seemingly straightforward setup is elevated by bold, energetic storytelling, firing on multiple cylinders at once. Quentin Tarantino fractures time, foregrounds dialogue, and treats genre as language rather than formula, weaving in film references and allusions with total confidence. This is one of the most assured directorial debuts of all time.

In 1992, Reservoir Dogs announced a new sensibility, one where pop culture, brutality, and wit coexist without hierarchy. Every scene is calibrated for maximum tension, every line is memorable, and the use of music is ironic yet still deeply entertaining. In other words, all of QT’s hallmarks were here in microcosm, hinting at the more complex masterpieces he would deliver in the decades to follow.

- Release Date

-

September 2, 1992

- Runtime

-

99 minutes

-

Mr. White / Larry Dimmick

-

Mr. Orange / Freddy Newandyke

-

Michael Madsen

Mr. Blonde / Vic Vega

-

Chris Penn

“Nice Guy” Eddie Cabot

Entertainment

CBS pulls “60 Minutes” episode slated to rerun during Super Bowl after new contributor Peter Attia is named in Epstein files

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/Peter-Attia-01-020326-033b0d4e1b4443b28639c4a21802ce83.jpg)

The longevity influencer has apologized for his correspondence with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, but said he “never witnessed illegal behavior.”

Entertainment

A Major Romantic Reveal for Faith Leads to an Even More Intense Plot Twist

Editor’s Note: The following contains spoilers for Will Trent Season 4, Episode 5.

This week’s episode of Will Trent, Season 4, Episode 5, “Nice to Meet You, Malcolm,” switches things up by putting Faith (Iantha Richardson) front and center instead of Will (Ramón Rodríguez). While investigating the murder of a matchmaker, Faith expresses her recent cynicism due to a string of bad dates, only to then meet her dream guy.

“Nice to Meet You, Malcolm,” balances between Faith’s whirlwind romance and its two major cases, as well as a hilarious subplot of Heller (Todd Allen Durkin) and Franklin (Kevin Daniels) building a stroller for Angie’s (Erika Christensen) baby, before ending on a wild cliffhanger. The episode is a fun and intense installment that sets up some really exciting storylines to come, both in terms of a major case, as well as regarding some ongoing character-centered storylines.

In ‘Will Trent’ Season 4, Episode 5, The GBI Investigates the Murder of a Matchmaker

This week, the GBI investigates the murder of a professional matchmaker named Sawyer Jennings, who ran a business called Jennings Luxury. In the hours before Sawyer was killed, he called his business partner, Liv Somerman (Marguerite Moreau), several times. Faith brings Liv in for questioning, but Liv tells her that she and Sawyer had a good partnership and that the business was doing well. The investigation then takes Will and Faith to Anna Martello (Greyson Chadwick), a matchmaking client who’d met with Sawyer at a diner the night he was killed.

Anna tells Will and Faith that she’d recently been matched with a wealthy man named Brody Evans (Logan Michael Smith). Brody drugged and sexually assaulted Anna, and she told Sawyer, who’d confronted him and had planned to expose him. Brody has an alibi for the time that Sawyer was killed, and Will and Faith realize that Liv killed him. Brody wired Liv $100,000 to keep Sawyer from exposing him, so she killed her own business partner. Liv had gone to a lot of trouble to craft a fake alibi, but thanks to a street camera, Will and Faith are able to prove that she’s guilty.

In ‘Will Trent’ Season 4, Episode 5, The APD Investigates a Bank Robbery That Is More Than Meets the Eye

While the GBI looks into Sawyer’s murder, the APD investigates a bank robbery where one person was killed. The only evidence they have are photos of the robbers wearing animal masks, as well as a tattoo on the arm of someone wearing a cheetah mask. Ormewood (Jake McLaughlin) is now done with chemo, and this is his first case since returning to the field. He feels good – almost too good as he notices that his vision is better than it was before his tumor, and his senses are heightened.

The investigation into the tattoo takes Angie and Ormewood to one family, but they’re unable to narrow it down to one of the ten siblings. During the investigation, they have an elevator run-in with Faith and Will. It’s mostly pleasant, but Will doesn’t know how to be around Angie now, even though he’s still been chatting with Ava (Julia Chan). A hurt Will leaves the elevator while Faith and Angie are talking about the baby. Later, Angie and Ormewood finally find the owner of the bank vault, a man named Wyatt Fernsby (Marc Levasseur). Wyatt is attempting to end his life when they find him, but Angie and Ormewood save him.

Wyatt reveals that he works for Biosentia Pharmaceuticals. The company made him shred documents for work, but he kept a copy in his safe deposit box. Someone from the company found out that he had the copy, so they stole it. Afraid of what his former company would do to him, Wyatt tried to end his life. It’s not yet revealed what is in the documents, but it’s bad enough that Wyatt won’t speak about them without a lawyer present. The case is much more than a bank robbery – it was a company trying to hide its illegal activities by hiring an accomplished team of robbers to steal the evidence for them. Because of this, Angie and Ormewood then take this case to the GBI.

‘Will Trent’ Season 4, Episode 5 Gives Faith a New Love Interest – and Delivers a Shocking Twist

Faith goes to a hotel bar for a date with a guy she met on an app, but he gives her the ick before he even gets there. Faith cancels the date, but she is soon swept off her feet by a charming stranger named Malcolm (DeVaughn Nixon). Faith and Malcolm have the perfect night together. The only problem is, she gave him a fake name and job when they first met, and this lie could end up ruining everything between them. Malcolm just gets better the more Faith learns about him. He’s the wealthy owner of the hotel where they met, and he’s enamored with Faith.

Three dates in, things are looking promising for Faith and Malcolm. He puts in a lot of effort and money to make her feel special, and he remembers the little things that she tells him. For a while, it looks like Faith’s lie will be the thing to make this romance collapse. There’s also another exciting obstacle that this episode sets up. In the elevator, Ormewood teases Faith about spending two nights in a row away from home, but there’s a hint of something else beneath his teasing. Sure enough, while on a stakeout with Will, Ormewood and Will have a surprisingly deep talk. Will suggests that Ormewood’s heightened senses are his way of rediscovering who he is after his body failed him. The two joke about Faith’s new romance, but when Will says offhandedly that Faith is happy, Ormewood looks heartbroken when he asks, “She seem happy to you?”

This stakeout scene has two major reveals. Ormewood’s feelings for Faith seem pretty clear at this point, though not outright stated, but they’re not a surprise. This potential romance has been developing since they moved in together last season, and it makes perfect sense. The second reveal of this scene is a major twist. Ormewood found the robber who wore the cheetah mask with the unique tattoo. While investigating this person, Will and Ormewood learn that the robber is Malcolm, and that Faith is with him at that very moment. Will calls Faith to warn her, and the episode ends there, with Faith now having to find a way to keep from blowing her cover, while dealing with this devastating news.

Will Trent airs Tuesdays at 8:00 P.M. EST on ABC.

- Release Date

-

January 3, 2023

- Directors

-

Howard Deutch, Eric Dean Seaton, Holly Dale, Lea Thompson, Patricia Cardoso, Sheree Folkson, Bille Woodruff, Erika Christensen, Gail Mancuso, Geary McLeod, Jason Ensler, Mark Tonderai, Paul McGuigan

- Writers

-

Inda Craig-Galván, Henry ‘Hank’ Jones, Karine Rosenthal, Adam Toltzis, Antoine Perry

-

Ramón Rodríguez

Will Trent

-

Erika Christensen

Angie Polaski

- This episode sets up a compelling case for both the GBI and the AD, with a major plot twist regarding the central suspect.

- This episode centers the characters and their individual conflicts, delivering some important moments for its best dynamics.

Entertainment

Senator Mitch McConnell, 83, Hospitalized With Flu-Like Symptoms

Kentucky Senator Mitch McConnell was admitted into the hospital after suffering “flu-like symptoms” over the weekend.

According to a statement provided to People by a representative for McConnell, 83, on Tuesday, February 3, the longest serving Senate party leader in U.S. history checked himself into a hospital one day prior.

“In an abundance of caution, after experiencing flu-like symptoms over the weekend, Senator McConnell checked himself into a local hospital for evaluation last night,” the statement read.

The Kentucky Republican’s statement also noted that his prognosis is “positive” and he is receiving “excellent care.”

It concluded, “He is in regular contact with his staff and looks forward to returning to Senate business.”

It is unclear how long McConnell is expected to remain in the hospital.

Us Weekly has reached out to a representative for McConnell for comment.

The politician has publicly shared his health issues over the years, while a recent fall that took place in the hallway of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., was witnessed and filmed by reporters.

Shared by local Louisville, Kentucky, news outlet WHAS11, via its YouTube account on October 17, 2025, a video of the incident also captured McConnell walking while assisted by the arm of a colleague just prior to his fall.

The tumble occurred while McConnell was being questioned over his perspective on Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

His Capitol Building fall marked the third public fall of 2025, and the politician has publicly fallen twice in the building in total.

McConnell also suffered a public concussion after tripping and falling inside Washington’s Waldorf Astoria in 2023. His recovery involved reliance on a wheelchair, per reporting at the time by NBC News.

He has also demonstrated public freezing episodes over the years, several of which were captured by news outlets during press conferences. The results of the episodes have left McConnell completely non-responsive in the face of questioning.

McConnell has held the seat of Kentucky since 1985 and is currently in his seventh Senate term. From 2007 to 2025, he also served as the leader of the Senate Republican Conference. He announced last year that he would not seek reelection in 2026.

In 2015, McConnell, who has been married to former government official Elaine Chao since 1993, was first listed as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. He was awarded the same honor in 2019 and 2023.

He is a polio survivor, having endured a polio attack in 1944 when he was two years old. His upper left leg was paralyzed as a result of the attack. Successful treatment from medical staff at the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institution for Rehabilitation at the time, prevented McConnell from developing a permanent disability.

Entertainment

One of the Most Remarkable Movies Ever Made About Space Is Now Available To Watch on Netflix

Space travel has been a subject that has long fascinated filmmakers, as the silent classic A Trip To The Moon was one of the earliest examples of cinema predicting real events. Although the science fiction genre has frequently speculated about the possibilities of space travel, the 1969 NASA lunar mission visualized what it would actually look like, leading to an even greater expansion in imagination. Although it is one of the most important historical moments of its century, the NASA space trip to the lunar surface was not fully realized on film until the 2019 documentary Apollo 11, which assembled previously unseen footage to explore every step of the journey. It’s not only one of the most brilliantly crafted documentaries of the 2010s, but an important work of historical documentation that serves as a reminder of what technological advancements have achieved.

The footage of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the lunar surface is an undeniable part of popular culture, but the technology did not exist to distribute all the footage of the NASA mission in 1969, given the amount of material. It was only after director Todd Douglas Miller and his team of editors spent the time to search through hundreds of hours of both footage and audio experts that they were able to pinpoint the most important material needed to tell the story, all whilst polishing the quality to meet contemporary standards. The result is a documentary that has none of the hallmarks of the medium; Apollo 11 plays so seamlessly that someone with no knowledge of the situation could mistake it for an original piece of dramatic filmmaking.

‘Apollo 11’ Is Edited Like No Other Documentary

Apollo 11 is unique when compared to most documentaries because the film does not include any talking heads, introductory information, narration, or recreations that would break the momentum of the story. What’s being shown is taken from the original film negatives recorded during the original mission, which were only used as a matter of historical record. A majority of these videos were never displayed to the public, giving Apollo 11 the opportunity to blend in unseen aspects of history. The story of the mission itself is so filled with stakes that there was no need to provide any sort of additional drama. It was a sign of bravery on Miller’s part that he trusted the audience to have some degree of awareness of the situation, but it also doesn’t take a scientific expert to enjoy Apollo 11. Even for those who don’t know every step of NASA’s process or understand the different programs that are being cited, Apollo 11 provides a complete portrayal of the many different departments that played a role in the spectacular achievement.

One Of The Year’s Best and Most Overlooked Documentaries Just Landed on Hulu

A film more than worthy of your time.

Seeing the image crystalized in such vivid detail is almost jarring, as the imagery is so crisp that it nearly feels like the film is taking place in real time. Although Apollo 11 obviously did not show every step of the process, as the mission itself was preceded by years of research and testing, the film helps to contextualize the enormity of NASA’s achievement. Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin may have walked away with the most fame, but the scientists who planned the ordeal, the engineers watching the controls, and the journalists who helped to record the event all played a part in pulling off a groundbreaking leap forward for mankind. The focus on showing the team effort is not only an important theme to convey, but an explanation for something that otherwise might seem like science fiction.

‘Apollo 11’ Is an Important Historical Time Capsule

Apollo 11 was given a limited distribution in IMAX theaters, as the scope of the imagery was so detailed that it justified the extended format. Miller was precise in directing the story to show which details would be most important to highlight at given times; even if the process was filled with some slower moments, Apollo 11 is able to navigate between different players involved so that the pacing never came to a halt. There are also components of the film that were left out of most newsroom accounts at the time, including the manner in which NASA prepared for different potential outcomes. It’s easy to forget that the mission could have ended in tragedy, and that there was no guarantee that NASA had both conceived of any possible issues with the mission and properly prepared to deal with them.

Apollo 11 is as detailed of a historical encapsulation as historians could ask for, but it also shows the emotional effect that documentaries can have. No recreation would have the same impact of seeing the real reactions of everyone involved in Apollo 11, as the film does seem to celebrate a grandiose moment that expands beyond any one person, institution, or country. Interestingly, Apollo 11 came only a year after Damien Chazelle’s First Man dramatized Armstrong’s personal journey during the same period; the films serve as perfect companion pieces, as First Man is a creative version of the grounded facts that Apollo 11 brought to life. Nonetheless, Apollo 11 was such a laborious documentary to put together that it feels like an achievement in its own right, and one that benefits all involved. Not only should it serve as an inspiration for those interested in the science of space travel, but as an indication to aspiring filmmakers what the medium may be capable of.

Apollo 11 is now available to stream on Netflix in the U.S.

- Release Date

-

March 1, 2019

- Runtime

-

93 minutes

- Director

-

Todd Douglas Miller

Entertainment

You’re Missing Out on the Best Horror Film To Hit Netflix in a Long Time

To say that the Netflix catalog is a hit-or-miss situation is hardly controversial nowadays. As a matter of fact, the same statement can be made about almost all of our giant, non-curated streaming services. It isn’t that rare for amazing movies and TV shows to pop up on these platforms, but quite often they tend to get buried under piles of titles that range from okay at best to horrifyingly bad. If you’re a horror fan, for instance, you might have missed one of the coolest, scariest, most disturbing films to hit Netflix in quite some time, arguably one of the best to hit our screens this year. After all, to finally come across Luis Javier Henaine’s Disappear Completely, one has to dig deep — almost as deep as the movie’s main character in his search for a cure to the curse that threatens to turn him into a kind of living corpse, a karmic punishment for his own misdeeds as a photojournalist specialized in crime scenes.

After premiering in 2022 at Austin’s Fantastic Fest, Disappear Completely debuted on Netflix in April 2024. And while it made its way to the streamer’s Top 10 in its native Mexico, it has struggled to find an audience in other countries where it is readily available. It’s a pity: Henaine’s film has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and it is indeed a gem that deserves to be seen. Why it has not conquered audiences worldwide is hard to say. Perhaps Netflix hasn’t marketed it enough, or maybe it’s something to do with that pesky one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles. After all, it isn’t rare for international films — particularly genre films — to be overlooked only to be, years later, included in lists of underrated projects.

What Is ‘Disappear Completely’ About?

As it is so new in the world of streaming, Disappear Completely still has a chance of being recognized in its time. The film, which relies more on psychological horror than on traditional jumpscares, is a character study surrounding a man’s relationship with his profession, and his family. The premise is creative and terrifying from the get-go: Santiago (Harold Torres), a photojournalist who sells pictures of crimes and accidents to tabloids, falls victim to a curse after shooting a particularly gruesome scene featuring a still living, but completely unresponsive politician partly devoured by rats. Unbeknownst to him, Santiago’s camera has captured the presence of a demonic entity that traps him in the same web as the senator (Juan Sahagun) he just photographed. Little by little, Santiago starts to lose all of his five senses.

The 25 Best Movies About Missing Persons, Ranked

These crime thrillers go above and beyond to tell their story.

As Santiago races against time to find a cure for his predicament, going from doctors to shamans to the very demon that has hexed him, his girlfriend, Marce (Tete Espinoza), faces troubles of her own. Pregnant with Santiago’s child, she wishes to have the baby and build a happy family. However, Santiago claims that they are not ready to have a child, and pressures her to have an abortion. This relationship with Marce and his unborn baby ends up being essential to how Santiago deals with his curse, being completely responsible for sealing his fate. By the end of the movie, just as he is about to lose the eyesight that is so dear to him, Santiago refuses to deliver his child’s life to the demon in exchange for everything he has lost and therefore becomes forever locked in a tomb made of his own flesh.Mixing an urban vibe with folk horror, Disappear Completely is a movie that dabbles in witchcraft, superstition, and politics, with the cursed senator having been victimized by a political rival. However, the focus of the plot is Santiago himself. The movie asks us to place ourselves in his shoes, forcing us to wonder what it would feel like to be in such a terrifying predicament. The final scenes make this invitation to identify with the main character all the more obvious: as Santiago is losing his sense of hearing, we can barely understand the sounds around him. Eventually, in the blink of an eye, the whole movie goes quiet. As he loses his sight, the image becomes blurry, until it… disappears completely. Seven long, despair-inducing seconds of dark screen stand between the last image of Marce calling Santiago’s name and the film’s end credits.

‘Disappear Completely’s Director Was Intentional About Creating a Personal Film

Director Luis Javier Henaine was intentional in creating an immersive, realistic experience for the audience while filming Disappear Completely, as he shared during an interview with Eye For Film. Rather than relying on jump scares or musical cues, he aimed to “make a more personal film with more down to earth issues,” while still balancing the element of witchcraft and folk horror. He said:

“Here in Mexico, witchcraft is something that people take very seriously and something very, very real for the majority of our population. And I like to reflect that in a way. So, all the time, I was trying to say, ‘Okay, this has to look real, this has to feel real, this has to be very realistic.’ And that’s how I tried to go throughout the whole film, with the production design and with the cinematography and with everything. Our references were real things, how people behave in these environments. . . ”

Placing the audience in Santiago’s shoes is one of the reasons Disappear Completely is so unnerving – it feels personal. At the heart of the film is Santiago’s struggles with being a potential father and a supportive partner for Marce. When reading the script, Henaine envisioned “a very immersive filmmaking style,” one that would make the audience active participants rather than passive observers of Santiago’s slow descent into a tomb of his own flesh. “I thought it would be great to just when, when he starts losing his sense of hearing, just play slowly with the whole film as well, make it subjective, put the audience in the character’s mind,” Henaine explained.

‘Disappear Completely’ Presents Photography as the Ultimate Horror

Disappear Completely presents us with a kind of horror that would be disturbing no matter who it befell. Still, when we take into consideration Santiago’s profession, the film gains additional layers. At the same time that Henaine and his fellow screenwriter Ricardo Aguado-Fentanes ask us to identify with Santiago in his plight, they also make it pretty clear that he is someone we should despise. Santiago is not a tabloid photographer because that’s the only job he can find. On the contrary, he seems to enjoy taking pictures of mangled bodies and even attempts to make it into a form of high art. The movie shows us that he has fun creating tasteless titles for the stories that will accompany his pictures, and right in the beginning we learn that he is trying to sell some of his photos to art galleries. This is, in itself, terrifying: in a way, the biggest horror in Disappear Completely is becoming the subject of one of Santiago’s photographs.

A Susan Sontag quote that opens the movie gives us the key to interpreting the story in this sense. “Photography converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, wittingly or unwittingly, are the angels of death.” In Disappear Completely, a still picture is not just a tomb in a graveyard because it depicts someone who might already be dead, but because having your picture taken is already a kind of death. You become unmoving, unfeeling, blind, and deaf, all at once. You might say something, of course, in the sense that all works of art say something, but you will never again respond to any stimuli.

When he is cursed, Santiago is doomed to become one of his own photographs. His fate is, in a way, an ironic punishment: he has condemned so many dead people to a living death that he will, himself, become a tomb in the cemetery that is the entire world. Disappear Completely is definitely a movie with something to say, and it turns its eyes specifically to the art of creating images. To an extent, it is even fitting to watch Santiago’s downfall happen in a movie instead of, say, reading about it in a book, for the image is essential for us to understand what is happening to him. As we gaze at Santiago, we wonder if what is happening to him might one day happen to us as well. After all, in the age of smart phones and social media platforms where privacy goes to die, haven’t we all produced our own fair share of images that trap people in a single, unchangeable moment?

‘Disappear Completely’ Also Focuses on Santiago’s Relationship with His Unborn Child

But while photography, particularly Santiago’s kind of predatory photojournalism, and its meanings are at the center of Disappear Completely, Henaine and Aguado-Fentanes also go beyond the professional aspect of their protagonist. Well, in a way. Santiago’s relationship with Marce and their unborn child is marked by his career: it is because he hasn’t yet succeeded as a serious photographer that he believes it isn’t yet time for them to have a baby. When confronted with the opportunity to preserve the one sense that he needs for working in exchange for his child, though, Santiago chooses to let himself disappear completely.

Santiago sacrifices himself for his unborn child and, by extension, for the sake of Marce’s happiness. After all, she is the one who wants to have a child. But will Marce still want that baby now that her life has been upended so completely, now that she doesn’t have Santiago by her side anymore? What he does is completely remove himself from Marce’s life, thus leaving her alone to make a decision about her pregnancy and deal with the consequences. It is a selfish choice, but the reality is that there is no decision that Santiago could make that would not be selfish, as trading his baby’s life for his senses would prove tragic for both him and Marce. Either way, the demon forces Santiago to wallow in the selfishness that has ruined his life.

Disappear Completely ultimately wraps up with a fitting conclusion for Santiago. In his infinite suffering, he decides that the world would be a better place without him, for there is no answer that would satisfyingly end his suffering. He has already done too much to be forgiven. He’s already drowned in hubris, having been a man who mocked the death of others and who refused the happiness of the woman who lived with him. He turns the world into a cemetery and thus deserves to be buried alive. Is it a sad conclusion? You bet it is. But, quite often, the best horror stories have a tinge of tragedy to them.

‘Disappear Completely’ Is One of the Best Horror Movies to Hit Our Screens in 2024

With all of that in mind, it is no stretch to call Disappear Completely one of the best horror movies of 2024, despite having started its festival run all the way back in 2022. After all, what counts is when a movie is made available to general audiences, and, even in Mexico, Disappear Completely only managed to get itself a proper theatrical release in February of this year. And, well, considering how divisive the year has been for its horror releases, to watch a movie that isn’t particularly revolutionary, but that does the basics so well can feel like a breath of fresh air. Sure, movies like Longlegs and The Substance have won over hearts and minds all around the world, but they have garnered equally large legions of detractors. As for Disappear Completely; well, it’s not the kind of film that will change your conceptions about what horror can be, but it will definitely scare you and make you think about the themes being laid out on screen.

This should by no means be construed as negative criticism of the film. Simple and straightforward doesn’t mean mediocre. You don’t have to purport to change the genre to create something truly sublime. Sure, a The Bear-like meal at a Michelin-starred restaurant might be life-changing, but a good, old bowl of mac ‘n cheese can be just as tasty and satisfying. From Huesera: The Bone Woman to When Evil Lurks, Latin America has been producing some incredible horror films over this past decade, many of which are available on Prime Video, Netflix, and other streaming services. Thus, why stop at one amazing work of art? After you finish this beautiful, tragic, and terrifying film, take a few days to expand your spooky horizons. Results may vary, of course, but you certainly won’t regret such a rich meal.

- Release Date

-

February 29, 2024

- Runtime

-

106 Minutes

- Director

-

Luis Javier Henaine

- Writers

-

Ricardo Aguado-Fentanes, Luis Javier Henaine

Entertainment

Sherri Shepherd’s Daytime Time Talk Show Cancelled

Sherri Shepherd’s time as a daytime talk show host has officially come to an end. It was recently announced that her self-titled show “Sherri” has been cancelled after four seasons.

The news comes on the heels of another daytime talk show confirming the end of its run, as “The Kelly Clarkson Show” will also not return for additional seasons.

Article continues below advertisement

‘Sherri’ To End This Fall After Four Seasons

Per Variety, “Sherri” has been cancelled and will not continue following the conclusion of its current season, set to wrap up in the fall. Debmar-Mercury, which distributes the show through producer Lionsgate, issued a statement confirming the news.

“This decision is driven by the evolving daytime television landscape and does not reflect on the strength of the show, its production – which has found strong creative momentum this season – or the incredibly talented Sherri Shepherd,” Debmar-Mercury co-presidents Ira Bernstein and Mort Marcus via joint statement.

“We believe in this show and in Sherri and intend to explore alternatives for it on other platforms,” the statement continued.

Article continues below advertisement

” Sherri” premiered in fall 2022, initially taking over the time slot of the long-running “Wendy Williams Show,” which ended after 13 seasons due to the ongoing health and personal issues of the former talk show host.

Article continues below advertisement

Shepherd Previously Expressed Her Happiness About ‘Sherri’ Being Renewed

In March 2025, it was announced that “Sherri” had been renewed for a fourth season, and at the time, Shepherd shared her happiness at continuing.

“I don’t take it for granted that people welcome me into their homes daily,” Shepherd said, per Variety.

“I work so hard to bring escapism to viewers’ lives through joy, laughter, and inspiration, and I’m grateful that the audience has embraced what we do. I look forward to raising the bar and turning up the volume as we plan for our season four return,” she continued.

Article continues below advertisement

Sherri Shepherd Joins Kelly Clarkson As A Now-Former Talk Show Host

Speculation circulated for weeks that “The Kelly Clarkson Show” would end its seven-season run this year, and the news was confirmed on Monday, February 2.

According to Deadline, Clarkson’s contract was up at the end of the show’s current season. However, the recent personal issues she is dealing with are believed to have been the determining factor in her decision not to continue the show.

Last year, Clarkson’s ex-husband and the father of her children, Brandon Blackstock, died due to cancer in August 2025.

Clarkson issued a heartfelt goodbye via an official statement.

Article continues below advertisement

“There have been so many amazing moments and shows over these seven seasons. I am forever grateful and honored to have worked alongside the greatest band and crew you could hope for, all the talent and inspiring people who have shared their time and lives with us, all the fans who have supported our show, and to NBC,” her statement read in part.

“Because of all of that, this was not an easy decision, but this season will be my last hosting ‘The Kelly Clarkson Show.’ Stepping away from the daily schedule will allow me to prioritize my kids, which feels necessary and right for this next chapter of our lives,” Clarkson continued.

The singer ended her message, adding, “I want to thank y’all so much for allowing our show to be a part of your lives, and for believing in us and hanging with us for seven incredible years.”

Article continues below advertisement

Daytime Talk Show Ratings Are Down Across The Board

Although “The View” continues to maintain its long-standing number one ranking, daytime talk show ratings overall have continued a steep decline throughout the years, despite talk shows being led by big names such as Jennifer Hudson, Drew Barrymore, Tamron Hall, and the aforementioned Shepherd and Clarkson.

Per The Hollywood Reporter, “the marketplace for daytime talk shows (and frankly, TV talk shows in general) has deteriorated in recent years amid pay-TV declines, a challenging advertising environment and fierce competition from video podcasts on platforms like YouTube.”

Sherri Shepherd Has Other Things To Fall Back On

Before she entered the world of daytime TV courtesy of “The View,” she had a long career as a comedian and actress. Her prior path in Hollywood would be the most obvious way to continue her career.

Shepherd starred in a variety of television and film projects during both of her talk show stints, something she will likely continue now that “Sherri” has come to an end.

Entertainment

Lisa Rinna 'knew nothing' about Colton Underwood's past during “The Traitors”: 'He got what he asked for'

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/Lisa-Rinna-the-traitors426-020326-ab0225abf0974053b7e7038f9d0dc2a0.jpg)

“Listen, if you ask me to be a Housewife, I’m going to come at you however I’m going to come at you,” the “Real Housewives” alum tells EW.

Entertainment

Apple TV Doubles Down on Sci-Fi With Captivating 2026 Announcement

Apple TV has just blessed us with its 2026 slate — at least for the first half of the year — and it looks like we’ll be watching every minute of the day going by the boatload of prestige TV they just dropped, as the streamer plans to roll out new originals nearly every single week, mixing prestige drama, buzzy thrillers, returning fan favorites and limited series with big stars dipping their toes in the episodic water.

The big headline, of course, is the return of Ted Lasso for Season 4, but that’s just one piece of a lineup that also includes fresh seasons of Shrinking, For All Mankind, Sugar, and more. Add in new shows led by Elisabeth Moss, Kerry Washington, Amy Adams, Javier Bardem, and Anya Taylor-Joy, and Apple is clearly aiming for a “prestige TV every month” vibe. The full year’s breakdown of today’s announced series can be found below.

Apple TV’s 2026 Series Release Schedule

Ted Lasso is back — but with a twist. Season 4 sees Ted coaching a second-division women’s football team, which feels like exactly the kind of heart-forward, underdog energy the show thrives on. And of course, it’s Apple, the home of prestige science fiction, which can only mean one thing: sci-fi fans are eating well. For All Mankind keeps pushing deeper into space in Season 5, while Monarch: Legacy of Monsters expands the MonsterVerse with more Titan chaos. For the crime enthusiasts, prestige thrillers are everywhere. Imperfect Women (Elisabeth Moss, Kerry Washington), Cape Fear (Amy Adams, Javier Bardem), and Criminal Record Season 2 all lean into darker, character-driven mysteries.

And of course, don’t forget about the giggles too, because between Shrinking, Margo’s Got Money Troubles, and the very chaotic-sounding Maximum Pleasure Guaranteed, Apple is still delivering the laughs as regularly as the dystopia.

|

Series Title |

Season |

Premiere Date |

|---|---|---|

|

Shrinking |

Season 3 |

Now Streaming (2026) |

|

The Last Thing He Told Me |

Season 2 |

February 20, 2026 |

|

Season 2 |

February 27, 2026 |

|

|

Imperfect Women |

Limited Series |

March 18, 2026 |

|

Season 5 |

March 27, 2026 |

|

|

Your Friends & Neighbors |

Season 2 |

April 3, 2026 |

|

Margo’s Got Money Troubles |

Season 1 |

April 15, 2026 |

|

Criminal Record |

Season 2 |

April 22, 2026 |

|

Widow’s Bay |

Season 1 |

April 29, 2026 |

|

Maximum Pleasure Guaranteed |

Season 1 |

May 20, 2026 |

|

Cape Fear |

Season 1 |

June 5, 2026 |

|

Season 2 |

June 19, 2026 |

|

|

Lucky |

Limited Series |

July 15, 2026 |

|

Ted Lasso |

Season 4 |

Summer 2026 |

What Movies Are Coming to Apple TV in 2026?

Apple TV has also revealed an impressive lineup of films coming to the streamer this year, from Elizabeth Olsen‘s afterlife romance Eternity, premiering next weekend, and Ryan Reynolds‘ long-awaited Cold War movie coming this fall, to Keanu Reeves‘ latest comedy Outcome and John Cena‘s hotly anticipated Matchbox movie. See the streamer’s full movie slate below.

|

Movie Title |

Starring |

Release Date |

|---|---|---|

|

Eternity |

Elizabeth Olsen, Miles Teller, and Callum Turner |

February 13, 2026 |

|

Outcome |

Keanu Reeves, Cameron Diaz, and Matt Bomer |

April 10, 2026 |

|

The Dink |

Jake Johnson, Ed Harris, and Mary Steenburgen |

July 24, 2026 |

|

Mayday |

Ryan Reynolds, Kenneth Branagh, and Maria Bakalova |

September 4, 2026 |

|

Matchbox The Movie |

John Cena, Jessica Biel, and Danai Gurira |

October 9, 2026 |

|

Way of the Warrior Kid |

Chris Pratt, Linda Cardellini, and Jude Hill |

November 20, 2026 |

Stay tuned at Collider for more!

- Release Date

-

November 1, 2019

- Network

-

Apple TV

- Directors

-

Sergio Mimica-Gezzan, Andrew Stanton, Meera Menon, Dan Liu, Allen Coulter, Craig Zisk, Dennie Gordon, John Dahl, Lukas Ettlin, Wendey Stanzler, Seth Gordon, Sylvain White, Michael Morris, Maja Vrvilo, Sarah Boyd

- Writers

-

Ronald D. Moore, Matt Wolpert, Ben Nedivi, Bradley Thompson, David Weddle, Nichole Beattie, Joe Menosky

Entertainment

A Gripping Case Brings Morgan and Karadec Closer Than Ever

Editor’s Note: The following contains spoilers for High Potential Season 2, Episode 12.Last week’s episode of High Potential ended with Karadec (Daniel Sunjata) rekindling things with his ex-fiancée, Lucia (Susan Kelechi Watson). Despite supporting Karadec and encouraging him to try again with Lucia, Morgan (Kaitlin Olson) had a sad look on her face as she watched them leave together. This seemed to be a clear set-up for the beginning of a possible feelings realization arc for Morgan, and sure enough, this week’s episode takes this to the next level in the very best way.

This week’s episode sees Major Crimes investigating the murder of the wealthy founder of a wellness company. Meanwhile, Oz (Deniz Akdeniz) tries to get his father’s headstone ready in time for a planned memorial service. This is a strong and fast-paced episode throughout, and it benefits from giving focus to each of the characters, and in particular, giving Oz his first subplot that’s completely separate from a case. Best of all, the case puts Morgan and Karadec in what appears to be a near-death situation, and it brings them closer than ever.

In ‘High Potential’ Season 2, Episode 12, Major Crimes Investigates the Murder of a Man Trying to Live Forever

In Season 2, Episode 12, “The Faust and the Furious,” the Major Crimes team investigates the murder of Gabe Rafferty (Brad Raider), the founder of a wellness-focused technology company called Genegevity. Gabe was stabbed inside his house, but there’s no clear sign that somebody got through his very elaborate security system. Morgan and Karadec speak to Gabe’s assistant, Renata (Lyla Porter-Follows), who reveals that he shared his biodata with her through the Genegevity app. After Renata’s mom died, Gabe became a mentor to her and gave her a job. The goal of the company was to stop the aging process so that people could live forever, which started with the treatments that he was using on himself.

The investigation process takes Major Crimes to a number of people who would have had the motivation to kill Gabe. A woman named Siobhan McBriar (Hallie Samuels) was suing Gabe because Genegevity changed the ingredients in her vitamins without telling her, which disrupted her birth control and got her pregnant. Later, they learn that Gabe was embezzling money from Genegevity, and that he had cleverly found ways to make all of his employees blame each other for the company’s financial discrepancies. A message from Gabe beyond the grave assures his company that someone will be taking over for him soon if he’s ever killed. It turns out all of this money was going into creating a new robot version of Gabe that had all of his previous memories and knowledge uploaded.

Robot Gabe speaks to Morgan and Karadec and tells them that the Do Not Disturb system in Gabe’s house was adjusted by someone other than Gabe on the night of his death, making it turn on earlier than usual. Robot Gabe also gives them a list of people who had been threatening Gabe, then the robot is shut down and can no longer talk to them. Morgan and Karadec go to see Mika Aster (Brandon Engman), the founder of the tech start-up that created the robots. Gabe bought the company promising to keep Mika on, but then he pushed Mika out. Morgan and Karadec visit Gabe’s house and briefly get stuck in the room where he was killed. They realize that Gabe was locked in when the Do Not Disturb feature was turned on, and that the candles he lit in the room were laced with arsenic, so Gabe stabbed himself to die faster instead of slowly being poisoned.

The killer turns out to be Renata, who teamed up with Micah to kill Gabe, both for their own reasons. While Micah wanted revenge and his company back, Renata felt betrayed and hurt because Genegivity had originally been researching the genes responsible for her mother and sister’s cancer, which she also carries. When Micah went to confront Gabe about taking over his company, Renata learned that all the money for the research had gone into the robots instead. Renata ultimately confesses after Morgan and Karadec confront her, but she stands by what she did.

In ‘High Potential’ Season 2, Episode 12, Oz Tries To Get a Headstone for His Father’s Grave

It was revealed last season that Oz’s father had died the year before. In this episode, Oz’s family tries to have a belated memorial for him, because they’ve been waiting for his headstone to be ready for a long time. A few days before they’re supposed to have the memorial (after it’s already been moved twice), Oz learns that the headstone was never confirmed with the cemetery. Oz goes to see his mom (Jacqueline Antaramian), and she says she used his father’s life insurance money to pay for the headstone. The costs then piled up, and before she knew it, the money was gone, and there was still no headstone.

Oz is angry with his mom, and she has to call Daphne (Javicia Leslie) to check on him because he won’t take her calls after that. Selena (Judy Reyes) then calls Oz in for a meeting, and he tells her that his mom spent $20,000 on a headstone that is now stuck in a shipping facility. Selena says that the funeral home took advantage of Oz’s mom, but Oz blames himself for not being there for her during his grief. Selena relates to Oz by telling him about her mother’s death, then she encourages him to stop being so hard on himself. Selena steps in to call out the funeral home for its predatory practices, and Oz’s mother gets a full refund. Oz’s father’s grave finally gets a headstone, and they have a memorial service for him. Oz gives a touching eulogy where he comes to terms with his grief, and then he calls the Major Crimes team his family.

In ‘High Potential’ Season 2, Episode 12, a Perceived Near-Death Experience Brings Morgan and Karadec Together

Karadec and Lucia are still seeing each other after reconnecting last week, and they’re already getting serious again. The episode shows how Karadec’s job is no longer the obstacle in their relationship, and it seems to hint that Morgan will become a new obstacle. Morgan shows up to Karadec’s apartment to ask for a ride to work, where she sees Lucia. In the car, Morgan asks Karadec about his relationship, and he tells her that he’s happy.

Later, Morgan and Karadec are investigating Gabe’s house, when they get locked in the room where Gabe was killed, and they believe that the room is filled with the poison that killed Gabe. Morgan has a panic attack, terrified that she doesn’t know what to do, and that there is no way out. She tries to do a grounding exercise, but her mind is full of images of the people she loves the most and will lose if they both die there: her three kids and Karadec. Karadec hugs Morgan to calm her down, and then the door opens, and it’s revealed that there was no poison in the room. It’s one of Morgan and Karadec’s best moments yet, because, on this rare occasion where Morgan feels a loss of control, Karadec is the one who’s able to keep her grounded.

When he gets home from work, Karadec has a conversation with Lucia where they talk about their past breakup and start to move forward together. It’s clear that Karadec has learned his lesson from their breakup, but he also already clearly has feelings for Morgan, even if he doesn’t realize it. After Oz’s father’s memorial, Morgan and Karadec talk about what happened. She feels mortified and ashamed about falling apart instead of being able to help out in that situation, but Karadec tells her that they count on each other, and that she would’ve done the same for him. The show then sets up an upcoming breakdown for Karadec. He tells her that at some point he will have a moment like she did, and that he knows that out of everyone in his life, she’ll be the person who will know how to get him through it. The episode makes it clearer than ever that Morgan will be the obstacle in Karadec’s relationship with Lucia this time around, and based on his facial expression after that last conversation, he may know it, too.

High Potential airs Tuesdays at 9:00 P.M. EST on ABC.

- Release Date

-

September 17, 2024

- Showrunner

-

Todd Harthan

- This episode puts Morgan and Karadec in a suspenseful near-death situation, in what is a phenomenal scene, with excellent acting from both Olson and Sunjata.

- This episode gives Oz his first big storyline outside of work, making the ensemble cast feel more balanced.

Entertainment

Deep Space Nine’ Such a Sharp Spin-Off

When Episode 22 of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine Season 7 arrives, the series is four episodes away from closing the figurative book on Star Trek‘s most artistically risky and exquisitely crafted piece of long-form storytelling to date. A major contributor to that success, franchise mainstay Ronald D. Moore, turns his screenwriting pen upon the audacious spin-off two more times during this home stretch — one of them being Episode 22, titled “Tacking into the Wind.”

Unsurprisingly, given Moore’s reputation for detailed worldbuilding and subversive emotional rawness, the episode exemplifies Deep Space Nine at its height: a crackling synergy of riveting sociopolitical weight, elite character growth, and cohesive narrative escalation. And it’s a simple-on-the-surface exchange from this episode, not one of the dozens of bracing quips or eloquent monologues from previous entries, that serves as a masterful microcosm of Deep Space Nine‘s lasting resonance.

Kira Nerys Challenges Damar During a Pivotal ‘Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’ Scene

The Dominion War, Deep Space Nine‘s crowning arc, boxes its exceedingly complex heroes into exceedingly complex internal conflicts. The forever honorable Captain Benjamin Sisko (Avery Brooks) realizes he can accept tarnishing his soul to defeat a ferocious enemy, while Bajoran ambassador Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor) educates her former oppressors in the same guerrilla warfare tactics she once deployed against them as a freedom fighter.

Her Cardassian pupils include Damar (Casey Biggs), a long-time foe turned begrudging ally who recently defected from Cardassia’s alliance with the Dominion. During “Tacking into the Wind,” the Dominion retaliates against Damar by assassinating his wife and son. Stunned into grieving stillness, Damar can’t fathom an empire insidious enough to wage war by thoughtlessly sacrificing “innocent women and children.” He wonders aloud, “What kind of people give those orders?” Kira, while compassionate about two lost lives, quietly responds by slicing him open with a blade of accountability: “Yeah, Damar. What kind of people give those orders?”

This moment wouldn’t carry as much profound significance without Deep Space Nine‘s multi-season interconnectivity. By this point, Kira has healed her mosaic of wounds without relinquishing her rage — nor should she surrender it. Raised during Cardassia’s decades-long occupation of Bajor, she knows firsthand the abject cruelty, the labor camps, the mass murders, the “I was following orders” rationalizations, and how to respond in kind via an insurgency. With immeasurable generational tragedy always humming underneath her skin, with a Cardassian military officer in close quarters, Kira turns both the irrevocable reality of war and Damar’s culpability back upon him.

‘Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’ Strengthens the Franchise’s Optimism by Testing Its Limits

Even though the Kira of Season 7 regrets striking a defenseless former enemy, her searing, point-blank wisdom unravels Damar into an ideological crisis. For many individuals whose proximity to power keeps them insulated from harm, it doesn’t matter when torment and subjugation befalls a stranger; brutality only becomes substantive once it arrives at their own doorstep. Now that Damar’s reeling from an atrocity identical to the ones for which he’s culpable — and now that he shares a sliver of the same pain the Bajorans have experienced countless times over — he recognizes the useless horror of it all.

All Damar can do against Kira’s words is nod in silent, bleak comprehension, then redirect his fury away from her toward the appropriate source. Even a season earlier, it would’ve been impossible to imagine this self-described loyal patriot reconciling with his own sins as well as those of his self-serving, stagnant, imperialist civilization — let alone act upon his realization that the poisonous old ways he once vowed to uphold must be shattered and remade. If the Cardassians keep chasing after conquest and glory, they won’t survive long enough to even attempt to atone for the bloodshed they’ve aided and abetted.

The premise is virtually identical to a highly popular 1983 miniseries.

Deep Space Nine fully realizes the franchise’s potential by expanding Trek’s progressive fundamentals to their breaking point. Like buffing a diamond into shining sharpness, testing the idea of a peaceful future by measuring the cost required to achieve it strengthens Trek’s optimism into a hope that’s more bittersweet, fragile, but worth cherishing all the more. By Deep Space Nine‘s finale, the series’ surviving characters find closure because trial-by-fire reassessments like Damar’s have forced them to abandon their initial prejudices, oversights, or naivety.

Although it’s been a bitter pill to swallow, their adjusted vision for the future doesn’t lack the franchise’s defining idealism; it’s stronger and clearer for acknowledging the cycles of violence and their answering inevitability: righteous resistance against war, corruption, and would-be tyrants. Some manner of change can always happen, however small — and maybe, just maybe, the ultimate change can finally take hold: human nature’s best virtues rising above their worst.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine

- Release Date

-

1993 – 1999-00-00

- Showrunner

-

Michael Piller, Ira Steven Behr

- Writers

-

Rick Berman, Michael Piller

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoSmart energy pays enters the US market, targeting scalable financial infrastructure

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Software stocks enter bear market on AI disruption fear with ServiceNow plunging 10%

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoWhy is the NHS registering babies as ‘theybies’?

-

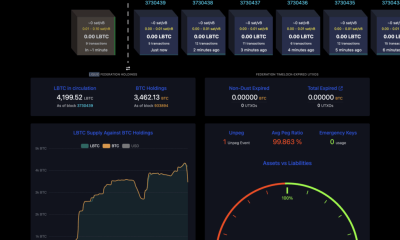

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoAdam Back says Liquid BTC is collateralized after dashboard problem

-

Video1 day ago

Video1 day agoWhen Money Enters #motivation #mindset #selfimprovement

-

Tech3 hours ago

Tech3 hours agoWikipedia volunteers spent years cataloging AI tells. Now there’s a plugin to avoid them.

-

NewsBeat5 days ago

NewsBeat5 days agoDonald Trump Criticises Keir Starmer Over China Discussions

-

Politics2 days ago

Politics2 days agoSky News Presenter Criticises Lord Mandelson As Greedy And Duplicitous

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoU.S. government enters partial shutdown, here’s how it impacts bitcoin and ether

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoSinner battles Australian Open heat to enter last 16, injured Osaka pulls out

-

Fashion5 days ago

Fashion5 days agoWeekend Open Thread – Corporette.com

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoBitcoin Drops Below $80K, But New Buyers are Entering the Market

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoMarket Analysis: GBP/USD Retreats From Highs As EUR/GBP Enters Holding Pattern

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoKuCoin CEO on MiCA, Europe entering new era of compliance

-

Business5 days ago

Entergy declares quarterly dividend of $0.64 per share

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoShannon Birchard enters Canadian curling history with sixth Scotties title

-

NewsBeat1 day ago

NewsBeat1 day agoUS-brokered Russia-Ukraine talks are resuming this week

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoGAME to close all standalone stores in the UK after it enters administration

-

Crypto World12 hours ago

Crypto World12 hours agoRussia’s Largest Bitcoin Miner BitRiver Enters Bankruptcy Proceedings: Report

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoWhy AI Agents Will Replace DeFi Dashboards