The hunt is on for anything that can surmount AI’s perennial memory wall–even quick models are bogged down by the time and energy needed to carry data between processor and memory. Resistive RAM (RRAM)could circumvent the wall by allowing computation to happen in the memory itself. Unfortunately, most types of this nonvolatile memory are too unstable and unwieldy for that purpose.

Fortunately, a potential solution may be at hand. At December’s IEEE International Electron Device Meeting (IEDM), researchers from the University of California, San Diego showed they could run a learning algorithm on an entirely new type of RRAM.

“We actually redesigned RRAM, completely rethinking the way it switches,” says Duygu Kuzum, an electrical engineer at the University of California, San Diego, who led the work.

RRAM stores data as a level of resistance to the flow of current. The key digital operation in a neural network—multiplying arrays of numbers and then summing the results—can be done in analog simply by running current through an array of RRAM cells, connecting their outputs, and measuring the resulting current.

Traditionally, RRAM stores data by creating low-resistance filaments in the higher-resistance surrounds of a dielectric material. Forming these filaments often needs voltages too high for standard CMOS, hindering its integration inside processors. Worse, forming the filaments is a noisy and random process, not ideal for storing data. (Imagine a neural network’s weights randomly drifting. Answers to the same question would change from one day to the next.)

Moreover, most filament-based RRAM cells’ noisy nature means they must be isolated from their surrounding circuits, usually with a selector transistor, which makes 3D stacking difficult.

Limitations like these mean that traditional RRAM isn’t great for computing. In particular, Kuzum says, it’s difficult to use filamentary RRAM for the sort of parallel matrix operations that are crucial for today’s neural networks.

So, the San Diego researchers decided to dispense with the filaments entirely. Instead they developed devices that switch an entire layer from high to low resistance and back again. This format, called “bulk RRAM”, can do away with both the annoying high-voltage filament-forming step and the geometry-limiting selector transistor.

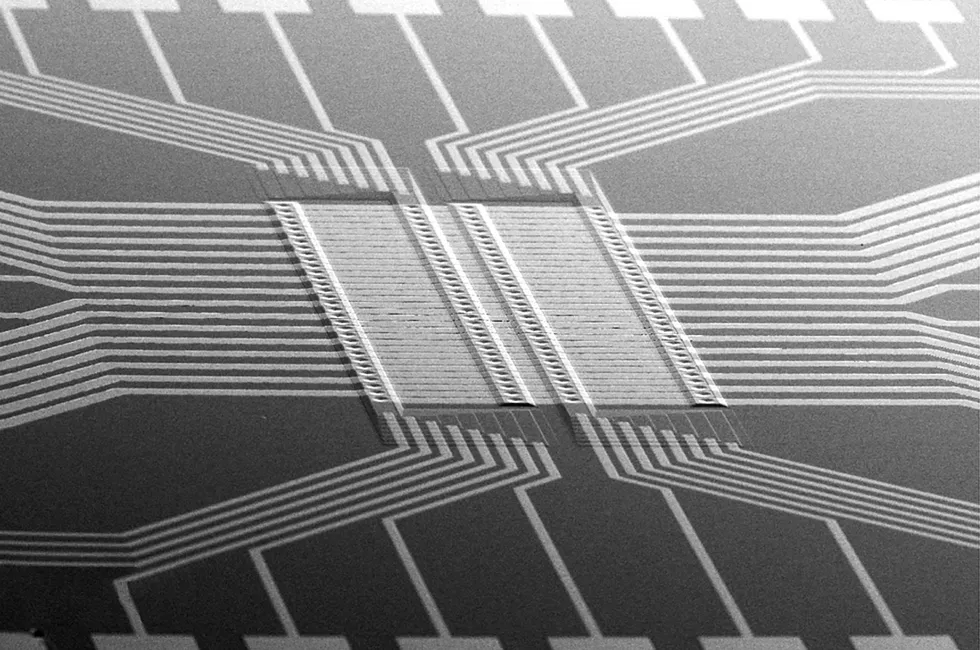

The San Diego group wasn’t the first to build bulk RRAM devices, but it made breakthroughs both in shrinking them and forming 3D circuits with them. Kuzum and her colleagues shrank RRAM into the nanoscale; their device was just 40 nm across. They also managed to stack bulk RRAM into as many as eight layers.

With a single pulse of identical voltage, an eight-layer stack of cells each of which can take any of 64 resistance values, a number that’s very difficult to achieve with traditional filamentous RRAM. And whereas the resistance of most filament-based cells are limited to kiloohms, the San Diego stack is in the megaohm range, which Kuzum says is better for parallel operations. e

“We can actually tune it to anywhere we want, but we think that from an integration and system-level simulations perspective, megaohm is the desirable range,” Kuzum says.

These two benefits–a greater number of resistance levels and a higher resistance–could allow this bulk RRAM stack to perform more complex operations than traditional RRAM’s can manage.

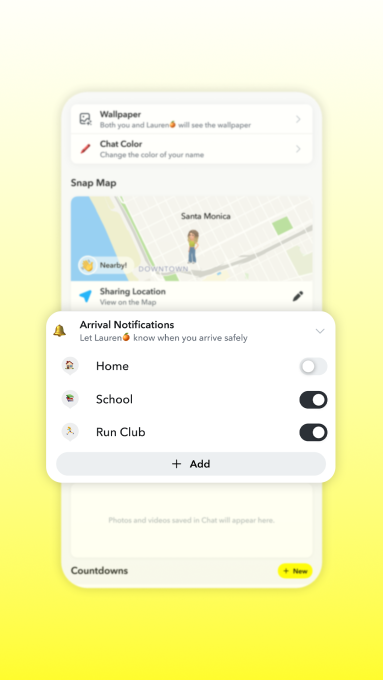

Kuzum and colleagues assembled multiple eight-layer stacks into a 1-kilobyte array that required no selectors. Then, they tested the array with a continual learning algorithm: making the chip classify data from wearable sensors—for example, reading data from a waist-mounted smartphone to determine if its wearer was sitting, walking, climbing stairs, or taking another action—while constantly adding new data. Tests showed an accuracy of 90 percent, which the researchers say is comparable to the performance of a digitally-implemented neural network.

This test exemplifies what Kuzum thinks can especially benefit from bulk RRAM: neural network models on edge devices, which may need to learn from their environment without accessing the cloud.

“We are doing a lot of characterization and material optimization to design a device specifically engineered for AI applications,” Kuzum says.

The ability to integrate RRAM into an array like this is a significant advance, says Albert Talin, materials scientist at Sandia National Laboratories in Livermore, California, and a bulk RRAM researcher who wasn’t involved in the San Diego group’s work. “I think that any step in terms of integration is very useful,” he says.

But Talin highlights a potential obstacle: the ability to retain data for an extended period of time. While the San Diego group showed their RRAM could retain data at room temperature for several years (on par with flash memory), Talin says that its retention at the higher temperatures where computers actually operate is less certain. “That’s one of the major challenges of this technology,” he says, especially when it comes to edge applications.

If engineers can prove the technology, then all types of models may benefit. This memory wall has only grown higher this decade, as traditional memory hasn’t been able to keep up with the ballooning demands of large models. Anything that allows models to operate on the memory itself could be a welcome shortcut.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web