Science & Environment

How unusual has it been?

NASA/ISS

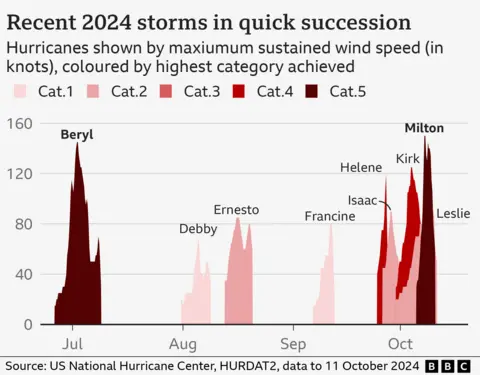

NASA/ISSHurricanes Helene and Milton – which have devastated parts of the south-east United States – have bookended an exceptionally busy period of tropical storms.

In less than two weeks, five hurricanes formed, which is not far off what the Atlantic would typically get in an entire year.

The storms were powerful, gaining strength with rapid speed.

Yet in early September, when hurricane activity is normally at its peak, there were peculiarly few storms.

So, how unusual has this hurricane season been – and what is behind it?

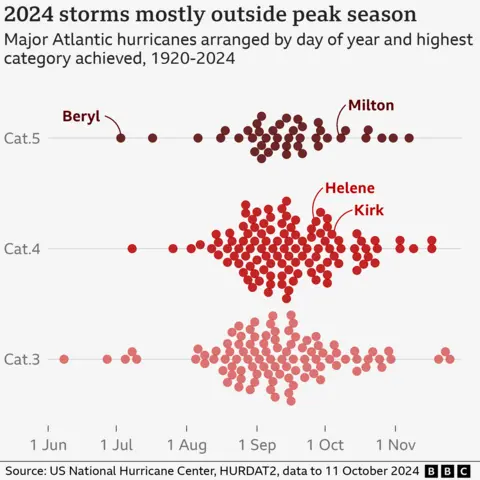

The season started ominously. On 2 July, Hurricane Beryl became the earliest category five hurricane to form in the Atlantic on records going back to 1920.

Just a few weeks earlier in May, US scientists had warned the 2024 season from June to November could be “extraordinary”.

It was thought that exceptionally warm Atlantic temperatures – combined with a shift in regional weather patterns – would make conditions ripe for hurricane formation.

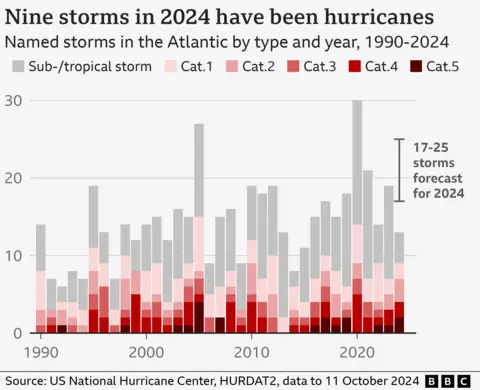

So far, with seven weeks of the official season still to go, there have been nine hurricanes – two more than the Atlantic would typically get.

However, the total number of tropical storms – which includes hurricanes but also weaker storms – has been around average, and less than was expected at the start of the year.

After Beryl weakened, there were only four named storms, and no major hurricanes, until Helene became a tropical storm on 24 September.

That is despite warm waters in the tropical Atlantic, which should favour the growth of these storms.

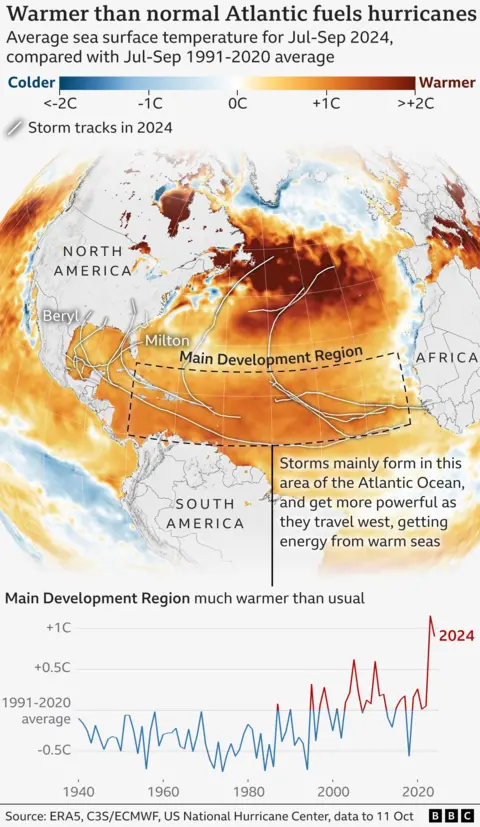

Across the Main Development Region for hurricanes – an area stretching from the west coast of Africa to the Caribbean – sea surface temperatures have been around 1C above the 1991-2020 average, according to BBC analysis of data from the European climate service.

Atlantic temperatures have been higher over the last decade, mainly because of climate change and a natural weather pattern known as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation.

The recipe for hurricane formation involves a complex mix of ingredients beyond sea temperatures, and these other conditions were not right.

“The challenge [for forecasting] is that other factors can change quickly, on the timescale of days to weeks, and can work with or against the influence of sea surface temperatures,” explains Christina Patricola, associate professor at Iowa State University.

Researchers are still working to understand why this was the case, but likely reasons include a shift to the West African monsoon and an abundance of Saharan dust.

These both hampered storm development by creating unfavourable conditions in the atmosphere.

But even during this period, scientists were warning that the oceans remained exceptionally warm and that intense hurricanes were still possible through the rest of the season.

And in late September, they came.

Starting with Helene, six tropical Atlantic storms were born in quick succession.

Fuelled by very warm waters – and now more favourable atmospheric conditions – these storms strengthened, with five becoming hurricanes.

Four of these five underwent what is known as “rapid intensification”, where maximum sustained wind speeds increase by at least 30 knots (35mph; 56km/h) in 24 hours.

Historical data suggests that only around one in four hurricanes rapidly intensify on average.

Rapid intensification can be particularly dangerous, because these quickly increasing wind speeds can give communities less time to prepare for a stronger storm.

Hurricane Milton strengthened by more than 90mph in 24 hours – one of the fastest such cases of intensification ever recorded, according to BBC analysis of data from the National Hurricane Center.

Scientists at the World Weather Attribution group have found that the winds and rain from both Helene and Milton were worsened by climate change.

“One thing this hurricane season is illustrating clearly is that the impacts of climate change are here now,” explains Andra Garner from Rowan University in the US.

“Storms like Beryl, Helene, and Milton all strengthened from fairly weak hurricanes into major hurricanes within 12 hours or less, as they travelled over unnaturally warm ocean waters.”

Milton also took an unusual, although not unprecedented, storm path, tracking eastward through the Gulf of Mexico, where waters have been exceptionally warm.

“It is very rare to see a [category] five hurricane appearing in Gulf of Mexico,” says Xiangbo Feng, research scientist in tropical cyclones at the University of Reading.

Warmer oceans make stronger hurricanes – and rapid intensification – more likely, because it means storms can pick up more energy, potentially leading to higher wind speeds.

What about the rest of the season?

US forecasters are currently watching an area of thunderstorms located over the Cabo Verde Islands off the west coast of Africa.

This could develop into another tropical storm over the next couple of days, but that remains uncertain.

As for the rest of the season, high sea surface temperatures remain conducive for further storms.

There is also the likely development of the natural La Niña weather phenomenon in the Pacific, which often favours Atlantic hurricane formation as it affects wind patterns.

But further activity will rely on other atmospheric conditions remaining favourable, which are not easy to predict.

Either way, this season has already highlighted how warm seas fuelled by climate change are already increasing the chances of the strongest hurricanes – something that is expected to continue as the world warms further.

“Hurricanes occur naturally, and in some parts of the world they are regarded as part of life,” explains Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, USA.

“But human-caused climate change is supercharging them and exacerbating the risk of major damage.”

Science & Environment

WTI, Brent head to small weekly gain

U.S. crude oil on Friday was on pace to eek out its second weekly gain in a row as Israel prepares to retaliate against Iran.

The U.S. benchmark has gained 1% this week, while global benchmark Brent is ahead 0.8%. Oil prices have gained more than 10% through Thursday’s close since Iran hit Israel with ballistic missiles last week.

“Nevertheless, sustaining bullish price momentum in oil has proven to be a high maintenance task: without additional catalysts, the ‘war’ and ‘stimulus’ premiums have shown easy susceptibility to fading,” Natasha Kaneva, head of global commodity strategy at JP Morgan, told clients in a Friday note.

Here are Friday’s energy prices:

- West Texas Intermediate November contract: $75.21 per barrel, down 64 cents, or 0.84%. Year to date, U.S. crude oil has gained nearly 5%.

- Brent December contract: $78.77 per barrel, down 63 cents, or 0.79%. Year to date, the global benchmark has increased about 2%.

- RBOB Gasoline November contract: $2.1414 per gallon, down 0.44%. Year to date, gasoline is ahead 1.7%.

- Natural Gas November contract: $2.685 per gallon, up 0.37%. Year to date, gas has risen about 6%.

Israel’s security cabinet met Thursday to discuss the country’s response to Iran’s attack, according to media reports. President Joe Biden and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke by phone on Wednesday.

Traders have worried that Israel will hit Iran’s oil industry, potentially triggering a cycle of escalation that causes a significant disruption of supplies in the Middle East. Biden has discouraged Israel from targeting Iran’s oilfields. The Arab Gulf states have also reportedly lobbied the White House to pressure Israel to refrain from hitting Iranian energy infrastructure.

“We expect that the White House is potentially encouraging Israel to target refineries instead of oil export facilities, arguing that the economic impact would be more directly felt by Iran,” Helima Croft, head of global commodities strategy at RBC Capital Markets told clients in a Thursday note.

Croft warned, however, that the U.S. influence may have waned since April, when Israel’s response to Iran’s first missile and drone attack was relatively muted.

Science & Environment

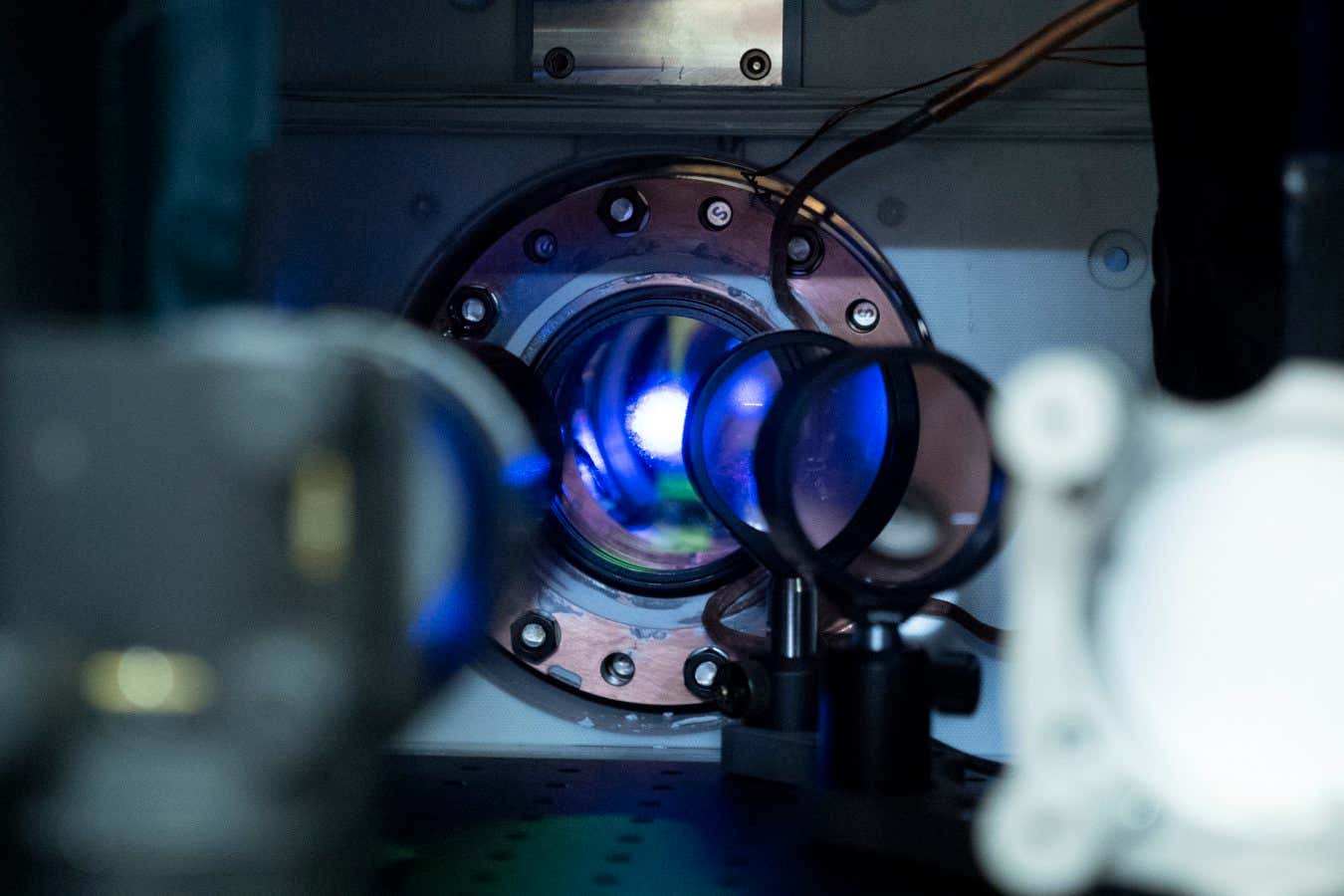

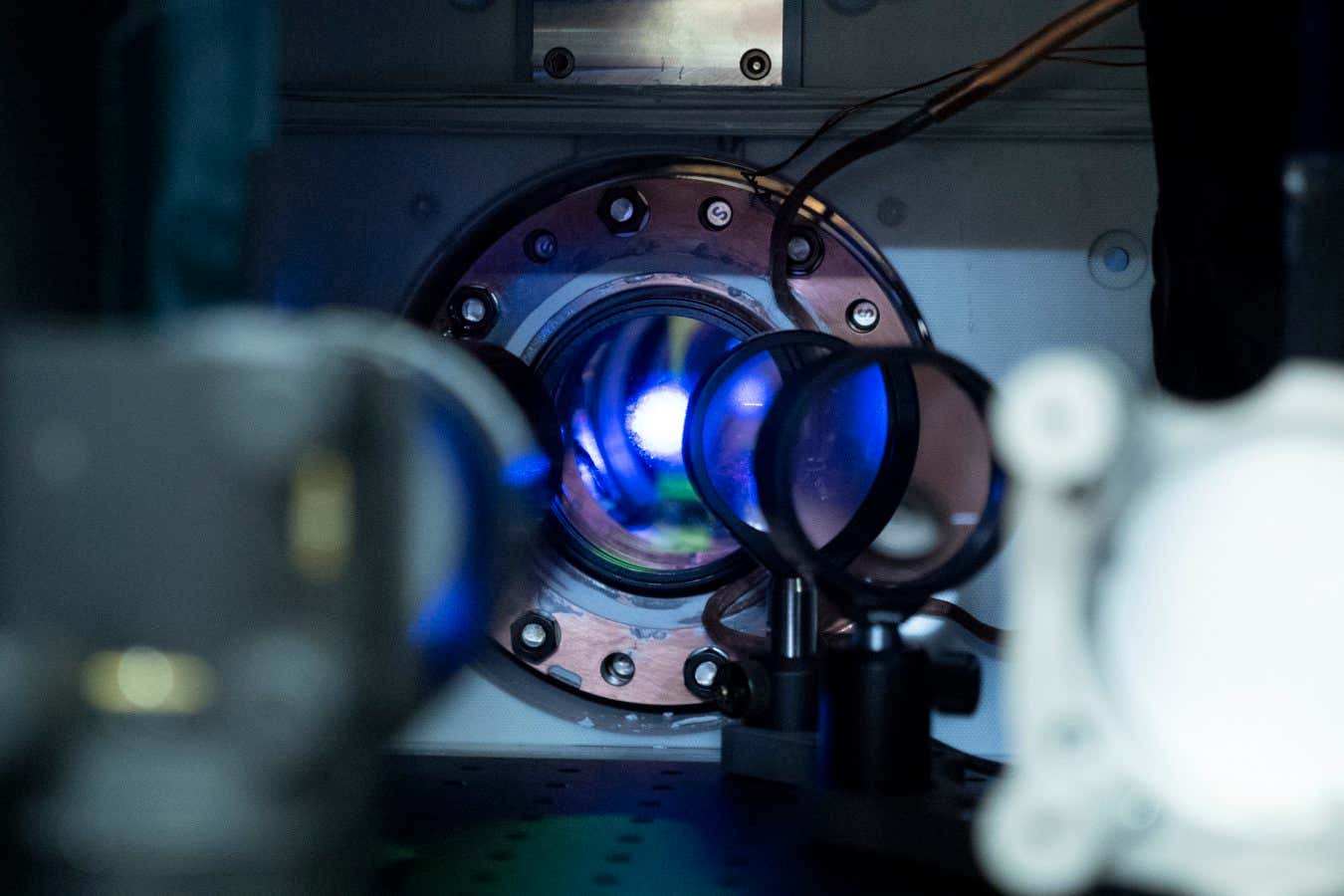

Tiniest ‘ruler’ ever measures distances as small as an atom’s width

This fluorescent technique can precisely measure minuscule distances

Steffen J. Sahl / Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences

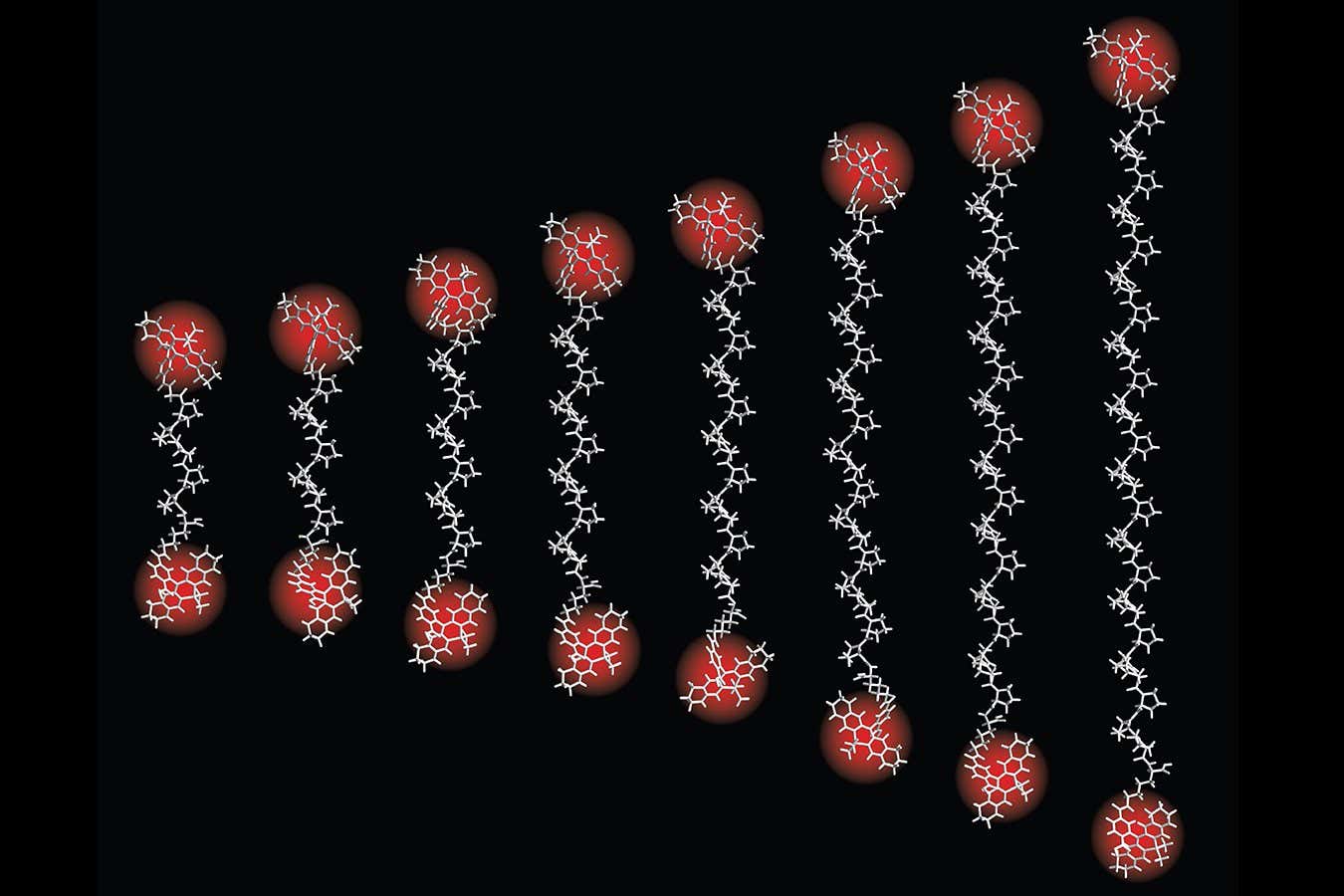

The tiniest “ruler” ever is so precise that it can measure the width of a single atom within a protein.

Proteins and other large molecules, or macromolecules, sometimes fold into the wrong shape, and this can affect the way they function. Some structural changes even play a role in conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. To understand this process, it is important to determine the exact distance between atoms – and clusters of atoms – within these macromolecules, says Steffen Sahl at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences in Germany.

“We wanted to go from a microscope that maps positions of macromolecules relative to each other, to taking this bold step of going within the macromolecule,” he says.

To construct their intramolecular “ruler”, Sahl and his colleagues used fluorescence, or the fact that some molecules glow when illuminated. They attached two fluorescent molecules to two different points on a larger protein molecule and then used a laser beam to illuminate them. Based on the light the glowing molecules released, the researchers could measure the distance between them.

They used this method to measure distances between the molecules of several well-understood proteins. The smallest of those distances was just 0.1 nanometres – the width of a typical atom. The fluorescent ruler also gave accurate measurements up to about 12 nanometres, meaning it had a broader measuring range than can be achieved with many traditional methods.

In one example, the researchers looked at two different forms of the same protein and found that they could distinguish between them because the same two points were 1 nanometre apart for one shape and 4 nanometres apart for the other. In another experiment, they measured tiny distances in a human bone cancer cell.

Sahl says the team achieved this precision by taking advantage of several recent technological advances, like better microscopes and fluorescent molecules that don’t flicker and don’t produce a glow that could be confused with some other effect.

“I don’t know how they got their microscopes so stable. The new technique is definitely a technical advance,” says Jonas Ries at the University of Vienna in Austria. But future studies will have to determine for which exact molecules it will prove most useful as a source of information for biologists, he says.

“While it boasts impressive precision, the new method may not necessarily achieve the same level of detail, or resolution, when applied to more complex biological systems,” says Kirti Prakash at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and Institute of Cancer Research in the UK. Additionally, he says that several other new techniques are already becoming competitive in terms of measuring smaller and smaller distances.

Sahl says his team will now work on two tracks: refining the method further and expanding their ideas about which macromolecules they can now peer inside.

Topics:

Science & Environment

What is Elon Musk’s Starship space vehicle?

Getty Images

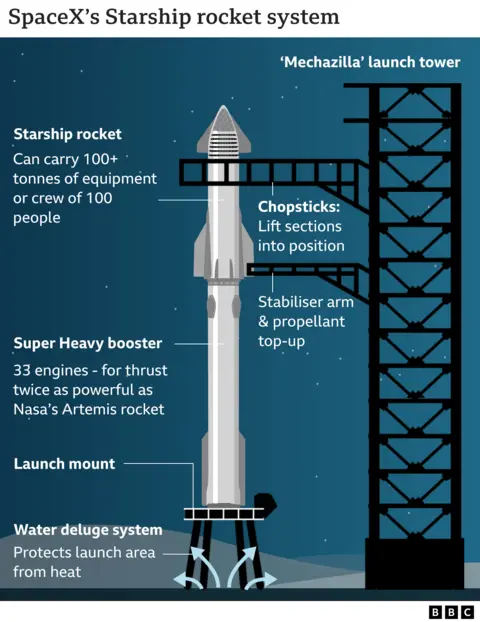

Getty ImagesElon Musk wants his new rocket to revolutionise spaceflight. And that rocket, Starship, is now the largest and most powerful spacecraft ever built.

It’s also designed to be fully and rapidly reusable. His private company SpaceX, which is behind the creation, is hoping to develop a spaceship that can be used more like a plane than a traditional rocket system, being able to land, refuel and take off again a few hours after landing.

When will Starship’s next launch be?

While there’s no exact date set yet for the rocket’s next flight, it could be as soon as this weekend – and SpaceX is expecting big things.

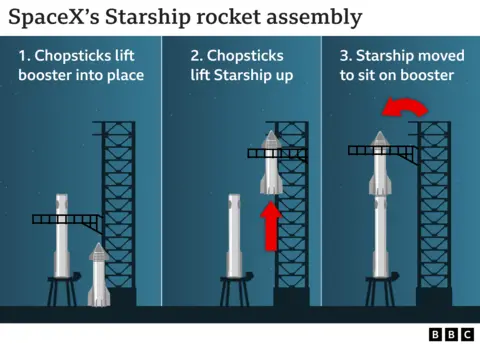

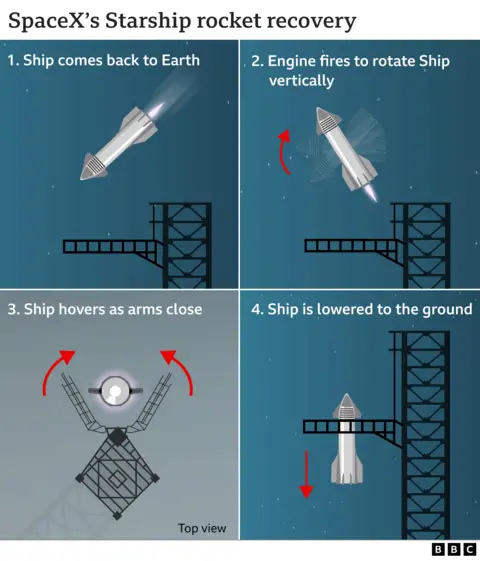

This will be Starship’s fifth outing, and all eyes will be on the landing phases – specifically, the return of the vehicle’s bottom part, the Super Heavy booster.

So far we’ve only seen what might be called a simulated landing at sea, or ‘splashdown’. This will be the first time we hope to see the booster return to the launch pad.

For a spacecraft to be reusable, it needs to be able to land safely.

The SpaceX founder has said they will try to catch the booster in mid-air on its return to Earth using the giant mechanical arms, or ‘chopsticks’, of the launch tower – or as Musk calls it, “Mechazilla”.

That’s something that’s never been done before, and eventually SpaceX want to catch the Ship – the top part of the vehicle – in the same way. But that won’t happen on the upcoming test flight.

Will Starship go to Mars?

None of Starship’s missions so far have been crewed, and there’s no plans to put people aboard for the next flight either.

But Musk and his company do have grand designs that the rocket system will one day take humanity to Mars.

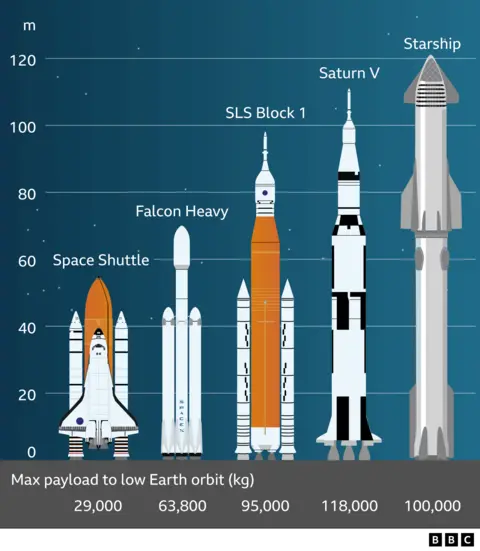

A Mars trip isn’t on the horizon just yet. But the behemoth rocket already has some impressive specs, and dwarfs all of its predecessors.

How big and powerful is Starship?

Starship is a two-stage vehicle. The “Ship” is the uppermost part, and that sits atop a booster called Super Heavy.

Thirty-three engines at the base of this booster produce around 74 meganewtons of thrust. To put that into perspective, it’s almost 700 times as powerful as the thrust generated by the common passenger plane, the Airbus A320neo.

If you’ve flown with Aer Lingus, British Airways or Lufthansa, imagine the kick of taking off in one of those planes. Then multiply that by 700.

The vehicle has grown about a metre since its second test flight in June of this year, with Starship now measuring just over 120m in total.

This additional height comes from the Super Heavy booster itself being made 1m longer.

It’s also about twice as powerful as the Saturn V rocket which first took humanity to the Moon’s surface.

SpaceX says that power should be able to move a payload weighing at least 150 tonnes from the launchpad to low-Earth orbit.

Both the Ship and the Super Heavy booster are fuelled with a mixture of icy-cold liquid methane and liquid oxygen fuel, known as methalox.

What has Starship done so far?

Starship has had four test flights up to now. During the first flight, the rocket system exploded early, before the Booster was able to separate.

It’s worth noting that such hiccups are part of SpaceX’s plan to speed up development by launching systems they know are not perfect and learning from the faults.

And each test has seen real progress – first with a hitch-free separation, and eventually a successful return, where both the Ship and the Booster made a controlled descent and hovered above the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Mexico respectively until splashing down.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHow does Starship land?

SpaceX

SpaceXAnyone watching nearby as the booster returns to Earth can expect a thunderous boom as it slows down from supersonic speeds.

While SpaceX plan to catch the booster with the launch tower, we won’t get a similar return of the top part – the Ship – this time. When we do, it shouldn’t look too different from the Super Heavy’s descent.

But since there’s no launch tower on Mars, or on the Moon for that matter, the Ship also needs to be able to land on its legs.

To do that, it manoeuvres itself horizontally as it starts to descend, in what Musk has called a ‘belly-flop’ manoeuvre. This increases the drag on the vehicle, slowing it down.

SpaceX

SpaceXOnce the Ship gets close enough to the surface, it’s then slow enough to fire its engines in a way that flips the vehicle into a vertical position.

The Ship then uses its rockets to guide itself down safely and land on a hard pad upon its landing legs.

All of this has been done by the Ship on its previous flight – apart from landing on a pad. So far it has only landed in the sea.

What are the challenges?

One of the purposes of test flying is to highlight problem areas, and the quick turnaround between each test flight means that weak links have to be redesigned at lightning speed.

If you get one thing wrong, the entire internal structure of the rocket could be melted by hot gases.

SpaceX

SpaceXWhat else will Starship be used for?

There are a few things Starship could be used for soon.

So far Musk has used his own rockets, like the Falcon 9 series, to launch his own commercial satellites, known as Starlink.

Those satellites have a short lifespan of around five years, and the flock in orbit needs to be constantly replenished just to keep the same number of satellites in space.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNasa also wants to use Starship as part of its Artemis programme, which aims to establish a long-term human presence on the Moon.

NASA

NASAIn the more distant future, Musk wants Starship to make long-haul trips to Mars and back – about a nine month trip each way.

“You could conceivably have five or six people per cabin, if you really wanted to crowd people in. But I think mostly we would expect to see two or three people per cabin, and so nominally about 100 people per flight to Mars,” Musk said.

The idea is to send the Ship part of the vehicle into low-Earth orbit, and “park” it there. It could then be refuelled in orbit by a SpaceX ‘tanker’ – essentially another Ship without the windows – for its onward journey to Mars.

It’s also conceivable that Starship could be used to launch space telescopes.

The Hubble telescope is about the size of a bus, and the James Webb telescope is almost three times as big as that.

To put up thousands of satellites quickly, or a bigger telescope, you need a big rocket.

Finally, Starship has also been built to carry heavy loads needed to build space stations, and eventually, infrastructure for a human presence on the Moon.

How much greenhouse gas does Starship emit?

A rocket that kicks 700 times harder than a passenger jet is bound to have some impact on the environment.

A draft environmental report by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) released in July shows that the new licence SpaceX is applying for would allow them 25 launches of Starship per year.

The FAA say this would emit a total of 97,342 tonnes of CO2 equivalent – or 3,894 tonnes per launch.

In comparison, a typical car in the US emits about 4.6 tonnes of CO2 per year, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency.

If we crunch the numbers, that means one launch of Starship emits as much greenhouse gas as 846 cars would emit over the course of a year.

From a sheer numerical standpoint, that’s fairly insignificant compared to say, the commercial aviation industry.

But with Musk hoping to increase the number of launches to potentially hundreds per year in the future, those numbers could start adding up.

Science & Environment

Wall Street analysts downgrade Honeywell. We think they’re making a mistake.

Honeywell International Inc. signage is displayed on a monitor on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in New York.

Michael Nagle | Bloomberg | Getty Images

Honeywell stock received a rare downgrade from JPMorgan on Thursday. It’s the first time in more than a decade that analysts at the firm lowered their rating.

Science & Environment

Shackleton’s lost ship as never seen before

After more than 100 years hidden in the icy waters of Antarctica, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship Endurance has been revealed in extraordinary 3D detail.

For the first time we can see the vessel, which sank in 1915 and lies 3,000m down at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, as if the murky water has been drained away.

The digital scan, which is made from 25,000 high resolution images, was captured when the ship was found in 2022.

It’s been released as part of a new documentary called Endurance, which will be shown at cinemas.

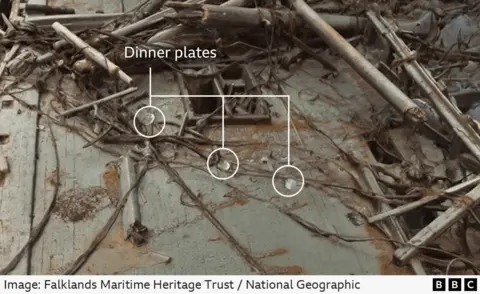

The team has scoured the scan for tiny details, each of which tell a story linking the past to the present.

In the picture below you can see the plates that the crew used for daily meals, left scattered across the deck.

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National Geographic

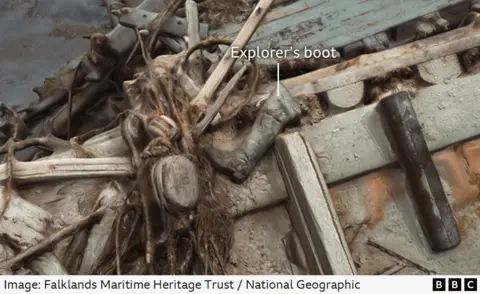

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National GeographicIn the next picture there’s a single boot that might have belonged to Frank Wild, Shackleton’s second-in-command.

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National Geographic

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National GeographicPerhaps most extraordinary of all is a flare gun that’s referenced in the journals the crew kept.

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National Geographic

Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust / National GeographicThe flare gun was fired by Frank Hurley, the expedition’s photographer, as the ship that had been the crew’s home was lost to the ice.

“Hurley gets this flare gun, and he fires the flare gun into the air with a massive detonator as a tribute to the ship,” explains Dr John Shears who led the expedition that found Endurance.

“And then in the diary, he talks about putting it down on the deck. And there we are. We come back over 100 years later, and there’s that flare gun, incredible.”

A doomed mission

Sir Ernest Shackleton was an Anglo-Irish explorer who led the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, which set out to make the first land crossing of Antarctica.

But the mission was doomed from the outset.

Endurance became stuck in pack ice within weeks of setting off from South Georgia.

The ship, with the crew on board, drifted for months before the order was eventually given to abandon ship. Endurance finally sank on 21 November 1915.

Shackleton and his men were forced to travel for hundreds of miles over ice, land and sea to reach safety – miraculously all 27 of the crew survived.

Their extraordinary story was recorded in their diaries, as well as in Frank Hurley’s photographs, which have had colour added for the Endurance documentary.

BFI/Frank Hurley

BFI/Frank HurleyThe ship itself remained lost until 2022.

Its discovery made headlines around the world – and the footage of Endurance revealed that it is beautifully preserved by the icy waters.

The new 3D scan was made using underwater robots that mapped the wreck from every angle, taking thousands of photographs. These were then “stitched” together to create a digital twin.

While footage filmed at this depth can only show parts of Endurance in the gloom, the scan shows the complete 44m long wooden wreck from bow to stern – even recording the grooves carved into the sediment as the ship skidded to a halt on the seafloor.

The model reveals how the ship was crushed by the ice – the masts toppled and parts of the deck in tatters – but the structure itself is largely intact.

Shackleton’s descendants say Endurance will never be raised – and its location in one of the most remote parts of the globe means visiting the wreck again would be extremely challenging.

But Nico Vincent from Deep Ocean Search, who developed the technology for the scans, along with Voyis Imaging and McGill University, said the digital replica offers a new way to study the ship.

“It’s absolutely fabulous. The wreck is almost intact like she sank yesterday,” said Mr Vincent, who was also a co-leader for the expedition.

He said the scan could be used by scientists to study the sea life that has colonised the wreck, to analyse the geology of the sea floor, and to discover new artefacts.

“So this is really a great opportunity that we can offer for the future.”

The scan belongs to the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust who also funded and organised the expedition to find Shackleton’s ship.

The Endurance documentary is premiering at the London Film Festival on 12 October and will be released in cinemas in the UK on 14 October.

Additional reporting Kevin Church

Science & Environment

Nature decline is now nearing dangerous tipping points, WWF warns

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHuman activity is continuing to drive what conservation charity the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) calls a “catastrophic” loss of species.

From elephants in tropical forests to hawksbill turtles off the Great Barrier Reef, populations are plummeting, according to a stocktake of the world’s wildlife.

The Living Planet Report, a comprehensive overview of the state of the natural world, reveals global wildlife populations have shrunk by an average of 73% in the past 50 years.

The loss of wild spaces was “putting many ecosystems on the brink”, WWF UK head Tanya Steele said, and many habitats, from the Amazon to coral reefs, were “on the edge of very dangerous tipping points”.

© Shutterstock / COULANGES / WWF-Sweden

© Shutterstock / COULANGES / WWF-SwedenThe report is based on the Living Planet Index of more than 5,000 bird, mammal, amphibian, reptile and fish population counts over five decades.

Among many snapshots of human-induced wildlife loss, it reveals 60% of the world’s Amazon pink river dolphins have been wiped out by pollution and other threats, including mining and civil unrest.

It also captured hopeful signs of conservation success.

A sub-population of mountain gorillas in the Virunga Mountains of East Africa increased by about 3% per year between 2010 and 2016, for example.

But the WWF said these “isolated successes are not enough, amid a backdrop of the widespread destruction of habitats”.

Tom Oliver, professor of ecology at the University of Reading, who is unconnected with the report, said when this information was combined with other datasets, insect declines for example, “we can piece together a robust – and worrying – picture of global biodiversity collapse”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe report found habitat degradation and loss was the biggest threat to wildlife, followed by overexploitation, invasive species, disease, climate change and pollution.

Lead author and WWF chief scientific adviser Mike Barrett said through human action, “particularly the way that we produce and consume our food, we are increasingly losing natural habitat”.

The report also warns nature loss and climate change are fast pushing the world towards irreversible tipping points, including the potential “collapse” of the Amazon rainforest, whereby it can no longer lock away planet-warming carbon and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Please don’t just feel sad about the loss of nature,” Mr Barrett said.

“Be aware that this is now a fundamental threat to humanity and we’ve really got to do something now.”

Valentina Marconi, from the Zoological Society of London’s Institute of Zoology, told BBC News the natural world was in a “precarious position” but with urgent, collective action from world leaders “we still have the chance to reverse this”.

© WWF-Aus / Chris Johnson

© WWF-Aus / Chris Johnson © Jacqueline Lisboa / WWF-Brazil

© Jacqueline Lisboa / WWF-BrazilMs Steele said the report was an “incredible wake-up call”.

“Healthy ecosystems underpin our health, prosperity and wellbeing,” she told BBC News.

“We don’t think this sits on the shoulders of the average citizen – it’s the responsibility of business and of government.

“We need to look after our land and our most precious wild places for future generations.”

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoHyperelastic gel is one of the stretchiest materials known to science

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoHow to unsnarl a tangle of threads, according to physics

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoWould-be reality TV contestants ‘not looking real’

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago3 Day Full Body Women’s Dumbbell Only Workout

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks ago‘Running of the bulls’ festival crowds move like charged particles

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoMaxwell’s demon charges quantum batteries inside of a quantum computer

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoLiquid crystals could improve quantum communication devices

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoQuantum ‘supersolid’ matter stirred using magnets

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoSunlight-trapping device can generate temperatures over 1000°C

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoITER: Is the world’s biggest fusion experiment dead after new delay to 2035?

-

News4 weeks ago

the pick of new debut fiction

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoHow to wrap your mind around the real multiverse

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoWhy this is a golden age for life to thrive across the universe

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoOur millionaire neighbour blocks us from using public footpath & screams at us in street.. it’s like living in a WARZONE – WordupNews

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoQuantum forces used to automatically assemble tiny device

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoNerve fibres in the brain could generate quantum entanglement

-

Science & Environment2 weeks ago

Science & Environment2 weeks agoX-rays reveal half-billion-year-old insect ancestor

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoIs sharing your smartphone PIN part of a healthy relationship?

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoPhysicists are grappling with their own reproducibility crisis

-

Business2 weeks ago

Eurosceptic Andrej Babiš eyes return to power in Czech Republic

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoTime travel sci-fi novel is a rip-roaringly good thought experiment

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoLaser helps turn an electron into a coil of mass and charge

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoA slight curve helps rocks make the biggest splash

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoNuclear fusion experiment overcomes two key operating hurdles

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks ago▶️ Hamas in the West Bank: Rising Support and Deadly Attacks You Might Not Know About

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoYou’re a Hypocrite, And So Am I

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoJoshua vs Dubois: Chris Eubank Jr says ‘AJ’ could beat Tyson Fury and any other heavyweight in the world

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoCaroline Ellison aims to duck prison sentence for role in FTX collapse

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks ago▶️ Media Bias: How They Spin Attack on Hezbollah and Ignore the Reality

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks ago‘From a toaster to a server’: UK startup promises 5x ‘speed up without changing a line of code’ as it plans to take on Nvidia, AMD in the generative AI battlefield

-

Football2 weeks ago

Football2 weeks agoFootball Focus: Martin Keown on Liverpool’s Alisson Becker

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoRethinking space and time could let us do away with dark matter

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoNew investigation ordered into ‘doorstep murder’ of Alistair Wilson

-

News3 weeks ago

The Project Censored Newsletter – May 2024

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoQuantum computers may work better when they ignore causality

-

Business2 weeks ago

Should London’s tax exiles head for Spain, Italy . . . or Wales?

-

MMA2 weeks ago

MMA2 weeks agoConor McGregor challenges ‘woeful’ Belal Muhammad, tells Ilia Topuria it’s ‘on sight’

-

Sport2 weeks ago

Sport2 weeks agoWatch UFC star deliver ‘one of the most brutal knockouts ever’ that left opponent laid spark out on the canvas

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoA new kind of experiment at the Large Hadron Collider could unravel quantum reality

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoIsrael strikes Lebanese targets as Hizbollah chief warns of ‘red lines’ crossed

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoFuture of fusion: How the UK’s JET reactor paved the way for ITER

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoGet ready for Meta Connect

-

Business2 weeks ago

Ukraine faces its darkest hour

-

Health & fitness3 weeks ago

Health & fitness3 weeks agoThe secret to a six pack – and how to keep your washboard abs in 2022

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoThe ‘superfood’ taking over fields in northern India

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoUK spurns European invitation to join ITER nuclear fusion project

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoWhy we need to invoke philosophy to judge bizarre concepts in science

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoA tale of two mysteries: ghostly neutrinos and the proton decay puzzle

-

Health & fitness2 weeks ago

Health & fitness2 weeks agoThe 7 lifestyle habits you can stop now for a slimmer face by next week

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoCardano founder to meet Argentina president Javier Milei

-

Politics3 weeks ago

UK consumer confidence falls sharply amid fears of ‘painful’ budget | Economics

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoRankings Show: Is Umar Nurmagomedov a lock to become UFC champion?

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoWhy Is Everyone Excited About These Smart Insoles?

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoMeet the world's first female male model | 7.30

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoFour dead & 18 injured in horror mass shooting with victims ‘caught in crossfire’ as cops hunt multiple gunmen

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago3 Day Full Body Toning Workout for Women

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoRobo-tuna reveals how foldable fins help the speedy fish manoeuvre

-

Health & fitness3 weeks ago

Health & fitness3 weeks agoThe maps that could hold the secret to curing cancer

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoBeing in two places at once could make a quantum battery charge faster

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoHow FedEx CEO Raj Subramaniam Is Adapting to a Post-Pandemic Economy

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoDecentraland X account hacked, phishing scam targets MANA airdrop

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoLow users, sex predators kill Korean metaverses, 3AC sues Terra: Asia Express

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks agoBest Exercises if You Want to Build a Great Physique

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks agoEverything a Beginner Needs to Know About Squatting

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoCNN TÜRK – 🔴 Canlı Yayın ᴴᴰ – Canlı TV izle

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoCNN TÜRK – 🔴 Canlı Yayın ᴴᴰ – Canlı TV izle

-

Servers computers2 weeks ago

Servers computers2 weeks agoWhat are the benefits of Blade servers compared to rack servers?

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoThe best robot vacuum cleaners of 2024

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoChurch same-sex split affecting bishop appointments

-

Politics3 weeks ago

Politics3 weeks agoTrump says he will meet with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi next week

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoPhysicists have worked out how to melt any material

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoUFC Edmonton fight card revealed, including Brandon Moreno vs. Amir Albazi headliner

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoEthereum is a 'contrarian bet' into 2025, says Bitwise exec

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoHow one theory ties together everything we know about the universe

-

Business3 weeks ago

JPMorgan in talks to take over Apple credit card from Goldman Sachs

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoQuantum time travel: The experiment to ‘send a particle into the past’

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoTiny magnet could help measure gravity on the quantum scale

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoMost accurate clock ever can tick for 40 billion years without error

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoBitcoin miners steamrolled after electricity thefts, exchange ‘closure’ scam: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoDorsey’s ‘marketplace of algorithms’ could fix social media… so why hasn’t it?

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoDZ Bank partners with Boerse Stuttgart for crypto trading

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoBitcoin bulls target $64K BTC price hurdle as US stocks eye new record

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoBlockdaemon mulls 2026 IPO: Report

-

Business3 weeks ago

Thames Water seeks extension on debt terms to avoid renationalisation

-

Politics3 weeks ago

‘Appalling’ rows over Sue Gray must stop, senior ministers say | Sue Gray

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoCoinbase’s cbBTC surges to third-largest wrapped BTC token in just one week

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoUS Newspapers Diluting Democratic Discourse with Political Bias

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoiPhone 15 Pro Max Camera Review: Depth and Reach

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoBrian Tyree Henry on voicing young Megatron, his love for villain roles

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoHow do you recycle a nuclear fusion reactor? We’re about to find out

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoRedStone integrates first oracle price feeds on TON blockchain

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago‘No matter how bad it gets, there’s a lot going on with NFTs’: 24 Hours of Art, NFT Creator

-

Business3 weeks ago

How Labour donor’s largesse tarnished government’s squeaky clean image

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoBrian Tyree Henry on voicing young Megatron, his love for villain roles

-

Travel2 weeks ago

Travel2 weeks agoDelta signs codeshare agreement with SAS

-

Politics2 weeks ago

Politics2 weeks agoHope, finally? Keir Starmer’s first conference in power – podcast | News

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoMicrophone made of atom-thick graphene could be used in smartphones

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoLouisiana takes first crypto payment over Bitcoin Lightning

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoCrypto scammers orchestrate massive hack on X but barely made $8K

-

CryptoCurrency3 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency3 weeks agoTelegram bot Banana Gun’s users drained of over $1.9M

You must be logged in to post a comment Login