Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Has rapid economic growth in the world’s high-income countries come to an end? If so, did the bursting of the bubble economy in 2007 mark the turning point? Alternatively, are we at the start of a new age of rapid growth fuelled by artificial intelligence? The answers to these questions are likely to do much to shape the future of our societies, since stagnant economies partly explain our bitter politics.

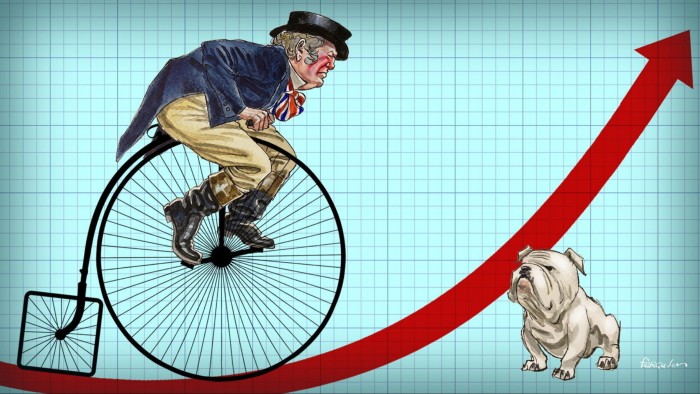

What then does the record look like and how far did it depend on unrepeatable opportunities? Here I will focus on the UK, as one of a number of countries struggling to recover dynamism. The UK has, in fact, been relatively undynamic since the second world war. Nevertheless, according to the Conference Board, UK real GDP per head rose 277 per cent between 1950 and 2023. Over the same period, US real GDP per head rose 299 per cent, French 375 per cent, German 501 per cent and Japanese 1,220 per cent. Cumulatively, standards of living have transformed.

Yet many people feel miserable. Part of the explanation for this is that growth rates have been falling. They were fastest between 1950 and 1973, the era of postwar recovery, lower between 1973 and 2007 and lower still between 2007 and 2023. Strikingly, this last period was the first in which US growth in both GDP per head and output per hour was higher than in France, Germany, Japan and the UK. Yet the level of US growth in output per hour was lower than it had been in the earlier periods.

The post-1945 growth “miracle”, especially in continental Europe and Japan, was a one-off. It was driven by the opportunities afforded by postwar reconstruction, by the mass consumption economy created by the US in the prior half century, by renewed economic integration, above all trade liberalisation, and by a high-employment, high-investment economy underpinned by better macroeconomic policies and stronger business confidence. Also significant was the cold war, which brought the US into the world permanently, in contrast to its catastrophic disengagement from the still ravaged Europe of the 1920s.

For many of today’s high-income economies, the postwar boom was an unsurpassed success. This was also true for the UK, even though its economy grew far more slowly than those of its European neighbours. Growth rates slowed quite generally from the early 1970s, but least so in the US and UK. The plausible explanation is that the big opportunities had by then been exploited. From the 1980s, they were to be found instead in emerging Asia, whose economies feasted on opportunities for growth previously enjoyed by Japan and South Korea. China was the outstanding example of such success.

New technologies also continued to be created, notably those of the digital revolution. But the argument of Robert Gordon, in his masterpiece The Rise and Fall of American Growth, that there has been a marked diminution in the overall rate of technological progress compared with its scope and scale before the second world war, is persuasive. A further reason for slowing overall productivity growth is the rising role of labour-intensive services, in which productivity is hard to increase.

There have also been inescapably transitory boosts to growth in the 20th and early 21st centuries. One was rising female labour force participation. Another was the universal move towards longer years of education, notably including tertiary education. Yet another was declining overall dependency ratios, as the “baby boomers” entered the labour force. The UK itself also benefited from membership of the EU, which it then lightly discarded.

Another transitory boost, notably to the UK public finances, came from inflation, which helped to wipe out the burden of public debt accumulated during the war. The UK public sector also enjoyed the windfall from North Sea oil revenues and the proceeds from privatisation, both of which were consumed. Unfortunately, the impact of the financial crisis and the pandemic was then to bring public debt back up, albeit not close to the heights of 1945.

A last one-off boost came from the explosive growth of the financial sector in which the UK played a more than full part. As I argued on November 5, the financial bubble “not only exaggerated the sustainable size of the financial sector, but also exaggerated the sustainable size of a whole host of ancillary activities”. This again is unrepeatable, or so at least one has to hope.

So what now lies ahead? Is the post-2007 sluggishness the norm for the old high-income economies, except, perhaps, the US? Happily, some new opportunities do exist. One is to catch up on the US, as occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. For the UK, another opportunity is to raise the lagging incomes of the “left behind” regions. Another possibility is a return to the EU’s customs union and single market. But the UK might, instead, seek to be Donald Trump’s favourite country. For the EU, the opportunity is to implement the Draghi report in full.

Yet what lies ahead for most of these economies, certainly including the UK, is managing the burden of higher public spending, notably on defence and the aged. Policymakers will also need to make economic reforms aimed at promoting competition, innovation and investment. In the UK, they must promote substantially higher savings. Policy will also need to be aimed at encouraging immigration by skilled people.

We must not least hope that AI will raise productivity without destroying the information ecosystems on which we depend. Growth has to be sustainable, ecologically and politically.

The growth slowdown is a big feature of our era. It has to be a focus for policy.

+ There are no comments

Add yours