Crypto World

SEC’s Cooled Enforcement Policy ‘Not Good’ for Crypto Industry: Congressman

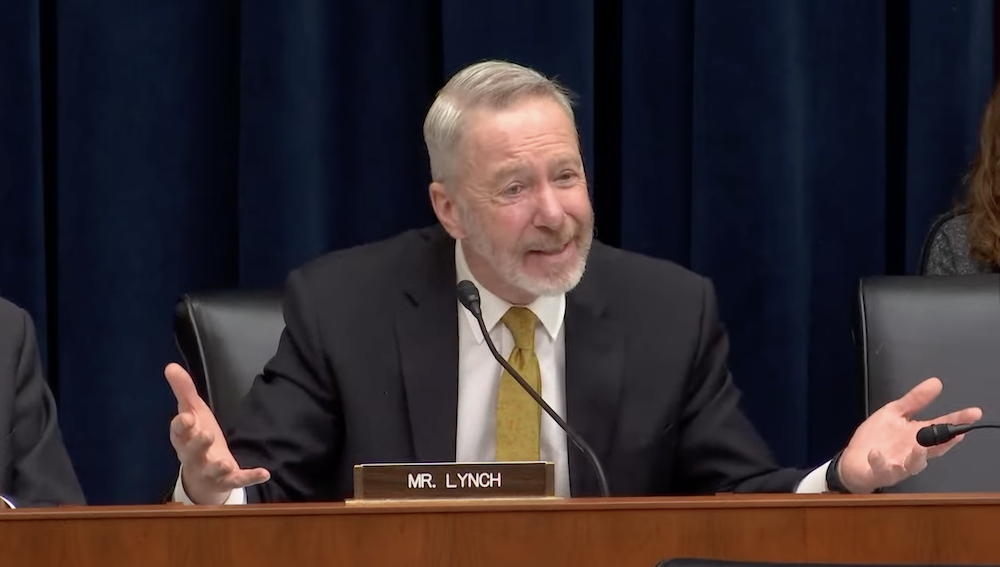

US lawmakers questioned Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Chair Paul Atkins at a hearing on Wednesday about the agency’s enforcement actions against the crypto industry and why several cases were dismissed since the leadership change.

Enforcement actions since US President Donald Trump assumed office, and appointed Atkins as SEC chair, are down by 60%, Representative Stephen Lynch said.

The Massachusetts Democrat cited the dismissal of several SEC lawsuits against the crypto industry, including the SEC’s motion to dismiss the Binance case in May 2025, as examples of the dropped enforcement cases.

Lynch also said that foreign investments in World Liberty Financial (WLFI), a decentralized finance platform linked to the Trump family, and memecoins launched by the family, were also causes for concern.

Recent reports indicate that Aryam Investment 1, an Abu Dhabi investment vehicle backed by Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the national security adviser of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), purchased 49% of the startup company behind WLFI. Lynch said:

“This is hurting the crypto industry, all these scams. Look at crypto today. I think it’s down 25% in the last month. People are losing trust, and it’s not good for crypto. It’s certainly not good for consumers, and it’s awful the reputational damage that the SEC is suffering.”

“We have a very robust enforcement effort, and we are bringing cases,” Atkins responded. The comments rehashed previous concerns voiced by Democratic lawmakers about the Trump family’s involvement in crypto and how it could effect US national security.

The comments come during a US midterm election year and could signal resistance toward crypto from Democrats, which could stall market structure legislation if the Democratic Party takes back control of at least one chamber of Congress.

Related: Trump-linked WLFI faces probe over $500M UAE crypto deal

Rep. Maxine Waters claims crypto industry pardons, dropped lawsuits are politically motivated

“These cases were dismissed, despite the fact that the SEC was winning in court, proving that the SEC’s crypto enforcement program was well-grounded in the law,” California Representative Maxine Waters said.

The crypto industry executives who benefited from the pardons and the dropped regulatory lawsuits gave “millions of dollars” to Trump and his family, Waters continued.

Waters, who is a vocal critic of both Trump and the crypto industry, has repeatedly called for probes into the president’s family’s crypto activities, characterizing the projects as a potential backdoor for foreign entities to influence Executive Branch policy through bribery.

Magazine: How crypto laws changed in 2025 — and how they’ll change in 2026

Crypto World

Strategy CEO Announces Expanded Perpetual Preferred Stock Issuance Amid Bitcoin Volatility

TLDR:

- Strategy’s “Stretch” preferred shares offer 11.25% variable dividend with monthly resets to stabilize price

- The company holds 714,000 Bitcoin worth $48 billion but stock dropped 73% since November 2024 record high

- Preferred shares represent just $7 million of funding versus $370 million in common stock sales recently

- Bitcoin fell below $67,000, down nearly 50% from October peak of $125,260, pressuring Strategy’s model

Strategy perpetual preferred stock will see increased issuance as CEO Phong Le addresses mounting investor concerns over share price volatility.

The Bitcoin treasury company announced plans to expand its “Stretch” product offering, which provides digital asset exposure with reduced risk through a monthly reset dividend mechanism.

Currently, the preferred shares represent a modest portion of Strategy’s capital structure, with $7 million issued compared to $370 million in common stock for recent Bitcoin acquisitions.

New Preferred Share Product Targets Risk-Averse Investors

Strategy has engineered the Stretch preferred shares to appeal to investors seeking digital asset exposure without extreme price swings.

The product features a variable dividend rate currently set at 11.25%, according to Le’s interview with Bloomberg Television. The monthly rate adjustments serve a specific purpose: encouraging the security to trade near its $100 par value.

“We’ve engineered something to protect investors who want access to digital capital without that volatility,” Le said in the Bloomberg Television interview.

This structure differs markedly from the company’s common stock, which has experienced severe price fluctuations tied to Bitcoin movements.

The preferred shares have accounted for just $7 million of Strategy’s recent funding activities. Meanwhile, common stock sales totaling $370 million have financed the company’s last three weekly Bitcoin purchases.

Le emphasized the product’s protective features during his television appearance, noting it provides access to digital capital without volatility.

The company holds more than 714,000 Bitcoin currently valued at approximately $48 billion. However, the common shares used to fund ongoing cryptocurrency purchases have been trading erratically.

Strategy’s funding model previously allowed the company to issue new stock at premiums above its Bitcoin holdings value.

That premium has essentially disappeared, creating challenges for the capital-raising cycle. Tightening capital markets have further complicated the company’s funding strategy.

Market Downturn Pressures Treasury Model Performance

Bitcoin’s price decline has directly affected Strategy’s financial performance and stock valuation. The cryptocurrency fell below $67,000 on Wednesday, representing nearly a 50% drop from its October peak of $125,260. Strategy’s common stock mirrored this decline, falling 5% on Wednesday alone.

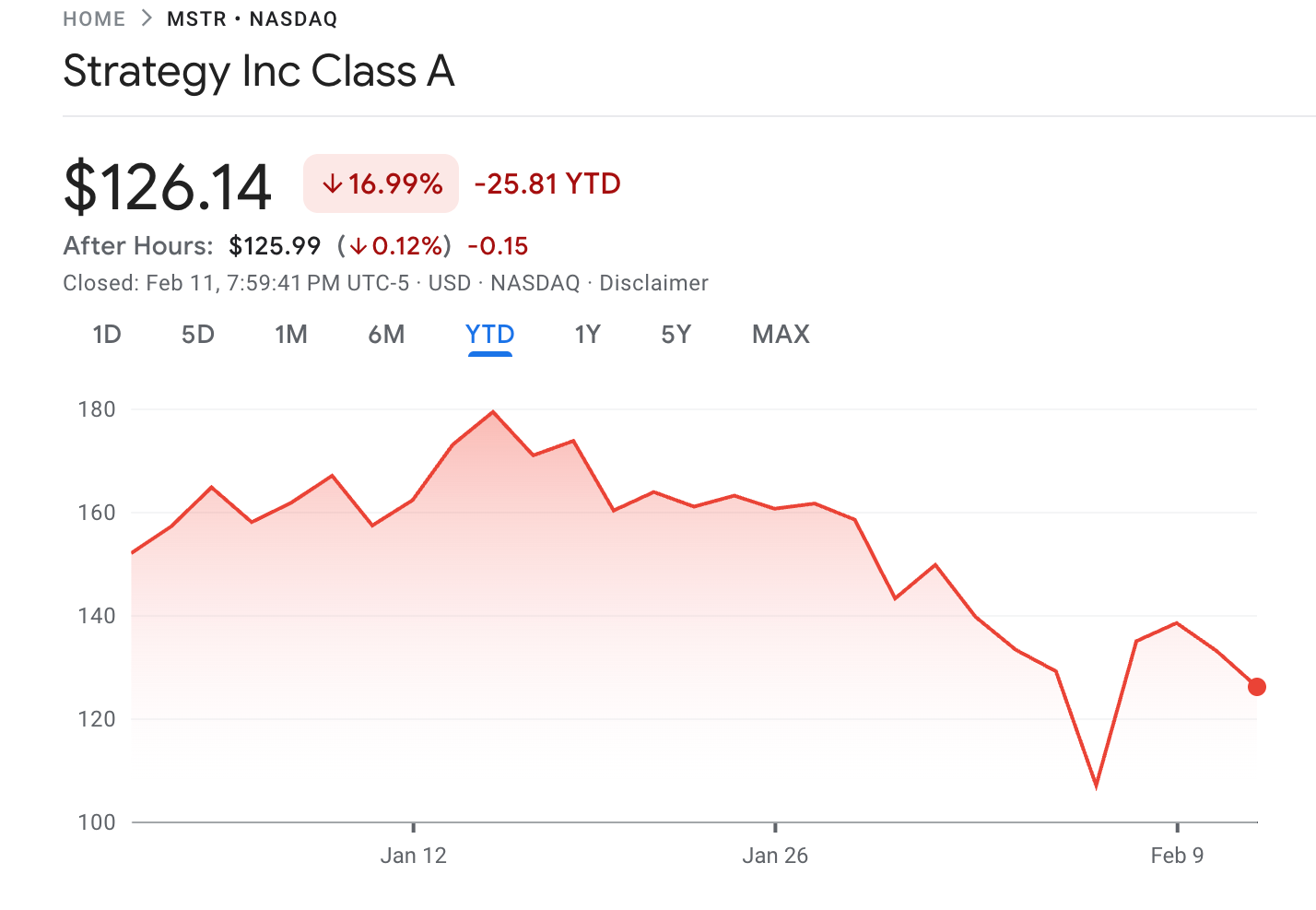

Year-to-date performance shows Strategy shares down 17% in 2026. More dramatically, the stock has plunged 73% since reaching record highs in November 2024. The company reported a net loss of $12.4 billion for the fourth quarter.

Cryptocurrencies have struggled since October’s liquidation wave damaged market confidence. The downturn has stalled Strategy’s previously successful model of issuing stock, purchasing Bitcoin, and repeating the cycle.

That approach worked when shares traded substantially above the company’s cryptocurrency holdings value.

Executive chairman and co-founder Michael Saylor addressed concerns about potential forced sales during a CNBC appearance Tuesday.

He dismissed worries that declining Bitcoin prices might compel the company to liquidate holdings as “unfounded.”

Saylor confirmed Strategy intends to continue purchasing Bitcoin every quarter despite current market conditions. The company remains committed to its Bitcoin acquisition strategy regardless of short-term price movements.

Crypto World

Why Strategy’s Preferred Stock Strategy Matters for MSTR Holders

Strategy, formerly known as MicroStrategy, plans to issue additional perpetual preferred stock in a bid to ease investor concerns over the volatility of its common shares, according to its chief executive officer.

The announcement comes as Strategy’s stock, trading under the ticker MSTR, has fallen nearly 17% year to date.

Sponsored

In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Strategy CEO Phong Le addressed Bitcoin’s price swings. He attributed its volatility to its digital characteristics. When BTC rises, Strategy’s digital asset treasury plan drives outsized gains in its common stock.

Conversely, during downturns, the shares tend to decline more sharply. He noted that Digital Asset Treasuries (DATs), including Strategy, are engineered to follow the leading cryptocurrency.

To address this dynamic, the company is promoting its perpetual preferred shares, branded “Stretch.”

“We’ve engineered something to protect investors who want access to digital capital without that volatility and that’s Stretch,” Le told Bloomberg.” To me, the story of the day is Stretch closes at $100 exactly how it was engineered to perform.”

The preferred shares offer a variable dividend, currently set at 11.25%, with the rate reset monthly to encourage trading near the $100 par value.

It’s worth noting that preferred stock has so far represented only a small portion of Strategy’s capital-raising activity. The company sold approximately $370 million in common stock and about $7 million in perpetual preferred shares to fund its previous three weekly Bitcoin purchases.

Sponsored

However, Le said, Strategy is actively educating investors about what preferred shares can do.

“It takes some seasoning. It takes some marketing,” he said. “This year, we have seen extremely high liquidity with our preferreds, about 150 times other preferreds, and as we go throughout the course of this year, we expect Stretch to be a big product for us. We will start to transition from equity capital to preferred capital.”

MicroStrategy’s Bitcoin Bet Under Pressure With Shares Trading Below Net Asset Value

The shift could prove important as Strategy’s traditional funding model faces pressure. Strategy continues to expand its Bitcoin holdings, purchasing more than 1,000 BTC earlier this week. As of the latest data, the firm holds 714,644 BTC.

Sponsored

However, the recent decline in Bitcoin’s price has weighed heavily on the company’s balance sheet. At current market prices of around $67,422 per coin, Bitcoin is trading well below Strategy’s average purchase price of approximately $76,056. As a result, the company’s holdings reflect an unrealized loss of roughly $6.1 billion.

The company’s common stock has mirrored that decline, falling 5% on Wednesday alone. MSTR is roughly down 17% so far this year. In comparison, Bitcoin has fallen more than 22% over the same period.

As mentioned before, Strategy’s Bitcoin accumulation strategy has relied more on equity issuance. A key metric in this model is its multiple to net asset value, or mNAV, which measures how the company’s stock trades relative to the value of its Bitcoin per share.

According to SaylorTracker data, Strategy’s diluted mNAV was approximately 0.95x, indicating the stock traded at a discount to the Bitcoin backing each share.

Sponsored

That discount complicates the company’s approach. When shares trade above net asset value, Strategy can issue stock, purchase additional Bitcoin, and potentially create accretive value for shareholders. When shares trade below net asset value, new issuance risks diluting shareholders instead.

By increasing its reliance on perpetual preferred stock, Strategy appears to be adjusting its capital structure to sustain its Bitcoin acquisition strategy while attempting to address investor concerns over volatility and valuation pressure.

For MSTR shareholders, the shift toward perpetual preferred stock could reduce dilution risk. By relying less on common equity issuance, Strategy may preserve Bitcoin per share and limit pressure from discounted share sales.

However, the move also introduces higher fixed dividend obligations, increasing financial commitments that could weigh on the company if Bitcoin remains under pressure. Ultimately, the plan reshapes the risk profile rather than eliminating the underlying volatility tied to its Bitcoin treasury.

Crypto World

UK appoints HSBC for blockchain bond pilot

Britain is positioning itself to become the first G7 nation to issue sovereign debt on the blockchain, appointing banking giant HSBC and law firm Ashurst to steer a digital gilt trial expected this year, according to the Financial Times.

The Treasury’s selection of the two firms aims to quell growing criticism that the U.K. has been dragging its feet on tokenized government bonds. While Chancellor Rachel Reeves unveiled the pilot plan in late 2024, other jurisdictions including Hong Kong have already crossed the finish line with their own digital sovereign issuances.

The pilot aims to slash settlement time and operational costs for market participants. The experiment will run within the Bank of England’s “digital sandbox,” a controlled environment where financial innovations can operate under relaxed regulatory constraints.

HSBC has experience in digital debt offerings, having orchestrated over $3.5 billion in digital bond issuances through its proprietary Orion blockchain — including Hong Kong’s $1.3 billion green bond last year, one of the largest tokenized debt sales globally.

On Wednesday, Hong Kong Financial Secretary Paul Chan Mo-po said the multicurrency offering helped boost liquidity on the product.

“We will regularize the issuance of tokenized green bonds,” he said at CoinDesk’s Consensus Hong Kong conference, which could support further adoption.

Crypto World

XRP Price Analysis: Critical $1.65 Level Tests Relief Rally While $0.90 Target Looms

TLDR:

- XRP reached first relief target at $1.52 after RSI hit multi-year lows during last week’s selloff

- Critical $1.65 resistance zone will determine if XRP continues rally or drops toward $0.90 support

- Ripple partners with Aviva Investors to tokenize real-world assets on XRP Ledger throughout 2026

- Analysts warn against panic selling as XRP flirts with correction lows and potential bullish setup

XRP price action shows signs of relief following last week’s sharp decline that pushed technical indicators to extreme levels.

Market analysts track the $1.65 resistance zone as a critical threshold for the digital asset’s near-term direction. A failure at this level could open the door to targets as low as $0.90.

The current phase presents multiple scenarios for traders watching key support and resistance zones.

Critical Price Levels Define XRP’s Next Move

XRP has entered a Wave 4 relief phase after last Thursday’s massive selloff tested market sentiment. Technical analyst CasiTrades noted the decline pushed RSI to multi-year lows across trading platforms.

The subsequent bounce has already reached the first Wave 4 target near $1.52. This price point coincides with the 0.382 retracement level and macro 0.65 fibonacci zone.

The market now approaches a decisive juncture at the $1.65 resistance area. This level represents the 0.5 retracement and macro 0.618 fibonacci extension.

The asset’s ability to flip this zone into support will determine the next directional move. Technical patterns suggest two distinct paths forward based on price behavior at current levels.

A rejection at $1.65 could trigger another wave down to lower support zones. CasiTrades outlined potential targets at $1.09 and approximately $0.90 in this scenario.

These levels would mark the completion of a corrective structure from recent highs. The analyst emphasized that RSI has reset enough to allow for such a move.

However, the relief bounce offers an alternative bullish scenario for market participants. If XRP successfully reclaims $1.65 and holds it as support, buying pressure could increase.

Traders would then wait for confirmation through a back-test of this support level. The analyst cautioned against panic selling given the asset’s proximity to correction lows.

Ripple Partnership Adds Fundamental Support

Ripple announced a collaboration with Aviva Investors to tokenize real-world assets on XRP Ledger. Reece Merrick from Ripple shared the development, marking the first partnership with a European investment management firm.

The initiative will bring traditional fund structures to the blockchain throughout 2026. Aviva Investors cited the ledger’s speed, cost efficiency, and sustainability as key factors.

The partnership addresses growing institutional interest in blockchain-based asset management solutions. Traditional finance firms continue exploring distributed ledger technology for operational advantages.

XRP Ledger provides the infrastructure necessary for large-scale tokenization projects. European investment managers show increasing willingness to adopt blockchain platforms.

Asset tokenization represents a expanding sector within the digital asset industry. The collaboration aims to bridge institutional finance with blockchain utility at scale. Real-world assets moving onto public ledgers could drive long-term adoption metrics. This development provides fundamental support independent of short-term price fluctuations.

The announcement comes as XRP navigates technical correction levels on price charts. Fundamental developments often diverge from immediate market sentiment during volatile periods.

Long-term investors may view the partnership as validation of the ledger’s institutional appeal. Technical traders meanwhile focus on price action to determine entry and exit points.

Crypto World

Strategy to issue more preferred stock to reduce volatility

Strategy is turning to preferred stock to keep buying Bitcoin while easing pressure from market swings.

Summary

- Strategy is issuing more preferred shares to fund Bitcoin purchases.

- The “Stretch” stock pays an 11.25% variable dividend and aims for price stability.

- The move targets investors seeking crypto exposure with lower risk.

Strategy is expanding its use of preferred stock as it looks for new ways to fund Bitcoin purchases while reducing pressure from market volatility.

The move comes as the company’s share price continues to closely track swings in the cryptocurrency market.

A new approach to managing risk

In a Feb. 12 interview with Bloomberg, chief executive officer Phong Le said the company is offering more perpetual preferred shares to attract investors who want exposure to digital assets without extreme price changes. The product, known as “Stretch,” pays a variable dividend that is adjusted each month.

The current dividend rate stands at 11.25%. The structure is designed to keep the stock trading close to its $100 par value. This helps limit sharp price movements that are common in Strategy’s regular shares.

Preferred shares sit above common stock in the company’s capital structure but below debt. They usually offer a steady income and priority on dividends, while giving up voting rights. This makes them appealing to investors who value stability over rapid growth.

Funding Bitcoin while limiting volatility

Over the past three weeks, Strategy raised about $370 million through common stock sales and another $7 million through preferred shares. The funds were used to buy more Bitcoin (BTC), pushing the company’s total holdings above 714,000 BTC, worth roughly $48 billion.

For years, Strategy’s business model has been built around using capital markets to accumulate Bitcoin. As a result, its stock often behaves like a leveraged version of the cryptocurrency. When Bitcoin rises, the stock tends to surge. When prices fall, losses are often amplified.

Bitcoin has dropped around 50% from its recent peak, which has weighed heavily on Strategy’s shares. This slowdown has made it harder for the company to rely only on common stock sales for funding.

Preferred stock offers another option. The steady dividend and price controls are meant to attract institutions such as pension funds, insurers, and banks. These investors often prefer predictable returns rather than high-risk exposure.

Co-founder Michael Saylor has repeatedly said the company has no plans to sell its Bitcoin. Strategy intends to continue buying more each quarter, regardless of market conditions.

Analysts say preferred shares also strengthen the company’s balance sheet. Compared with convertible bonds, they reduce refinancing risk and limit sudden dilution for existing shareholders.

Strategy raised about $5.5 billion through several preferred stock offerings in 2025. The latest issuance continues that pattern, showing that the company sees long-term value in this funding model.

Crypto World

Paxos Labs Launches Privacy-Preserving USAD Stablecoin on Aleo Network

TLDR:

- USAD offers privacy-preserving transactions while maintaining regulatory oversight capabilities

- Paxos leverages its established infrastructure to issue compliant stablecoins on Aleo’s platform

- Circle previously partnered with Aleo for USDCx, showing competitive interest in privacy solutions

- Aleo raised $200 million at $1.45 billion valuation from SoftBank, a16z, and Coinbase Ventures

Privacy-preserving USAD stablecoin has launched on the Aleo Layer 1 mainnet through a partnership between Paxos Labs and Aleo Network.

The collaboration introduces digital dollars to a zero-knowledge powered environment. The stablecoin offers privacy and programmability features for enterprise users.

Aleo previously partnered with rival issuer Circle to pilot USDCx. The launch reflects growing institutional demand for privacy-focused blockchain solutions.

Partnership Details and Technical Framework

Paxos Labs will issue USAD using its established infrastructure to meet regulatory oversight requirements. The stablecoin operates on Aleo’s zero-knowledge cryptography platform.

The technology provides end-to-end encryption by default. The platform conceals participant identities, wallet addresses, and transaction amounts from public view.

Aleo COO Leena Im explained the stablecoin design incorporates Paxos’ issuance infrastructure. The system meets “oversight requirements while still protecting sensitive user information,” Im noted.

The balance between privacy and oversight represents a core technical achievement. Selective disclosure capabilities allow for regulatory compliance without compromising user confidentiality.

USAD supports traditional payment functions as well as advanced programmable applications. The stablecoin enables use cases difficult to execute on transparent blockchains.

Target applications include discreet payroll processing, business-to-business payments, and anonymous decentralized finance activities. Furthermore, enterprises can embed trusted digital currency into their platforms.

Paxos Labs co-founder Bhau Kotecha emphasized the strategic value of the collaboration. “Working with Aleo, we are bringing digital dollars into an environment where privacy and programmability are built in from the start,” Kotecha said.

He added that enterprises gain “a way to embed money they can trust.” The executive expects more organizations to deploy custom assets on blockchain platforms.

Kotecha noted that stablecoins continue to impact traditional financial rails. He stated Aleo and its team are “already ahead of the curve” on this development.

The trend toward programmable money reshapes financial infrastructure. Organizations increasingly value privacy-preserving transaction capabilities for commercial operations.

Market Context and Company Background

The launch occurs amid rising interest in institutional-grade privacy solutions for blockchain assets. Businesses want blockchain benefits without exposing sensitive commercial details on transparent networks.

Circle previously selected Aleo to develop USDCx, a privacy-focused version of its flagship token. The competitive landscape shows multiple issuers exploring privacy-preserving stablecoin technology.

Paxos has established experience in the stablecoin sector through partnerships with major platforms. The company previously issued stablecoins for PayPal and Binance.

Moreover, Paxos plays a role in the Global Dollar consortium. The USDG initiative includes Anchorage Digital, Bullish, Kraken, OKX, Robinhood, and World.

Aleo Network launched its mainnet in September 2024 after several years of development. The Layer 1 project raised $200 million in a 2022 Series B funding round.

The company achieved a valuation of $1.45 billion during the financing. SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2 and Kora Management co-led the investment.

The project has attracted backing from prominent investors across the blockchain ecosystem. Notable supporters include a16z, Softbank, Coinbase Ventures, Samsung Next, and Tiger Global.

The investor roster demonstrates confidence in zero-knowledge technology applications. Aleo’s platform aims to enable privacy-focused blockchain solutions for enterprise adoption.

Crypto World

Thailand Approves Bitcoin For Derivatives Trading Markets

Thailand’s government on Tuesday approved the Finance Ministry’s proposal allowing digital assets to be used as underlying assets in the country’s derivatives and capital markets.

The move aims to modernize Thailand’s derivatives markets in line with international standards, strengthen regulatory oversight and investor protection, and position itself as a regional hub for institutional crypto trading, the Bangkok Post reported.

The country’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) will amend the Derivatives Act to enable these new asset classes, which include Bitcoin (BTC) and carbon credits.

“The decision to formally recognize digital assets, including cryptocurrencies and digital tokens […] reflects a growing understanding that digital assets are no longer merely speculative instruments, but an emerging asset class with the potential to reshape the foundations of capital markets,” said Nirun Fuwattananukul, chief executive of Binance Thailand.

He added that it was a “watershed moment” for the country’s capital markets, sending a “strong signal” that Thailand is positioning itself as a “forward-looking leader” in Southeast Asia’s digital economy.

Strengthening crypto recognition for investors

Thailand is targeting wealthy institutional investors as it expands its crypto ambitions. The move also aligns with the Stock Exchange of Thailand’s plans to introduce Bitcoin futures and exchange-traded products in 2026.

Related: Thailand plans crypto ETF rules as institutional interest increases

SEC secretary-general Pornanong Budsaratragoon said the move will “strengthen the recognition of crypto as an asset class, promote market inclusiveness, enhance portfolio diversification, and improve risk management for investors.”

Still no crypto payments in Thailand

Retail trading remains popular in Thailand, with the Kingdom’s largest exchange, Bitkub, seeing daily volumes of $65 million, according to CoinMarketCap.

However, the central bank has outlawed crypto payments, and consumer stablecoin use remains restricted.

The government launched an app in August for short-term tourists to convert crypto to local currency, but users must undergo stringent Know Your Customer (KYC) and customer due diligence checks, and usage remains restricted to government-approved outlets.

Thailand launched a campaign in January against so-called “gray money,” targeting crypto as part of an effort to combat money laundering.

Magazine: Bitcoin difficulty plunges, Buterin sells off Ethereum: Hodler’s Digest

Crypto World

Saylor Reacts to MSTR Bear Market

Strategy, formerly known as MicroStrategy, remains locked in a persistent bear market. The Michael Saylor-led company has struggled to regain momentum as its stock mirrors Bitcoin’s decline.

As Bitcoin corrects, Strategy stock follows, reinforcing volatility and heightening sensitivity to digital asset sentiment shifts.

Sponsored

Sponsored

MSTR Is Breaking Out

About a week ago, the Chaikin Money Flow formed a bullish divergence against price. While MSTR recorded a lower low, CMF posted a higher reading. This divergence signaled improving capital inflows despite falling prices, suggesting selective accumulation beneath the surface.

The short-term impact was visible as the MSTR price rebounded roughly 20% across Friday and Monday trading sessions. However, the broader technical structure remains fragile. Macro indicators still lean bearish, and sustained upside depends on stronger conviction returning to Bitcoin markets.

Want more token insights like this? Sign up for Editor Harsh Notariya’s Daily Crypto Newsletter here.

Can The Oversold Stock Mirror 2022 Recovery?

The Relative Strength Index has hovered near oversold territory since November 2025. A brief improvement appeared in January before RSI fell below 30.0 again last week. An RSI below 30 often signals oversold conditions, which historically precede technical rebounds.

A similar setup occurred in May 2022. At that time, MSTR rebounded 123% after entering oversold territory. That rally unfolded despite Bitcoin experiencing uneven momentum. Investors treated Strategy as a distinct equity with its own growth narrative.

Sponsored

Sponsored

This cycle differs materially. Strategy’s corporate identity is now deeply connected to its Bitcoin holdings strategy. Demand for MSTR shares increasingly reflects sentiment toward Bitcoin accumulation.

MSTR Follows Bitcoin

In prior downturns, the MSTR price occasionally moved independently of Bitcoin. During earlier oversold phases, the stock rallied even as Bitcoin corrected. That divergence highlighted investor confidence in Strategy’s enterprise software operations and balance sheet flexibility.

Today, correlation metrics show stronger alignment between MSTR and Bitcoin price action. Since November 2025, Bitcoin’s steady decline has exerted downward pressure on Strategy shares. Market participants increasingly treat the stock as a Bitcoin-linked instrument rather than a standalone tech equity.

Sponsored

Sponsored

As a result, Strategy’s outlook now depends heavily on Bitcoin’s next move. If Bitcoin stabilizes or enters accumulation, MSTR may follow. Conversely, extended crypto weakness could prolong the bear phase in Strategy stock despite internal accumulation policies.

Saylor Remains Bullish

Michael Saylor, founder of Strategy, is unbothered by the decline in MSTR’s value. During an interview with CNBC, Saylor highlighted that the company is far from affected by BTC’s decline. He stated that volatility is the bug, but volatility is also the feature. He further strengthened the company’s outlook of accumulation over selling.

“We will not be selling. Instead, I believe we will be buying Bitcoin every quarter forever,” Saylor stated.

Sponsored

Sponsored

Thus, Strategy will likely continue buying BTC, and MSTR will continue following its trajectory until the market changes drastically for one of them.

MSTR Price Targets Identified

MSTR price trades near $133, hovering around the $137 region aligned with the 61.8% Fibonacci retracement level. This technical zone acts as a critical inflection point. Future direction will likely depend on Bitcoin price stability and broader crypto market sentiment.

If bearish conditions persist, recent gains could fade quickly. A drop below $122, corresponding to the 0.786 Fibonacci level, may expose $104, the February low. Should selling intensify further, the next structural support lies near $83.

On the upside, the immediate recovery target sits near $157. Reclaiming that level would offset recent losses and improve technical structure. If Saylor maintains Strategy’s Bitcoin accumulation stance, sustained commitment could attract renewed investor interest and support a stronger rebound in MSTR shares.

Crypto World

XRP Set for Breakout? Analyst Flags Bullish Channel

Analyst flags XRP monthly support at $0.85–$0.95 as potential entry for “smart money” amid recent 34% monthly decline.

XRP is trading at $1.37, down nearly 15% over the past week and 33% in the last 30 days, as bearish sentiment continues to weigh on the Ripple token.

However, a widely followed analyst says the monthly chart is showing a long-term ascending channel with support at $0.85–$0.95, a zone he believes could mark the entry point for institutional capital that has yet to return to the market.

Monthly Structure Shows Nine-Year Support Zone

The technical case for a potential reversal rests entirely on the monthly timeframe, according to analyst Arthur, who posted a detailed thread on X early Wednesday. His chart tracks XRP from March 2017 to the present, with each candlestick representing a full month of trading. The lower boundary of an ascending channel, tested repeatedly over nine years, now sits at $0.85–$0.95, which is roughly 30% below current prices.

“This is a monthly structural read, backed by macro and long-term volume behavior,” Arthur wrote. “The bottom of the monthly channel may very well represent the area where ‘smart money’ returns.”

He pointed to volume as the missing ingredient. The largest volume spike in XRP history occurred between November 2020 and April 2021. According to him, the 2024 rally, which pushed XRP above $2, saw four times less volume.

“The real money hasn’t returned yet,” he said. “What we saw in 2024 was whales and some funds. Not the large institutional flow that changes a market forever.”

Derivatives data supports the view that speculative positioning has cooled, with analysis from Arab Chain showing that in the last 30 days, XRP futures open interest dropped by about 1.8 billion XRP on Bybit and 1.6 billion on Binance. Kraken also posted a decline of about 1.5 billion XRP.

The contraction suggests traders are closing leveraged positions rather than building new ones, a behavior typically seen during transitional phases before a new trend emerges.

Macro Backdrop Has Shifted

The analyst’s optimism is not based on chart patterns alone. He cited five macro developments that distinguish early 2026 from previous cycles, including regulatory clarity following the conclusion of Ripple’s SEC lawsuit, the launch and scaling of RLUSD, and institutional integration of Ripple’s technology.

You may also like:

Arthur also pointed to the accelerating tokenization narrative and what he called “real institutional infrastructure” that is now in place.

“Technical analysis is always driven by macro,” the market observer said. “And the macro is pointing up.”

XRP has a history of delivering sharp recoveries from extended downturns. For example, during the 2018 bear market, the asset traded near $0.30 for months before rallying to $1.70 in April 2021. It again bottomed around $0.35 in spring 2022 and remained range-bound until November 2024, when it climbed above $2 and later hit an all-time high of $3.65 in July 2025.

SECRET PARTNERSHIP BONUS for CryptoPotato readers: Use this link to register and unlock $1,500 in exclusive BingX Exchange rewards (limited time offer).

Crypto World

Cardano founder Charles Hoskinson says Midnight won’t chase Monero, ZCash users

Cardano founder Charles Hoskinson said that privacy-focused blockchain Midnight doesn’t have plans to onboard privacy maxis from the zcash and monero communities to the Midnight chain.

“You don’t try to get anybody from Monero or ZCash over,” he said during a Q&A session at Consensus Hong Kong on Thursday.

“They certainly will come in their own time, but they’re a different demographic,” he said. “Those are people that wake up every day and they really care about privacy, and they matter and they’re important, but what we’re going for is the billions of people that don’t know they need privacy but give it to them by default.”

Midnight announced Thursday that its mainnet will go live in March as a partner chain to Cardano.

Hoskinson then claimed the ethos of privacy is not as simplistic as the monero and zcash communities often allude to.

“What Monero and ZCash have been trying to convince people is it’s like a light switch. We’re private. The switch is on. Everybody else is not. The switch is off. That’s not how that works,” he said.

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoWhy Israel is blocking foreign journalists from entering

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoJD Vance booed as Team USA enters Winter Olympics opening ceremony

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoMia Brookes misses out on Winter Olympics medal in snowboard big air

-

Business3 days ago

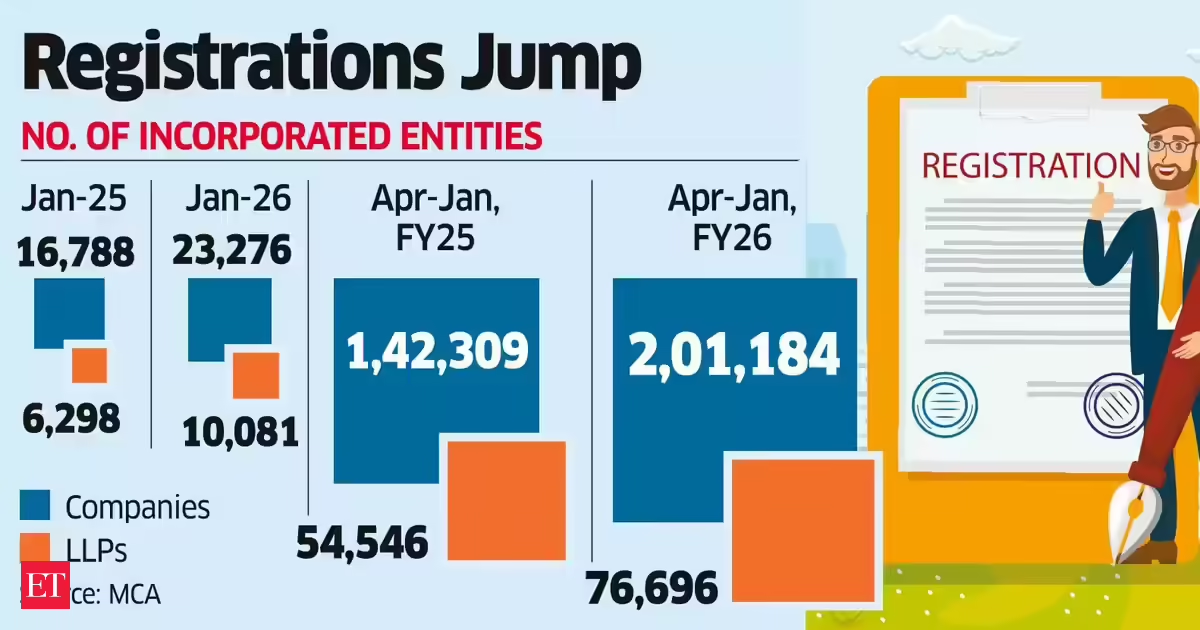

Business3 days agoLLP registrations cross 10,000 mark for first time in Jan

-

Tech5 days ago

Tech5 days agoFirst multi-coronavirus vaccine enters human testing, built on UW Medicine technology

-

Sports5 hours ago

Sports5 hours agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoCostco introduces fresh batch of new bakery and frozen foods: report

-

Tech1 day ago

Tech1 day agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoWinter Olympics 2026: Team GB’s Mia Brookes through to snowboard big air final, and curling pair beat Italy

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoBenjamin Karl strips clothes celebrating snowboard gold medal at Olympics

-

Sports5 days ago

Former Viking Enters Hall of Fame

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoThe Health Dangers Of Browning Your Food

-

Sports6 days ago

New and Huge Defender Enter Vikings’ Mock Draft Orbit

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoJulius Baer CEO calls for Swiss public register of rogue bankers to protect reputation

-

NewsBeat6 days ago

NewsBeat6 days agoSavannah Guthrie’s mother’s blood was found on porch of home, police confirm as search enters sixth day: Live

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoQuiz enters administration for third time

-

Crypto World7 hours ago

Crypto World7 hours agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoBlockchain.com wins UK registration nearly four years after abandoning FCA process

-

Video2 hours ago

Video2 hours agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoU.S. BTC ETFs register back-to-back inflows for first time in a month

![2B. NAMNA YA KUPATA UHURU WA KIFEDHA [ FINANCIAL FREEDOM ] KIBIBLIA // MWL CHRISTOPHER MWAKASEGE:](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1770875187_maxresdefault-80x80.jpg)