Video

We Spent 1,00,000 On Viral Adult Money Gadgets!!!

We spent ₹1,00,000+ on viral “Adult Money” gadgets Instagram keeps showing us—from flying RC cars to AI robot dogs to the HotWheels set we NEVER got as kids. Some were absolute GOAT tier, others complete scams. Here’s everything that’s actually worth your money. Your childhood self will thank you. 🎮🚗

Here are product links:

1. Flying Car – https://jaimantoys.com/products/sg900pro-dual-mode-2-in-1-flying-car-drone-rc-air-ground-vehicle-with-led-lights-green-copy?variant=47000704057574

2. Retro Gaming Console – https://www.amazon.in/dp/B0FQJPH6H5?&linkCode=sl2&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=81e3c08a3d8cc5d6547c21ffad3900a0&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

3. Tic Tac Toe – https://www.amazon.in/Tic-Tac-Toe-Handheld-Electronic-Educational-Portable/dp/B0GCW3RLCG/ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

4. 4WD RC Car – https://www.amazon.in/dp/B0FH4Z9BY7?th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=2c181bfdbe70f8ebd94a9ec85e715f83&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

5. Smart Dog – https://www.amazon.in/Programmable-Storytelling-Water-Bomb-Interactive-Educational/dp/B0G2SXZPRJ/ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

6. 4WD Drift Car – https://www.amazon.in/Gaadoo-Controlled-Drifting-Batteries-Multicolor/dp/B0F8PDTPYL/ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

7. Dual Mode Blaster Gun – https://www.amazon.in/gp/product/B0D72J2KFM?ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

8. Hot Wheels Car – https://www.amazon.in/Hot-Wheels-Action-Dual-Loop/dp/B07PPDG8L3/ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

Hot Wheels Track Builder Set – https://www.amazon.in/Hot-Wheels-Track-Component-Building/dp/B0721CGJMT/ie=UTF8&th=1&linkCode=sl1&tag=r0bc-21&linkId=1d94bca09cef3d9aa7ba04a86c2852bc&language=en_IN&ref_=as_li_ss_tl

🚀 We Are Hiring! APPLY HERE: https://techwiser.com/we-are-hiring

🌟 Please leave a LIKE ❤️ and SUBSCRIBE For More Videos Like This! 🌟

——————————————————————————

🌟 Follow Us Other Social Media Platforms 🌟

🐦 Twitter: https://twitter.com/TechWiser

👩👧👦 Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/techwiser

📷 Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/techwiser

🌍 Website: http://techwiser.com

——————————————————————————

🌟 Team TechWiser 🌟

🙋🏻♂️ Video Producer: https://www.instagram.com/praaatiiik

📹 Channel Manager: https://www.instagram.com/mr_dinesh_ji

👨🏻💻 Script: https://www.instagram.com/shoubhik_sadhu/

👨🏻💻 Video Editor: https://www.instagram.com/y_singhal/

👨🏻💻 Video Editor: https://www.instagram.com/development_enthusiast/

👨🏻💻 Video Editor: https://www.instagram.com/sathvikpanchumarthy/

👨🏻💻 Video Editor: https://www.instagram.com/yuv.3gp/

#Tech #Smartphones #TeamTechWiser

source

Video

FINANCE : La folie des robots traders

Le monde de la finance a basculé dans une ère où l’humain n’a plus sa place. Ce documentaire explore la réalité du trading à haute fréquence, où des milliers d’ordinateurs échangent des millions d’actions à la microseconde, sans aucune régulation. Du “Flash Crack” de 2010 qui a pulvérisé 1000 milliards de dollars en quelques minutes à l’impuissance des politiques face à cette spéculation invisible, découvrez comment ces robots traders menacent la stabilité de notre économie réelle. Un portrait factuel sur une finance devenue folle, entre prouesse technologique et danger démocratique majeur.

Réalisateur : Iréne Bénéfice

Olivier Toscer

🔗 Playlist Documentaire Société ici : https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLi5quiu_seE2TMce4bcNFspS_06rEXzlt]

💬 Faites-vous encore confiance au système financier actuel ?

00:00 — Introduction : Bienvenue dans le monde merveilleux des robots

01:15 — HFT : Le trading à haute fréquence expliqué

18:40 — Flash Crack : Le jour où Wall Street a perdu le contrôle

35:20 — Impact : La spéculation algorithmique contre l’économie réelle

52:10 — Régulation : Pourquoi les politiques n’arrivent pas à taxer les robots

01:05:40 — Bilan : Le temps de la politique face à la microseconde financière

#FinanceFolle #Trading #Bourse #Economie #Documentaire

source

Video

Love and Money: Financial Decisions People Immediately Regret

💵 Create a free budget and find more margin with EveryDollar: https://ramsey.solutions/l0nqve

Is love blind? Some of your financial decisions certainly make it seem that way! Today we’re reacting to people’s biggest money mistakes made on behalf of their loved ones.

Next Steps:

• 🎙️ Catch our episode Date Nights From $0 to $10,000? We’ve Got You Covered! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNTgoyrhTlo

• 🍸 Follow Smart Money Happy Hour on TikTok @smartmoneyhappyhour: https://www.tiktok.com/@smartmoneyhappyhour

• 📱 Submit a Guilty As Charged question for Rachel and George! Leave us a voicemail with your question at 877-306-1517 or send a DM to @rachelcruze or @georgekamel on Instagram! Be sure to type “GUILTY?” at the top of your message so we don’t miss it.

Connect With Our Sponsors:

• Check out the FAIRWINDS Credit Union exclusive account bundle. ⮕ https://www.fairwinds.org/ramsey

• Get 20% off when you join DeleteMe. ⮕ https://www.joindeleteme.com/smartmoney

• Get 20% off with code SMARTMONEY at Cozy Earth. ⮕ https://www.cozyearth.com/smartmoney

Today’s Happy Hour Special: 🍹 Trophy Wife Spritz

Recipe from Fly Girl Bartending: https://www.instagram.com/reels/DA_ZyRlP4TR/

• Mint leaves

• 1/2 ounce honey

• 3 ounces club soda

• 3 ounces nonalcoholic sparkling wine

• Grapefruit

Instructions: Place mint in the bottom of a wine glass. Add honey and club soda and stir. Fill the glass with ice and top with sparkling wine. Garnish with mint and grapefruit and enjoy!

Explore More From Ramsey Network:

💡 The Rachel Cruze Show ⮕ https://ter.li/zn5yjl

💰 George Kamel ⮕ https://ter.li/jxpkwe

🎙️ The Ramsey Show ⮕ https://ter.li/dhaofd

💸 The Ramsey Show Highlights ⮕ https://ter.li/ls738t

🧠 The Dr. John Delony Show ⮕ https://ter.li/jy41yb

🪑 Front Row Seat with Ken Coleman ⮕ https://ter.li/u5ow3z

📈 EntreLeadership ⮕ https://ter.li/nmira1

Ramsey Solutions Privacy Policy:

https://www.ramseysolutions.com/company/policies/privacy-policy

Products:

Breaking Free From Broke: https://ter.li/97f5nl

The Total Money Makeover – Updated and Expanded Edition: https://ter.li/7nth89

I’m Glad for What I Have: https://ter.li/phzq5l

Questions for Humans: https://ter.li/kx0grn

Baby Steps Millionaires: https://ter.li/rjpv7u

source

Video

My biggest concern in Bitcoin

The fixed supply (21 million) is one of the biggest value propositions for Bitcoin – and it seems to be in jeopardy.

As new financial products are created, the ability to create fake or paper Bitcoin becomes much easier.

We have to normalized proof-of-reserves in Bitcoin if we ever want to know the true price of Bitcoin.

#bitcoin #btc #soundmoney #investing #gold #silver #digitalassets #cryptocurrency #sats #88sats #maplebitcoin #wealthbuilding

source

Video

AI IS GOING TO BE YOUR NEXT FINANCIAL ADVISOR? #bitcoin #ai #scary #xrp #coinbase

AI IS GOING TO BE YOUR NEXT FINANCIAL ADVISOR? #bitcoin #ai #scary #xrp

source

Video

A Day in the Life of a Financial Advisor | Indeed

Get better job matches when you complete your Indeed profile: https://go.indeed.com/4ER6C8

Ever been interested in becoming a financial advisor? Whether you’re considering a career in finance or simply curious about the day-to-day life of a financial advisor, this video will provide valuable insights and inspiration.

We follow Eric, a seasoned financial advisor, through a typical day work day. From client meetings to tips on investment analysis, you’ll learn about the tools and strategies used by financial advisors to help their clients meet their financial goals. Watch for tips from Eric on how to get into the field of working finance and gain insight into the interpersonal skills needed to succeed in the field.

0:00 – Intro

0:09 – Financial advisor career path

0:50 – Starting out the day

1:22 – First client of the day

2:40 – Second client of the day

4:15 – Third client of the day

5:04 – Advice for someone wanting to become a financial advisor

If you enjoyed this episode, watch more career paths videos here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL6qIzGkkiXFFb5ck2zmUDnI7nhN7rFZX9

Salary estimates are based on 16,718 salaries submitted anonymously to Indeed by financial advisor employees, users, and collected from past and present job posts on Indeed in the past 36 months. The typical tenure for a Financial Advisor is less than 1 year.*

Follow Indeed!

https://www.facebook.com/Indeed

https://twitter.com/indeed

https://www.instagram.com/indeedworks/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/indeed-com/

@indeed

Indeed is the world’s #1 job site**, with over 300 million global monthly unique visitors***. We provide free access to search and apply for jobs, post your resume, research companies, and compare salaries. Every day, we connect millions of people to new opportunities. On our YouTube channel, you’ll find tips and personal stories to help you take the next step in your job search.

The information in this video is provided as a courtesy. Indeed is not a legal advisor and does not guarantee job interviews or offers.

**Comscore, Total Visits, September 2021

***Indeed Internal Data, average monthly unique visitors April – September 2022

Create a free Indeed account: https://go.indeed.com/7NA37Z

Find your next job: https://go.indeed.com/findjobs

More career advice and resources from Indeed: https://go.indeed.com/RFW437

#Indeed #DayInTheLife #FinancialAdvisor

source

Video

INSANE Solo Money Methods in GTA 5 Online (MAKE MILLIONS THIS WEEK!)

Welcome back to another `gta v online` video! Today, we’re diving into the best solo methods to earn `gta online solo money` this week. We’ll show you `how to make money` efficiently in `gta 5` and maximize your earnings with the latest `gta update`. This `gta online` guide covers everything you need to know to get rich!

source

Video

Money Mantra in Telugu #9 | money affirmations #viral #shorts #trending #ytshorts #status #money 1

ATTRACT WEALTH

TELUGU MONEY AFFIRMATIONS

I AM RICH

I AM WEALTHY

MONEY MOTIVATION

MONEY VISUALIZATION

MONEY MANTRA

MONEY POWER

WEALTH MANTRA HYDERABAD

GOLD ATTRACTION

POSITIVE THINKING

RICH LIFE

GRATITUDE

BLESSED

Money affirmations telugu

Money affirmations in telugu

money visualization

money affirmations

very powerful money guided meditation

shorts

positive affirmations telugu

telugu money affirmations

money mantra

dabbu

affirmations for positive thinking telugu

gold affirmations telugu

meditation money mantra

wealth and success affirmations

manasu prashanthanga undalante em cheyali

sarvanand quotes

acharya anantha krishna swamy money affirmations

positive affirmations for wealth and success

daily affirmations for wealth and abundance

self love affirmations in telugu

affirmations for positive thinking telugu

positive affirmations mantra

how to think positive all the time

affirmations for positive thinking telugu

morning affirmations for positive energy in telugu

simple business ideas that make money telugu

high in estment business ideas in telugu

how to earn money business ideas in telugu

how to reprogram your subconscious mind in telugu

subconcious mind affirmations in telugu

subconscious mind video telugu

how to become rich in real life in telugu

how to earn money online telugu

money affirmations in telugu

money comes to me affirmations

only good comes to me affirmations

good things happen to me affirmations

affirmations for money and wealth

morning affirmations for a good day

affirmations for positive thinking

i get things done affirmations

only good things happen to me subliminal

source

Video

Complete Finance MasterClass 2025 | For people in 20’s & 30’s

Notes of this class are available here : https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MZuY6I4Uo66CMSeFhdR4gaNYv3ORNBzS/view?usp=sharing

Time Stamps :

00:00 Capitalism breeds on Insecurity & Isolation

09:44 Real Inflation is 8-10%

18:53 Memorise these Rate & return formulas

21:05 4 Facts to Earn more (in long run)

29:40 5 Steps to spend less

45:22 Equity Stock & MF investment in Detail

1:34:13 Debt Funds in Depth

1:52:37 Real Estate : Rent, Owning & Land

2:17:48 Where to keep our money ?

2:30:53 Major learnings

2:44:08 Understanding Taxes

2:49:21 Bonus learnings & summary

Instagram ❤️:https://www.instagram.com/amandhattarwal/

Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/dhattarwalaman/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/AmanDhattarwal

Want to Work with us? Apply for Job here : https://bit.ly/workWithUs

source

Video

The Drums – Money (Official Audio)

The Drums – Money

Listen to “Money” by The Drums:

Spotify: shorturl.at/npuJU

Apple Music: shorturl.at/lEFJ9

Subscribe to our channel and turn on notifications to stay updated with all new uploads!

Follow The Drums:

Official Site: http://www.thedrums.com/

Spotify: shorturl.at/oxIQU

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pg/wearethedrums/

Twitter: http://twitter.com/thedrumsforever

Instagram: http://instagram.com/thedrumsofficial

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/user/theDrumsForever

TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@thedrumsforever

Get Tickets: https://thedrums.com/shows

#TheDrums #Money

source

Video

MILLI – SHOW ME THE MONEY 12 REACTION | SMTM12 [THAI SUB]

![MILLI - SHOW ME THE MONEY 12 REACTION | SMTM12 [THAI SUB]](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1770943312_maxresdefault.jpg)

🩷 Instagram ➭ https://www.instagram.com/dubbmickey/

🩵 Twitter / X ➭ https://twitter.com/dubbmickey

💚 TikTok ➭ https://www.tiktok.com/@dubbmickey

🐱 Pokémon GO FC ➭ 7596 4773 5651

Support:

💖 Press the “THANKS” button under this video!

🙏 PayPal ➭ https://paypal.me/mickeydubbyt

✨ Patreon ➭ https://www.patreon.com/c/Mickeydubb/

💌 Business Enquiries ➭ mickeydubbyt@gmail.com

⏳ Chapters / ตอน / チャプター

0:00 hello 🙂 / สวัสดี

0:30 video 1 / วิดีโอ 1

4:10 video 2 / วิดีโอ 2

6:15 video 3 / วิดีโอ 3

10:55 video 4 / วิดีโอ 4

11:50 keep smiling 🙂 / ยิ้มเข้าไว้

#MILLI

#ThaiToTheWorld

#YUPP #มิลลิ #TPOP #THAILAND #SMTM12

#MICKEYDUBB

#REACTION

#REACT

สบายดีหรือเปล่า

📌 This video has been created in accordance with the Fair Use Copyright laws both within and outside Australia. All visual and audio content are owned by their respective owners. Commentary provided is solely my personal opinion, and does not represent the views of the associated organisations or artists.

You can learn more about Australian Copyright Law and Fair Use here: https://www.copyright.org.au

source

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoWhy Israel is blocking foreign journalists from entering

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoJD Vance booed as Team USA enters Winter Olympics opening ceremony

-

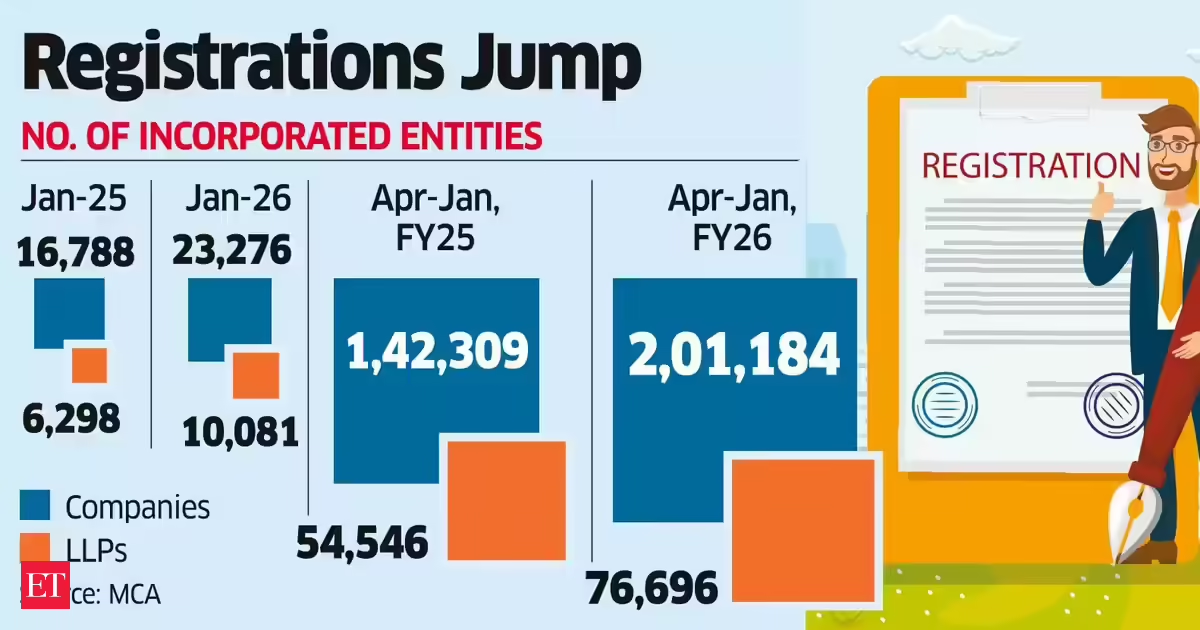

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoLLP registrations cross 10,000 mark for first time in Jan

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoMia Brookes misses out on Winter Olympics medal in snowboard big air

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoFirst multi-coronavirus vaccine enters human testing, built on UW Medicine technology

-

Sports1 day ago

Sports1 day agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoCostco introduces fresh batch of new bakery and frozen foods: report

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

NewsBeat4 days ago

NewsBeat4 days agoWinter Olympics 2026: Team GB’s Mia Brookes through to snowboard big air final, and curling pair beat Italy

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoBenjamin Karl strips clothes celebrating snowboard gold medal at Olympics

-

Sports6 days ago

Former Viking Enters Hall of Fame

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoThe Health Dangers Of Browning Your Food

-

Sports7 days ago

New and Huge Defender Enter Vikings’ Mock Draft Orbit

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoJulius Baer CEO calls for Swiss public register of rogue bankers to protect reputation

-

NewsBeat7 days ago

NewsBeat7 days agoSavannah Guthrie’s mother’s blood was found on porch of home, police confirm as search enters sixth day: Live

-

Crypto World1 day ago

Crypto World1 day agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Video23 hours ago

Video23 hours agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

Crypto World2 days ago

Crypto World2 days agoBlockchain.com wins UK registration nearly four years after abandoning FCA process

-

NewsBeat4 days ago

NewsBeat4 days agoResidents say city high street with ‘boarded up’ shops ‘could be better’

-

Crypto World3 days ago

Crypto World3 days agoU.S. BTC ETFs register back-to-back inflows for first time in a month