Technology

Everything You Need To Know

UPDATE (October 16, 2024): Samsung has started rolling out the October 2024 Android security patch to the Galaxy Z Flip 6. Read more about it at the very end of the article

The Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 arrived in July 2024 during Samsung’s second Unpacked event of the year. The Galaxy Z Fold 6 launched during that event too, and the same goes for some other devices that the company announced. Do note that the Galaxy Z Flip 6 Olympic Edition also arrived (later on). With that in mind, the all-new ‘Flip’ handset is rather similar to last year’s model. Samsung opted not to do a huge revamp of the phone, and that goes for both its design and its internals.

Sure, this one is more powerful, but several aspects that users expected to be upgraded did not get that treatment. The camera hardware remained the same, for example, and that is true for some other internals. Still, this phone has plenty to offer, so let’s get to it. We will first talk about its specifications, and we’ll take it from there.

Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 specs

The Galaxy Z Flip 6 is fueled by the same processor as the Galaxy Z Fold 6. Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 for Galaxy chip fuels the device. That is essentially an overclocked variant of the Snapdragon 8 Gen 3. Samsung opted to include 12GB of LPDDR5X RAM this time around. It also included 256GB or 512GB of non-expandable UFS 4.0 internal storage. The phone includes a 6.7-inch fullHD+ (2640 x 1080) Dynamic AMOLED 2X display. It offers up to 120Hz refresh rate. The cover display measures 3.4 inches and offers a 720 x 748 resolution. That is a Super AMOLED display, though, and it has a 60Hz refresh rate.

A 4,000mAh battery is included here, a slightly larger battery pack than in the Galaxy Z Flip 5. The charging remains the same, however. The phone supports 25W wired, 15W wireless, and 4.5W reverse wireless charging. A charger is not included in the retail box. A 50-megapixel main camera (f/1.8 aperture, OIS, 2x “optical quality zoom”, digital zoom up to 10x) is backed by a 12-megapixel ultrawide snapper (f/2.2 aperture). There is also a camera on the main display, in the form of a hole punch. That is a 10-megapixel camera, by the way.

Android 14 comes pre-installed on the device, along with One UI 6.1.1, Samsung’s Android skin. Bluetooth 5.3 is supported here, while the phone supports dual SIM functionality. The Galaxy Z Flip 6 weighs 187 grams. So, it weighs the same as last year’s model. The device is IP48 certified for water resistance. When unfolded, the device measures 165.1 x 71.9 x 6.9mm. In the folded state, it measures 85.1 x 71.9 x 14.9mm.

How much does the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 cost?

The Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 will set you back $1,099.99 should you choose to buy it. Well, that’s where the pricing starts, that’s the price for the 256GB storage option. The Galaxy Z Flip 5 cost $999.99 for the same model when it launched, so we’re looking at a $100 price bump here.

Are there any deals available?

Samsung did announce some deals for the Galaxy Z Flip 6, initial ones. If you pre-order a carrier version of the device in the US, you’ll get 12 months of Samsung Care+ for free. Also, if you pre-order the device by July 23, you can also get up to $1,000 off with an eligible trade-in, and double the storage from 256GB to 512GB.

In addition to deals from Samsung.com, there are also deals from carriers and retailers. There’s plenty on offer, including great trade-in deals. If you’re interested, check out the links below, and see if any of the deals suit you.

Where can I buy the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6?

You’ll be able to buy the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 at all of the usual places. That goes for both the carriers and the retailers. First and foremost, it’s available directly from Samsung. All major US carriers are offering the device, and you’ll also be able to get it from Amazon, Best Buy, and so on. It will be available in a ton of places. We’ll leave a list of the most popular sources of Galaxy Z Flip 6 availability below.

– Samsung

– Amazon

– Best Buy

– Verizon

– AT&T

– T-Mobile

What carriers does it work on?

The Galaxy Z Flip 6 will actually work on all US carriers. That is something you could have expected. Those carriers are AT&T, T-Mobile, Verizon, and all MVNOs that run on their networks. The Galaxy Z Flip 5 will work just fine on Visible, Metro by T-Mobile, Cricket, US Mobile, and more.

What colors does the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 come in?

Unlike the Samsung Galaxy Z Fold 6, the Galaxy Z Flip 6 comes in seven color variants. So, two more than the Galaxy Z Fold 6. Do note that three of those colors are Samsung.com exclusive, however. The non-exclusive colors are Blue, Mint, Silver Shadow, and Yellow. Those are the colors you’ll be able to get from carriers and retailers. The three exclusive ones are Crafted Black, Peach, and White.

What new upgrades does the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 have over the Galaxy Z Flip 5?

Many of you are probably wondering what are the main selling features of the Galaxy Z Flip 6. Also, what are its advantages over the Galaxy Z Flip 5? Well, the two phones are quite similar (maybe even too similar), so there are not many, but we’ll highlight some features below, read on.

It’s more powerful than its predecessor

The Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 is more powerful than its predecessor. The difference here is not only in the all-new SoC, but the RAM situation too. The Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 for Galaxy fuels this smartphone. That is essentially Qualcomm’s Snapdragon 8 Gen 3 processor, but an overclocked one. In addition to that, however, the phone offers 12GB of LPDDR5X RAM. Its predecessor, the Galaxy Z Flip 5, shipped with 8GB of LPDDR5X RAM.

AI-powered features

The Galaxy Z Flip 6 comes with a bunch of AI-powered features, thanks to Galaxy AI. Suggested replies, for example, analyze your latest messages and suggest tailored responses. That should make the cover display more useful. FlexWindow is another really useful feature that Galaxy Z Flip users are probably familiar with It provides access to Samsung Health updates and notifications, while it also allows you to select the next track you want to listen to. It now offers more widgets than ever, by the way. FlexCam is now more useful too, thanks to Auto Zoom. FlexCam can find the best framing for your shot, and also handle the zooming so that you and all your friends fit in the shot.

Upgraded camera software

Samsung didn’t really move the Galaxy Z Flip 6 forward when it comes to camera hardware. The company is promising camera updates, so the software has been improved, it seems. Samsung says that we’re getting an “upgraded camera experience with clear and crisp details in pictures”. Thanks to AI zoom, you can get up to 10x digital zoom with the main camera.

Better low-light videos

The company is also promising upgrades to video recording in low-light conditions. ‘Nightography’ has been enhanced with video HDR. Samsung did not elaborate anymore, though. The company did say that night mode is now available in-app on Instagram Story, however.

The hinge has been improved

The hinge on the Galaxy Z Flip 6 feels better to use compared to the Galaxy Z Flip 5. In what way? Well, it’s kind of stiffer, and gives off more confidence while you’re using it. Using the phone in a half-closed format will also make more sense thanks to this.

7 years of software updates

Samsung has promised 7 years of OS and security updates for the Galaxy Z Flip 6. The company basically did the same thing Google did for the Google Pixel 8 series. Those are great news for consumers, of course. Samsung is also very timely with its updates lately.

The display crease is better, but not great

The Galaxy Z Flip 5 was notorious for its very noticeable display crease. Samsung has made a move in the right direction when that is concerned, but still… things could be better. Some other, competing devices offer a less noticeable crease than the Galaxy Z Flip 5.

What cases are available for the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6?

In case you’re planning to get the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6, chances are you’ll need a case to put it in. Well, Samsung did list 5 cases on its website, along with a screen protector for the cover display. We’ll go over them below, where you’ll also find links for purchasing them. Do note that all of this comes from Samsung’s US website, the pricing and offerings in other markets may vary.

Clear Case

The Clear Case for the Galaxy Z Flip 6 is the basic silicone see-through case. It offers solid protection, and has a ring on the back, which you can use to grip the phone, or attach it to your belt or something like that. This case is priced at $29.99 at launch ($10 off).

Kindsuit Case

The Kindsuit Case is a case made out of vegan leather aka eco leather. It comes in three colors, Gray, Mint, and Yellow. It will set you back $74.99 ($25 off), should you choose to buy it. This is a special launch offer.

Flipsuit Case with LED

The Flipsuit Case with LED is arguably the most fun case out of the bunch. This case matches your screen and provides cool animations. It’s interactive. The LEDs on the Flipsuit card also light up and sparkle. The Flipcuit Case with LED is priced at $44.99 ($15 off) at the moment.

Flipsuit Case

The Flipsuit Case is basically the same as the case above it, but it does not include the LED aspect. This case has the same price tag as the one above, at launch it costs $44.99 ($15 off).

Slim Clear Case

The Slim Clear Case is the thinnest case Samsung has to offer. Still, this case offers all around protection for the device. Its standard price is $24.99, but at launch, it costs $12.49.

Silicone Case

![]()

The Silicone Case is very similar to the Clear Case, but it’s not see-through, it comes in several colors. The ring on the back is still here, though. It comes in Blue, Navy, Mint, Yellow, and Gray colors. This case’s standard price is $39.99, but at launch, it costs $29.99.

Anti Reflective Film

The last item on this list is a screen protector… for the phone’s cover display. It’s called the Anti Reflective Film, and it’s priced at $22.49 at launch ($7.50 off).

Third-party cases

In addition to all the first-party cases that Samsung announced, there are quite a few third-party options. UAG, OtterBox, Latercase, Thinborne, and many others shared their very own takes on Galaxy Z Flip 6 cases. If you’re interested in any of them simply visit the links provided in the previous sentence.

Should I buy the Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6?

If you’re wondering whether you should buy the Galaxy Z Flip 6, well, that’s always your decision. We can only try and help a bit. The Galaxy Z Flip 6 is quite similar to its predecessor. Samsung didn’t really differentiate this phone enough to warrant an upgrade from the Galaxy Z Flip 5. It has the same charging speed, a very similar design, and so on. It is, however, more powerful, of course. The Galaxy Z Flip 6 is still a very compelling purchase in the general sense, though. It has less competition than the Galaxy Z Fold 6, but still, there are some compelling options. If you’d like to know more about the device’s actual performance, check out our Galaxy Z Flip 6 review.

Updated August 26, 2024:

Samsung has started rolling out the very first update to the Galaxy Z Flip 6. This update does include the August 2024 Android security patch. It fixes 50 major security problems, both Android OS ones, and One UI ones. There are no new features included with this update, unfortunately. It is worth noting that the update has started rolling out in South Korea, Samsung’s homeland. However, it is spreading to other markets as we speak.

Updated September 24, 2024:

The Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 is now receiving the September 2024 security patch. The rollout started in the US, but it spread to a ton of other markets by now. It is rolling out in stages, though, so if you haven’t received it yet, which is highly unlikely, it’s coming soon. This update weighs around 400MB, it all depends on the market. It brings fixes for 67 security vulnerabilities. 44 of those are for Android OS, while the remaining 23 are for Samsung’s One UI skin.

Updated October 16, 2024:

The Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 6 is now getting the October 2024 Android security patch. This update fixes over 30 vulnerabilities in Android and One UI. Do note that the rollout of this update is staged, so it may take a while before it reaches your device. It also didn’t initially launch in all countries, but at this point it’s quite widespread. If you didn’t get the update it will land soon. There are no new features included here, only security improvements.

Technology

T-Mobile to launch 5G-advanced service by end of 2024

T-Mobile is gearing up to launch its first 5G-Advanced service by the end of 2024, according to the carrier’s president of technology, Ulf Ewaldsson. The announcement came during Ewaldsson’s conversation with Fierce Wireless at the Mobile World Congress. The upgrade will provide faster speeds, enhanced video streaming, and improved network capabilities.

T-Mobile 5G-Advanced Coming by Year-End

Ewaldsson revealed that T-Mobile’s 5G-Advanced service will be a software upgrade to its existing 5G standalone (SA) network. This advancement is based on the 3GPP Release 18 5G-Advanced specification. T-Mobile plans to roll out the technology by the end of this year, focusing on more efficient spectrum use and precise location capabilities.

“It’ll be at the end of the year. We’re going to be introducing a technology called L4S. It’s a video priority technology that creates a better video experience for different applications,” Ewaldsson said.

The upgrade positions T-Mobile ahead of its competitors, thanks to its nationwide pure 5G SA network. Unlike other smartphone carriers, who still depend on 4G LTE cores for their 5G networks, the company’s SA deployment offers a significant advantage in adopting the latest 5G technologies.

The new 5G-Advanced service will include features like enhanced spectral efficiency and improved positioning. This update will also introduce L4S (Low Latency, Low Loss, Scalable) throughput technology, which is expected to elevate video streaming quality on the network. L4S technology enables the network to adapt video bit rates based on current conditions, ensuring a smoother experience during times of high demand.

T-Mobile has already started integrating other advanced features into its 5G SA network, such as voice-over-New Radio (VoNR) and network slicing. These developments, along with the upcoming 5G-Advanced service, highlight T-Mobile’s commitment to staying at the forefront of 5G technology.

Competitive Edge in 5G-Advanced Rollout

While T-Mobile continues to expand its 5G capabilities, other major carriers like AT&T and Verizon have also begun to implement standalone 5G technology. However, they have not yet achieved the nationwide reach that T-Mobile has.

Technology

Amazon’s new Kindle Paperwhite reader has a larger screen and faster page turns

Amazon’s latest version of its popular Kindle Paperwhite has arrived, marking the sixth iteration if you’re keeping score at home. The new model is the thinnest Paperwhite yet and has a refreshed 7-inch screen that’s a touch larger than the previous model’s 6.8-inch display. It also has the highest contrast of any Kindle thanks to the oxide thin-film transistor display tech.

Amazon boosted the speed as well, promising 25 percent faster page turns. It’s waterproof as before but uses a new material with a premium soft touch grip. The Kindle Paperwhite comes with 16 GB of storage and is available in three colors, Raspberry, Jade and Black. It’s now available at Amazon for $160.

As before, the company also released a premium version with more bells and whistles, the Paperwhite Signature Editing. Storage doubles on that model to 32 GB and it features an auto-adjusting front light along with optional wireless charging. The Paperwhite Signature Edition comes in Metallic Raspberry, Metallic Jade and Metallic Black for $200.

If it’s a budget reader you’re after, Amazon has refreshed the entry-level Kindle, too. The new 12th-generation model comes with an updated 6-inch screen, offering a higher contrast ratio for more legible text, plus a front light that’s 25 percent brighter at the maximum setting. It also gets a performance update that boosts page turning speeds. It comes in black or a new “Matcha” color and is now on sale for $110.

Along with those models, Amazon also unveiled its first color Kindle, the Colorsoft, that could be ideal for graphic novels and other digital color-oriented content. It promises “rich, paper-like color” using an oxide backplane display, plus high contrast on both color and black-and-white content. It’s now on pre-order for $280 with shipping set for October 30th. Finally, Amazon is releasing its second Kindle Scribe reader that doubles as a note-taking device (not unlike the reMarkable tablets). It’ll arrive on December 4, but you can pre-order it now for $400.

Technology

Play unveils Build Play development platform for Web3 games

Play, formerly known as ReadyGG, has launched the Build Play development platform to expand access to Web3 technologies for gaming.Read More

Technology

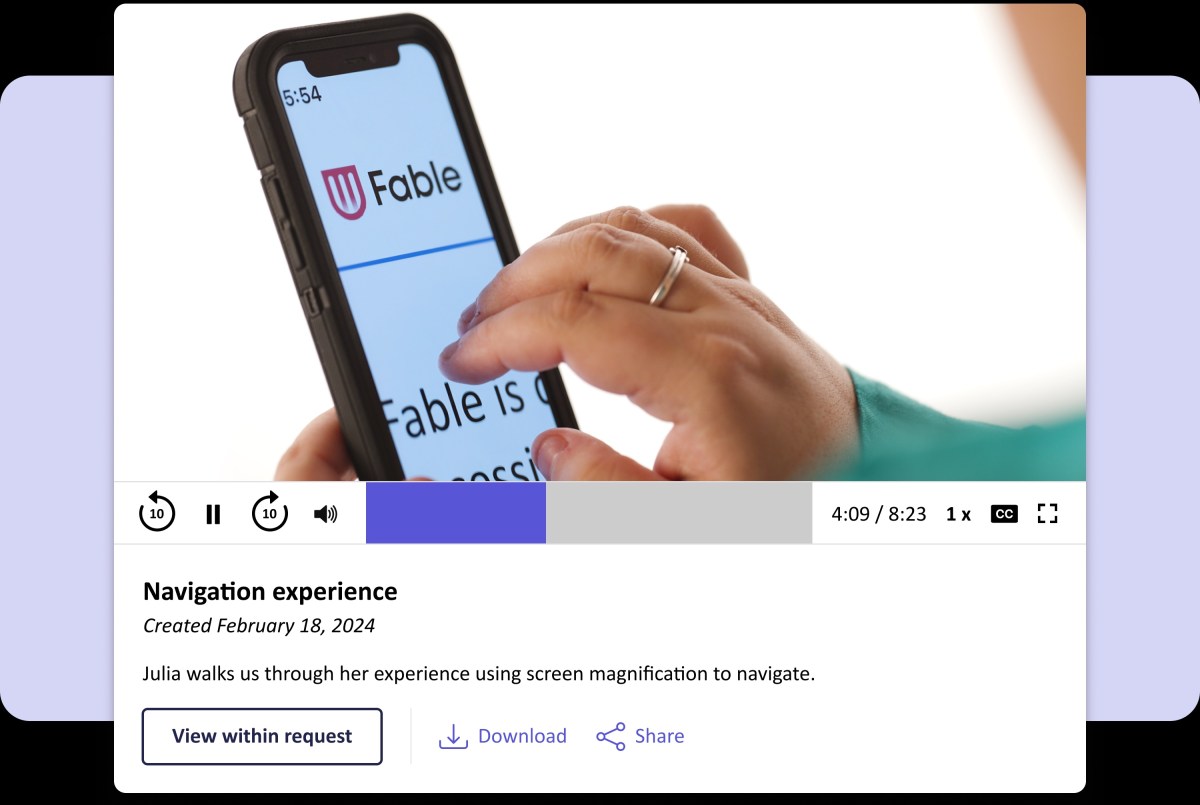

Fable adds cognitive and hearing impairments to its accessibility tools with $25M round

Fable has gained a reputation as the go-to startup for helping companies build digital products that are more accessible to people with disabilities. After raising $25 million in new funding, the Toronto-based startup is now expanding the communities it supports and working to make AI training data more inclusive.

Fable started in 2020 as a way to consult more easily with accessibility experts and people with disabilities, so anyone building a product could have the best advice on making it as accessible as possible. Since its A round two years later, it has been building out a more robust product offering, with content, testing, and tools that integrate more directly with developers’ workflows.

“Accessibility is no longer just the responsibility of the accessibility specialists or product managers — it’s shifting to everyone in the product development process: researchers, designers, product managers, engineers,” said CEO and co-founder Alwar Pillai in an interview with TechCrunch. “It’s historically been another group that’s been responsible for it and doing the work. Now they’re taking that shared accountability and responsibility, and Fable is a platform that’s allowing them to do it by themselves.”

Companies building and maintaining large platforms have come to accept to the fact that you can’t sprinkle accessibility on at the very end like Salt Bae. It has to be baked in from the start — and making the product better for people with disabilities usually makes it better for everyone else, too.

Fable initially supported vision and motor disabilities to get a warm start, Pillai explained:

“We wanted to find a way just to get companies comfortable with engaging with this population, because it has historically been excluded, and these were communities that organizations are a bit more familiar with. over the course of time, we’ve observed a couple of trends within our customer base that made it like this is the right time for us to expand our community to represent people with cognitive disabilities and with hearing disabilities.”

One in six people has some form of disability, she noted, though not all are visible or even something a person may mention. There are lots of assumptions built into user experiences, about what a user can see, hear, do, and understand. Finding and improving them is not always easy if you don’t have, say, a deaf person or someone with dyslexia on your testing team.

“If you get the insights from these communities, you are going to, at the end, make products that work well for everyone. But it has been historically challenging for enterprises to engage with this community easily, and on demand. And that’s when Fable jumps in,” she said.

Over the years, Fable has built out assessment tools as well as advisory ones, so product managers and engineers can track accessibility the way they do other standard function and quality milestones.

A new area of tech that deserves special attention, and which Fable is hoping to improve, is the data powering AI models. Bias in data translates to bias in models, and that’s as true for people with disabilities as it is for other categories.

One reason for this is that these AI models tend to aim for the most aggressively average answer or response — dead center on the bell curve. But people with disabilities tend to fall outside that average need or experience.

“We’re excited and cautious about the proliferation of AI; there’s a huge opportunity to make experiences better for people with disabilities,” said Pillai. “But at the same time, it also has the ability to amplify the digital divide that exists. We’re seeing AI getting baked into so many things, but because people with disabilities have not been taken into account there, and the data that you probably collect is smaller, so they get excluded from the large models, we think they have the ability to exclude the experiences of people with disabilities because it deviates from the ‘normal.’ “

This can be mitigated with fine-tuning or prompt engineering, but only so much; a model necessarily pulls from the datasets it’s trained on, so if disabilities are not adequately represented in there — and they aren’t — the models simply are not equipped for accessibility. Fable has been working with the community, as well as researchers and governments, to create resources and best practices.

“Our goal is that, in the near future, we’re able to introduce these inclusive data sets and offer testing for accessibility in AI. Our customers are already coming to us for it,” Pillai said.

She emphasized that, as before, it’s about empowerment to include these methods in a company’s own development processes — Fable doesn’t do the work for them.

“Our platform now has become this dashboard where you can monitor all of your digital properties and products against these accessibility metrics. We invested in integrations, because we wanted the insights and data to live in the products that product teams are using on a daily basis,” Pillai said. “We’ve gone from just being able to get one piece of insight to really being able to observe your performance across products, and when you think about enterprises, they have, like, 500-plus digital products. The goal for them is, how do I know if I’m getting better or not? And finally, they have metrics to prove it.”

The $25 million B round, led by Five Elms Capital, will be put towards standing up the new teams and products around cognitive and hearing impairments, and of course AI expertise as well. Pillai said that, while the investment climate isn’t as open as it was a few years ago, they were pleasantly surprised while they were raising.

“It was so different from the last few times we raised,” Pillai recalled. “I remember when we raised our seed and series A it was very much, you know, trying to convince investors about the opportunity around the accessibility space. But this time around, investors had a very strong understanding of the space, the growth opportunity. It was more about, you know, how much value are you adding to customers, and how are you growing? I think that stood out.”

Science & Environment

Amazon goes nuclear, to invest more than $500 million to develop small module reactors

Amazon Web Services is investing over $500 million in nuclear power, announcing three projects from Virginia to Washington State. AWS, Amazon‘s subsidiary in cloud computing, has a massive and increasing need for clean energy as it expands its services into generative AI. It’s also a part of Amazon’s path to net-zero carbon emissions.

AWS announced it has signed an agreement with Dominion Energy, Virginia’s utility company, to explore the development of a small module nuclear reactor, or SMR, near Dominion’s existing North Anna nuclear power station. Nuclear reactors produce no carbon emissions.

An SMR is an advanced type of nuclear reactor with a smaller footprint that allows it to be built closer to the grid. They also have faster build times than traditional reactors, allowing them to come online sooner.

Amazon is the latest large tech company to buy into nuclear power to fuel the growing demands from data centers. Earlier this week, Google announced it will purchase power from SMR developer Kairos Power. Constellation Energy is restarting Three Mile Island to power Microsoft data centers.

“We see the need for gigawatts of power in the coming years, and there’s not going to be enough wind and solar projects to be able to meet the needs, and so nuclear is a great opportunity,” said Matthew Garman, CEO of AWS. “Also, the technology is really advancing to a place with SMRs where there’s going to be a new technology that’s going to be safe and that’s going to be easy to manufacture in a much smaller form.”

Virginia is home to nearly half of all the data centers in the U.S., with one area in Northern Virginia dubbed Data Center Alley, the bulk of which is in Loudon County. An estimated 70% of the world’s internet traffic travels through Data Center Alley each day.

Dominion serves roughly 3,500 megawatts from 452 data centers across its service territory in Virginia. About 70% is in Data Center Alley. A single data center typically demands about 30 megawatts or greater, according to Dominion Energy. Bob Blue, its president and CEO, said in a recent quarterly earnings call that the utility now receives individual requests for 60 megawatts to 90 megawatts or greater. Dominion projects that power demand will increase by 85% over the next 15 years. AWS expects the new SMRs to bring at least 300 megawatts of power to the Virginia region.

“Small modular nuclear reactors will play a critical role in positioning Virginia as a leading nuclear innovation hub,” said Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin in a release. “Amazon Web Services’ commitment to this technology and their partnership with Dominion is a significant step forward to meet the future power needs of a growing Virginia.”

AWS plans to invest $35 billion by 2040 to establish multiple data center campuses across Virginia, according to an announcement from Youngkin last year.

“These SMRs will be powering directly into the grid, so they’ll go to power everything, part of that is the data centers, but everything that is plugged into the grid will benefit,” Garman added.

Amazon also announced a new agreement with utility company Energy Northwest, a consortium of state public utilities, to fund the development, licensing and construction of four SMRs in Washington State. The reactors will be built, owned and operated by Energy Northwest but will provide energy directly to the grid, which will also help power Amazon operations.

Under the agreement, Amazon will have the right to purchase electricity from the first four modules. Energy Northwest has the option to build up to eight additional modules. That power would also be available to Amazon and Northwest utilities to power homes and businesses.

The SMRs will be developed with technology from Maryland-based X-energy, a developer of SMRs and fuel. Along with Amazon’s other announcements, Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund disclosed it is the lead anchor in a $500 million financing round for X-Energy. The Climate Pledge Fund is its corporate venture capital fund that invests in early-stage sustainability companies. Other investors include Citadel Founder and CEO Ken Griffin, affiliates of Ares Management Corporation, NGP and the University of Michigan.

“Amazon and X-energy are poised to define the future of advanced nuclear energy in the commercial marketplace,” said X-energy CEO J. Clay Sell. “To fully realize the opportunities available through artificial intelligence, we must bring clean, safe, and reliable electrons onto the grid with proven technologies that can scale and grow with demand.”

Last spring, AWS invested in a nuclear energy project with Talen Energy, signing an agreement to purchase nuclear power from the company’s existing Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, a nuclear power station in Salem Township, Pennsylvania. AWS also purchased the adjacent, nuclear-powered data center campus from Talen for $650 million.

Technology

How Grokster’s music piracy case changed the course of the internet forever

By the time MGM v. Grokster hit the Supreme Court, the file-sharing industry had been roiling with lawsuits for years. The record labels had sued Napster in December 1999, baptizing the oughties with a spree of copyright litigation. But the public’s appetite for piracy didn’t go away, and for every Napster that was sued into oblivion, three more sprung up in its place. Their names are now commemorated only in the court decisions that eventually destroyed them: Aimster, StreamCast, and of course, Grokster.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the Grokster case in December 2004, and oral arguments took place in March of the following year. The copyright wars had finally arrived before the justices. The court heard first from Don Verrilli, the attorney representing a bevy of movie studios and record labels belonging to the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry of America, respectively. “Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court: copyright infringement is the only commercially significant use of the Grokster and StreamCast services, and that is no accident.”

The first interruption came halfway into Verrilli’s next sentence, and the volley of questions continued before this case about peer-to-peer file sharing took a sharp turn into what, to a total outsider, might have seemed like an off-beat question: What’s the difference between file sharing and the Xerox machine?

But for those following the case from inception, this was, in fact, the Big Question. When copyright law and the internet collide, new technologies are inevitably compared to old technologies in a mix of gut-check and devil’s advocacy. A Xerox enables copying — often of copyrighted works! — on a mass scale. So do the VCR and the iPod. “Are you sure that you could recommend to the iPod inventor that he could go ahead and have an iPod or, for that matter, Gutenberg, the press?” Justice Stephen Breyer asked Verrilli. And then, in one of those mischievous asides that he was known for, Breyer added, “For all I know, the monks had a fit when Gutenberg made his press.” (The audience tittered in polite, pandering laughter.)

The iPod would come up again and again throughout oral arguments. Though portable MP3 players had been around for a while, Apple’s version had taken the world by storm, in part because of its sleek design and high capacity and in part because it was conveniently linked to the iTunes Store, a legitimate system for buying music digitally. Yet, the hard drive space was a nod to the enormous digital libraries people could potentially acquire — or even had already accrued — through piracy.

And they didn’t mince around what was happening across the country. “I know perfectly well I could go out and buy a CD and put it on my iPod,” said Justice David Souter. “But I also know perfectly well that if I can get the music on the iPod without buying the CD, that’s what I’m going to do.” If that was the case, and the RIAA got its way, wouldn’t the threat of copyright litigation be hanging over some future Steve Jobs or Jony Ive?

“I don’t actually think that there is evidence that you’ve got overwhelming infringing use,” Verrilli began to reply. Sure, people were using the iPod to infringe copyright, but it wasn’t with the same consistency as for a file-sharing client, right? But before Verrilli could finish that train of thought, Souter interrupted again.

“Well, there’s never evidence at the time the guy is sitting in the garage figuring out whether to invent the iPod or not.”

There was an implicit assumption on all sides that the iPod was legal, that the iPod was legitimate, that the iPod was worth protecting. The justices fretted that letting the file-sharing services win would destroy the music industry; but on the other hand, if they let the MPAA and RIAA win, it would destroy the iPod.

Meanwhile, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a known copyright maximalist, reserved her gotchas for the other side, lobbing them straight at Richard G. Taranto, who was representing the file-sharing companies. “You don’t question that this service does facilitate copying.”

“As does the personal computer and the modem and the internet service provider and the Microsoft operating system,” Taranto replied smoothly.

That is, of course, more or less the rub: if the Xerox machine is somewhat of a troubling invention, everything about our modern-day computer-rich ecosystem is a thousand times worse. My phone syncs to my tablet, syncs to my laptop; the value proposition of every device on my person is that it instantaneously and unquestioningly shares copies — of text, pictures, audio, video — with other devices and other people. A website is a thousand, million, billion copies served up to different people at different times. Copies are downloaded to devices, uploaded to servers, linger, and then vanish again while in transit. There is a fundamental mismatch between the post-internet era and the very foundation of copyright law, and a hundred strange little tweaks and twists and exceptions have had to be made to make square pegs fit into round holes.

Grokster is the story of one of those exceptions.

The Supreme Court would ultimately decide Grokster in favor of Hollywood and the record labels, but without fully adopting their reasoning. And in the court’s strenuous efforts to walk that fine line between the iPod and the RIAA, it shamelessly made up an entire copyright law doctrine without batting an eye, a theory of liability that hadn’t existed up until that point in time.

Copyright law had been one thing in 2004. It was a completely different thing in 2005 and beyond.

In all fairness to the Supreme Court of 2004, it had waded into the legal version of a forum flame war. In every courtroom, lawyers act out hostilities as a form of theater. But for some reason, the copyright wars really were as hostile as they seemed on the outside.

“I would say there was really a battle going on between Hollywood and Silicon Valley,” recalled Mark Lemley, a law professor at Stanford and longtime litigator who, in 2003, won the Grokster case in the lower court. “And you saw it in lots of different places.”

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) had been passed only a few years prior. For tech industry lawyers and internet freedom types at the time, the passage of the DMCA — with its legal restrictions on bypassing DRM and its loophole-riddled safe harbor regime which allowed platforms to evade liability for hosting copyrighted material so long as they took it down upon notice — was a crushing defeat. The file-sharing lawsuits were part of the same war, merely fought on different grounds.

“I think each side really did think that this was existential, that the other side is going to destroy us,” said Lemley. “One side said, ‘The copyright industry wants to eliminate digital technologies,’ and the copyright industry said, ‘We’re not going to survive, creativity is not going to survive, if everybody could just get this stuff for free.’ And so everybody felt like this was it, right? This was for all the marbles.”

The record labels had sued the makers of the Rio MP3 player in RIAA v. Diamond and had lost. The Diamond decision even contains a few lines that suggest that it’s fair use to rip a store-bought CD into a digital format. (Believe it or not, that’s something that has still never been definitively settled in a court of law, although Justice Souter got the RIAA’s Verrilli to say it was fine during the Grokster oral arguments at the Supreme Court.)

The RIAA’s lawyers were mostly winning their battles against the peer-to-peer file-sharing services, but they were losing the war. The hottest new gadgets were riding on the back of music piracy, and the better that computers and internet speeds got, the easier piracy became. Successive iterations on Napster emerged — some were tech companies backed by venture capital; others, like the Pirate Bay, founded in 2003, were practically ideological.

People simply would not stop pirating music. The industry’s next move reeked of desperation: in 2003, the labels moved on to suing individual downloaders.

The idea was to scare people straight, but in many respects, this was a disastrous strategy. The PR fallout was enormous. Unable to perfectly identify defendants based on their IP addresses, the RIAA’s hit rate was, to say the least, extremely problematic. Parents were being sued for what their underage kids had done on the family computer. Stories about little old grandmas getting lawsuits mistakenly thrown at them were ubiquitous in the headlines. Even the artists that publicly backed the RIAA suits — like Metallica — were roundly mocked and despised by their own fans for doing so.

The labels, on some level, had to know that it was not the best idea. After all, they only resorted to suing normal people after they tried suing file-sharing services and MP3 player manufacturers. These people, depending on your angle, might be called users, pirates, fans, or downloaders. They were often young teenagers; when they weren’t minors, they were frequently college students who had, after moving into their dormitories, accessed high-speed internet for the first time. In the court of public opinion, these kids were collateral damage in the copyright war between “the tech industry” and “the content industry.” But in a court of law, the kids were the real perps in a multibillion-dollar crisis of copyright infringement.

The file-sharing services were technology companies, and the technology on its own was not illegal. The peer-to-peer file-sharing services were selling software; they weren’t even hosting the content. And the newest generation of services weren’t hosting a central database to search for content, the way that Napster did.

All sorts of new tech — like VCRs and Xerox machines — have undergone periods of copyright anxiety before coming out the other side. They became established as legitimate innovations that sometimes get used for copyright infringement. In fact, in the case of the VCR, a seminal 1984 Supreme Court decision had smoothed things along.

The RIAA might have defeated Napster in court, but the recording industry’s case was never ironclad. Each new iteration on Napster became another opportunity to hash the principle out in court. To what degree could the technology be held liable for the copyright infringement of the users? It was only a matter of time before someone showed up and finally scored a win against the labels.

When the Grokster and StreamCast cases went up on appeal together, it was Fred von Lohmann of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a persistent thorn in the side of the RIAA, who argued them before the Ninth Circuit. The appeals court gave the win to the file-sharing services; shortly after, in December 2004, the Supreme Court granted certiorari, agreeing to hear the case.

Lemley remembered feeling both nervous and cautiously optimistic. The Ninth Circuit had made a well-reasoned and articulate extrapolation from Sony v. Universal City Studios, the 1984 Supreme Court case lawyers often refer to simply as “Betamax,” since both Sony and Universal are frequent fliers in the legal system. The case established that Sony itself was not infringing copyright by selling VCRs, even though many VCR owners were copying television programs at home. Sony’s Betamax tapes might be remembered as the also-ran format of VHS, but its name lived on in this legal precedent two decades later.

Beyond that, said Lemley, even if almost all the content on Napster was copyright infringement, that wasn’t necessarily the case in Grokster. The plaintiffs who had filed suit in the Grokster and StreamCast cases represented more or less every record label and motion picture studio in America. When lined up one after another, their names sprawl across multiple pages of the frontispiece of the Ninth Circuit decision. Still, they had only been able to allege that 70 percent of the content being shared on these services belonged to them, though they estimated that 90 percent infringed someone’s copyright.

And that mattered. Ten percent, said Lemley, should be enough to support the idea that Grokster had “substantial non-infringing uses,” which was the legal standard set in the Betamax case. A footnote in the Betamax decision even suggests that it was enough that 7.3 percent of the time, consumers were not violating copyright law.

7.3 percent? That was barely anything. The file-sharing services had a whopping 10 percent going for them.

Still, said Lemley, there was also good reason to be nervous. The procedural background was slightly alarming (for the Supreme Court aficionados: when the court granted cert, there was, at most, a “shallow circuit split” in the case; arguably, there was no split at all). And the case was coming out of the Ninth Circuit, an appellate court that SCOTUS notoriously loves to reverse.

The Supreme Court, too, is just a different animal altogether. Theoretically, SCOTUS is only a notch above the federal appeals courts. But that single ladder rung separates the rest of the legal system with a moat of bizarre customs, foibles, and etiquettes. The bar of attorneys admitted to practice in the Supreme Court is an exclusive one, and within that bar is an even more exclusive group of people who regularly argue in front of it, an elite priesthood that panders to nine robed gods on a raised dais in a theatrically lit room.

The file-sharing companies did not have the deep pockets for one of these private sector big guns, and so their EFF lawyer Lohmann was slated to argue the case before the justices. But in the end, billionaire Mark Cuban ponied up the cash to pay for Richard Taranto, who had been arguing in front of that court for 20 years. (“I did it because I thought the music industry was being heavy handed with IP and Grokster was the underdog,” Cuban wrote The Verge in an email. “Beyond that I don’t remember anything.”)

“I’ll admit I was a little bit disappointed,” said von Lohmann. But going with the specialist — now that there was money to pay him — made sense. “Basically, arguing in front of the Supreme Court is like being a therapist to those nine people. It’s not just about the law. It’s also about knowing what the justices’ pet hobby horses are and what things trigger them and what their alliances and animosities are.”

And von Lohmann, an early adopter and internet nerd who had fallen in love with digital copyright law after reading an article in an early issue of Wired, was not quite the vibe for this scene. The day that Grokster was heard in the Supreme Court was a momentous one — in addition to changing copyright law forever, the oral argument right before Grokster was for Brand X, the case on which modern-day net neutrality rests.

Yet, on that day, the press gallery was abuzz, fixated on something else: Fred von Lohmann had a ponytail. No one could remember another time that a male lawyer with long hair had shown up in front of the justices.

The Ninth Circuit, where von Lohmann had argued and won the case before it came to the Supreme Court, had not cared about his ponytail.

But von Lohmann would hear about all that later. In the moment, he was focused on what he thought was the moment that the internet was going to get a clear rule. The Ninth Circuit had interpreted Betamax to protect the file-sharing companies. The RIAA and MPAA were never going to leave that precedent alone; the technology industry and the EFF and Mark Cuban, too, were not going to leave this issue alone, either. No matter who won or lost, the Supreme Court had to settle the principle once and for all.

Except it didn’t. “In some ways, it’s so disappointing that the Supreme Court did not give us an answer,” said von Lohmann. “Rather than deciding ‘Is Betamax still the foundation of the technology sector?’ they sort of punted that question and answered a different question.”

Grokster is a strange SCOTUS precedent because honestly, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. The decision created a new form of liability known as “inducement”: the technology companies, the court ruled, had seduced the users — the teens, the kids, the fans, the pirates — into infringing copyright. It didn’t matter that these services never hosted any files or made a central index.

Some of the evidence the court cites is kind of weird. For instance, StreamCast had distributed a program called “OpenNap” and had run ads for it with Napster-compatible programs. Grokster had it even worse — the connection to Napster was in its own damn name! “[A]nyone whose Napster or free file-sharing searches turned up a link to Grokster would have understood Grokster to be offering the same file-sharing ability as Napster; that would also have been the understanding of anyone offered Grokster’s suggestively named Swaptor software, its version of OpenNap,” read the SCOTUS opinion.

The primary takeaway of Grokster is “don’t look like Napster,” written in such vague terms that liability seems to loom over much of the tech industry. Okay, so, don’t start a company with a name ending in -ster. But now what? Who would be deemed the next Napster? How do you avoid looking like them? How do you even know what the next Napster is? What does it mean to not look like you’re courting customers who may or may not infringe copyright? A device that streams TV broadcasts to your laptop, a website for uploading mix tracks, an image host that markets itself as dedicated to memes and viral content — where do they stand? The decision didn’t overturn Sony v. Universal, but Betamax was no longer the reliable precedent it once was. “Most honest copyright lawyers would tell you that the value of Betamax in protecting technology vendors has been eroded in the years since Grokster was decided,” said von Lohmann.

Copyright law is deeply punitive. Unlike most other torts, the rights holder doesn’t need to show that they were harmed; the statute allows a judge to levy up to $150,000 in statutory damages per infringed work. (That’s in extreme, “willful” cases, as the recording industry believed Napster was. In normal cases, statutory damages are supposed to range from $750 to $30,000 per work.) If a user base is consuming millions of songs or movies or pictures via a service, that’s more money than most national GDPs. In practice, no tech company ever gets hit with a trillion-dollar copyright judgment, but the theoretical risk is still enough to give pause.

In its immediate wake, Grokster seemed to hang over the industry like a sword. It came as a particular shock to Lemley, who had sailed away on a vacation to the Arctic Circle with no satellite service just hours before the Supreme Court decision came down — two weeks later, he became the last of the lawyers in the suit to find out what had happened to his case.

“I don’t think Grokster made file sharing go away,” said Lemley. “But I do think it changed the legal landscape and made it more challenging to be a high-profile tech company that was in the business of digital content transmission. I think a bunch of folks just went out of business.”

Ultimately, Grokster would shut down in 2005; StreamCast Networks filed for bankruptcy in 2008.

The public’s perception of downloading, too, made a radical shift. “The legal campaign, the lawsuits against individuals, the media coverage — the cases actually made change,” said von Lohmann. Until the RIAA launched what seemed at the time to be a futile war against piracy, nobody took individual piracy seriously. “When I was a kid, like, nobody ever thought twice about, ‘Oh, can I borrow that album? I’ll tape it at home.’”

But he witnessed the shift in attitudes personally while on the front lines of the copyright wars. “During that period, when you did surveys, it became increasingly difficult to actually get a read on how widespread file sharing was because, between 1999 and 2005, everybody started lying about it,” said von Lohmann. It had gone from something uncontroversial to something like smoking weed. Everyone did it. Everyone knew that everyone else did it. Nevertheless, you weren’t supposed to admit it.

Before that shift in public perception, for the true fans, file sharing was just a means that the record labels were not providing. The fans wanted to listen to everything, to have a real choice of favorite artist before buying concert tickets and merch, to be able to consume an entire back catalog. Fans wanted digital music. They wanted easy access to music. They wanted lightweight and portable MP3 players. They also, indisputably, loved free shit. Not every downloader is a fan, and not every fan is circulating money back into the creative economy.

The music industry thought that freeloading tech companies would destroy them, and the tech companies thought that the music industry’s overzealous copyright lawyers would, in turn, destroy them.

But then things just sort of settled down. Steve Jobs introduced the iTunes Music Store in 2003 with explicit comparisons to file-sharing services, and it was already proving its economic potential. Spotify was founded in Sweden the year after the Grokster decision came out. The content industry and the tech industry were no longer in a deathmatch to destroy the other. Licensing was making the money flow again. Beyond that, people now had “a simple and not that expensive way to get music legally,” said Lemley. “And that, I think, causes a bunch of people to just sort of stop using file sharing. It doesn’t go away. But it just becomes, you know, what I wanted, which is the ability to play music on my devices.”

It turned out, as well, that the DMCA — the law that Silicon Valley had seen as a terrible defeat — ended up becoming much more important than anyone had thought it would. The spooky uncertainty of Grokster drove platforms straight into the arms of the DMCA safe harbor provision, which kept the copyright lawyers away so long as they were given bureaucratic systems which allowed notices of infringement to be sent and content to be taken down. Over the next few years, the case law and precedents around the DMCA would accumulate into a robust body of law through which much of the internet survived and even thrived. The world we currently inhabit, in which your Instagram posts get flagged, your favorite Twitch streamers get temporarily banned, and every YouTuber understands that a copyright strike is a nuclear weapon, is one that came to life after 2004.

Relations have since thawed between the tech industry and the content industry — if relations are not exactly amicable, they are, at least, inflected with a sense of normalcy.

Consider how much the issue of AI and copyright continues to inflame the public imagination, and yet, rather than launching a unified war, some media companies have sued, while other media companies — including The Verge’s parent company Vox Media — have chosen to simply cut deals with the likes of OpenAI. Copyright is not a crusade; copyright is business as usual.

For many readers, this is all a nostalgic backdrop to a story they may or may not have heard in some iteration or another. And yet, a not-insignificant number of people are reading these words in the year 2024 and scratching their heads.

“In an era where we all just take Spotify for granted, people don’t remember what it was like when every CD cost you like 10 dollars,” said Fred von Lohmann. “Your personal CD collection was a tiny window on the world of music, like a very carefully selected curated slice of the universe of music. And Napster changed that overnight. And suddenly, you could be like, I can listen to obscure reggae. And then I can listen to electropop, and then I can listen to The Beatles.”

For von Lohmann, the advent of file sharing was akin to the moment The Wizard of Oz goes from black-and-white to color. “I would still argue in some ways, we still don’t have it as good now as fans as we did with Napster in ’99,” said von Lohmann. “There’s still a lot of stuff that you can’t get that was available — like live recordings and rarities and bootlegs and stuff that will never be on Spotify.”

But the difference between now and the 1990s is still stark. Napster and the MP3 players that rode the wave of file sharing — the Rio, the Zen, the iPod — changed everything about how we listen to and relate to music. Digital files are no longer the secondary backups of our physical libraries, an echo of “the real thing” made for convenient transport. Music is digital-first; the vinyls and the CDs are secondary — for many, they are merely mementos. And technology has also changed the economic incentives around music, cratering the revenues generated through the major labels and pushing musicians to seek out alternative revenue sources.

Music, today, is not about copies — it is about streaming. It exists as a choice between platforms — Spotify, Apple Music, and so forth. The number of plays is the coin of the realm.

A song is a vibe, the backdrop of a TikTok, a meme waiting to happen, a copyright bomb that can nuke a livestream. An MP3 is a perplexing fossil. A physical CD is a limited-edition collectible.

Of the nine justices who heard Grokster, only one still sits on the court (Clarence Thomas). Verrilli, who represented the studios and labels, went on to become solicitor general of the United States; today, he is back to arguing Supreme Court cases in the private sector. Taranto, the lawyer that Mark Cuban paid for, sits as an appeals court judge on the Federal Circuit.

After leaving the EFF, Fred von Lohmann went on to work for Google — he would be there during the latter half of the tortuously elongated Google Books copyright litigation, the landmark DMCA precedent set by YouTube’s victory against Viacom in the Second Circuit, and the unending software copyright shitshow that was Oracle v. Google. He is now legal counsel at OpenAI, which is currently besieged with its own thicket of copyright lawsuits; he declined to talk about AI and copyright with me, asking to stick to the topic of a yesteryear long gone by.

Grokster and StreamCast are dead. Even the iPod is no longer in production. They are buried and gone, like the Betamax and the Betamax “substantial non-infringing uses” standard — all relics of a bygone era, the ephemera of 2004. Copyright law barely made sense then. As you might suspect, 20 years later, it makes even less sense now.

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

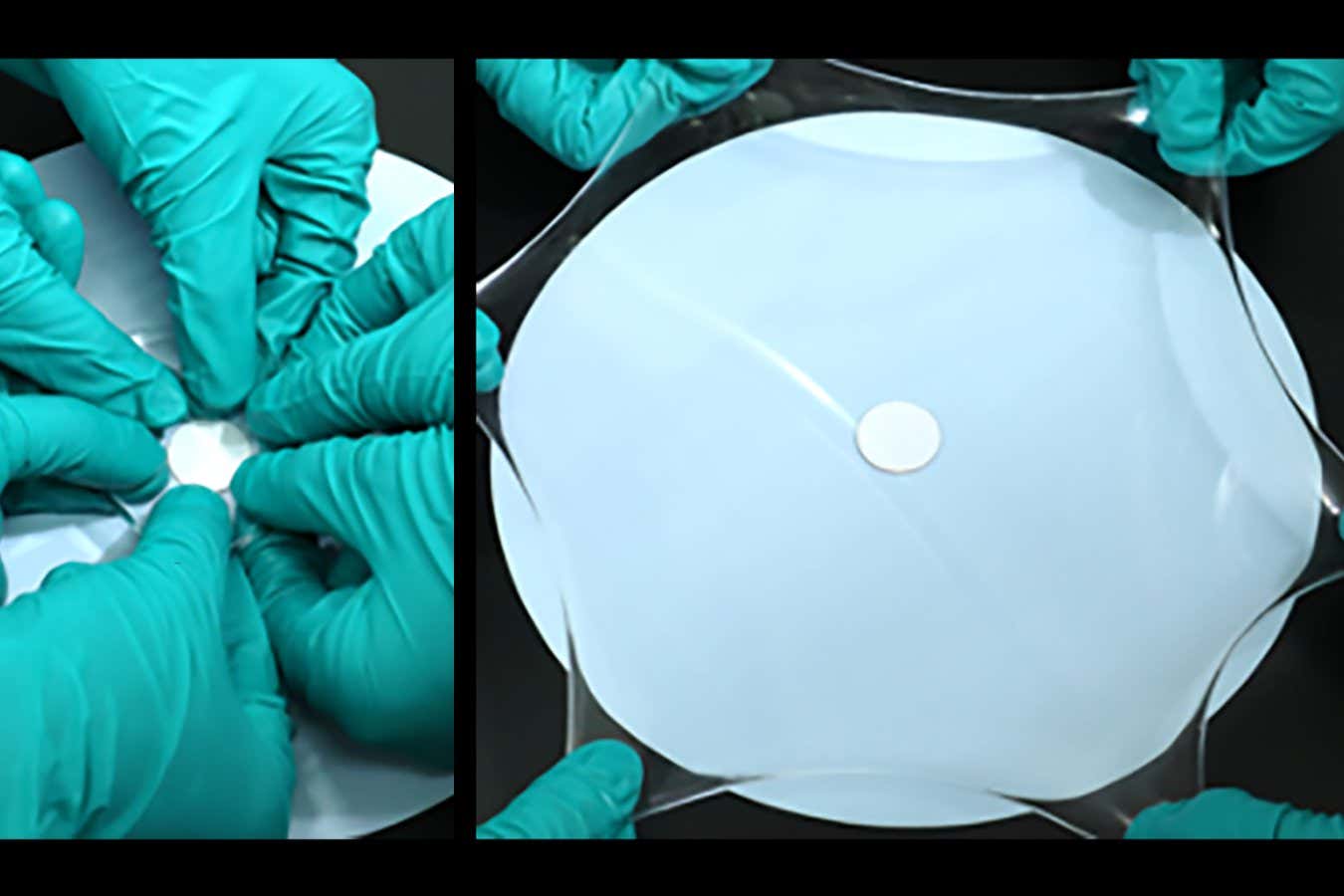

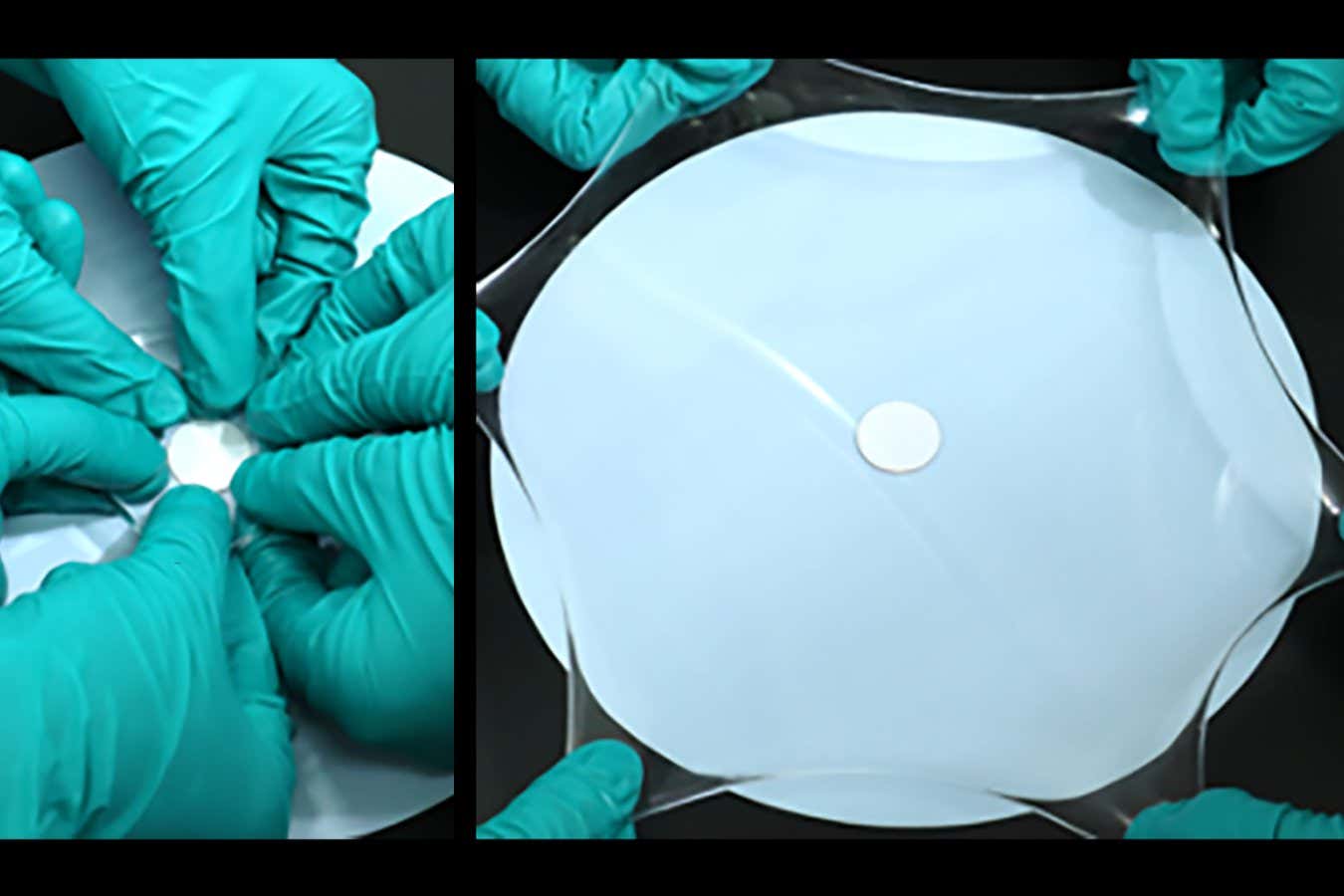

Science & Environment4 weeks agoHyperelastic gel is one of the stretchiest materials known to science

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoWould-be reality TV contestants ‘not looking real’

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoHow to unsnarl a tangle of threads, according to physics

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoMaxwell’s demon charges quantum batteries inside of a quantum computer

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks ago‘Running of the bulls’ festival crowds move like charged particles

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoIs sharing your smartphone PIN part of a healthy relationship?

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

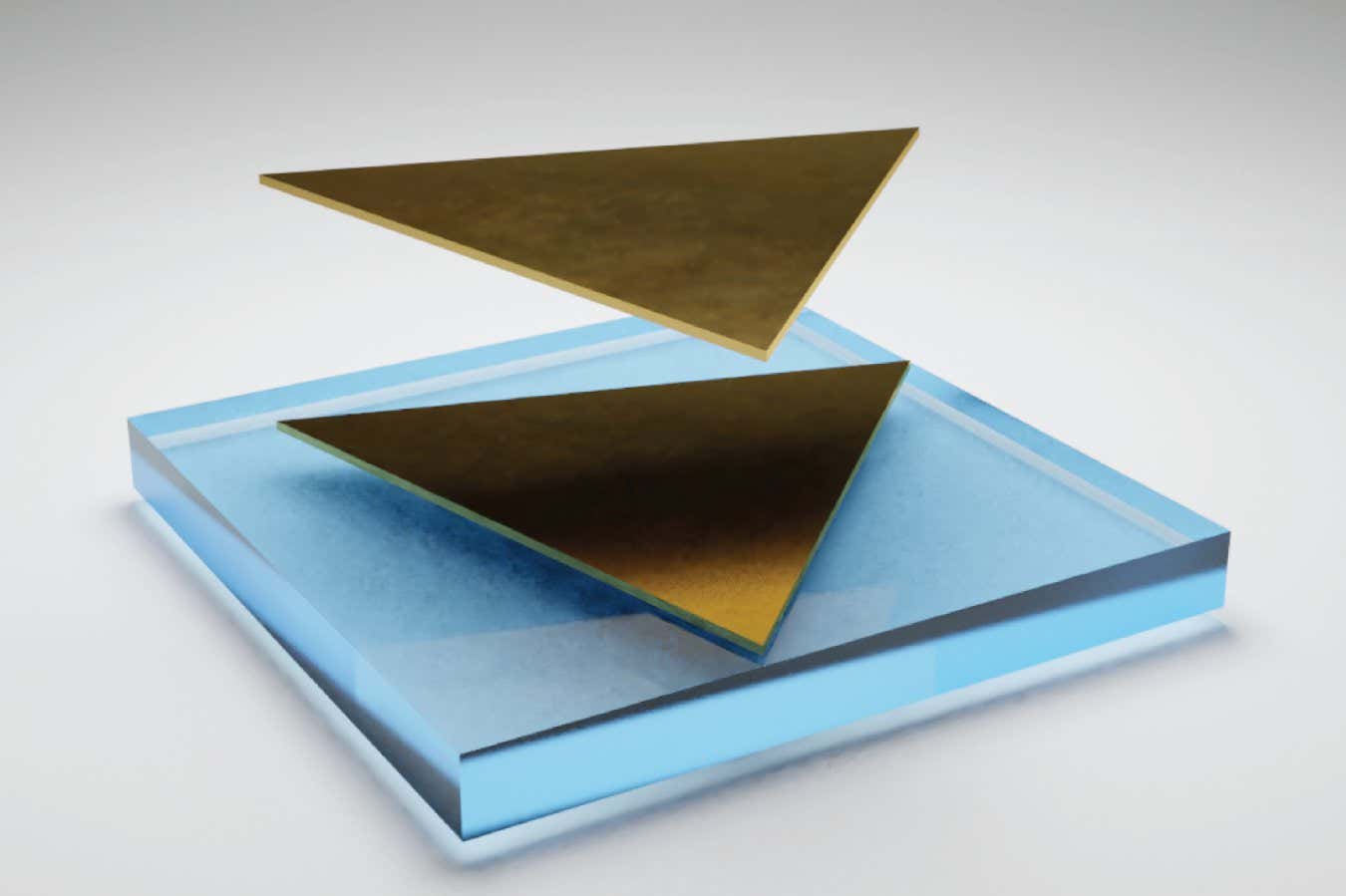

Science & Environment4 weeks agoLiquid crystals could improve quantum communication devices

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

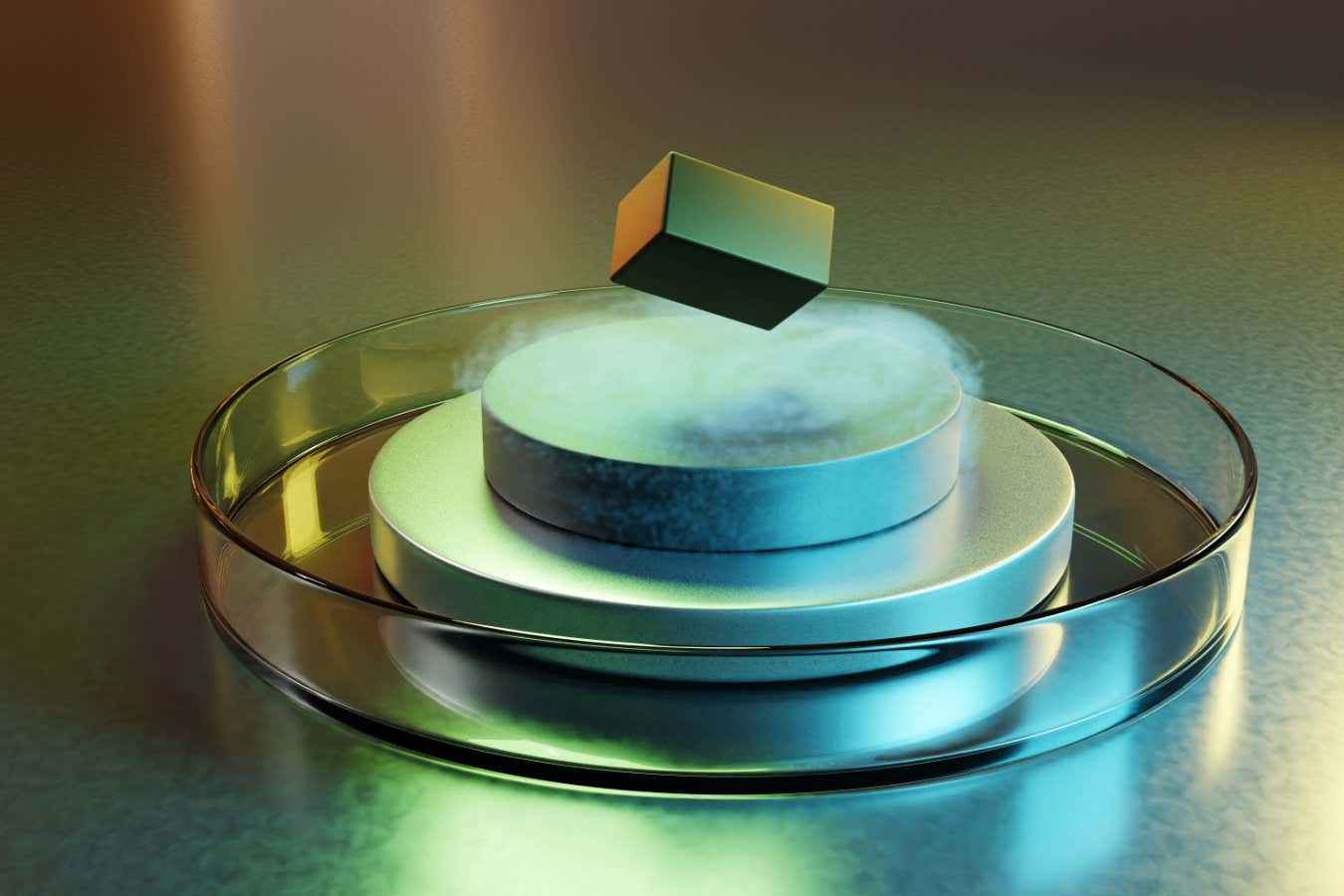

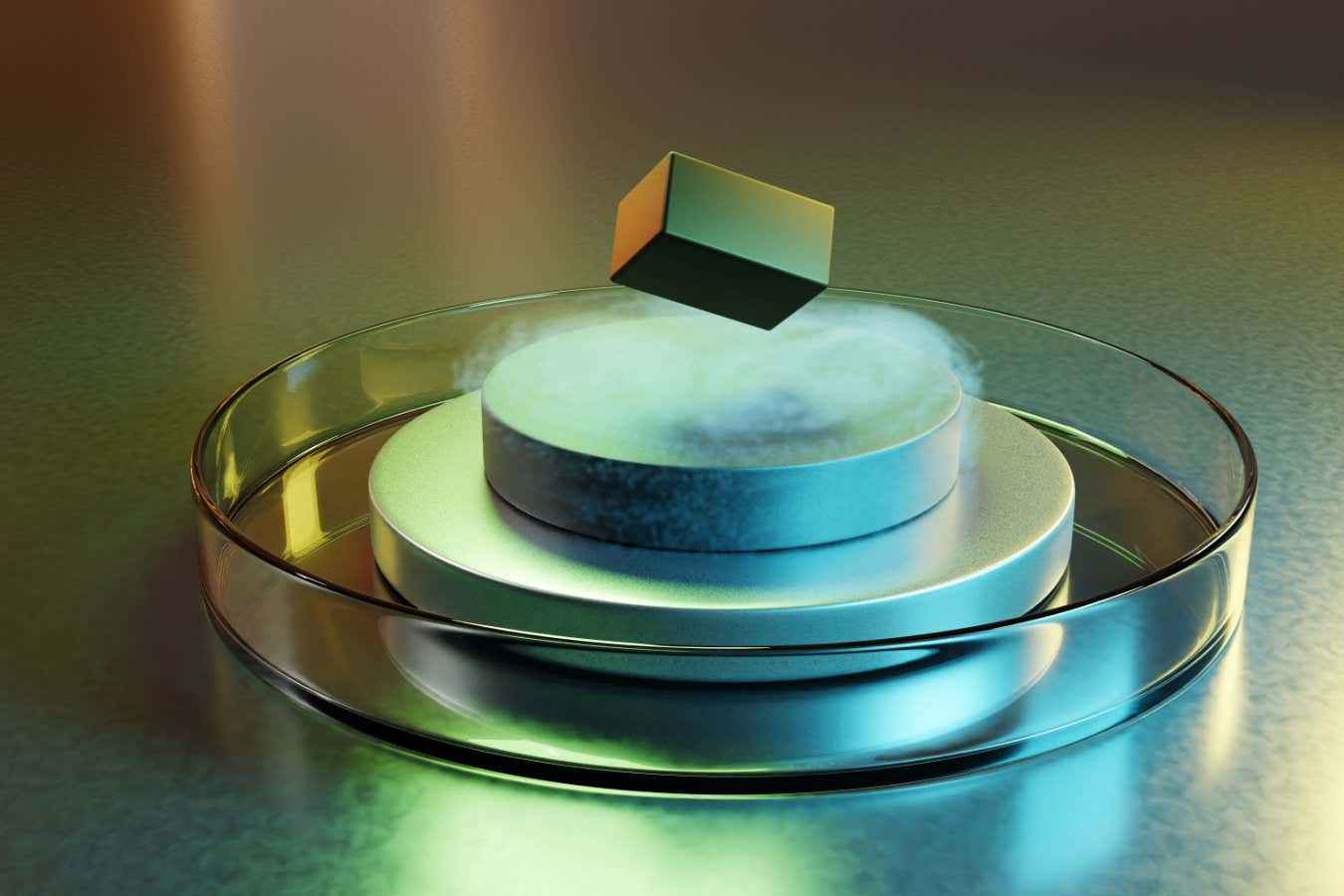

Science & Environment4 weeks agoQuantum ‘supersolid’ matter stirred using magnets

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago3 Day Full Body Women’s Dumbbell Only Workout

-

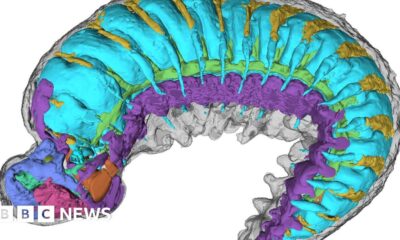

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoX-rays reveal half-billion-year-old insect ancestor

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

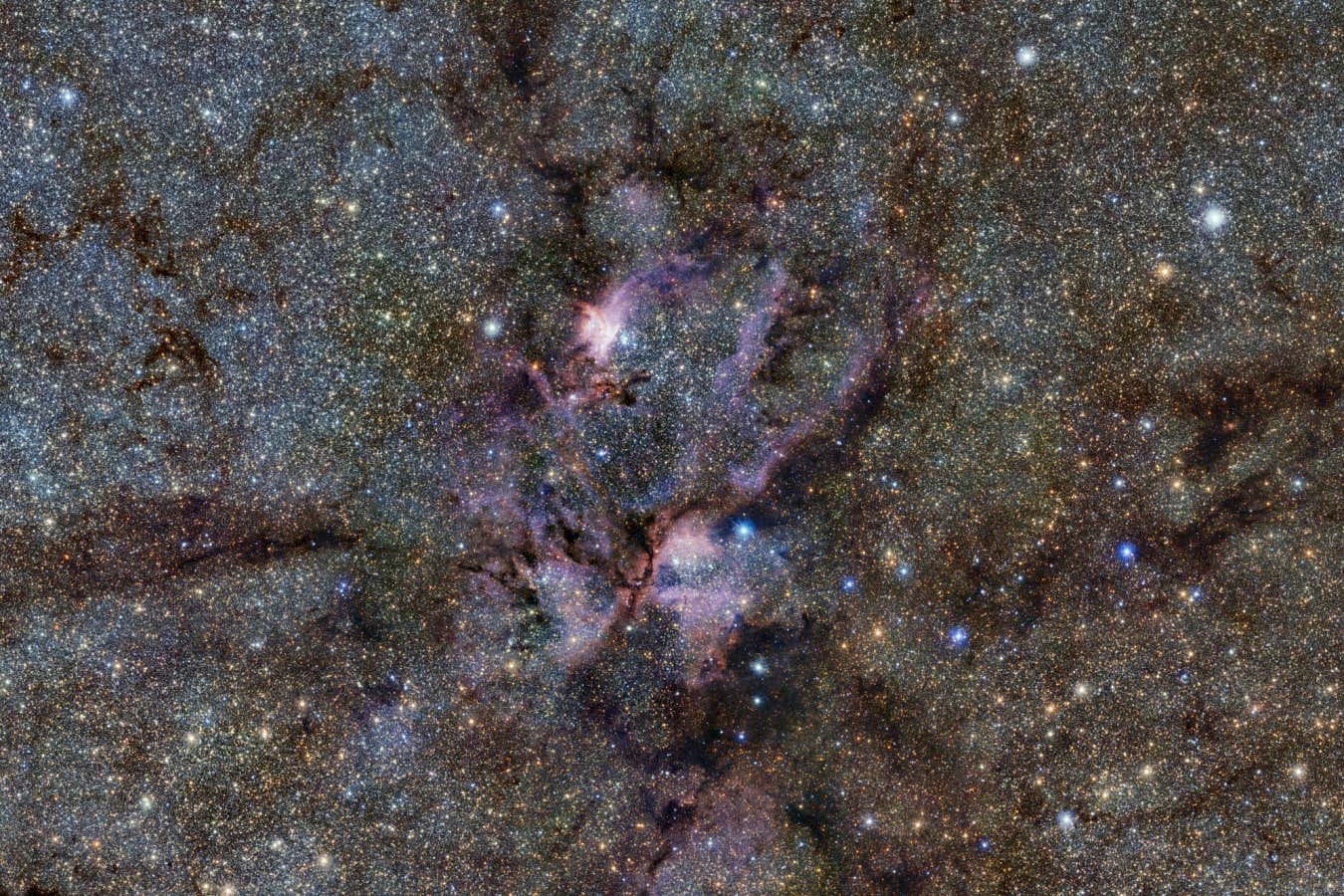

Science & Environment4 weeks agoWhy this is a golden age for life to thrive across the universe

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoSunlight-trapping device can generate temperatures over 1000°C

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoQuantum forces used to automatically assemble tiny device

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

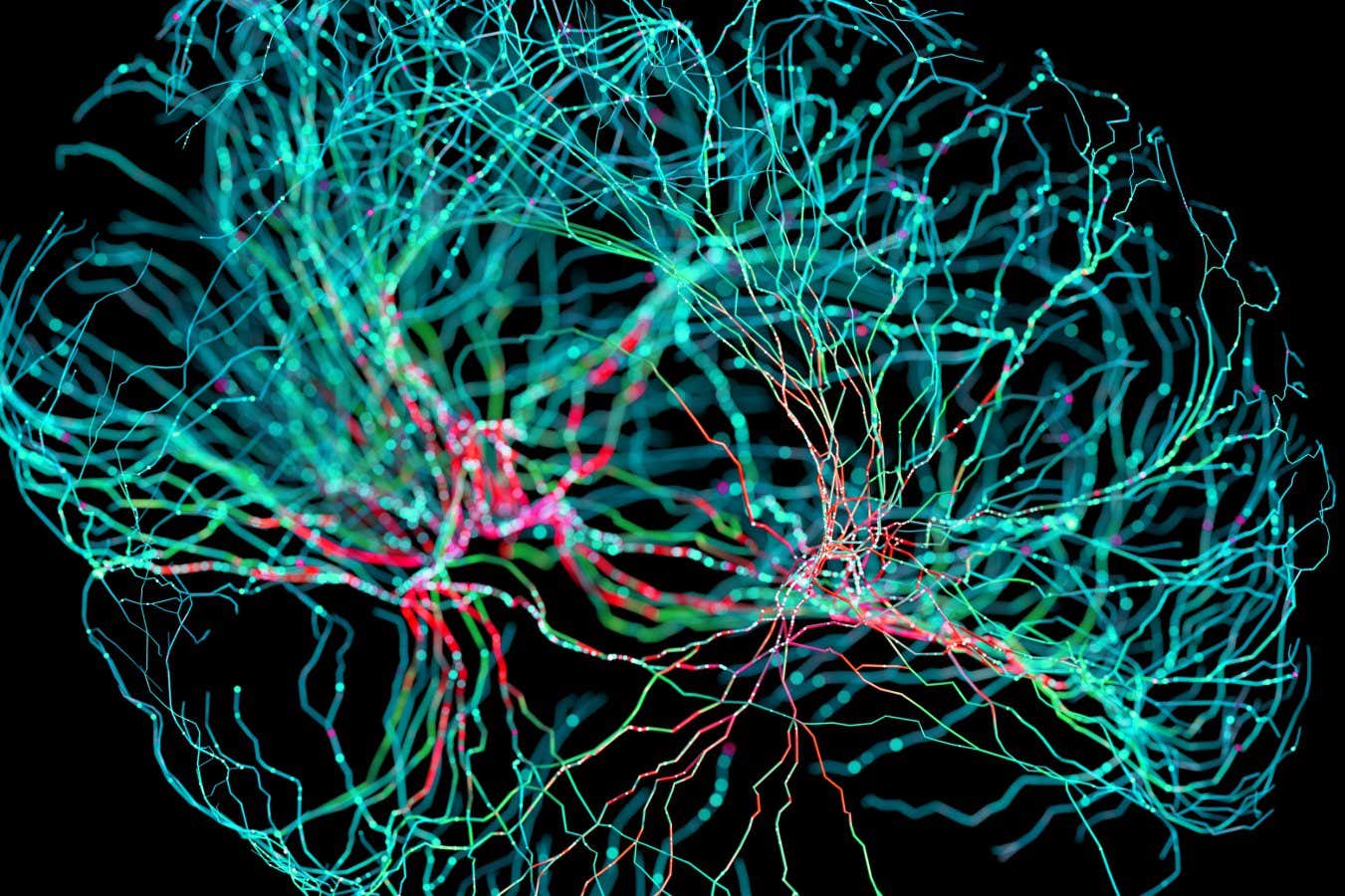

Science & Environment4 weeks agoNerve fibres in the brain could generate quantum entanglement

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

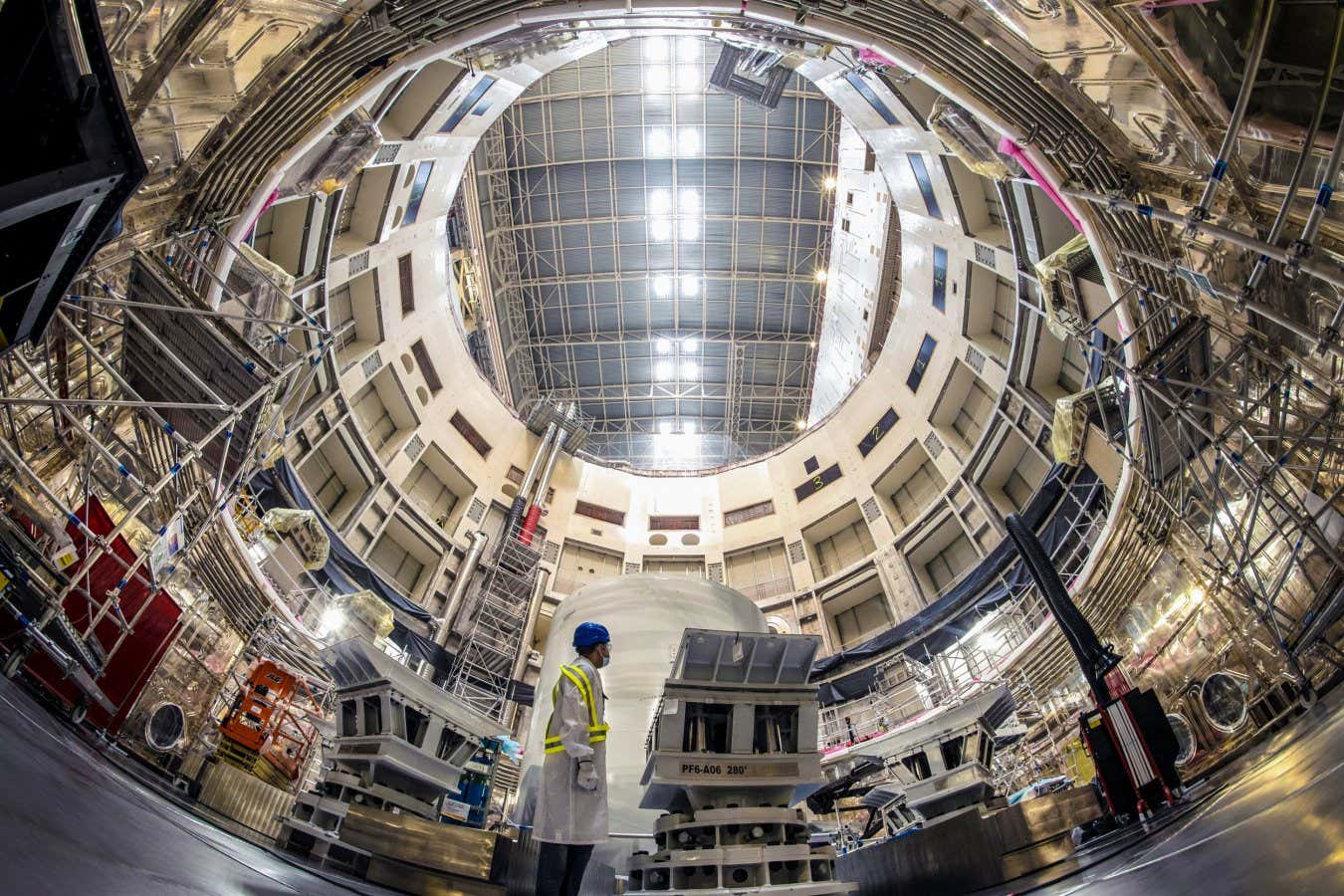

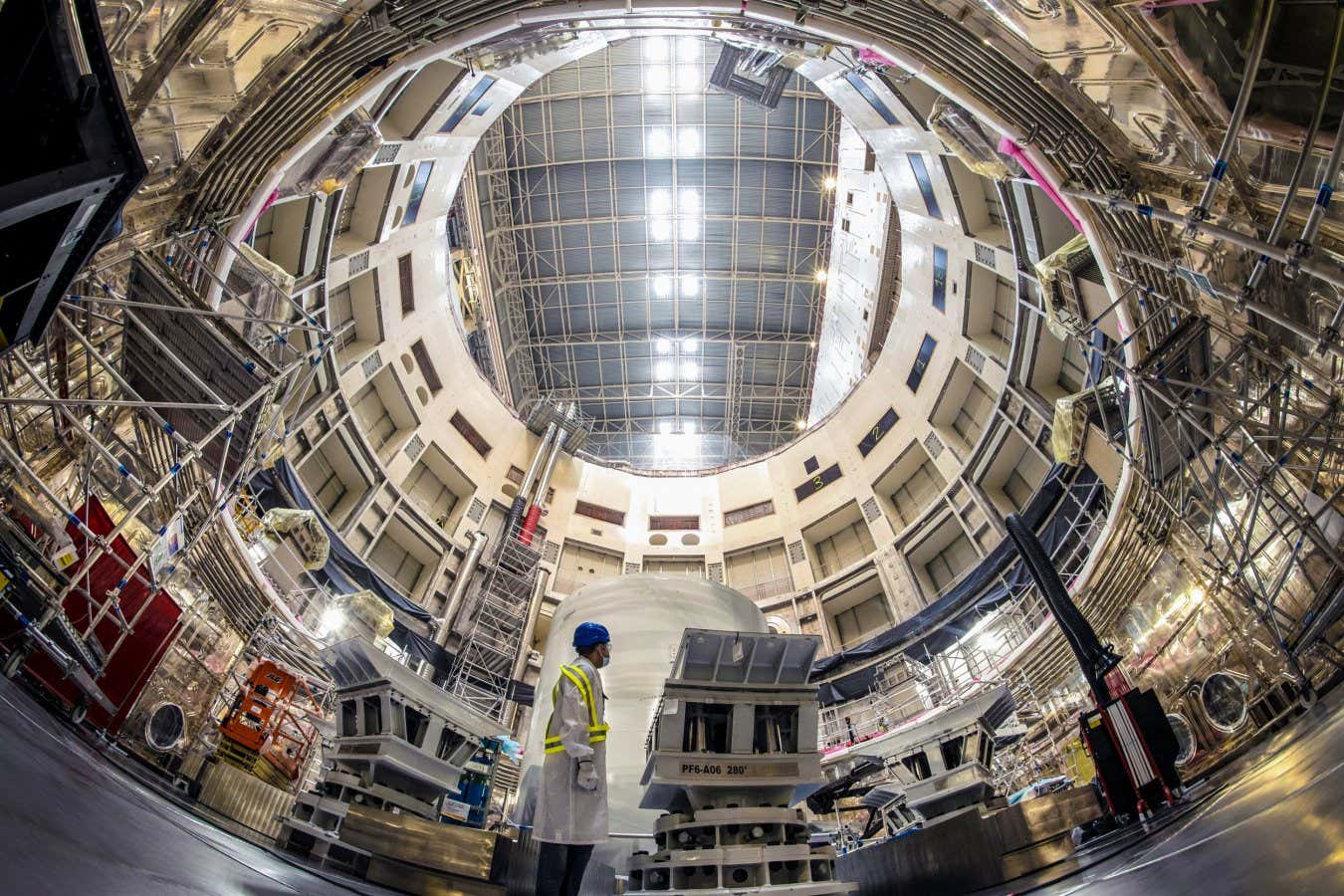

Science & Environment4 weeks agoITER: Is the world’s biggest fusion experiment dead after new delay to 2035?

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoHow to wrap your mind around the real multiverse

-

News1 month ago

the pick of new debut fiction

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoA slight curve helps rocks make the biggest splash

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoOur millionaire neighbour blocks us from using public footpath & screams at us in street.. it’s like living in a WARZONE – WordupNews

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

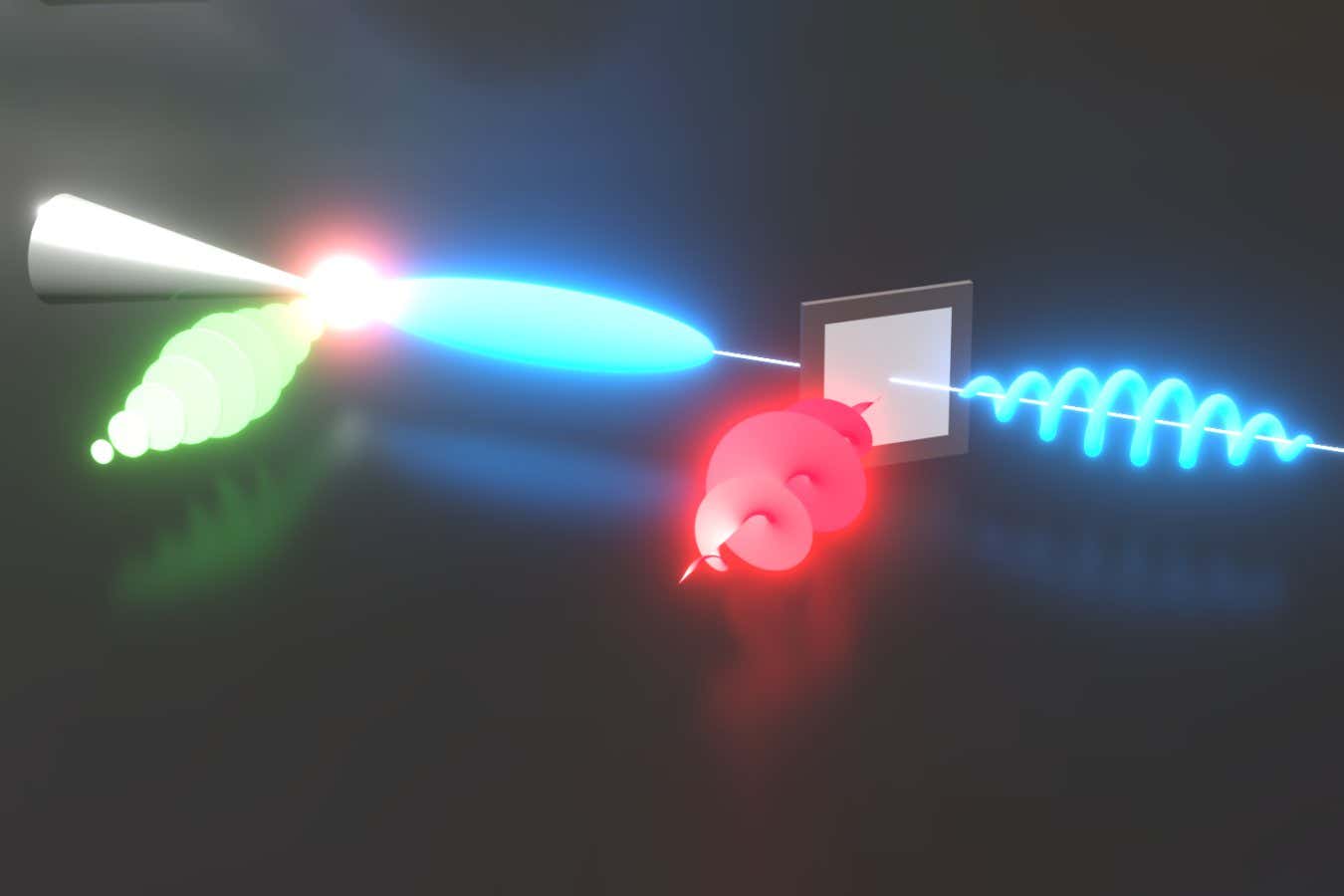

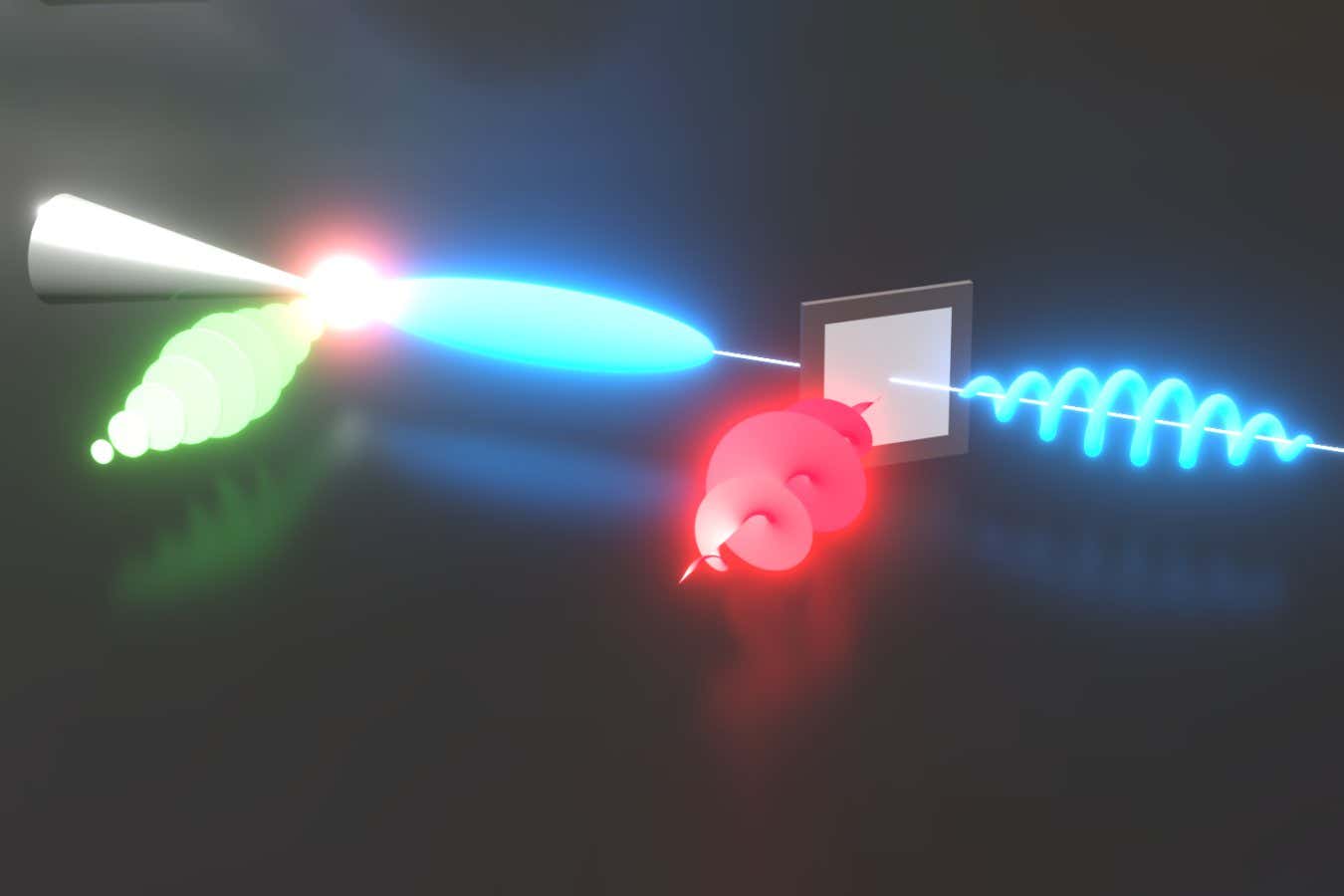

Science & Environment4 weeks agoLaser helps turn an electron into a coil of mass and charge

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoTime travel sci-fi novel is a rip-roaringly good thought experiment

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoNuclear fusion experiment overcomes two key operating hurdles

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoPhysicists are grappling with their own reproducibility crisis

-

News1 month ago

News1 month ago▶️ Hamas in the West Bank: Rising Support and Deadly Attacks You Might Not Know About

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks ago▶️ Media Bias: How They Spin Attack on Hezbollah and Ignore the Reality

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoYou’re a Hypocrite, And So Am I

-

Business3 weeks ago

Eurosceptic Andrej Babiš eyes return to power in Czech Republic

-

Sport4 weeks ago

Sport4 weeks agoJoshua vs Dubois: Chris Eubank Jr says ‘AJ’ could beat Tyson Fury and any other heavyweight in the world

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

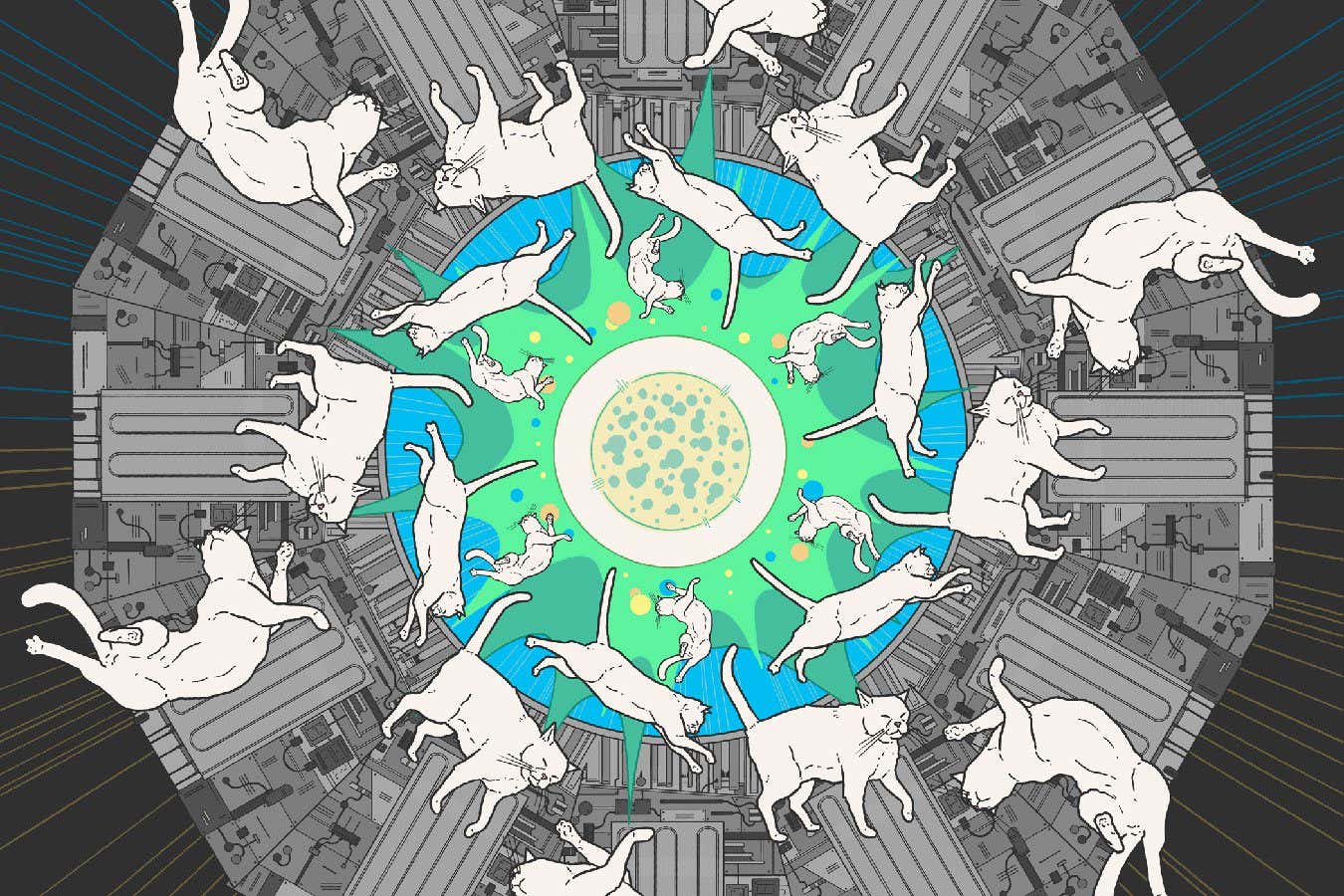

Science & Environment4 weeks agoA new kind of experiment at the Large Hadron Collider could unravel quantum reality

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoCaroline Ellison aims to duck prison sentence for role in FTX collapse

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoNew investigation ordered into ‘doorstep murder’ of Alistair Wilson

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoRethinking space and time could let us do away with dark matter

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoWhy Machines Learn: A clever primer makes sense of what makes AI possible

-

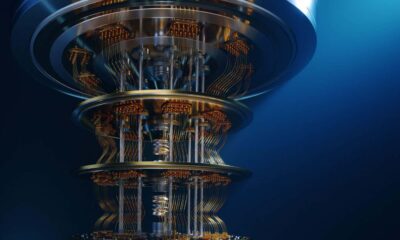

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoQuantum computers may work better when they ignore causality

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoWatch UFC star deliver ‘one of the most brutal knockouts ever’ that left opponent laid spark out on the canvas

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoA tale of two mysteries: ghostly neutrinos and the proton decay puzzle

-

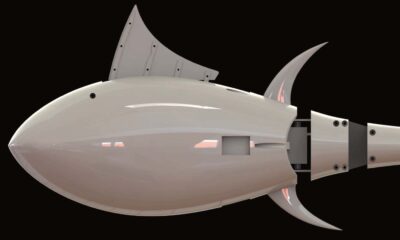

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoRobo-tuna reveals how foldable fins help the speedy fish manoeuvre

-

Business3 weeks ago

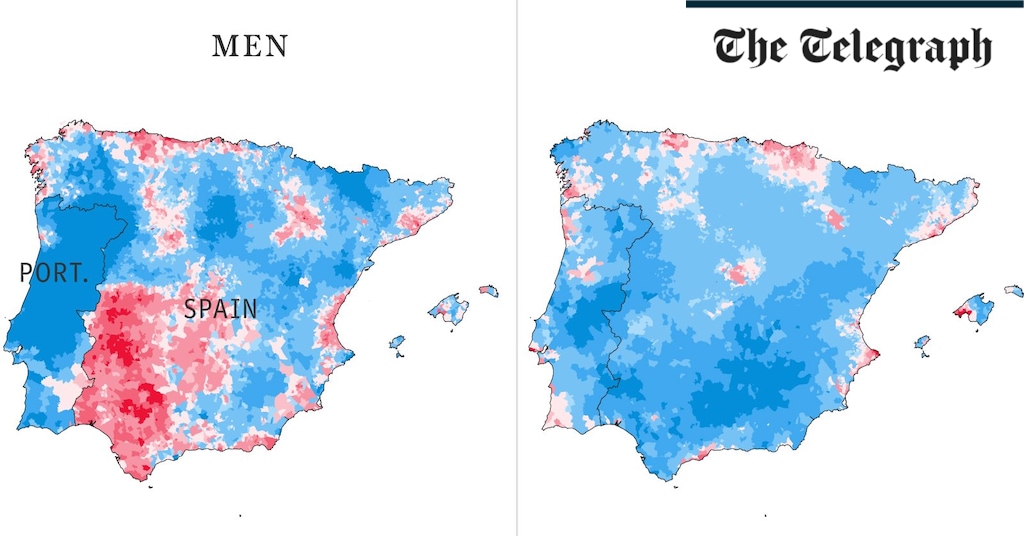

Should London’s tax exiles head for Spain, Italy . . . or Wales?

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoConor McGregor challenges ‘woeful’ Belal Muhammad, tells Ilia Topuria it’s ‘on sight’

-

Football3 weeks ago

Football3 weeks agoFootball Focus: Martin Keown on Liverpool’s Alisson Becker

-

Health & fitness4 weeks ago

Health & fitness4 weeks agoThe secret to a six pack – and how to keep your washboard abs in 2022

-

News4 weeks ago

The Project Censored Newsletter – May 2024

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks ago‘From a toaster to a server’: UK startup promises 5x ‘speed up without changing a line of code’ as it plans to take on Nvidia, AMD in the generative AI battlefield

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoMicrophone made of atom-thick graphene could be used in smartphones

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoWhen to tip and when not to tip

-

Sport2 weeks ago

Sport2 weeks agoWales fall to second loss of WXV against Italy

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoIsrael strikes Lebanese targets as Hizbollah chief warns of ‘red lines’ crossed

-

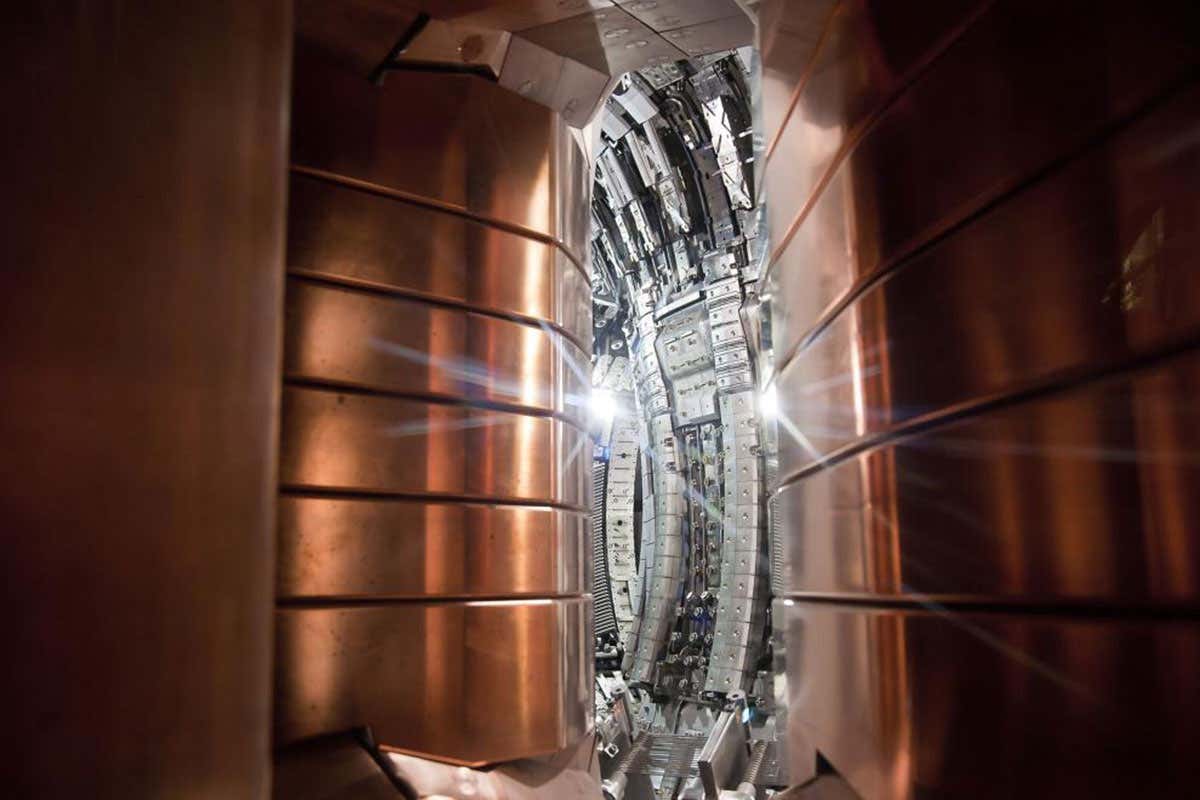

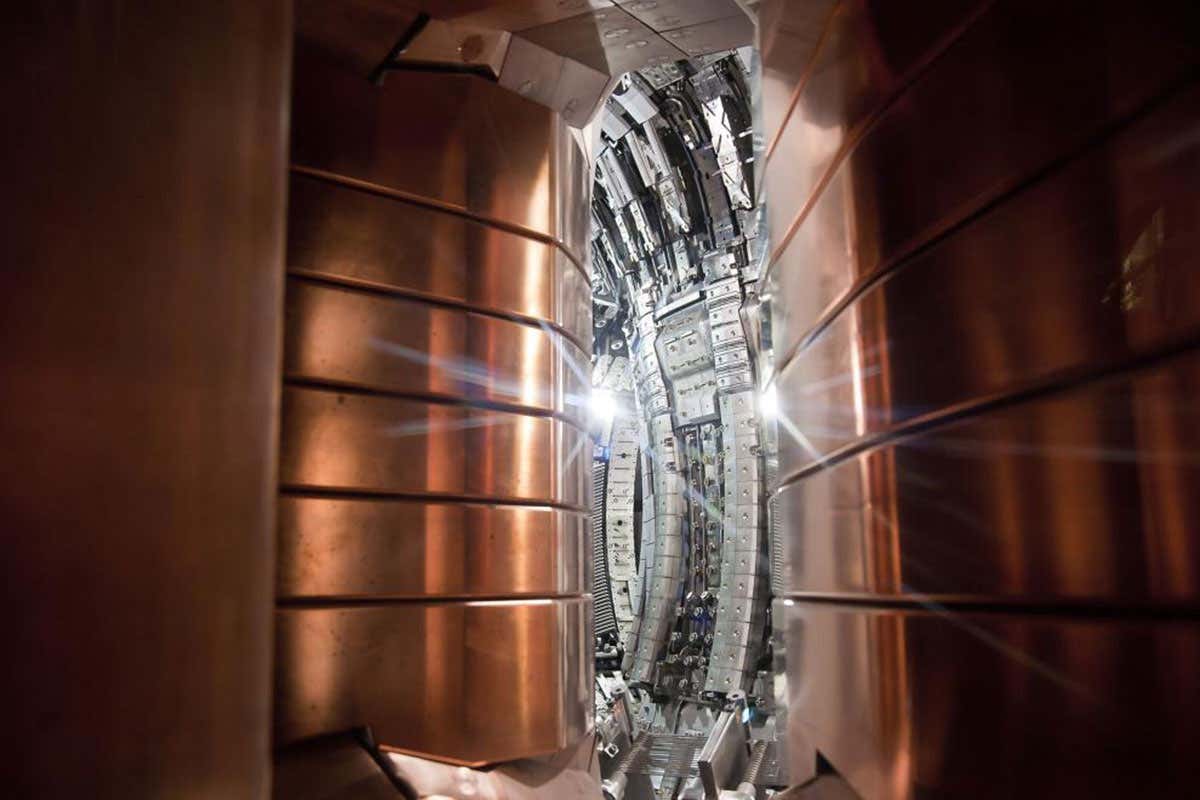

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoFuture of fusion: How the UK’s JET reactor paved the way for ITER

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoUniversity examiners fail to spot ChatGPT answers in real-world test

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoPhysicists have worked out how to melt any material

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoThe ‘superfood’ taking over fields in northern India

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoUK spurns European invitation to join ITER nuclear fusion project

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoCardano founder to meet Argentina president Javier Milei

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoCNN TÜRK – 🔴 Canlı Yayın ᴴᴰ – Canlı TV izle

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoWhy Is Everyone Excited About These Smart Insoles?

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoGet ready for Meta Connect

-

Business2 weeks ago

Ukraine faces its darkest hour

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoThis AI video generator can melt, crush, blow up, or turn anything into cake

-

Politics3 weeks ago

Robert Jenrick vows to cut aid to countries that do not take back refused asylum seekers | Robert Jenrick

-

Business2 weeks ago

DoJ accuses Donald Trump of ‘private criminal effort’ to overturn 2020 election

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoChristopher Ciccone, artist and Madonna’s younger brother, dies at 63

-

Sport4 weeks ago

Sport4 weeks agoUFC Edmonton fight card revealed, including Brandon Moreno vs. Amir Albazi headliner

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoBeing in two places at once could make a quantum battery charge faster

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoHow FedEx CEO Raj Subramaniam Is Adapting to a Post-Pandemic Economy

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoWhy we need to invoke philosophy to judge bizarre concepts in science

-

Business4 weeks ago

Thames Water seeks extension on debt terms to avoid renationalisation

-

Politics4 weeks ago

‘Appalling’ rows over Sue Gray must stop, senior ministers say | Sue Gray

-

Politics4 weeks ago

UK consumer confidence falls sharply amid fears of ‘painful’ budget | Economics

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoMeet the world's first female male model | 7.30

-

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago

Womens Workouts3 weeks ago3 Day Full Body Toning Workout for Women

-

Health & fitness3 weeks ago

Health & fitness3 weeks agoThe 7 lifestyle habits you can stop now for a slimmer face by next week

-

Politics4 weeks ago

Politics4 weeks agoTrump says he will meet with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi next week

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoEthereum is a 'contrarian bet' into 2025, says Bitwise exec

-

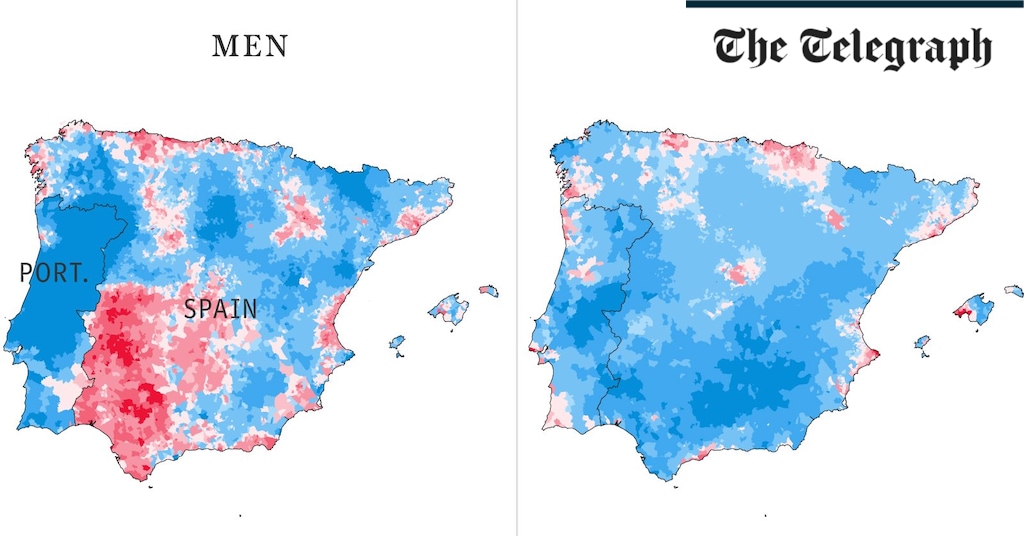

Health & fitness4 weeks ago

Health & fitness4 weeks agoThe maps that could hold the secret to curing cancer

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoDecentraland X account hacked, phishing scam targets MANA airdrop

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoBitcoin miners steamrolled after electricity thefts, exchange ‘closure’ scam: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoDZ Bank partners with Boerse Stuttgart for crypto trading

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoLow users, sex predators kill Korean metaverses, 3AC sues Terra: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoBlockdaemon mulls 2026 IPO: Report

-

MMA4 weeks ago

MMA4 weeks agoRankings Show: Is Umar Nurmagomedov a lock to become UFC champion?

-

Womens Workouts4 weeks ago

Womens Workouts4 weeks agoBest Exercises if You Want to Build a Great Physique

-

Womens Workouts4 weeks ago

Womens Workouts4 weeks agoEverything a Beginner Needs to Know About Squatting

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoFour dead & 18 injured in horror mass shooting with victims ‘caught in crossfire’ as cops hunt multiple gunmen

-

Servers computers3 weeks ago

Servers computers3 weeks agoWhat are the benefits of Blade servers compared to rack servers?

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoUkraine is using AI to manage the removal of Russian landmines

-

Business2 weeks ago

LVMH strikes sponsorship deal with Formula 1

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoHeartbreaking end to search as body of influencer, 27, found after yacht party shipwreck on ‘Devil’s Throat’ coastline

-

MMA2 weeks ago

MMA2 weeks agoPereira vs. Rountree prediction: Champ chases legend status

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoChurch same-sex split affecting bishop appointments

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoiPhone 15 Pro Max Camera Review: Depth and Reach

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoBrian Tyree Henry on voicing young Megatron, his love for villain roles

-

Business4 weeks ago

JPMorgan in talks to take over Apple credit card from Goldman Sachs

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoQuantum time travel: The experiment to ‘send a particle into the past’

-

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoTiny magnet could help measure gravity on the quantum scale

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoDorsey’s ‘marketplace of algorithms’ could fix social media… so why hasn’t it?

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoBitcoin bulls target $64K BTC price hurdle as US stocks eye new record

-

News4 weeks ago

News4 weeks agoBrian Tyree Henry on voicing young Megatron, his love for villain roles

-

CryptoCurrency4 weeks ago

CryptoCurrency4 weeks agoCoinbase’s cbBTC surges to third-largest wrapped BTC token in just one week

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoCNN TÜRK – 🔴 Canlı Yayın ᴴᴰ – Canlı TV izle

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoShocking ‘kidnap’ sees man, 87, bundled into car, blindfolded & thrown onto dark road as two arrested

You must be logged in to post a comment Login