Business

India-US trade deal: Trade team heading to Washington next week for legal pact

Earlier this month, India and the US released a joint statement to announce that a framework for an interim trade agreement has been finalised. “The joint statement lays down the contours of the deal. Now, the contours of the deal have to be translated into a legal agreement, which will be signed between the two sides,” Agrawal said.

The two sides are engaged in finalising that legal agreement, and virtual talks are going on.

“Next week, chief negotiator Darpan Jain will be leading a delegation to the US to finalise the legal (pact) to work towards the legal agreement. That work will carry on next week in Washington and, if need be, thereafter in March and July,” Agrawal said.

There is an effort to close and sign the deal in March, he said “but I have not put a deadline on it because legal agreement finalisation also has certain intricacies, which both sides will have to resolve.”

While Washington has already eliminated the 25% punitive tariffs on India for buying Russian crude, it is yet to issue an executive order to implement the reduction in reciprocal tariffs on Indian goods to 18% from 25%. “I am told they are processing it. It should be done fast. Our expectation is that it should be done this week, but in case it is not done, the team is there next week, and we can pursue and see why it is taking time,” Agrawal said. He explained that the agreement is that 18%will be done in the interim pact, and the remaining tariff lines, wherever reciprocal tariffs are expected to go down to zero, that would be done after the legal agreement is signed.

“And from our side also, any reduction in tariff, any market access, preferential market access will be extended only after the legal agreement is signed,” he said.

On India getting concessional duty access for garments made using American yarn and cotton under its bilateral trade agreement with the US, like the benefit currently extended to Bangladesh under a US trade deal, the secretary said that India imports around $200-250 million of US cotton on average. “And the variety being imported, I presume, is the same variety which we get the preferential market access,” he added.

An official said that India is a net importer of cotton and it needs more of it as it eyes higher exports of textiles to the EU and US.

Agri, digital trade

Trade agreements with the US and the EU have opened up an opportunity of $400 billion for India’s agriculture sector, an official said.

At present, India’s agricultural exports to the US are 2.8 billion, while imports are $1.5 billion. Overall, India’s imports of agri goods are worth $35 billion, while exports are valued at $51-52 billion, and the figures are increasing.

On the US including references to agriculture and digital trade in their fact sheet, which are not there in the joint statement, the official said: “Pulses weren’t there in the joint statement. So, in the factsheet it was innocuous.” Officials said that the two sides haven’t discussed digital taxes, ecommerce moratorium or equalisation levy in the negotiations in the first tranche of the trade deal.

“On barriers to digital trade, it is for both sides to identify in the BTA. Digital taxes we haven’t even discussed,” said an official.

India’s non-marine agricultural exports to the US are worth $2.8 billion and imports $1.5 billion.

On India buying DDGS (Dried Distillers Grain with Solubles) from the US, the official said: “We haven’t agreed to any GM. Anything coming into the country has to go through bio security. There are TRQ (Tariff Rate Quota) wherever we’ve opened up in agriculture”, adding that the EU and the US are $400 bn agriculture economies.

Business

Dollar Tree opens nearly half of new stores in affluent areas

Max Levchin, CEO of Affirm, provides insights into consumer spending habits based on Affirms data on ‘The Claman Countdown.’

Discount retailer Dollar Tree is opening new stores in increasingly affluent areas as it seeks to attract higher-income customers who spend more at the store per trip, a new report finds.

An analysis by Bloomberg News found that 49% of new Dollar Tree stores opened in the last six years were located in wealthier parts of metro areas around the country, up from just 41% in the preceding six years.

The share of new stores in ZIP codes with significantly higher incomes compared to the broader metro area rose to 19% in the last six years, up from 16% in the prior six years. At the other end of the spectrum, the share opened in ZIP codes with significantly lower incomes declined to 14% from 20% in the comparable periods, Bloomberg found.

Dollar stores have historically seen an uptick in business during economic downturns as more consumers look to economize, but with higher-income households driving much of consumer spending, the shift comes as a way of attracting those shoppers more frequently.

WHY SHOPPERS MAKING SIX FIGURES ARE GIVING DOLLAR TREE A BOOST

Dollar Tree is opening a rising share of new stores in more affluent areas. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Dollar Tree says that in the last quarter, 60% of new Dollar Tree customers made at least six figures. About 30% were middle-income households earning between $60,000 and $100,000, while the rest were lower-income households earning under $60,000.

While these higher-income customers visit Dollar Tree less than their lower-income peers, the company said that they spend an extra $1 on average per visit and if they were to make one additional visit per year, it would boost annual sales by $1 billion.

INFLATION EASED SLIGHTLY IN JANUARY BUT REMAINED WELL ABOVE THE FED’S TARGET

| Ticker | Security | Last | Change | Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLTR | DOLLAR TREE INC. | 126.06 | -2.37 | -1.85% |

Dollar Tree CEO Michael Creedon said late last year that the retailer serves “an increasingly broad spectrum of shoppers, from core value-focused households to middle- and higher-income shoppers who are making deliberate choices about how and where they spend.”

He added that the data “demonstrates that Dollar Tree isn’t just for tough times or for those with limited resources.”

DOLLAR GENERAL SEES INCREASE IN HIGHER-INCOME SHOPPERS LOOKING TO STRETCH THEIR DOLLARS

Dollar Tree is looking to attract more higher-income customers. (Scott Olson/Getty Images)

“While the average per household spend for our higher income customers is currently lower, even given their higher income, larger average basket size and ability to spend more, this is a simple function of trip frequency,” Creedon said.

He added that “because many of our higher income customers are still early in their relationship with Dollar Tree, their purchase frequency has significant room to grow.”

Consumers’ shopping preferences have also contributed to the pivot, as more households trade down to offset higher expenses due to inflation.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

The elevated cost of essentials like groceries and household items has forced even more of them to trade down to stores known for their heavy discounting or everyday low-price models, such as Dollar Tree, Dollar General, Walmart and Aldi.

Business

Tax filing scams seek personal info for identity theft, BBB warns taxpayers

J.P. Morgan Asset Management chief global strategist David Kelly dissects what is hard to get out of the market and more on ‘Making Money.’

Tax filing season is underway and scammers are looking to take advantage of unsuspecting taxpayers through a variety of ever-evolving scams seeking money and personal information.

The International Association of Better Business Bureaus warns that tax scams typically originate with a phone call and tend to fall into two categories.

In one, the supposed IRS agent tells the would-be victim that they owe back taxes and attempts to pressure them into paying with a prepaid debit card or wire transfer, threatening an arrest and fines for noncompliance.

The other popular tax scam tactic involves the scammer claiming they’re issuing tax refunds and asking for personal information to send the would-be victim their refund. That information may later be used for identity theft, and in the case of college students, they may be targeted with a claim that their “federal student tax” hasn’t been paid.

TAX FILING SEASON IS OFFICIALLY HERE: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW

The Better Business Bureau warns taxpayers to be cautious with when contacted by someone claiming to be from the IRS. (iStock)

The BBB report notes that tax scammers may engage in a number of tactics to try to appear legitimate. They may give a fake badge number or name, and the caller ID may indicate that the call is coming from Washington, D.C., or use a serious “robocall” recording that sounds official.

Scammers may also send a follow-up email that uses IRS logos and colors along with language that makes the email appear legitimate.

When con artists attempt to target victims, they may try to push the would-be victim into taking action immediately before they have a chance to ask questions or otherwise process the information the scammer is throwing at them.

HERE’S WHEN TAXPAYERS WILL GET THEIR REFUNDS

The IRS doesn’t initiate contact with taxpayers by phone or email, and won’t demand immediate action as taxpayers may appeal its decisions. (Kayla Bartkowski/Getty Images)

They may also demand payment through methods like wire transfers, prepaid debit cards, or other non-traditional methods because those are harder to reverse or trace. The real IRS will never demand immediate payment, require a specific form of payment, or ask for a credit or debit card number of the phone.

The BBB notes that the IRS will allow taxpayers to ask questions or appeal any amount of back taxes they owe.

Additionally, the IRS always initiates contact by mail – not by phone calls, texts, emails or social media – so taxpayers aware of that can be better prepared to parry a scammer’s attempts via phone or email. After the IRS sends a mailed letter to a taxpayer with outstanding debts, they may reach out by phone.

DATA BREACH EXPOSES PERSONAL DATA OF 25M AMERICANS

Tax scammers may use a variety of methods to target taxpayers. (iStock)

The IRS has also warned taxpayers about a mailing scam that attempts to trick victims into thinking they have a tax refund.

Taxpayers receive a cardboard envelope with a fake letter that purports to be from the IRS regarding an unclaimed refund, which requests the taxpayer provide personal and financial information.

BBB recommends that taxpayers in doubt about whether phone calls or other outreach are legitimately from the IRS should contact the agency directly to tell them about the claims and request, which should allow them to confirm whether it was actually the IRS reaching out.

GET FOX BUSINESS ON THE GO BY CLICKING HERE

It also suggests filing taxes as early as possible to avoid the threat of identity theft, as a scammer could attempt to use your information to file a fake return.

Business

Gen Z, Locked Out of Home Buying, Puts Its Money in the Market

A generation of young people locked out of homeownership has found another way to build wealth: putting money into the stock market.

The share of people 25 to 39 years old making annual transfers to investment accounts more than tripled between 2013 and 2023 to 14.4%, outpacing increases for those 40 and over, according to data from the JPMorgan Chase Institute. The share of 26-year-olds who transferred funds to investment accounts since turning 22 shot up from 8% in 2015 to 40% as of May 2025. The numbers don’t include people investing in 401(k)s.

“We’ve seen really strong, surprisingly strong growth in retail investing in recent years among people who may otherwise be first-time home buyers,” said George Eckerd, the research director for wealth and markets at the institute.

The age range includes young millennials and there is overlap in the numbers between investors and homeowners, but Eckerd was struck by the rise in young and lower-income investors at the same time that home buying activity has fallen. That, he said, has tilted the balance of wealth accumulation toward financial markets for young people.

Copyright ©2026 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8

Business

Wynnstay Group Plc (WYNSF) Q4 2025 Earnings Call Transcript

Operator

Good morning, and welcome to the Wynnstay Group plc Full Year Results Investor Presentation. [Operator Instructions] Before we begin, I would like to submit the following poll. And I would now like to hand you over to CEO, Alk Brand. Good morning to you, sir.

Alk Brand

CEO & Executive Director

Good morning, everybody. It is a pleasure to talk to all of you. My name is Alk Brand. I’m the CEO of Wynnstay Plc. And today with me is Rob Thomas, my colleague, our CFO, and we’re delighted to talk to you about the results of our previous financial year. We would like to focus on quite a few things in the presentation. So I will focus on some of the highlights of the year, Rob as well, followed by a discussion of our business model, update on some of our changes. Rob will focus on our results and the business review, and then I will come back in on our summary and outlook.

So I’m happy to say that the past financial year was a successful one and was the first year of our Project Genesis. We are now in year 2 of a 3-year project to improve the financial results of the business. And I’m pleased that after year 1, looking back, we can say that it’s been a very successful year.

So with that, I’m going to hand over to my colleague, Rob, and I’m looking forward to discussing this with our investors today. Thank you for joining us.

Rob Thomas

CFO & Executive Director

Thank you, Alk, and good morning, everyone. As Alk mentioned, we are pleased with

Business

GOP senators urge permanent divestment of Lukoil assets

Fox News senior national correspondent Rich Edson interviews U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent about potential new sanctions on Russia.

FIRST ON FOX – A group of Republican senators is urging Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to ensure that any sale of Russian energy giant Lukoil’s foreign assets results in permanent divestment from Moscow, warning against what they describe as potential “shell game” proposals that could return control to Russia.

In a letter Monday, Sens. Tim Sheehy, R-Mont., Steve Daines, R-Mont., and John Barrasso, R-Wyo., voiced support for President Donald Trump’s sanctions strategy targeting Russia’s energy sector, but raised concerns that some proposed deals may undermine the administration’s foreign policy goals.

The senators said certain proposals under consideration could amount to temporary “caretaker or custodial arrangements” designed to revert ownership back to Lukoil if U.S. sanctions are lifted or tensions between Washington and Moscow ease.

They also warned that other potential transactions could involve a “buy-and-flip” approach that might place strategic oil and gas assets into the hands of U.S. adversaries, including China, potentially jeopardizing American national security and global energy stability.

INSIDE THE SEA WAR TO CONTAIN ‘DARK FLEET’ VESSELS — AND WHAT THE US SEIZURE SIGNALS TO RUSSIA

Steve Daines, John Barrasso, and Tim Sheehy are urging Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to ensure that any sale of Russian energy giant Lukoil’s foreign assets results in permanent divestment from Moscow. (Pete Marovich-Pool/Getty Images; Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images; Michael Ciaglo/Getty Images / Getty Images)

The letter follows the Treasury Department’s October 2025 sanctions on Lukoil and the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s requirement that the company divest its non-Russian holdings to non-blocked entities.

It also comes amid ongoing divestment talks, including Lukoil’s Jan. 29 announcement of a conditional, non-exclusive agreement to sell its subsidiary Lukoil International GmbH, which holds its international assets, to the Carlyle Group, a U.S. investment firm.

The transaction would not include assets in Kazakhstan, according to the company.

LINDSEY GRAHAM SAYS TRUMP BACKS RUSSIA SANCTIONS BILL

Tanker trucks are seen near the PJSC Lukoil Oil Company tank storage in Neder-Over-Heembeek on Nov. 15, 2025, in Brussels, Belgium. (Thierry Monasse / Getty Images)

Lukoil International GmbH maintains operations and minority interests in oil and gas fields in Iraq, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Egypt and the Republic of the Congo, among other countries.

It also has stakes in several pipelines and owns refineries and thousands of retail stations across nearly 20 European countries.

‘THEY WERE SPYING’: SULLIVAN SOUNDS ALARM ON JOINT RUSSIA-CHINA MOVES IN US ARCTIC ZONE

A worker oversees the loading of oil supplies into freight wagons at the Lukoil-Nizhegorodnefteorgsintez oil refinery in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, on Dec. 4, 2014. (Andrey Rudakov/Bloomberg via Getty Images / Getty Images)

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD THE FOX NEWS APP

The senators described the portfolio as strategically significant to global energy markets and warned that any sale must ensure the assets remain permanently outside Russian control.

“We cannot allow U.S. adversaries to regain control over these valuable assets that have funded so much of Russia’s aggression and must prioritize bids from firms that seek to invest in and build these assets to further American national interests,” Sheehy, Daines and Barrasso wrote.

Business

Sealed Air declares quarterly cash dividend of $0.20 per share

Sealed Air declares quarterly cash dividend of $0.20 per share

Business

Mexico stocks lower at close of trade; S&P/BMV IPC down 0.13%

Mexico stocks lower at close of trade; S&P/BMV IPC down 0.13%

Business

Cabinet Acknowledges Visa Measures to Boost Thailand’s Tourism and Economy

The Cabinet approved visa measures to boost tourism and Thailand’s economy, including special exemptions, a Destination Thailand Visa, and plans for e-Visas, with emphasis on security and eligibility revisions.

Key Points

- Cabinet Acknowledgment and Short-Term Measures:

- The Cabinet endorsed visa measures from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to boost tourism and the economy as of May 28, 2024.

- Short-term actions include a visa exemption for 93 countries, allowing 60-day stays, and an initial Visa on Arrival (VOA) list of 31 nations.

- Medium and Long-Term Strategies:

- Medium-term plans involve reducing non-immigrant visa categories from 17 to 7 by August 31, 2025, and expanding the e-Visa system to all Thai embassies by January 1, 2025.

- Long-term initiatives include a digital pre-travel authorization system with the Thailand Digital Arrival Card (TDAC) introduced from May 1, 2025.

- Ongoing Assessments and Security Considerations:

- Ongoing measures also involve expanding VOA eligibility to eight more countries and updating retirement visa criteria.

- The Ministry raised concerns regarding national security related to misuse of visa exemptions, and a re-appointed visa policy committee will review these measures promptly.

The Cabinet has acknowledged visa measures and guidelines proposed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to promote tourism and stimulate Thailand’s economy, in line with the Cabinet resolution of May 28, 2024.

The measures are organized into short-, medium-, and long-term frameworks. The Department of Consular Affairs has summarized progress as follows.

Implemented short-term measures include designating 93 countries and territories eligible for a special visa exemption, allowing stays of up to 60 days for tourism, short-term work, or business. Thailand has also approved an initial list of 31 countries and territories eligible for Visa on Arrival (VOA).

Thailand has also introduced the Destination Thailand Visa (DTV) to attract high-quality visitors, digital nomads, and participants in cultural activities such as Muay Thai, traditional Thai massage, Thai cooking, and other soft-power initiatives.

The Cabinet approved the ED Plus non-immigrant visa for foreigners entering Thailand for study or for study combined with work.

A visa policy committee has been reappointed, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs will hold additional meetings.

Medium-term measures include reducing the number of non-immigrant visa codes from 17 to 7, effective August 31, 2025, and expanding the e-Visa system to all 94 Thai embassies and consulates worldwide, effective January 1, 2025.

Long-term measures focus on developing online pre-travel authorization systems. Immigration authorities introduced the Thailand Digital Arrival Card (TDAC), which has been in use since May 1, 2025.

Ongoing measures include a second-phase expansion of VOA eligibility to 8 additional countries and revised long-stay visa criteria for elderly foreigners seeking retirement in Thailand.

The Ministry noted observations regarding potential impacts on national security and Thailand’s image, as some foreign nationals have misused visa exemptions for unauthorized work or illegal activities. The newly appointed visa policy committee will review these measures at the earliest opportunity.

Source : Cabinet Acknowledges Visa Measures to Boost Thailand’s Tourism and Economy

Other People are Reading

Business

Banca Generali S.p.A. (BGNMF) Q4 2025 Earnings Call Transcript

Operator

Good afternoon. This is the Chorus Call Conference operator. Welcome, and thank you for joining the Banca Generali Full Year 2025 Results Conference Call. [Operator Instructions]

At this time, I would like to turn the conference over to Mr. Gian Maria Mossa, CEO and General Manager of Banca Generali. Please go ahead, sir.

Gian Mossa

GM, CEO & Executive Director

So good afternoon, and thank you for attending our full year results conference call. Before we get into our results, I want to quickly comment the market reaction to the recent announcement of a U.S. initiative called the Altruist. That is basically a tool, an artificial intelligence tool for the automated tax planning that in Italy is largely relevant just because for any investment related taxation, the tax situation is handled directly by the withholding agents. So basically the banks or the financial intermediary and not by the client.

So the volatility on our stock today comes from this U.S.-centric situation. That simply doesn’t fit with the Italian wealth management context and even less with Banca Generali also because we are not a brokerage platform. So as you know, and we said it several times, Italy has a unique economic and social environment where the wealth is still mostly invested in liquid assets, think of real estate kind of companies, not listed equity. And it remains very much sort of, say, family affair.

So in this context, our clients look for discretion, human guidance and not automatic

Business

Cuba’s Havana piles with trash as US chokehold halts garbage trucks

Cuba’s Havana piles with trash as US chokehold halts garbage trucks

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

Crypto World7 days ago

Crypto World7 days agoU.S. BTC ETFs register back-to-back inflows for first time in a month

-

Video6 hours ago

Video6 hours agoBitcoin: We’re Entering The Most Dangerous Phase

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoLuxman Enters Its Second Century with the D-100 SACD Player and L-100 Integrated Amplifier

-

Video3 days ago

Video3 days agoThe Final Warning: XRP Is Entering The Chaos Zone

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Crypto World6 days agoBlockchain.com wins UK registration nearly four years after abandoning FCA process

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Crypto World3 days ago

Crypto World3 days agoBhutan’s Bitcoin sales enter third straight week with $6.7M BTC offload

-

Video5 days ago

Video5 days agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

Crypto World7 days ago

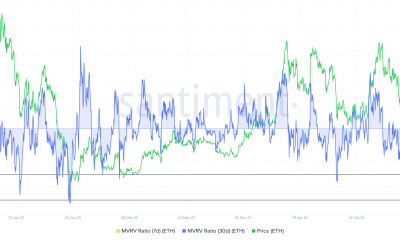

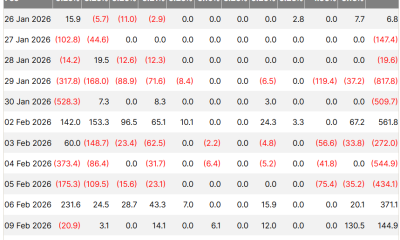

Crypto World7 days agoEthereum Enters Capitulation Zone as MVRV Turns Negative: Bottom Near?

-

NewsBeat1 day ago

NewsBeat1 day agoThe strange Cambridgeshire cemetery that forbade church rectors from entering

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoBarbeques Galore Enters Voluntary Administration

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Crypto World6 days agoCrypto Speculation Era Ending As Institutions Enter Market

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoEthereum Price Struggles Below $2,000 Despite Entering Buy Zone

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoWhy was a dog-humping paedo treated like a saint?

-

NewsBeat1 day ago

NewsBeat1 day agoMan dies after entering floodwater during police pursuit

-

Crypto World3 days ago

Crypto World3 days agoBlackRock Enters DeFi Via UniSwap, Bitcoin Stages Modest Recovery

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoUK construction company enters administration, records show

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoWinter Olympics 2026: Australian snowboarder Cam Bolton breaks neck in Winter Olympics training crash