Crypto World

Axelar Network Integrates Stellar to Power Institutional Cross-Chain Finance

TLDR:

-

- Axelar Network has integrated Stellar, connecting its payments infrastructure with cross-chain interoperability tools

- Solv Protocol, Stronghold, and Squid Router launched live on the Axelar-Stellar integration at launch day.

- Stronghold bridges SHx between Stellar and Ethereum, maintaining a unified 1:1 token supply across both chains.

- Axelar’s 2026 roadmap targets compliant, institutional-grade infrastructure, aligning closely with Stellar’s focus.

Axelar Network has completed its integration with Stellar, linking two key infrastructure layers in the digital asset space.

The move connects Stellar’s payments and asset issuance capabilities with Axelar’s cross-chain interoperability protocol. At launch, Solv Protocol, Stronghold, and Squid Router are already live and operational.

The integration opens new pathways for tokenization, trading, and yield products across blockchain networks for institutional and retail participants alike.

New Cross-Chain Capabilities Reach Builders Immediately

Axelar Network confirmed the integration is live, with projects already building on the combined infrastructure. Stellar brings high throughput, low fees, and native compliance tooling to the table.

Its ecosystem includes payment providers, fintech platforms, and capital markets participants with an established developer base.

The Axelar team announced the milestone on X, stating: “Stellar is now live on Axelar. This integration expands institutional-grade onchain finance, connecting @StellarOrg’s strengths in payments and asset issuance with Axelar’s interoperability layer. At launch, @SolvProtocol, @strongholdpay, and @squidrouter are already live.”

Solv Protocol is among the first to build on the combined stack. Solv is a major allocator in tokenized real-world assets and holds the largest onchain Bitcoin reserve.

Through Axelar and Stellar, Solv can extend yield-bearing products into cross-chain markets. Builders can bridge solvBTC to Stellar today using Solv’s cross-chain application.

Stronghold is bridging its SHx token between Stellar and Ethereum through Axelar’s protocol. The bridge maintains a 1:1 supply across both networks while supporting consistent liquidity.

As noted in the announcement, the bridge allows “SHx holders to move assets freely between the two networks while maintaining a unified 1:1 supply.” SHx holders can already move assets between the two chains via Squid Router.

Institutional Adoption Drives the Integration’s Strategic Direction

Axelar Network’s 2026 roadmap, outlined by Common Prefix, centers on institutional adoption and compliant infrastructure.

Stellar’s focus on payments, regulated asset issuance, and compliance-oriented tools aligns well with that direction.

The roadmap specifically targets “strengthening economic security, enabling compliant and privacy-aware infrastructure, and building institutional products up the stack.”

Squid Router already supports bridging assets including XLM and solvBTC on the integrated network. Its role as a liquidity routing layer allows Stellar-based assets to access broader markets without fragmenting developer workflows. This gives builders immediate cross-chain reach from the Stellar ecosystem.

Financial institutions across global markets continue to explore onchain infrastructure for settlement and trading. Axelar and Stellar co-authored a joint article on onchain retail payments published in The Stablecoin Standard.

That collaboration reflects a shared focus on production-ready infrastructure built for institutional participants.

Axelar Network’s integration with Stellar is fully available to builders today. The announcement confirmed that “applications can begin connecting onchain assets and services across both networks today.”

The integration positions both ecosystems to support the continued growth of regulated, cross-chain digital asset products.

Crypto World

Relative Strength Index (RSI): Trading Strategies, Settings, and Market Applications

RSI is a popular momentum indicator in technical trading across forex, stock, and cryptocurrency* markets. The Relative Strength Index (RSI) is a momentum oscillator developed by J. Welles Wilder that measures the speed of price movements on a 0–100 scale. Traders use it to detect overbought/oversold conditions, trend strength, pullbacks, and exhaustion.

Although often viewed as a basic oscillator, the RSI plays a more nuanced role in professional trading strategies, particularly when combined with trend and volatility indicators. Understanding how the RSI behaves in different market environments may help traders refine entries, implement risk management strategies, and confirm trade setups.

In this article, we will consider how the RSI indicator works, how it is calculated, and how it can be applied in practical trading strategies across multiple asset classes.

Takeaways

- The Relative Strength Index (RSI) is a momentum indicator that measures the speed and magnitude of recent price movements to evaluate whether an asset is overbought or oversold.

- Developed by J. Welles Wilder, the RSI is plotted on a scale from 0 to 100 and is most commonly calculated over a 14-period timeframe.

- At its core, the RSI compares the average size of recent gains with the average size of recent losses over a defined period.

- Traditionally, RSI trading rules suggest that readings above 70 indicate overbought conditions, while readings below 30 signal oversold levels.

- Besides overbought and oversold signals, the indicator can provide divergence, trend strength, and failure swings signals.

What Is the Relative Strength Index?

The Relative Strength Index (RSI) is a momentum oscillator in modern technical analysis. Developed by J. Welles Wilder Jr. and introduced in 1978 in New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems, the indicator measures the speed and magnitude of recent price movements in order to evaluate underlying market momentum.

The RSI is plotted on a scale from 0 to 100 and is classified as an oscillator because it fluctuates within a fixed range rather than following price directly. This structure allows traders to evaluate whether buying or selling pressure is strengthening or weakening relative to recent market activity.

In practice the RSI functions less as a reversal indicator and more as a momentum persistence gauge. In directional markets the oscillator spends extended time in one half of its range, reflecting order-flow imbalance rather than exhaustion. Professional traders therefore interpret extreme readings as trend participation signals unless market structure begins to break.

Although the RSI is often introduced as a simple overbought-oversold tool, its practical application in professional trading is considerably broader. In leveraged markets such as forex and CFDs, traders use the indicator to identify pullbacks within trends, detect momentum divergence, and refine entry timing across multiple timeframes. The RSI therefore functions less as a standalone signal generator and more as a contextual momentum filter within broader trading systems.

The RSI belongs to the family of bounded momentum oscillators introduced by J. Welles Wilder in New Concepts in Technical Trading Systems (1978), alongside the average true range (ATR), the average directional movement index (ADX), and the parabolic stop and reverse (Parabolic SAR).

RSI Formula and Calculation

How is RSI calculated? It’s quite difficult to calculate the RSI. Fortunately, you don’t need to do it manually, as it’s one of the standard indicators implemented in most trading platforms. For instance, you can use TickTrader to examine the RSI without making complicated calculations.

However, it’s worth understanding how the indicator is measured to know which metrics can affect its performance.

The RSI Formula Explained

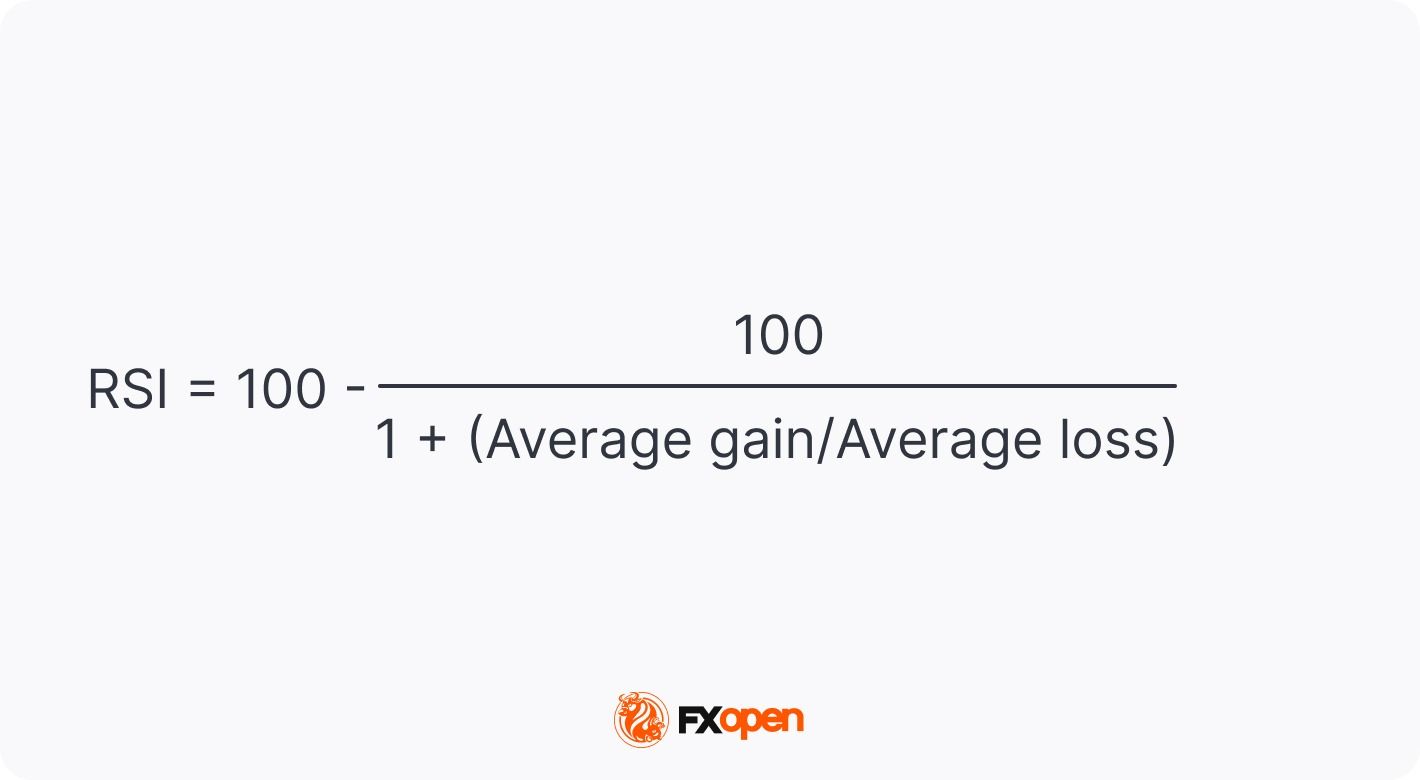

RSI formula

The calculation involves three main steps. First, the average gain and average loss over the selected period are determined. Second, these values are used to calculate relative strength, defined as the ratio of average gains to average losses. Finally, this ratio is transformed into an index value between 0 and 100 using the RSI formula.

The most popular RSI period is 14, meaning its values are based on closing prices for the latest 14 periods, regardless of the timeframe. We will use this period as an example of RSI calculations.

The standard RSI formula description:

Step 1: Average Gain and Average Loss

To calculate average gains and losses, you need to calculate the price change from the previous period.

Note: If the current price is higher than the previous one, add the gain to a total gain variable. If the price declined from the previous period, add the figure to a total loss variable.

After you calculate the change for all 14 periods, you need to add up the gains and divide them by 14 and sum up the losses and divide the total by 14.

Step 2: Calculate the Relative Strength (RS)

RS = Average Gain / Average Loss

To calculate the relative strength, divide the average gain by the average loss.

Step 3: Calculate the RSI

Now that you calculated the RS, you can proceed with the RSI value. For this, you need to add 1 to RS, divide 100 by the sum, and subtract the result from 100.

Relative Strength Index = 100 – 100 / (1 + RS)

Because the calculation uses smoothed averages of gains and losses, the RSI reacts to volatility contraction faster than to volatility expansion. This asymmetry explains why the indicator often gives early signals near market tops but delayed signals near lows.

What RSI Setting Do Traders Use?

The standard period is 14. Shorter lookback periods produce a more sensitive indicator that reacts quickly to price changes but generates more noise. Longer periods smooth out fluctuations but may lag behind rapid market shifts. This trade-off explains why RSI settings are often adjusted according to strategy type, whether scalping, day trading, or swing trading.

The following adjustments are common depending on strategy and timeframe:

Scalping strategies often use shorter RSI periods to capture rapid momentum shifts on lower timeframes. While this increases signal frequency, it also requires stricter risk management due to higher noise levels.

Want to learn how to read the RSI indicator signals?

How Is the RSI Indicator Used in Trading?

How to interpret the RSI indicator? There are four common ways to use the RSI indicator when trading: spot overbought and oversold conditions, find price divergences, implement failure swings for reversal signals, and determine market trends.

Relative Strength Index: Overbought/Oversold Indicator

The traditional interpretation of RSI levels focuses on the 70 and 30 thresholds. Readings above 70 are commonly described as overbought, while readings below 30 are considered oversold. However, in professional trading environments these thresholds are treated as reference zones rather than absolute signals.

The 70/30 framework works primarily in rotational markets. During macro-driven trends, price commonly continues moving after entering overbought or oversold territory because positioning flows dominate short-term mean reversion. In these conditions the RSI defines pullback zones rather than reversal zones.

During sustained uptrends, the RSI typically fluctuates between 40 and 80 (sometimes reaching 90 in very strong trends). Pullbacks often hold above 40, showing that bullish momentum remains intact. In sustained downtrends, the RSI usually ranges between 20 and 60, with rallies failing near 60, reflecting persistent selling pressure. These shifting RSI ranges may help traders assess trend strength rather than relying solely on the traditional 70/30 overbought–oversold levels.

Sustained RSI range shifts usually reflect systematic positioning rather than retail momentum. When the oscillator establishes a higher equilibrium range, dips towards the mid-zone often coincide with passive liquidity absorption rather than trend rejection.

On the daily chart of the GBP/USD pair, the RSI entered the oversold area on 22nd April, left it for a while on 4th May, but returned to it and continued moving upwards only on 15th May.

An example of the oversold RSI

Additionally, when using overbought/oversold signals, traders keep in mind that they can reflect an upcoming correction, not a trend reversal. The GBP/USD pair was trading in a strong downtrend, and the RSI provided a signal of a short-term correction only.

To distinguish between corrections and reversals, traders combine the RSI with other tools. A cross of a moving average can confirm a change in the trend.

Oversold RSI strategy

On the chart above, the RSI broke above the 30 level on 28th September. A trader could go long, using a trailing take profit. After the MA/EMA cross occurred (1), a trader could trail the take-profit target. Another option would be to place the take-profit order at the closest resistance level (2) and wait for the cross to confirm the reversal signal. After the confirmation, a trader could open another buy position and drive the uptrend.

RSI Divergence Strategy

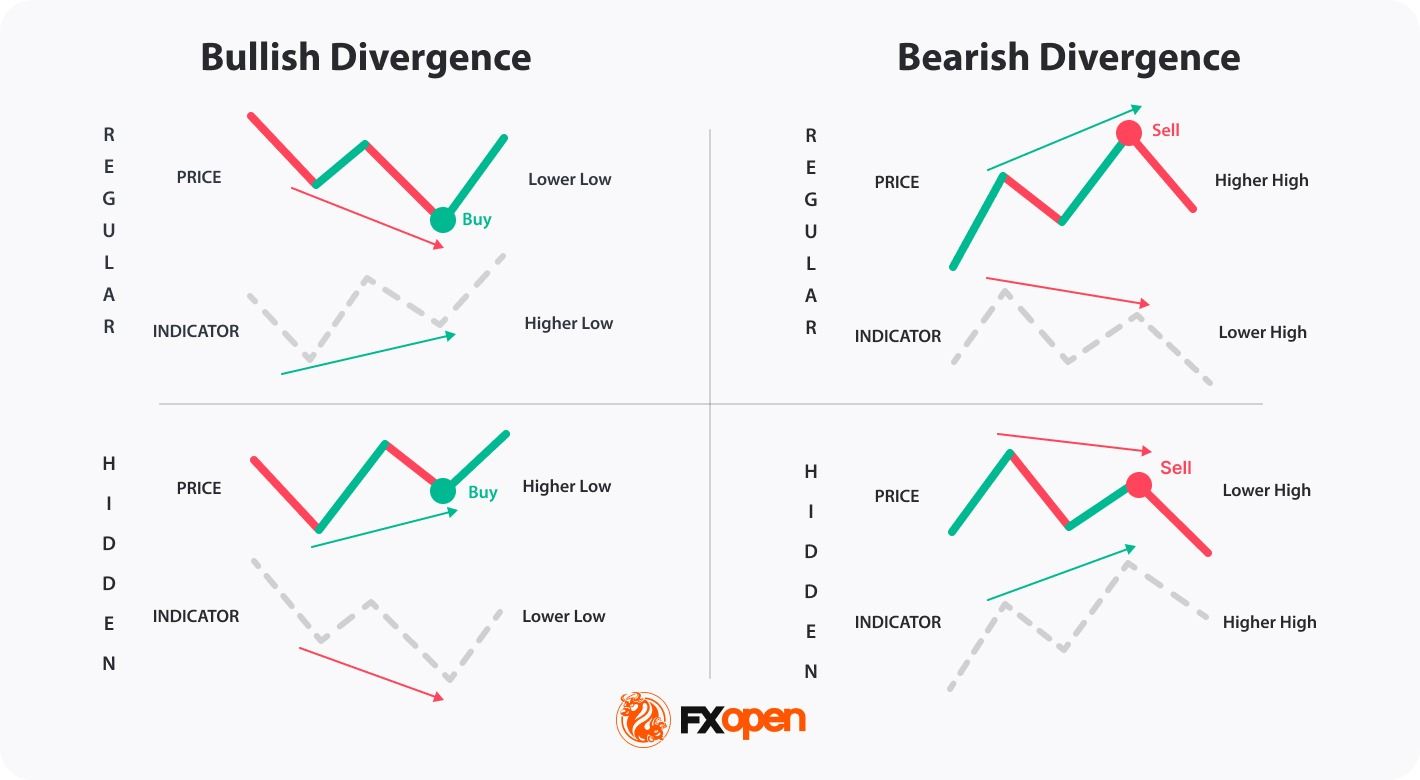

RSI is a divergence indicator. Another option for using the RSI is to look for divergences between the indicator and the price chart. Divergence occurs when price action and indicator momentum move in opposite directions, signalling a potential shift in underlying market dynamics.

A convention widely used in exchange educational materials is:

- An RSI bullish divergence forms when price records a lower low while the RSI prints a higher low. This pattern indicates that selling pressure is weakening even as price continues to decline.

- An RSI bearish divergence, by contrast, appears when price reaches a higher high but the RSI forms a lower high, suggesting diminishing upward momentum.

Divergence is more popular when it occurs near key support or resistance levels. However, because divergence can persist for extended periods before price reverses, it is rarely traded in isolation. Many traders confirm RSI divergence using tools such as the MACD or structural breaks in market structure.

Hidden divergence is another variation that signals trend continuation rather than reversal. In trending markets, this form of divergence may help traders identify pullbacks that are likely to resolve in the direction of the prevailing trend.

- A bullish divergence forms when the price rises with higher lows, but the relative strength index declines with lower lows, traders expect the price to move upwards.

- A bearish divergence forms when the price falls with lower highs, but the relative strength index moves upwards with higher highs, traders believe the price will decline.

Regular and hidden RSI divergence

Divergence frequently precedes momentum slowdown instead of immediate reversal. Markets often transition into consolidation before changing direction, which is why many traders wait for structure breaks rather than trading the first divergence signal. For example, in liquid index markets the first divergence often leads to range formation before trend change.

In the RSI example chart below, the indicator and the price formed a regular bearish divergence. As a result, the price fell (1). There was another divergence before the fall, but the price decline was short-lived (2). This highlights risks associated with the incorrect signals the RSI divergence may provide.

An example of the RSI divergence

RSI Failure Swings: A Reversal Signal

Another signal that traders can consider is failure swings of the RSI which occur before a strong trend reversal. Although it is less common than the others, traders can add it to their list of tools.

The theory suggests traders don’t consider price actions but look at the indicator alone.

- Bullish reversal. A trend may turn bullish when the RSI breaks below 30, leaves the oversold area, falls to 30 but doesn’t cross it and rebounds, continuing to rise.

- Bearish reversal. A trend may reverse down when the RSI enters the overbought area, crosses below 70, and returns to 70 but bounces and continues falling.

An example of RSI failure swings

Failure swings lose significance during volatility expansion events such as economic releases, when directional movement is driven by repricing rather than momentum decay.

In the chart above, the RSI trading indicator broke below 30, left the oversold area, and retested the 30 level (1). At the same time, the price formed the bottom, and the downtrend reversed upwards (2).

Failure swings are more common on short-term timeframes and do not always reflect a trend reversal. Therefore, traders combine the RSI with trend and volume indicators.

How Traders Identify Market Trends with RSI

The RSI can be used to identify a trend direction. Constance Brown, the author of multiple books about trading, noticed in her book Technical Analysis for the Trading Professional that the RSI indicator doesn’t fluctuate between 0 and 100. In a bullish trend, it moves in the 40-90 range. In a bearish trend, it fluctuates between 10 and 60.

To identify the trend, traders consider support and resistance levels. In an uptrend, the 40-50 zone serves as support. In a downtrend, the 50-60 range acts as resistance.

An example of trend determination using the RSI

In the chart above, the RSI stayed above 40 as the price was moving in a solid uptrend. Once it broke below the 40-50 support level (1), the trend changed (2).

However, there may be incorrect signals. In the chart below, the RSI broke below the support level twice, but the trend didn’t change.

An example of unsuccessful trend detection using RSI

Ranges may vary depending on the trend strength, price volatility, and the period of the RSI.

RSI and Simple Moving Average

Usually, the RSI indicator consists of a single line. However, there are variations of the indicator. It can be combined with the simple moving average. The moving average usually has the same period as the RSI.

The rule is that when the RSI breaks below the SMA, the price is supposed to fall (1). When the RSI rises above the SMA, the price is expected to increase (2).

RSI and Simple Moving Average

However, there are some aspects to consider. Firstly, traders avoid using RSI/SMA cross signals in the ranging market as the lines move close to each other and cross all the time, providing many fake signals. Secondly, a cross doesn’t determine the period of a rise or a fall. Traders use additional tools to identify where the price may turn around.

Note: The RSI is sensitive to volatility clustering. During news-driven sessions the indicator’s thresholds lose value because price movement is distribution-driven rather than momentum-driven.

RSI Trading Strategies Used by Professional Traders

Professional use of the RSI typically involves integrating the indicator into structured trading frameworks rather than relying on single signals. Several widely used approaches illustrate how momentum analysis can support decision-making.

What Is the 70-30 RSI Trading Strategy?

70-30 RSI Trading Strategy

The 70-30 RSI strategy simply uses the overbought and oversold RSI readings to identify potential turning points. However, instead of simply going short above 70 (overbought RSI) and long below 30 (oversold RSI), traders typically apply a few levels of refinement.

Entry:

- Traders determine if the trend is bullish or bearish.

- They apply a trend filter. The RSI can produce false signals in a strong trend, showing overbought for a long time in a bullish trend and vice versa. They often use the 70-30 strategy to look for shorts when the price rallies in a downtrend and longs when the price dips in an uptrend.

- They enter the market when the RSI crosses back into the normal range. For instance, they’ll open a short trade when the RSI falls back below 70, indicating that a potential bearish reversal may be underway.

Stop Loss:

- Stop losses are often set beyond a nearby swing point.

Take Profit:

- Profits might be taken at an area of support or resistance when the RSI hits the opposite extreme (e.g. 70 when long), or when other indicators signal a price reversal.

Mean-reversion RSI strategies statistically depend on market volatility compression. As volatility expands, breakout continuation tends to dominate over oscillator reversal signals.

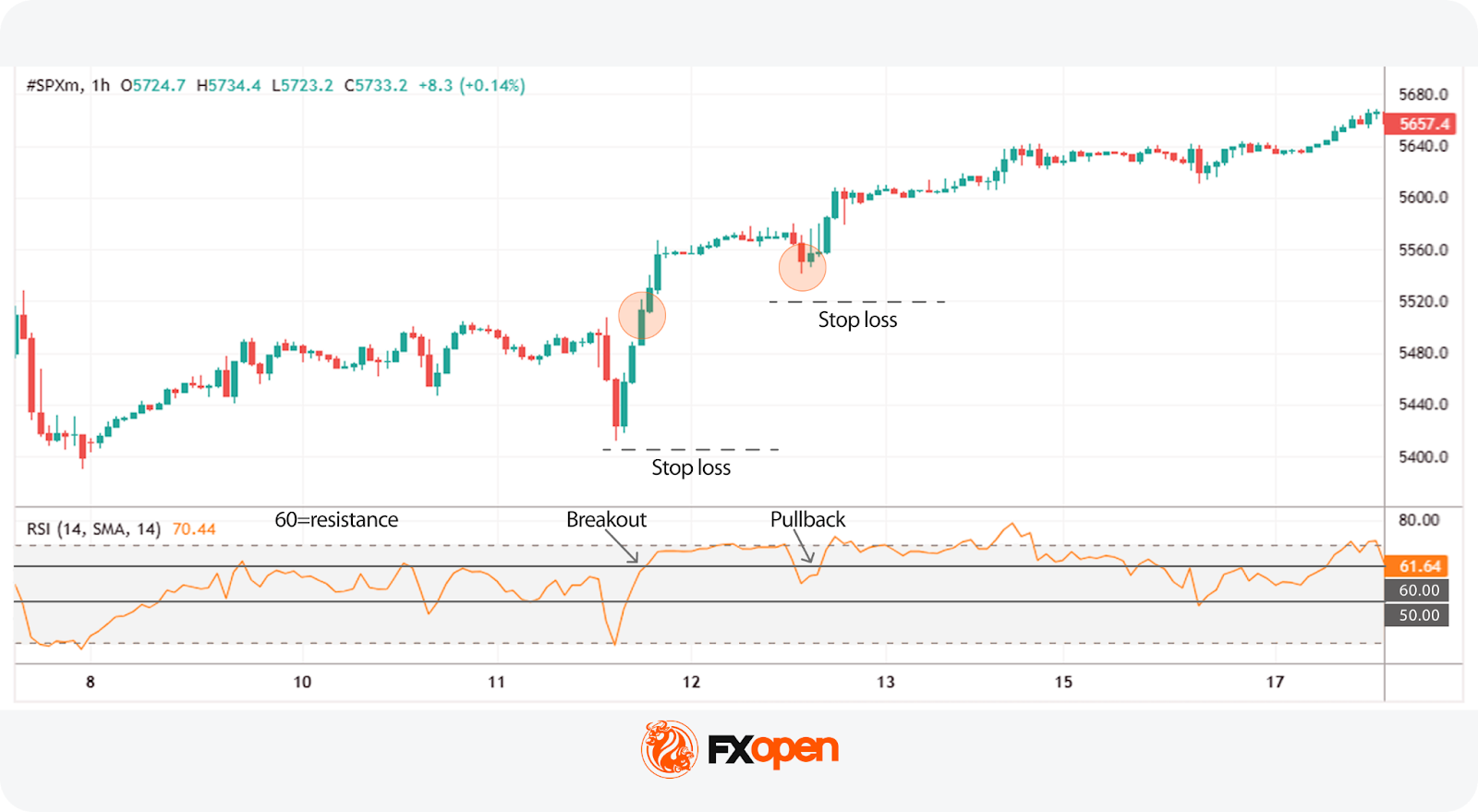

50-60 and 40-50 Trading Strategies

50-60 RSI Trading Strategy

What is the 50-60 RSI trading strategy? The 50-60 RSI strategy works on the idea that the market shows bullish momentum above 50, with 60 acting as a resistance level. When the price breaks through 60, it can signal that bullishness is strong, offering a potential entry point.

Note:

- Despite the name, the same logic can be applied in a bearish trend, where 40 acts as a support level.

- This strategy is popular in markets with a strong trend. Indices, such as the S&P 500 and Nasdaq 100, or commodities like gold, that exhibit strong trends are often chosen by traders.

Entry:

- Traders may enter the market when the price crosses above 60 for the first time.

- Alternatively, they might wait for a pullback to 60 before going long.

Stop Loss:

- A stop loss may be set beyond the nearest major swing point or just beyond the entry candle on a pullback.

- Alternatively, some traders manually stop out if the price crosses below 50.

Take Profit:

- Profits might be taken when the price crosses below 50, giving room for the trade to run in a strong trend. However, this may limit potential returns when trading on short-term timeframes. Therefore, some traders prefer the closest resistance levels.

Typical RSI Strategy Comparison

RSI Meaning in Trading: Forex, Stocks, and Crypto* Markets

The RSI is applied across asset classes, but it behaves differently because persistence characteristics vary. Equity indices exhibit autocorrelation, currencies exhibit mean reversion around macro levels, and digital assets display momentum clustering. RSI interpretation should therefore be adjusted to the instrument’s structural behaviour rather than fixed thresholds.

In forex trading, where macroeconomic factors often drive sustained directional moves, the RSI is commonly used to identify pullbacks within trends rather than outright reversals. Currency pairs can remain overbought or oversold for extended periods when central bank policy or macro data supports a strong directional bias.

What is the RSI indicator in the stock market? In the stock markets, the indicator is frequently applied to mean-reversion strategies around key support and resistance levels. Stocks tend to exhibit more frequent range-bound behaviour than major currency pairs, making traditional overbought-oversold interpretations somewhat more applicable.

Cryptocurrency* markets, characterised by high volatility and rapid sentiment shifts, often produce extreme RSI readings. In this environment, divergence analysis becomes particularly valuable, as momentum frequently weakens before price reverses.

How to Use the Relative Strength Index with Other Indicators

In professional trading systems, the RSI is rarely used in isolation. Combining momentum analysis with trend, volatility, and volume tools may help traders filter signals and false entries.

RSI with MACD

RSI and MACD (moving average convergence divergence) are oscillators. However, they measure momentum differently, which allows one to confirm the signals of another. Usually, traders look for RSI overbought/oversold signals and MACD divergence. For instance, when the RSI is in the oversold zone but the MACD has a bullish divergence with the price chart, traders consider this a confirmation of a coming price rise. Read our article RSI vs. MACD.

RSI with Moving Averages

Early signals are one of the limitations of the RSI indicator. Therefore, traders often combine them with lagging technical analysis tools. An exponential moving average (EMA) is one of the options. Traders add two EMAs with different periods to the chart and wait for a cross to confirm the trend reversal signal the RSI provided.

RSI with Bollinger Bands

Bollinger bands are used similarly to the RSI, showing when the market is possibly overbought or oversold. Used together, these two indicators can provide confluence; for example, if the RSI indicates overbought and the price has closed through the upper band, then there may be an increased likelihood of a bearish reversal, and vice versa.

RSI with On-Balance Volume (OBV)

The on-balance volume (OBV) is a tool that tracks volume to confirm trends. Paired with the RSI, it has two uses. The first is that it can indicate trend strength. If the RSI is falling alongside the OBV, the bearish trend is likely genuine and vice versa. The second is confirming divergences. The OBV can diverge from the price like the RSI, so if both diverge, a reversal may be inbound.

Using RSI on Trading Platforms

Most trading platforms include the RSI as a standard built-in indicator. Platforms such as MetaTrader 4 and MetaTrader 5 allow traders to adjust periods, apply smoothing, and set custom alert levels. Also, you can implement the RSI indicator into your trading strategy on TradingView and TickTrader platforms, which also allow you to set up the indicator for your unique trading style.

Professional traders often integrate RSI signals into multi-timeframe analysis. For instance, a higher-timeframe RSI reading may define directional bias, while a lower-timeframe signal provides entry timing. This approach reduces the likelihood of trading against broader market momentum.

Pros and Cons of the RSI Indicator

Although the relative strength index is one of the most popular indicators, it has limitations. Let’s explore the two sides of the coin.

Benefits of the RSI in Trading

The relative strength index is a useful tool because of:

- Numerous signals. The RSI provides different signals so traders with different trading approaches can add it to their tool list.

- Numerous assets and timeframes. One of its advantages is that you can use the RSI on any timeframe of any asset. What does the RSI stand for in stocks? The same thing that it stands for in forex, commodity, and cryptocurrency* markets.

- Simplicity. Despite the wide range of signals, it’s easy to remember them. If you are familiar with other oscillators such as the stochastic oscillator, you will quickly learn how to use the RSI indicator.

- Standard settings. Although you can change the period of the RSI, its standard period of 14 is used in many trading strategies.

- Working signals. The RSI is one of the most popular trading tools. However, the reliability of its signals depends on trader skills and market conditions.

Limitations and False Signals of RSI

Although the RSI is a functional tool, there are some pitfalls traders should consider.

- Weak at trend reversals. The indicator may provide early signals when spotting trend reversal.

- False signals. The relative strength index isn’t a very popular tool in ranging markets.

- Lagging indicator. The RSI is based on past price data, meaning it may be relatively slow to react to sudden movements.

- Overbought/oversold conditions can persist. In strong trends, prices may remain above 70 or below 30 for long periods, leading to premature entries and exits.

Note: The RSI does not determine price direction; it measures the condition of the current move. Its primary value lies in distinguishing continuation conditions from exhaustion conditions.

Final Thoughts

The Relative Strength Index continues to play a central role in technical trading across forex, equities, and cryptocurrency* markets. Its value lies not in reflecting reversals in isolation but in providing insight into the strength and sustainability of price movements. When used alongside trend analysis, volatility measures, and volume indicators, the RSI becomes a powerful component of structured trading strategies.

For traders operating in leveraged CFD and forex markets, proper application involves combining the indicator with broader analytical tools, adapting settings to the trading timeframe, and maintaining disciplined risk management.

You can consider opening an FXOpen account today to build your own trading strategy in over 700 instruments with tight spreads from 0.0 pips and low commissions from $1.50 (additional fees may apply).

FAQ

What Does the RSI Stand For?

RSI stands for relative strength index. It’s a momentum-based indicator that measures the speed and magnitude of price movements.

What Is the RSI Setting?

The only setting of the Relative Strength Index is the period, which reflects the number of past candles used to calculate average gains and losses, affecting how sensitive the RSI is to price changes. The default period is 14, though shorter or longer settings may be applied depending on trading style and timeframe.

How Traders Use the RSI Indicator

The RSI moves between 0 and 100, with >70 meaning the asset is overbought and <30 meaning oversold. It can be used to spot potential market reversals and confirm trend strength.

Is RSI Used in Forex Trading?

Yes. The RSI is widely used in forex to identify pullbacks, confirm trends, and detect divergence signals.

How Do Traders Use RSI Divergence?

Divergence between price and RSI is often used to identify weakening momentum and potential reversals, particularly when confirmed by other indicators or price-structure analysis.

What Is the RSI in Stocks?

The RSI meaning in stocks refers to the same RSI indicator used in other asset classes. It’s used to gauge buying and selling pressure.

Is High RSI Bullish or Bearish?

A high RSI (above 70) signals bullish momentum, suggesting an overbought market and a potential soon downward reversal.

*Important: At FXOpen UK, Cryptocurrency trading via CFDs is only available to our Professional clients. They are not available for trading by Retail clients. To find out more information about how this may affect you, please get in touch with our team.

This article represents the opinion of the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand only. It is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, or recommendation with respect to products and services provided by the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand, nor is it to be considered financial advice.

Crypto World

SBI Holdings Eyes Majority Stake in Singapore-based Coinhako

SBI Holdings, the Tokyo-listed financial group, is intensifying its crypto play by pursuing a controlling stake in Singapore-based Coinhako. Through its wholly owned subsidiary SBI Ventures Asset, SBI signed a nonbinding letter of intent with Holdbuild, Coinhako’s parent company, to inject capital and acquire shares from existing investors. If the deal moves forward, SBI would secure a majority stake and Coinhako would become a consolidated subsidiary, subject to regulatory approvals. Financial terms were not disclosed, and the investment structure remains under discussion. The proposal signals SBI’s broader ambition to build international digital-asset infrastructure beyond a single trading platform, including ventures in tokenized securities and stablecoins.

Chairman and CEO Yoshitaka Kitao framed the development as part of a larger strategy rather than a mere acquisition. He underscored Coinhako as a building block in SBI’s plan to create cross-border rails for digital assets, aligning with efforts to expand tokenized securities, settlement networks, and regulated stablecoins across Asia-Pacific. The Singapore base would offer a licensed footprint in one of the region’s most regulated crypto hubs, potentially smoothing the path for SBI’s foreign-market expansion.

Coinhako, founded in Singapore, operates a regional digital-asset trading platform and related services through Hako Technology, which is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore as a Major Payment Institution. The group also runs Alpha Hako, a virtual asset service provider registered with the British Virgin Islands Financial Services Commission. The exchange’s trajectory has included SBI’s involvement in 2021 via the SBI-Sygnum-Azimut Digital Asset Opportunity Fund, a vehicle that signaled SBI’s willingness to co-invest with established crypto and traditional-finance partners.

Yusho Liu, Coinhako’s co-founder and CEO, framed the alliance as a pathway to scale institutional-grade systems. He emphasized that the partnership would address rising demand for tokenized assets and stablecoins while reinforcing Singapore’s role as a linchpin of the world’s next-generation financial system. The collaboration is seen as a catalyst for deeper liquidity, more robust custody tools, and scalable settlement workflows that could attract regulated participants seeking compliant, cross-border rails.

For SBI, the potential consolidation of Coinhako dovetails with a long-running strategy to broaden its blockchain footprint. The group has pursued tokenization initiatives, payment networks, and other crypto-related businesses for several years. In December 2025, SBI partnered with Startale Group to develop a fully regulated Japanese yen-denominated stablecoin aimed at tokenized asset markets and cross-border settlement, with issuance and redemption handled by Shinsei Trust & Banking and circulation supported by SBI VC Trade, SBI’s own crypto exchange. Earlier in 2025, SBI Group joined forces with Chainlink to build digital-asset tools for financial institutions in Japan and across the Asia-Pacific region. Taken together, these moves illustrate SBI’s intent to connect traditional finance with crypto-native capabilities—spanning custody, liquidity, and programmable settlement rails.

The announcement comes at a time when Singapore’s regulatory framework continues to attract and shape institutional crypto activity. By seeking a licensed base in Singapore, SBI would align with a jurisdiction that has sought to balance innovation with consumer protections and market integrity. The nonbinding nature of the LOI means terms could evolve, and the ultimate path to a definitive agreement will hinge on regulatory scrutiny and the willingness of both sides to align on governance, integration, and capital deployment. The Coinhako deal, if consummated, would place a notable cross-border asset under SBI’s umbrella, potentially accelerating the bank’s ability to service institutional clients seeking regulated access to tokenized assets and stablecoins in Asia’s evolving ecosystem.

Industry observers will watch closely how the transaction might influence Coinhako’s roadmap. A successful consolidation could enable deeper institutional onboarding, more rigorous risk-management protocols, and a broader product set that leverages SBI’s capital, technology, and network—potentially including enhanced liquidity provisioning, custody enhancements, and more formalized cross-border settlement rails. Yet the deal also poses questions about regulatory approvals, competition in Singapore’s exchange landscape, and how a larger SBI-backed entity would interact with local incumbents and market entrants. As with many cross-border crypto ventures, execution risk centers on navigating a complex regulatory matrix and aligning strategic priorities across jurisdictions.

Beyond Coinhako, SBI’s broader blockchain push signals a continuing appetite among major financial groups to blend traditional finance with crypto-native capabilities. The yen-stablecoin initiative with Startale, the Chainlink collaboration, and other partnerships indicate a deliberate roadmap toward tokenized markets, regulated stablecoins, and interoperable networks that can support tokenized securities, digital cash equivalents, and cross-border settlement. If the Coinhako talks crystallize into a binding deal, SBI could gain a foothold in Singapore’s regulated crypto infrastructure, potentially serving as a gateway for further collaborations, licenses, and product launches across the region. The coming months are likely to reveal whether these strategic threads converge into a cohesive, long-term platform strategy or remain a portfolio of exploratory projects that complement SBI’s core banking and payments businesses.

Key takeaways

- SBI Holdings’ subsidiary SBI Ventures Asset signed a nonbinding letter of intent to inject capital into Coinhako and acquire shares from existing investors, potentially giving SBI a majority stake and making Coinhako a consolidated subsidiary pending approvals.

- The terms of the arrangement were not disclosed, and the deal structure remains under discussion, subject to regulatory clearance.

- Coinhako operates a MAS-licensed trading platform in Singapore, with additional services via Alpha Hako in the British Virgin Islands; the exchange has previously attracted SBI investment.

- CEO Yusho Liu described the partnership as a path to scale institutional-grade systems to meet demand for tokenized assets and stablecoins, reinforcing Singapore’s role in the future financial system.

- SBI’s broader blockchain initiatives—yen-stablecoin development with Startale and digital-asset tools with Chainlink—underscore the group’s aim to build cross-border, regulated rails for digital assets in Asia-Pacific.

Market context: The move reflects ongoing consolidation and institutionalization of crypto activities in regulated Asia markets, with Singapore acting as a focal point for cross-border infrastructure and compliant product suites. Regulatory approvals will shape the timeline and scope of any definitive agreement, while the broader market trend toward tokenized assets and stablecoins provides a backdrop for SBI’s expansion strategy.

Why it matters

The potential consolidation of Coinhako under SBI would extend SBI’s footprint beyond traditional financial services into a regulated, cross-border crypto platform. If completed, the transaction could accelerate Coinhako’s ability to scale institutional-grade operations, offering more robust custody, liquidity, and integration with SBI’s broader payments and tokenization programs. The arrangement also signals how large financial groups view regulated hubs like Singapore as launchpads for cross-border crypto activity, not just as regional trading venues but as gateways to tokenized markets across Asia-Pacific.

For Coinhako, the deal could bring additional capital, governance expertise, and access to a global network of financial partners, potentially speeding up product development and regulatory compliance improvements. For Singapore, the move reinforces the city-state’s standing as a regulated center for digital assets, encouraging more collaboration between traditional financial institutions and crypto-native platforms while maintaining stringent oversight to protect market integrity.

From a broader market perspective, SBI’s actions—coupled with its yen-stablecoin initiative and Chainlink collaboration—illustrate a trend among traditional financiers to build multi-faceted ecosystems that blend tokenized assets with regulated stablecoins and cross-border settlement workflows. This could influence how other regional players structure partnerships, custody solutions, and liquidity access as demand for regulated, scalable crypto infrastructure continues to rise.

What to watch next

- Definitive agreement: Sign-off on a binding agreement and disclosure of terms, subject to regulatory approvals.

- Regulatory review: MAS scrutiny and any conditions placed on a potential consolidation and cross-border activities.

- Structural details: Governance, board representation, and integration plans for Coinhako within SBI’s corporate umbrella.

- Product roadmap: Any announced additions to Coinhako’s platform, including tokenized assets or stablecoin-related services linked to SBI’s ecosystem.

- Follow-up disclosures: Additional statements from SBI, Holdbuild, or Coinhako regarding timelines, milestones, or financing rounds.

Sources & verification

- SBI Holdings announces a nonbinding LOI to acquire Coinhako via a press release (pdf): https://www.sbigroup.co.jp/english/news/pdf/2026/0213_a_en.pdf

- Coinhako’s previous SBI investment described in a Cointelegraph article: https://cointelegraph.com/news/sbi-holdings-invests-in-singapore-crypto-exchange-coinhako

- Startale and SBI yen-stablecoin collaboration mentioned in Cointelegraph: https://cointelegraph.com/news/japan-sbi-and-startale-plan-regulated-yen-stablecoin-in-2026-under-new-framework

- SBI Group’s Chainlink partnership to build digital asset tools for APAC: https://cointelegraph.com/news/sbi-group-partners-chainlink-crypto-asia-finance-market

- Background discussion on Asia-Middle East corridor and permissioned-scale approaches: https://cointelegraph.com/news/future-crypto-asia-middle-east-corridor-lies-in-permissioned-scale

SBI bid to anchor Coinhako: implications and next steps

Crypto World

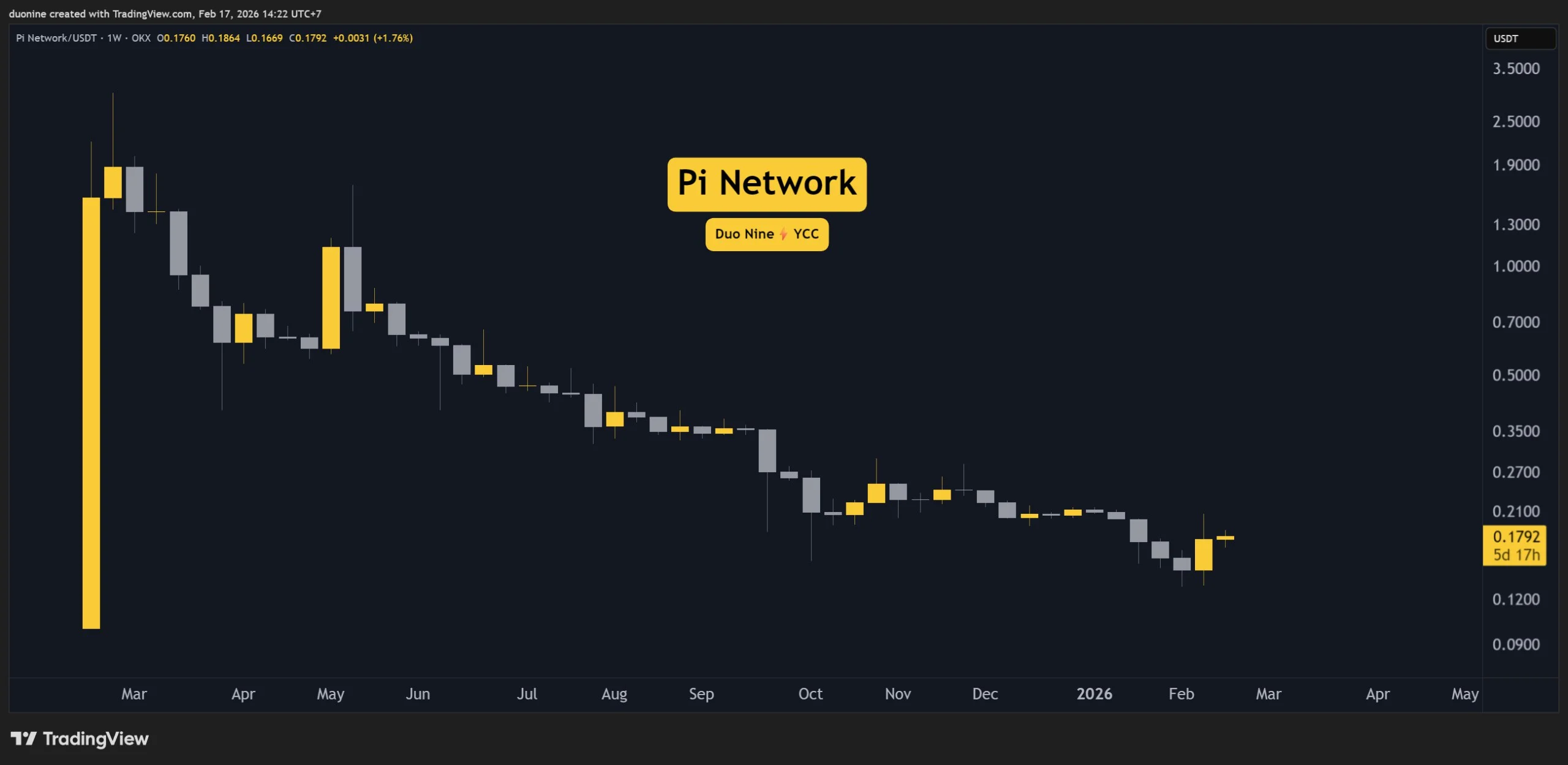

Pi Network (PI) Price Predictions for This Week

PI’s relief rally has arrived! How high will it go?

Pi Network’s native token has shown significant signs of revival in the past several days, surpassing $0.20, where it encountered resistance. What are the most important levels and what’s next?

PI Network (PI) Price Predictions: Analysis

Key support levels: $0.15

Key resistance levels: $0.20

1. PI Finds Support

After a prolonged downtrend, PI has finally found good support above $0.15 and is now keen to test the resistance at $0.20. If successful, then the asset may finally enter a sustained recovery after months of decline.

2. Buying Exploded

Since February 12th, buyers rushed to this cryptocurrency and managed to push its price higher by 50%. This is an impressive rally in such a short period, but it is about to face the resistance at $0.20, which could cut this run short.

3. Daily MACD Turns Bullish

Another positive sign is the daily MACD that turned bullish. The histogram is making higher highs, and there are no signs of weakness at the time of this post. This supports a continuation of this rally, but watch closely the price reaction at $0.20 since sellers could return there.

SECRET PARTNERSHIP BONUS for CryptoPotato readers: Use this link to register and unlock $1,500 in exclusive BingX Exchange rewards (limited time offer).

Disclaimer: Information found on CryptoPotato is those of writers quoted. It does not represent the opinions of CryptoPotato on whether to buy, sell, or hold any investments. You are advised to conduct your own research before making any investment decisions. Use provided information at your own risk. See Disclaimer for more information.

Crypto World

Ethereum price struggles around $2,000 “cold zone”

Ethereum price is hovering just below the $2,000 mark, a level that now feels more like a ceiling than support.

Summary

- ETH has continued to decline in recent sessions, now down 40% monthly.

- A key on-chain metric shows that Ethereum price may be bottoming.

- Technical structure remains bearish unless bulls reclaim the $2,150–$2,200 zone.

Ethereum was trading around $1,981, rising nearly 1% in the past 24 hours. Over the last week, the coin has moved in a tight band between $1,907 and $2,098, reflecting a pause after a period of heavy selling.

The market’s recent slide has been sharp. In the past month, Ethereum (ETH) has dropped about 40% and now sits roughly 60% below its August 2025 record high of $4,946. Activity is slowing down too. Spot trading over the last day totaled $22 billion, down 32% from the previous session, pointing to cooling spot activity.

Derivatives markets show similar caution. Data from CoinGlass shows that total futures volume fell 5.7% to $38 billion, while open interest dropped slightly to $23 billion, down 1.1%. When open interest falls while prices barely move, it usually means traders are cutting back on risk rather than betting on a major breakout.

On-chain data points to a cooling market

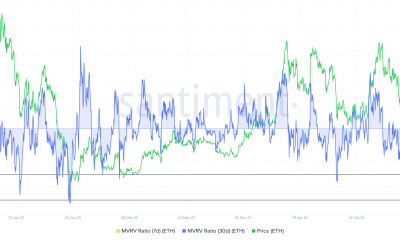

On Feb. 17, analytics firm Alphractal reported that Ethereum’s “Market Temperature” is nearing cold levels. This metric combines the MVRV Z-Score, RVT, and NUPL to assess if the market is oversold or overheated.

In the past, readings near or below zero have often signaled periods of lower speculative activity. Emotional trading wanes, valuations are reset, and unrealized gains decrease.

During previous cycles, markets that stayed in these cold zones for a while often set the stage for longer-term growth as more experienced investors gradually added to their positions.

Separately, a Feb. 16 analysis by CryptoQuant contributor CW8900 found that Ethereum whales are currently sitting on unrealized losses comparable to previous cycle bottoms.

Despite that, they have continued accumulating and now hold their largest balances on record, without having taken profits this cycle. That behavior suggests positioning for a future rally rather than capitulation.

Ethereum price technical analysis

Ethereum is stuck in the $1,900–$2,100 “cold zone.” Tiny daily candles show indecision as the price hovers just below $2,000, showing that traders are cautious.

The chart continues to print lower highs and lows, maintaining the downward trend. Earlier this year, ETH was pushed sharply down from above $3,000, confirming the sell-off, and no higher high has yet been formed to signal a reversal.

The 20-day moving average, which is also the Bollinger Bands’ middle, is above the tokens’ current value. The downward slope of the upper band, which is close to $2,650, strengthens the bearish pressure.

Momentum remains weak. The relative strength index recently fell into oversold territory near 20–25, then bounced to the mid-30s. Still, it has stayed below 50, keeping ETH in a bearish momentum phase.

There has been a slight recent price recovery from $1,800 to $1,900. The move appears to be more corrective than a true rally because there isn’t a significant bullish engulfing candle or volume surge.

Key resistance levels are $2,150–$2,200, $2,650, and $2,800. On the downside, $1,900 offers immediate support. Below that, the recent low is between $1,750 and $1,800, with $1,600 serving as the next significant support area.

If buyers can close daily candles above $2,150–$2,200 and push the RSI above 50, ETH could aim for $2,400. But if $1,900 fails to hold, the path may open toward $1,700–$1,600.

Crypto World

Gold Price Falls to a 10-Day Low

As today’s XAU/USD chart shows, the price of gold has dropped below the lows of 12 February, marking its weakest level in ten days. According to media reports, several factors are weighing on bullion:

→ Easing geopolitical tensions. Safe-haven demand has diminished amid US–Iran and Russia–Ukraine negotiations.

→ Slowing US inflation. This may be prompting traders to reassess expectations for Federal Reserve policy in 2026.

→ The holiday effect. With Presidents’ Day in the US and Lunar New Year celebrations in Asia, trading volumes have declined. In such thin market conditions, prices can become more vulnerable to speculation and abrupt moves.

On 9 February, when analysing gold price movements, we:

→ confirmed the validity of the long-term ascending channel;

→ noted that following a spike in extreme volatility at the turn of the month, the market could begin seeking a new equilibrium;

→ suggested a scenario involving a contraction in price swings on the XAU/USD chart, with the potential formation of temporary balance between supply and demand around the psychological $5k mark.

Indeed, from 9 to 12 February the market formed a consolidation zone slightly above $5k — more precisely, between resistance R1 and local support S1.

Technical Analysis of the XAU/USD Chart

A false bullish breakout (indicated by the arrow) highlighted the bulls’ inability to sustain momentum and effectively became a trap for buyers.

This, in turn, allowed bears to attempt to seize the initiative, resulting in a successful break below the S1 level. Subsequently, the breached level acted as resistance (R2).

Today’s decline on the XAU/USD chart suggests that:

→ bears remain in control, as evidenced by the break of local support S2;

→ a key argument in favour of the bulls may come from the major support at the lower boundary of the long-term channel.

In February, the market has already twice returned within the boundaries of the long-term upward channel. It cannot be ruled out that the price will remain inside it. Notably, if a decisive break above the resistance line (shown in red) occurs, this could reasonably be interpreted as a breakout of a bullish flag pattern.

Start trading commodity CFDs with tight spreads (additional fees may apply). Open your trading account now or learn more about trading commodity CFDs with FXOpen.

This article represents the opinion of the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand only. It is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, or recommendation with respect to products and services provided by the Companies operating under the FXOpen brand, nor is it to be considered financial advice.

Crypto World

Metaplanet stock falls as massive Bitcoin bet backfires

Metaplanet stock edged up just about 3% on the daily chart following the earnings release, but the broader trend remains under pressure. Despite the short-term bounce, the stock is still down roughly 37% over the past month, highlighting investor concerns over the company’s aggressive Bitcoin accumulation strategy and volatile earnings profile.

Summary

- Metaplanet stock rose about 3% after earnings, but remains down roughly 37% over the past month, reflecting continued investor caution.

- The company reported ¥8.9 billion in revenue (+738% YoY) and ¥6.3 billion in operating profit, but posted a ¥95 billion ($619 million) net loss due to Bitcoin-related valuation losses.

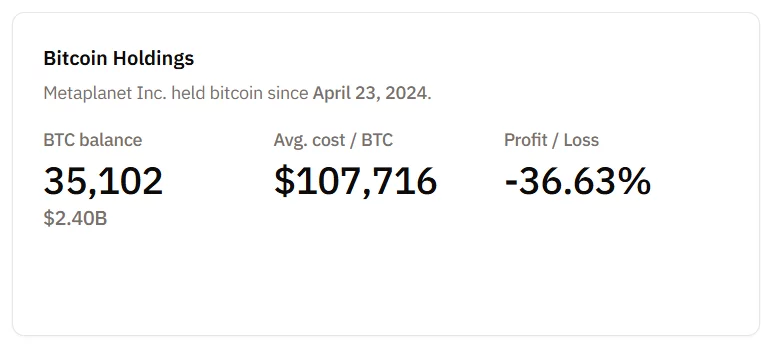

- With 35,102 BTC on its balance sheet, Metaplanet’s share price is increasingly tied to Bitcoin volatility, amplifying both gains and losses.

The Tokyo-listed Metaplanet’s stock dropped from around ¥540–¥550 levels to approximately ¥338, according to the latest monthly chart data. The sharp decline reflects market reaction to the company’s latest fiscal year results and the risks tied to its sizable Bitcoin exposure.

Metaplanet stock reacts to FY results amid Bitcoin volatility risk

In its latest full-year results, Metaplanet reported a dramatic surge in revenue, driven largely by its Bitcoin (BTC) focused operations.

For the year ending December 31, 2025, the company recorded ¥8.905 billion (about $58 million) in revenue, a 738% increase year-over-year, and reported an operating profit of ¥6.287 billion (around $41 million), up nearly 1,700% from the prior year.

Despite the strong operational performance, Metaplanet posted a net loss of roughly ¥95 billion (about $619 million), largely due to a non-cash valuation loss of approximately ¥102.2 billion (about $660 million) on its Bitcoin holdings as prices declined during the reporting period.

As accounting rules require digital asset holdings to reflect market value changes, swings in BTC prices can heavily distort bottom-line results.

Bitcoin-heavy strategy amplifies volatility

Metaplanet has rapidly scaled its crypto treasury, ending 2025 with 35,102 Bitcoin, up from just 1,762 BTC the year before, a roughly 1,892% increase, making it one of the largest corporate holders globally and the largest in Japan.

That Bitcoin stack now represents a core part of its balance sheet and revenue model, with much of its income tied to Bitcoin-related trading and yield activities.

However, the sharp correction in Bitcoin prices over recent months has turned what once were unrealized gains into deep paper losses, eroding investor confidence and weighing on the share price.

Metaplanet’s approach effectively makes the stock a leveraged play on Bitcoin itself, which has heightened market sensitivity as the crypto asset swings.

For traders and shareholders, the near-38% monthly drop underscores the risk of coupling equity valuation tightly to a volatile crypto asset, even when underlying operations are growing. Until Bitcoin stabilizes, Metaplanet’s share performance will likely continue to track broader crypto market sentiment.

Crypto World

Monero price confirms bullish reversal pattern, eyes rebound to $420

Monero price confirmed a bullish reversal pattern as dip buyers capitalized on a recent drop. XMR now eyes a potential rally to as high as $420 over the coming weeks, as demand for privacy solutions is on the rise.

Summary

- Monero price has broken out of a falling wedge pattern on the daily chart.

- Demand for privacy tokens to circumvent government surveillance, and their large-scale usage in illicit markets has been benefiting XMR.

According to data from crypto.news, Monero (XMR) price rose nearly 9% to an intraday high of $344 on Tuesday, Feb. 17, while its market cap moved back above $6.3 billion.

Dip buyers took an interest in the token after it fell to a yearly low of $284 earlier this month. While it has retraced some of the losses, XMR still lies 57% below its yearly high of $788.50.

Now, on the daily chart, Monero price has confirmed a breakout from a falling wedge pattern, one of the most popular bullish reversal patterns formed by two converging and descending lines. Historically, a breakout from such patterns has been followed by days of consistent uptrend before losing momentum.

The technical breakout gains strength from a bullish MACD crossover and an RSI that is trending close to oversold levels.

Hence, the next key resistance level for Monero lies at $381, the 200-day EMA, which would serve as the final hurdle to validate a long-term trend reversal.

Breaking above this level could offer bulls the support needed to test the psychological resistance level at $420. XMR price breakouts have stalled around this area in past market cycles.

There are multiple catalysts that are driving the Monero rebound today and could continue to act as a tailwind in the days ahead.

First, investors seem to be rotating capital from other privacy-centric tokens such as Zcash (ZEC) and Dash (DASH) as they rebalance their portfolios. Zcash, for instance, has lost much of its investor appeal after its core development team resigned last month.

Second, Monero is also benefiting from a renewed demand for privacy tokens, especially as regulators across the globe are tightening oversight. New reporting standards across many jurisdictions now require platforms to share user identities and transaction histories with authorities, which has sparked concerns over the sector’s privacy ethos.

At the same time, recent reports suggest XMR has become a popular means of payment across darknet marketplaces, where large-scale transactions are creating an additional source of demand.

Disclosure: This article does not represent investment advice. The content and materials featured on this page are for educational purposes only.

Crypto World

Will Hyperliquid price crash as bearish crossover forms and revenue drops?

Hyperliquid price has remained in a downtrend over the past two weeks, dropping nearly 20% since its yearly high as network revenues have slumped. Will the token crash now that it has confirmed a bearish crossover?

Summary

- Hyperliquid price has fallen 25% from its yearly high.

- Bitcoin’s ongoing downtrend and a cooldown in network activity have hurt the token’s price.

- A bearish MACD crossover on the daily chart could spell more trouble for the token in the coming sessions.

According to data from crypto.news, Hyperliquid (HYPE) price fell 25% to a monthly low of $28.5 on Wednesday last week after it hit a yearly high of $37.8. It has since managed to retrace some of its losses, exchanging hands at $30.2 when writing.

Hyperliquid price has been in a downtrend due to lingering bearish sentiment in the crypto market after Bitcoin (BTC), the bellwether crypto asset, fell through multiple key psychological resistance levels one after the other, dampening investor appetite for other major cryptocurrencies.

The token’s price has fallen amid weakness in key fundamental metrics. Data from DeFiLlama shows that the weekly revenue generated by the network has dropped 55% to $11.8 million last week, while the total value locked in the platform has dropped from its yearly high of $4.7 billion to $4.24 billion.

A drop in TVL and revenue generated on the network suggests that trading activity on the exchange is cooling off. Specifically, a drop in revenue generated by the platform also lowers the total amount of capital the platform gets to buy back and burn tokens from the market. This reduction in deflationary pressure makes it harder for the price to recover while sell-side pressure remains high.

The short-term outlook for Hyperliquid price also appears to be bearish when looking at its daily chart. Notably, the MACD lines have confirmed a bearish crossover with growing red histograms signaling that selling pressure seems to overwhelm buyers.

HYPE’s daily RSI has also entered into a descending channel formation and was close to dropping below the neutral threshold. Furthermore, HYPE price was drawing closer towards the 38.2% Fibonacci retracement level at $28.4, drawn from last year’s April low to September high.

A break below this key psychological level risks a move toward $21.10. Between the bearish technical crossover and underwhelming weekly revenue, the token is trending toward the target nearly 20% lower than current prices.

On the contrary, if HYPE manages to bottom and rebound from $28.4, it could retrace back toward its yearly high of $37.8. This would likely require a broader recovery in the crypto market as well, alongside a resurgence in trading volumes on the Hyperliquid platform to drive the necessary demand.

Disclosure: This article does not represent investment advice. The content and materials featured on this page are for educational purposes only.

Crypto World

Zerolend Shutters as Founder Says It’s ‘No Longer Sustainable’

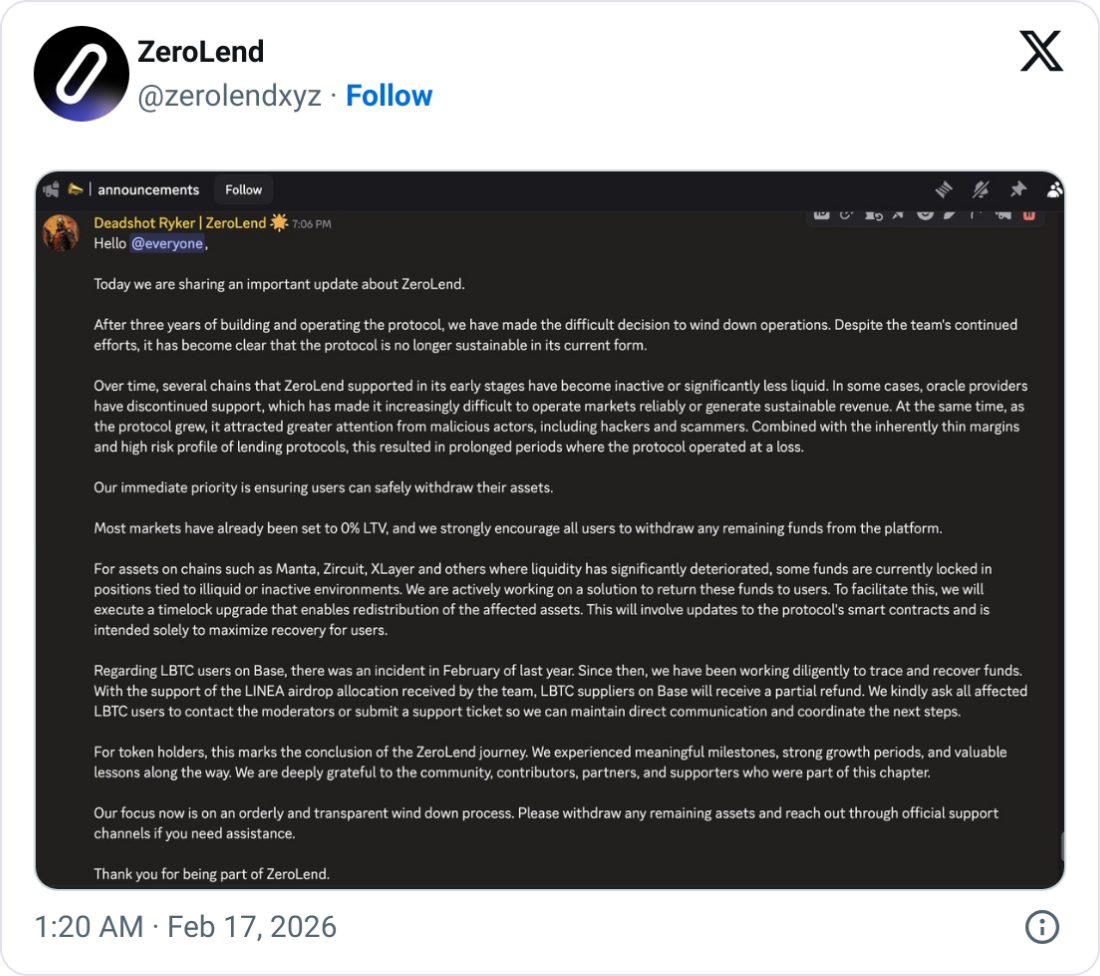

Decentralized lending protocol ZeroLend says it is shutting down completely after the blockchains it operates on have suffered from low user numbers and liquidity.

“After three years of building and operating the protocol, we have made the difficult decision to wind down operations,” ZeroLend’s founder, known only as “Ryker,” said in a post the protocol shared to X on Monday.

“Despite the team’s continued efforts, it has become clear that the protocol is no longer sustainable in its current form,” he added.

ZeroLend focused its services on Ethereum layer-2 blockchains, once touted by Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin as a central part of the network’s plan to scale and remain competitive.

However, Buterin said earlier this month that his vision for scaling with layer 2s “no longer makes sense,” that many have failed to properly adopt Ethereum’s security, and that scaling should increasingly come from the mainnet and native rollups.

ZeroLend operated at loss due to illiquid chains, says Ryker

ZeroLend’s Ryker said the reason for the shutdown is that several blockchains the protocol supported “have become inactive or significantly less liquid.”

He added that in some cases, oracle providers — services that fetch data and are often crucial to running protocols — have stopped support on some networks, making it “increasingly difficult to operate markets reliably or generate sustainable revenue.”

“At the same time, as the protocol grew, it attracted greater attention from malicious actors, including hackers and scammers,” Ryker said. “Combined with the inherently thin margins and high risk profile of lending protocols, this resulted in prolonged periods where the protocol operated at a loss.”

He added that the protocol will ensure users can withdraw their assets, adding, “We strongly encourage all users to withdraw any remaining funds from the platform.”

Ryker said some user funds may be locked on blockchains that have seen “significantly deteriorated” liquidity, and ZeroLend will upgrade the protocol’s smart contracts with the aim of redistributing stuck assets.

Related: TradFi giant Apollo enters crypto lending arena via Morpho deal

He added that ZeroLend has also been working to trace and recover funds tied to an exploit in February last year, where protocol users of a Bitcoin (BTC) product on the Base blockchain were exploited after an attacker drained lending pools.

Ryker said that suppliers of the product affected by the incident will receive a partial refund funded by an airdrop allocation received by the ZeroLend team.

At its height in November 2024, ZeroLend commanded a total value locked of nearly $359 million, but that has since sunk to $6.6 million, according to DefiLlama.

The ZeroLend (ZERO) token has fallen by 34% in the last 24 hours in reaction to the protocol’s shutdown and has also lost nearly all its value since hitting a peak of one-tenth of a cent in May 2024, according to CoinGecko.

Magazine: Ethereum’s Fusaka fork explained for dummies — What the hell is PeerDAS?

Crypto World

UK crypto rules moving too slowly to secure global hub status, says FCA-registered stablecoin Issuer Agant

The U.K.’s crypto regulatory framework is moving in the right direction, but not fast enough to support the country’s ambitions of becoming a global digital asset hub, Andrew MacKenzie, CEO of sterling stablecoin developer Agant, told CoinDesk.

The government has repeatedly pledged to position London as a center for global crypto and digital asset activity. However, comprehensive legislation governing stablecoins and wider crypto activity is expected to be approved by parliament only later this year and won’t come into force until 2027.

MacKenzie said this timeline contradicts the government’s goal of remaining globally competitive within the industry.

“I think the most damaging thing today has been the time that it’s taken to get to where we are just now,” MacKenzie said in an interview at Consensus Hong Kong. “People just want clarity … If there’s anything I’d like to see from the regulators, it’s just an acceleration in the pace with which we can do things.”

The London-based company recently joined the small group of cryptoasset businesses registered with the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) under money laundering regulations, an approval process widely regarded as one of the most stringent globally. FCA registration is a prerequisite for operating certain cryptoasset activities in the U.K., and the process has earned a reputation for being both exacting and slow.

A hard-won regulatory milestone

For Agant, which plans to issue a fully backed pound sterling stablecoin called GBPA, the registration signals institutional intent rather than a retail crypto push. The company has positioned the token as infrastructure for institutional payments, settlement and tokenized assets.

The firm maintains active dialogues with the Treasury, the FCA and the Bank of England, MacKenzie said, describing engagement as constructive, but iterative.

“There are certain aspects that we don’t like, and we’re very vocal about them,” he said, referring in part to proposed limits within the Bank of England’s stablecoin framework.

Still, he said, regulators are listening.

“The most promising aspect when we speak to regulators is the fact that they’re willing to implement changes if there’s true justification there.”

Stablecoins as a tool, not a threat

When asked if he viewed European central banks’ and U.S. private banks’ opposition to stablecoins as a problem for the future of his project, MacKenzie dismissed their concerns over financial stability and unfair competition, saying stablecoins can strengthen sovereign monetary reach.

“When you see the penny drop with central bankers, you realize that this is actually an amazing way for them to export sovereign debt,” he said. By issuing a pound-pegged stablecoin, firms like Agant could distribute digital pounds globally, increasing exposure to sterling-denominated assets and potentially lowering funding costs. “We can go and sell pounds globally,” he said. “The cost of carry for the central bank is just reduced somewhat.”

Rather than eroding sovereignty, he said, properly structured stablecoins can extend it.

For commercial banks, the concern is that if consumers hold funds in stablecoins rather than depositing them, they could lose their ability to lend.

MacKenzie rejected that premise. “I don’t think it is a valid argument. What it really brings to the table is that banks need to become more competitive.”

Credit would not disappear, he added, but could shift toward alternative providers if incumbent banks fail to adapt. In that sense, stablecoins may increase competition in financial services rather than diminish credit availability.

UK banks shift from skepticism to acceleration

Bankers in the U.K. are paying closer attention to cryptocurrency projects, MacKenzie said. Conversations have escalated up the hierarchy.

“It’s now a C-suite conversation,” he said. “There’s an exponential acceleration to banks’ adoption of blockchain technology.”

Banks increasingly recognize efficiencies in programmable reconciliation, instant settlement and cross-border interoperability, he said. Even though the transition may take decades, as it did with the shift to digital banking, momentum is building.

“The banks themselves have expressed they see this as a 30-year transition.”

If the U.K. intends to compete with faster-moving jurisdictions in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, time may prove the most critical variable.

Whether Britain can convert ambition into leadership may depend less on regulatory design and more on how quickly policymakers move.

“Zoom out and look at the macro,” MacKenzie said. “Nothing is set in stone.”

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoBig Tech enters cricket ecosystem as ICC partners Google ahead of T20 WC | T20 World Cup 2026

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoSpaceX’s mighty Starship rocket enters final testing for 12th flight

-

Video17 hours ago

Video17 hours agoBitcoin: We’re Entering The Most Dangerous Phase

-

Tech2 days ago

Tech2 days agoLuxman Enters Its Second Century with the D-100 SACD Player and L-100 Integrated Amplifier

-

Video4 days ago

Video4 days agoThe Final Warning: XRP Is Entering The Chaos Zone

-

Tech5 hours ago

Tech5 hours agoThe Music Industry Enters Its Less-Is-More Era

-

Crypto World7 days ago

Crypto World7 days agoBlockchain.com wins UK registration nearly four years after abandoning FCA process

-

Crypto World3 days ago

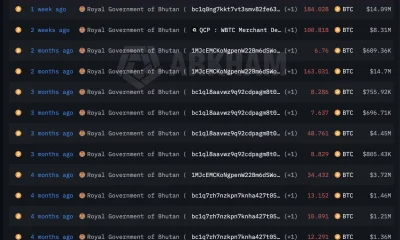

Crypto World3 days agoBhutan’s Bitcoin sales enter third straight week with $6.7M BTC offload

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoPippin (PIPPIN) Enters Crypto’s Top 100 Club After Soaring 30% in a Day: More Room for Growth?

-

Video5 days ago

Video5 days agoPrepare: We Are Entering Phase 3 Of The Investing Cycle

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoThe strange Cambridgeshire cemetery that forbade church rectors from entering

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoBarbeques Galore Enters Voluntary Administration

-

Crypto World6 days ago

Crypto World6 days agoCrypto Speculation Era Ending As Institutions Enter Market

-

Crypto World5 days ago

Crypto World5 days agoEthereum Price Struggles Below $2,000 Despite Entering Buy Zone

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoWhy was a dog-humping paedo treated like a saint?

-

NewsBeat2 days ago

NewsBeat2 days agoMan dies after entering floodwater during police pursuit

-

Crypto World3 days ago

Crypto World3 days agoBlackRock Enters DeFi Via UniSwap, Bitcoin Stages Modest Recovery

-

NewsBeat3 days ago

NewsBeat3 days agoUK construction company enters administration, records show

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoWinter Olympics 2026: Australian snowboarder Cam Bolton breaks neck in Winter Olympics training crash

-

Crypto World4 days ago

Crypto World4 days agoKalshi enters $9B sports insurance market with new brokerage deal