Long before Apple became synonymous with Steve Jobs’ product launches and minimalist design philosophy, the company’s survival depended on a quieter figure operating behind the scenes.

An InfoWorld article published on July 18 1983 described Mike Markkula as the person who turned Apple from a clever engineering experiment into a real business — the man who wrote its first proper business plan, secured crucial funding, and helped build the company that would later dominate consumer technology.

The article opens with blunt praise from people inside the industry. “Markkula is what made Apple real,” said Chuck Peddle, president of Victor Technologies.

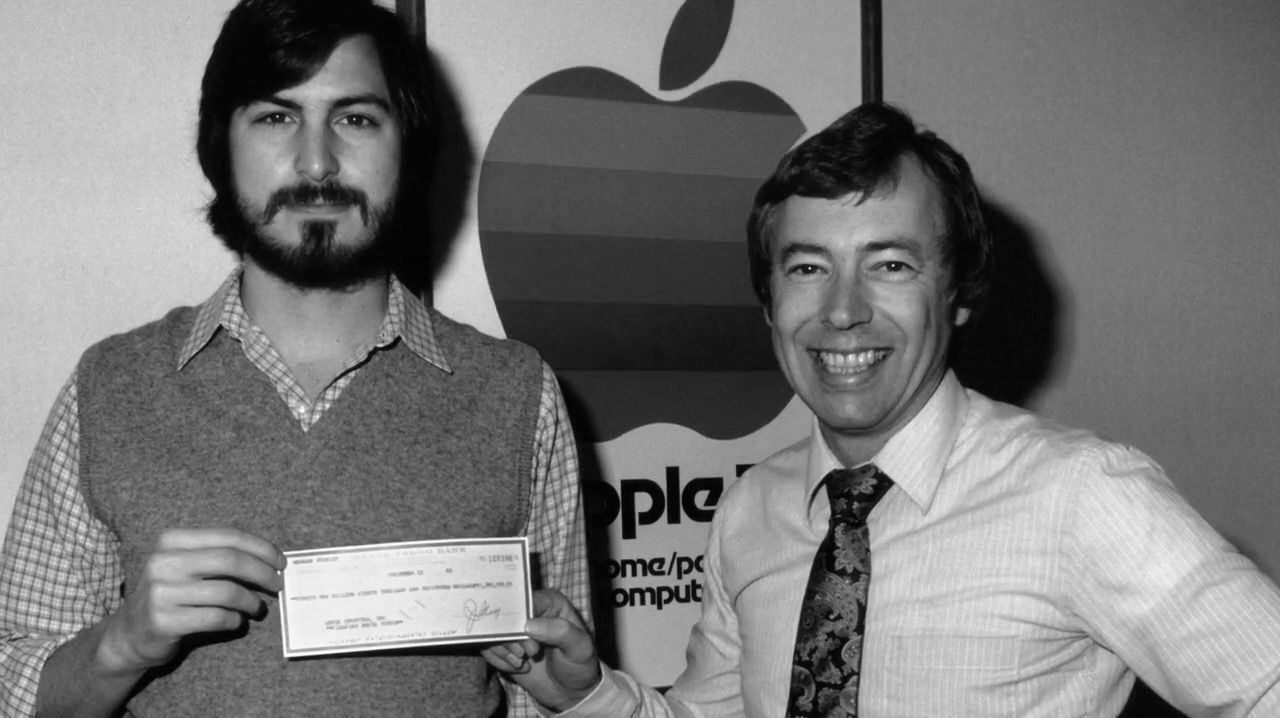

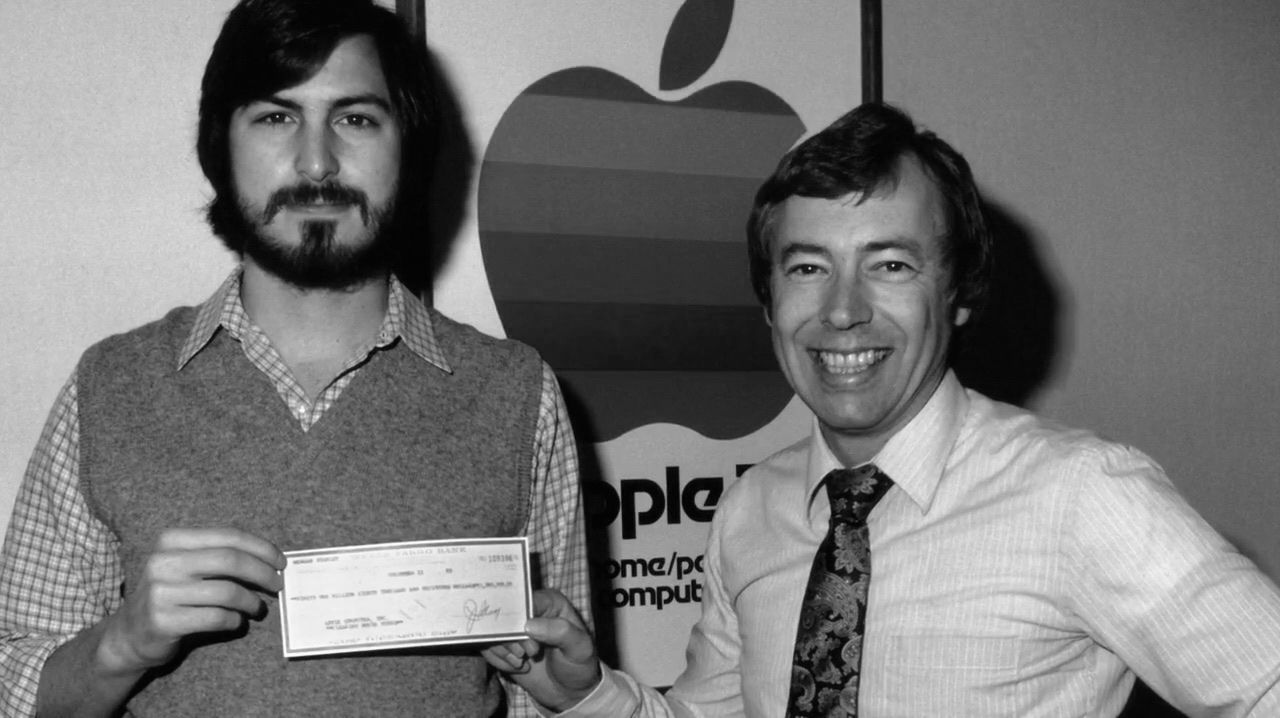

Even Steve Jobs, already a prominent personality by that stage, was quoted saying, “It became very clear that what we really wanted was Mike. So we split the pie three ways.”

Apple’s first business plan

In the mid-1970s, personal computing was crowded with enthusiastic startups that rarely lasted. InfoWorld noted that “dozens of small companies started up,” but many disappeared due to what early industry figures called “‘entrepreneur’s disease’ — the inability to run a business successfully.”

Against that backdrop, Apple’s rise stood out. According to the 1983 InfoWorld article, “the difference with Apple was the man who wrote the company’s first business plan, Mike Markkula.”

That business plan did more than organize ideas. It gave Apple credibility. Markkula had recently retired from Intel, with investments that meant he “could afford to take it easy.” But after visiting Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs’ garage operation, he volunteered: “I’ll help you do a business plan.” He added that he might invest money, or as the article quoted him, “You’ve gotten a few weeks of my time for free.”

Early Apple engineer Rod Holt told InfoWorld that Markkula “got hooked,” adding, “He worked harder than anybody. He was working till two in the morning day in and day out.”

The portrait that emerges is not of a passive investor but of someone actively shaping the company’s direction during its most fragile stage.

One of Markkula’s most lasting contributions was marketing. The InfoWorld article explained that he brought expertise that other early computer companies lacked, placing ads in publications with affluent or intellectually curious readers, including Playboy and Scientific American.

First in the phone book

In a market where many competitors still sold computers as technical tools, Apple began to appear as something more — a product for ordinary people.

Branding played a key role. Markkula resisted changing the company’s name, and InfoWorld recorded his reasoning: “We knew we would be first in the phone book.” He also recognized the psychological impact of language.

The article noted that the word Apple had “positive connotations to people who were turned off by the word computer,” and that the unusual pairing of “Apple” and “computer” would help people remember it.

From a modern perspective, this decision looks remarkably forward-thinking. Today’s tech companies obsess over branding strategy, but in the mid-1970s that approach was far from common in Silicon Valley’s engineering-first culture.

Markkula understood that adoption depended on familiarity as much as technical performance, a lesson still echoed in consumer tech marketing.

The InfoWorld piece also highlighted his influence on product presentation. While debates took place over switching processors, Markkula encouraged keeping Wozniak’s design and, together with Jobs, pushed for “an elegant plastic case as part of the package.”

At a time when many computers arrived as exposed boards intended for hobbyists, packaging mattered. The machine was a finished product, not a kit.

Markkula’s involvement extended beyond business and aesthetics. He enjoyed experimenting with software and wrote a checkbook program himself. His frustration with cassette storage reportedly led him to suggest that Wozniak design a disk drive for the Apple. That detail is a clear indication of how deeply he engaged with the products, rather than simply managing from a distance.

Expert systems

Markkula was calm and businesslike but occasionally bold in motivating staff. At one point, he promised to take every employee to Hawaii if Apple achieved $100 million in quarterly sales in 1981. The company fell slightly short, but Markkula still granted them an extra week’s vacation.

Today that seems like an early example of startup culture incentives long before such practices became common.

Financially, his impact was undeniable. As chairman, he secured a line of credit from Bank of America and attracted venture capital from Venrock Associates. These moves gave Apple the stability that many competitors lacked.

By 1982, Apple’s annual sales had risen to over $500 million, and the future tech giant had entered the Fortune 500 list.

Viewed through a modern lens, Markkula’s role feels especially relevant. Contemporary startups often rely on experienced operators who complement technical founders by bringing commercial discipline.

In today’s vocabulary, he would be called a strategic operator or growth architect. In 1976, he was simply the person who knew how to make a company work.

Markkula’s legacy

The 1983 article came at a transitional moment. In the same InfoWorld issue, Apple announced a new disk operating system, ProDOS, to boost the power and portability of Apple II software, and details of the Macintosh were beginning to leak out.

Most notably, Mike Markkula had stepped aside as president, making room for John Sculley, whose arrival signaled the start of a new phase for the company.

Despite the change at the top, InfoWorld insisted that Markkula “must be acknowledged as the person who distinguished Apple from the other early personal-computer firms.”

That recognition is key, because the public narrative of Apple would soon become dominated by Jobs’ larger-than-life image.

Markkula’s role might be largely forgotten now, his name unknown by today’s Apple audience, but his legacy sits in the spaces between the iconic moments — in the business plan, the funding agreements, the naming decisions and the strategic marketing choices that allowed the company to survive long enough to reinvent itself repeatedly.

The line that defines the story best may still be the simplest one. At the start of Apple’s journey, when stakes were high and futures uncertain, “what we really wanted was Mike.” More than forty years later, the quote serves as a reminder that behind every tech legend is someone who made the business real in the first place.

Follow TechRadar on Google News and add us as a preferred source to get our expert news, reviews, and opinion in your feeds. Make sure to click the Follow button!

And of course you can also follow TechRadar on TikTok for news, reviews, unboxings in video form, and get regular updates from us on WhatsApp too.

Ruslan Nagimov, the principal infrastructure engineer for Cloud Operations and Innovation at Microsoft, stands near the world’s first HTS-powered rack prototype.Microsoft

Ruslan Nagimov, the principal infrastructure engineer for Cloud Operations and Innovation at Microsoft, stands near the world’s first HTS-powered rack prototype.Microsoft