Business

Your car is about to become part of the internet

There is something peculiarly unsettling about talking to someone who has spent decades working on a technology that might render millions of people obsolete. Sven Beiker, Managing Director of Silicon Mobility and a lecturer on the automotive industry at Stanford University, is unfailingly polite about it all. He speaks with the careful optimism of a man who has thought deeply about what he is helping to build, and who is not entirely comfortable with where it might lead.

We met on the sidelines of the Abu Dhabi Autonomous Summit in November, where the great and good of the self-driving vehicle industry are gathered to celebrate their progress. There is much to celebrate: robo-taxis that once seemed like science fiction are now ferrying passengers around Phoenix, San Francisco, Austin and Las Vegas. In China, they operate in Beijing, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Wuhan and Shanghai. Now Abu Dhabi itself is joining the club.

Beiker, a German automotive engineer who has lived in Silicon Valley for over 20 years, knows this world intimately. His background is in autonomous systems, which he has worked on “as an academic, as an engineer and as a consultant”. When I ask whether he approaches the automated future with optimism or pessimism, he replies without hesitation: “Optimism, for sure, but in a measured way, because there are challenges. But I think the opportunities outweigh the risks.”

He tells me he visited in China in August, travelling to Beijing, Shenzhen and Guangzhou. What he found surprised him. “I was really surprised with the level of performance and skill of driverless vehicles. I had not expected it to that extent,” he says. “As a Westerner and a German automotive engineer, I have huge appreciation for the Waymo vehicles” – the Alphabet-owned self-driving cars that were first in the game. “I had not thought the Chinese companies were at the same level, but they are. In my view, they are at the same level.”

When I press him on whether the Chinese are actually ahead, he is careful. “I’m not sure I can say ahead. What I would say makes them distinct from what I see in the United States is that there are three companies, Pony Ai, Baidu and WeRide. They are all at a very similar level.” He points out in the United States, it is mostly only Waymo. “So, in that sense, with the number of companies, China might be ahead.”

People increasingly speak of AI and automation as a race, but Beiker challenges this framing. “For a race, you have typically a clear start and finish line. A start? That is basically the status quo transportation as we know it. But what is the finishing line? Is the finishing line the first successful deployment? Is it a certain percentage of traffic that is covered? Is it all driverless vehicles, and human-driven cars are no longer allowed?” The comparison to the space race of the 1950s and 60s does not hold, he argues, because there is no equivalent of putting a man on the moon. Instead, there is “certainly a competition for strategy, prestige and in the end, market share”.

Abu Dhabi, he says, has considerable advantages. The fair weather helps, because “the sensors have problems with heavy rain, snow, fog”. Relatively new infrastructure and compact geography also make deployment easier. And then there is “a welcoming government – a welcoming business environment that attracts industry”. He draws a parallel with Phoenix, and also with some Chinese cities. “When you go to the autonomous driving test area south of Beijing, it’s basically a huge office park and commercial area. It’s more or less a chess board of infrastructure. And that is definitely supportive to launching such technology. Whereas, if you go to Rome or Paris, very different.”

I confess to Beiker that I like driving, and ask whether the days of doing it are numbered. He says: “I wouldn’t say the days are numbered and it’ll be gone anytime soon. There will definitely be more and more automation, but the point that you will not be able to drive yourself anymore, I think that’s pretty far in the future – 30 years plus.”

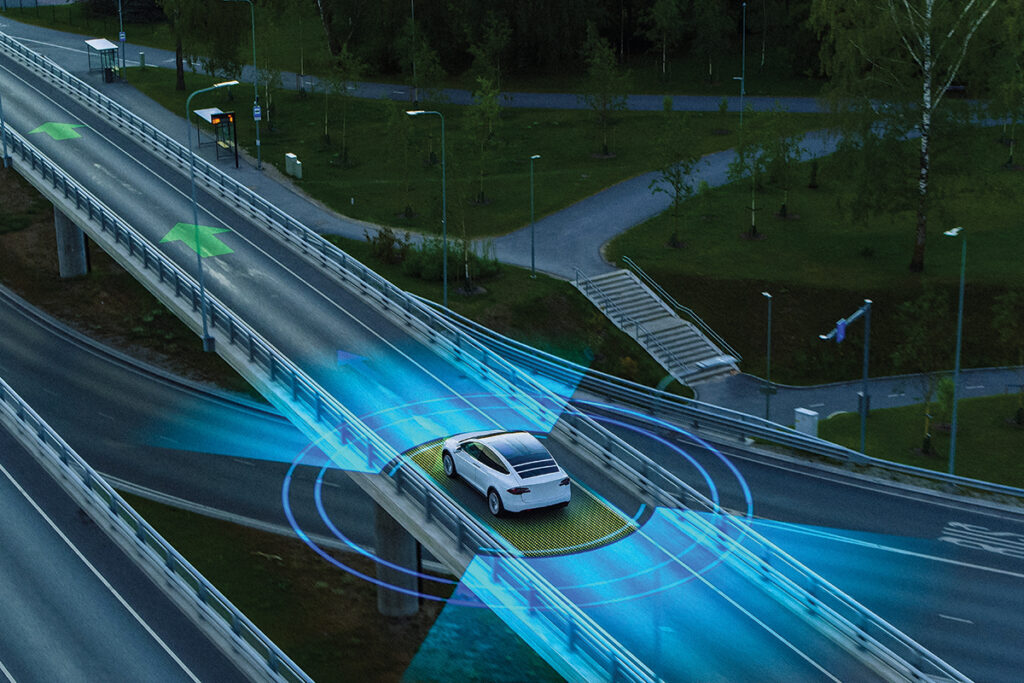

But what comes after the self-driving car itself? What is the next revolution? Here, Beiker offers something genuinely fascinating. “In my view, the self-driving car is in a way a physical extension of the Internet. The Internet moves around data and information. Self-driving cars and trucks move around people and goods. Once you integrate all of this, this is when the magic of something new will happen.”

The analogy is more than superficial. “Some of the thinking and the concepts of network theory from the internet apply to transportation when it becomes automated. Because then it becomes a question of throughput, of availability, of nodes, of scheduling and storage. Where do you put the vehicles when you don’t need them? When do you deploy them, and at what time?…”

I tell him it sounds like he’s describing the ultimate Internet of Things and he is quick to add a caveat.

“Transportation will always be a physical undertaking, until we invent tele-transportation. The compute power will only help so much, because we cannot compress the medium that we are moving around. We cannot compress people to make it more efficient.”

He points out, too, that the business case for the automation of transport still doesn’t exist. “For now, what we see is it’s replacing human drivers. One may ask the question, okay, fine, but why are we doing this?” The companies pitch it as saving costs, “but guess what? For now, there are not actually fewer humans involved, because there are still humans overseeing those vehicles, maintaining these vehicles, servicing those vehicles, cleaning those vehicles. The business case is not there yet.”

He draws on the experience of two decades living in California to explain what is happening. “This is a typical Silicon Valley innovation,” he says. “Deploy a technology, build a new market – the business model is there more as an afterthought, once you figure out what to do with it.” He adds the companies behind these new technologies are “typically investing billions of dollars to bring this technology to the roads. The business case is not really there yet. It’s a bet on the future, that at some point things change completely.”

Does he ever worry about where all of this is headed? He says he does, but on balance is optimistic. He admits he worries sometimes about the extent to which artificial intelligence is being regulated. “I do have concerns that it’s not always deployed and managed responsively.”

He adds it is the inherent tension that exists between inventors and investors that might threaten to cause these new technologies to be rolled out more rapidly than society can absorb them.

“Typically, there’s great minds with outstanding ideas and capabilities – potentially genius. And then there’s the investors. That can become an explosive mix. This is what does make me concerned – that society is exposed to something we might not be able to handle, because the investors want to scale it up. If you invest a couple of billion dollars into something, you want to see a return on investment. This industry typically only grows through scale. That means you need to push AI into everything. What does that mean? It’s a bit scary.”

The technology itself may be manageable. The question is whether the combination of brilliant minds, vast capital and the pressure to scale can be controlled. As our cars become nodes on a vast physical internet, we are about to find out.