Football

Mbappé

From Paris suburbs to the pinnacle of football, a look at a once-in-a-generation talent.

Source link

Football

Guardiola: Chasing Perfection

How and why has Pep Guardiola been able to revolutionise football?

Source link

Football

Listen: What next for Hearts?

Thomas Duncan, Ryan Stevenson and Simon Donnelly discuss the big Scottish football news

Source link

Football

WSL agrees new £45m sponsorship deal with Barclays

A new three-year agreement has been reached with Barclays to remain the title sponsor of the Women’s Super League and Women’s Championship.

The deal is understood to be in the region of £15m a year, including investment and marketing, double the previous arrangement which runs out at the end of this season.

It is the first major contract secured by the WSL’s new takeover company, Women’s Professional Leagues Limited (WPLL).

Barclays became the title sponsors in 2019 and the renewal is said to be the biggest deal in women’s domestic football.

There has been a continual increase in viewing figures and attendances across the WSL over the past few years.

WPLL chief executive Nikki Doucet said: “Barclays has been a leading light when it comes to supporting women’s football and they become a founding partner for WPLL as we embark on a transformational journey to grow the game.

“This record multi-year investment demonstrates long-term commitment and is important because it provides positive endorsement and increased support for what we are trying to accomplish.”

Barclays has also extended its partnership with the Premier League, agreeing a new four-year deal.

Football

Hungary’s Euro 2024 ambitions and Viktor Orban’s politics

His football project has added a new historical layer to Hungary, where communist-era tower blocks, grand Austro-Hungarian buildings, and Ottoman baths betray a tumultuous past.

If the Pancho Arena is closest to his heart, the national stadium in Budapest is the biggest example of his and the government’s adoption of football.

Similar to Bayern Munich’s Allianz Arena in size and design, but built at three times the cost, it stands on the former site of the rickety, historic Nepstadion.

In an otherwise unremarkable 1-0 friendly win over Estonia there in March 2023, the most dramatic moment came as a single, repeated phrase boomed out of the public address system.

The stadium’s tannoy announcer chanted: “Down with Trianon, down with Trianon.”

The Trianon Treaty was the agreement that reduced Hungary’s size by two-thirds in 1920.

Millions of ethnic Hungarians still reside within pre-Trianon Greater Hungary – the old imperial territory that existed before Austria-Hungary’s defeat in World War One.

The stadium announcer was only following Orban’s lead. Four months before, the prime minister had posted video of himself congratulating winger Balazs Dzsudzsak on his retirement from international duty.

Around Orban’s neck was a scarf featuring an image of Greater Hungary.

Ukraine, invaded by Russia earlier that year, summoned Hungary’s ambassador to explain another apparent claim on its territory. Romania, which took over Transylvania in 1920 and is still home to 1.2 million ethnic Hungarians, voiced “firm disapproval” of Orban’s gesture.

For many Hungary fans though, it tapped into a deep sense of historical injustice.

As the public address system denounced the loss of former Hungarian territories, as war raged over the border in Ukraine where some 200,000 ethnic Hungarians reside, no discernible surprise was visible among the crowd, so blurred have the lines between football and incendiary nationalist politics become in Orban’s Hungary.

“The essence of the football is like the essence of politics,” said Orban, who has been the most prominent pro-Russian voice in the European Union.

“Because the question is not where the ball is now – everybody can see where the ball is now – but the question is where the ball will be…

“If you understand earlier than others what will happen, you can react first and you can win.”

Football

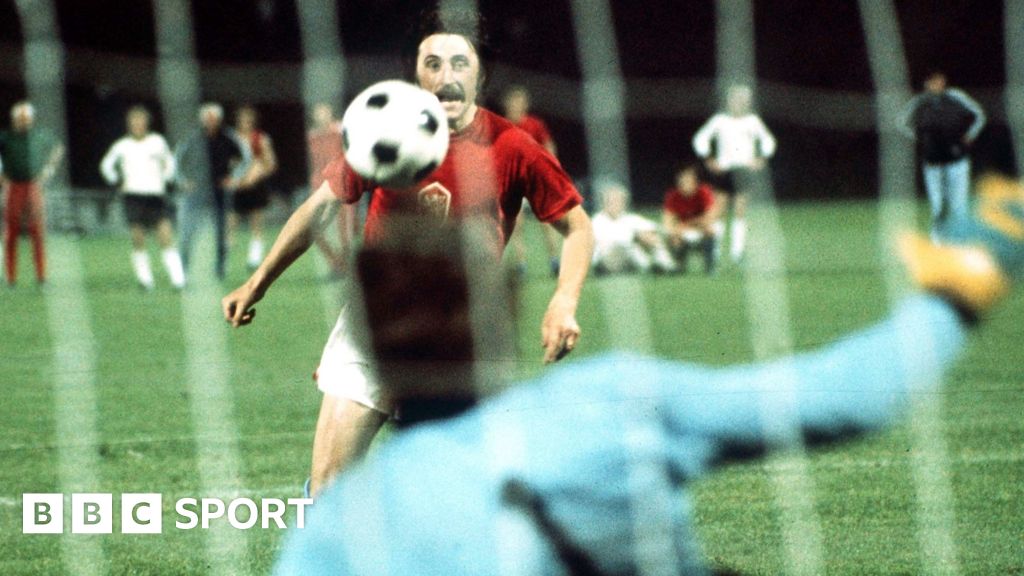

Antonin Panenka: The Euro 1976 penalty that killed a career and birthed a feud

Back home, Panenka had been involved in another, almost daily, penalty contest.

After training at his Prague club side Bohemians, Panenka and goalkeeper Zdenek Hruska would stay behind to practise spot-kicks.

It was a very personal duel. Panenka would have five penalties – he would have to score all five, Hruska would have to save just one. Whoever lost would buy their post-training beer or chocolate.

“I was constantly paying him,” says Panenka.

“So in the evenings I would think up ways to beat him – that’s when I realised that as I ran up the goalkeeper would wait for the last second and then gamble, diving to the left or the right.

“I thought: ‘What if I send the ball almost directly into the centre of the goal?’”

Panenka tried it. He found that introducing another possible penalty and some hesitation to Hruska’s mind meant he was winning more, spending less and still getting his post-training treat.

It could have stopped there and remained a piece of unseen showboating. But Panenka realised his new technique was more than that. He had unearthed a legitimate 12-yard tactic.

Over the next couple of years, he tested it on larger and larger stages. First, in training, then in friendlies and finally, the month before Euro 1976, against local rivals Dukla Prague in a competitive fixture.

Each time it worked and his conviction grew.

“I made no secret of it,” Panenka says.

“Here [in Czechoslovakia] people were well aware of it.

“But in western countries, in top football countries nobody was interested in Czechoslovak football at all.

“Maybe they were kept up with some results, but they didn’t watch our games.”

So, there was no laminated cheat sheet or whispered instructions from a backroom analyst for Sepp Maier.

As the West German goalkeeper crouched on his goalline and fixed his eyes on Panenka, he had only his own instincts to go on.

Maier’s team-mate Uli Hoeness had blazed the previous spot-kick over the bar. It was the first miss of the shoot-out, after extra time finished with the teams still locked together at 2-2.

Instantly the stakes became sudden death and sky high. If Panenka scored, West Germany were beaten.

Panenka’s run-up was long and fast. He seemed intent, like Hoeness, on thumping his instep through the back of the ball.

Instead, with the most important kick of his life, he fell back on his trusted trick. A deft tickle sent the ball floating down the centre of the goal. Panenka’s arm was aloft in celebration before it hit the net. Maier, flummoxed and failing, scrambled back to his feet, but only in time to shoot a rueful look at Panenka wheeling away in celebration.

Football

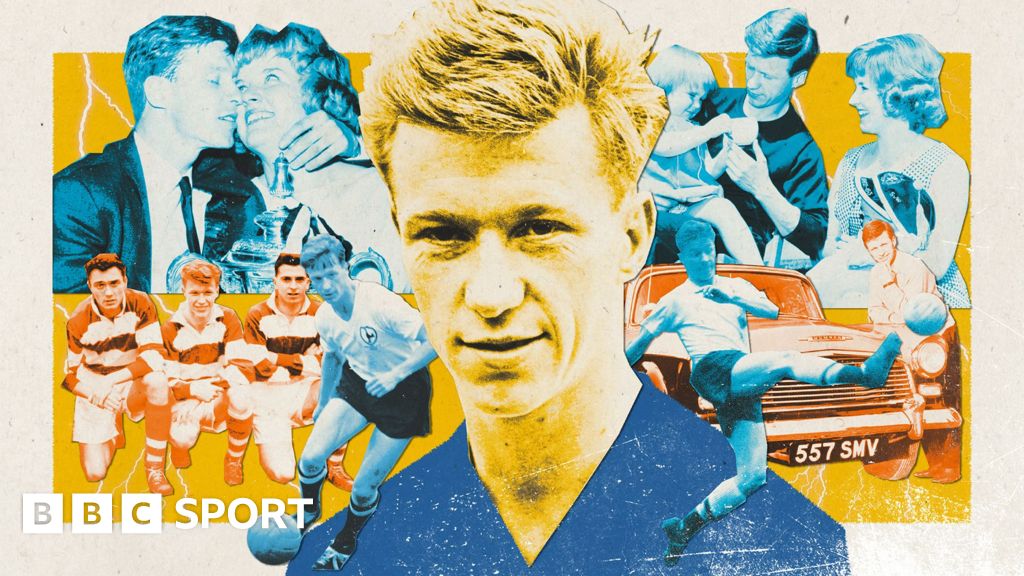

Tottenham’s John White and his son’s search for lost superstar

Too often, though, the character lacked depth: as thin as the page of the comic he seemed to spring from.

“He was this kind of Roy of the Rovers figure and as I got older I got frustrated and almost embarrassed by people having a better knowledge of my dad than I did,” Rob says.

“Part of the joy of having a father is finding our own identity – there is a little blueprint there and if we are lucky we follow the good bits and jettison the bad bits – but I didn’t have that.

“There is still a kid in me that wants to know the simple stuff: what he smelt like and sounded like, a bit more about him, rather than this persona. That is the eternal frustration.”

Rob channelled that frustration into a book – The Ghost of White Hart Lane – interviewing family members, former team-mates, friends and acquaintances, to try and discover the man behind the myth.

And gradually he found him.

Rob heard about the sadness and homesickness that would grip John each winter in London. He heard about the time he drove home dangerously drunk, clipping the White Hart Lane gates in his car. Most revealingly, an uncle told Rob about the child that John had fathered in Scotland and left behind before he travelled south, played for Spurs and met Sandra.

“Part of me has always been trying to live up to this person who was absolutely perfect, who was idolised not just by the family, but by hundreds of thousands of people,” says Rob.

“To find out he had defects and weaknesses, that he struggled with confidence, mental health and seasonal affective disorder, that he had made mistakes – if I had found all that out earlier, it would have made more sense to my life.

“If we know our parents are fallible, it really makes us understand that we can make mistakes. We don’t have to know all the answers.”

John’s absence shaped Rob as surely as his presence would have.

Rob is a still-life photographer – “I have always been looking for those details and clues” – and is also training as a counsellor.

Later this month, Rob will be in the audience at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium for the first performance of a play, called The Ghost of White Hart Lane, that he commissioned about his father’s life.

The staging is intended to share his father’s story to several generations of fans who remember neither John’s life or death.

“It is something I talk about with my own therapist,” he says. “Having seen life breathed into the story at the play’s read-throughs, it reinforced the reasons I wanted to get involved with the project.

“I think there is something of trying to bring my dad back to life.”

After two nights in Tottenham, the play will then transfer north, taking the opposite journey to the one John took in life, for a stint at the Edinburgh Festival., external

There are some things that remain lost. Rob is still searching for a recording of John’s voice. One of his match-worn Tottenham shirts remains elusive.

But over the decades, he has found much more: an understanding and an empathy for the father he never knew.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoYou’re a Hypocrite, And So Am I

-

Sport4 days ago

Sport4 days agoJoshua vs Dubois: Chris Eubank Jr says ‘AJ’ could beat Tyson Fury and any other heavyweight in the world

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoHow to unsnarl a tangle of threads, according to physics

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoOur millionaire neighbour blocks us from using public footpath & screams at us in street.. it’s like living in a WARZONE – WordupNews

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days ago‘Running of the bulls’ festival crowds move like charged particles

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoEthereum is a 'contrarian bet' into 2025, says Bitwise exec

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoWould-be reality TV contestants ‘not looking real’

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoDZ Bank partners with Boerse Stuttgart for crypto trading

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBitcoin miners steamrolled after electricity thefts, exchange ‘closure’ scam: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoDorsey’s ‘marketplace of algorithms’ could fix social media… so why hasn’t it?

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoLow users, sex predators kill Korean metaverses, 3AC sues Terra: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBitcoin bulls target $64K BTC price hurdle as US stocks eye new record

-

Travel16 hours ago

Where Retro Glamour Meets Modern Chic in Athens, Greece

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoWhy this is a golden age for life to thrive across the universe

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoIsrael strikes Lebanese targets as Hizbollah chief warns of ‘red lines’ crossed

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoHyperelastic gel is one of the stretchiest materials known to science

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoSunlight-trapping device can generate temperatures over 1000°C

-

Health & fitness5 days ago

Health & fitness5 days agoThe secret to a six pack – and how to keep your washboard abs in 2022

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoCardano founder to meet Argentina president Javier Milei

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoRedStone integrates first oracle price feeds on TON blockchain

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoSEC asks court for four months to produce documents for Coinbase

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoVitalik tells Ethereum L2s ‘Stage 1 or GTFO’ — Who makes the cut?

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBlockdaemon mulls 2026 IPO: Report

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoQuantum ‘supersolid’ matter stirred using magnets

-

Sport4 days ago

Sport4 days agoUFC Edmonton fight card revealed, including Brandon Moreno vs. Amir Albazi headliner

-

Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoiPhone 15 Pro Max Camera Review: Depth and Reach

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoMaxwell’s demon charges quantum batteries inside of a quantum computer

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoQuantum forces used to automatically assemble tiny device

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoBrian Tyree Henry on voicing young Megatron, his love for villain roles

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoITER: Is the world’s biggest fusion experiment dead after new delay to 2035?

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoLiquid crystals could improve quantum communication devices

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoPhysicists are grappling with their own reproducibility crisis

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoNuclear fusion experiment overcomes two key operating hurdles

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days ago$12.1M fraud suspect with ‘new face’ arrested, crypto scam boiler rooms busted: Asia Express

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoCertiK Ventures discloses $45M investment plan to boost Web3

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoVonMises bought 60 CryptoPunks in a month before the price spiked: NFT Collector

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days ago‘Silly’ to shade Ethereum, the ‘Microsoft of blockchains’ — Bitwise exec

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days ago‘No matter how bad it gets, there’s a lot going on with NFTs’: 24 Hours of Art, NFT Creator

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoCoinbase’s cbBTC surges to third-largest wrapped BTC token in just one week

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoChurch same-sex split affecting bishop appointments

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoTrump says he will meet with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi next week

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoLabour MP urges UK government to nationalise Grangemouth refinery

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoHow one theory ties together everything we know about the universe

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoTime travel sci-fi novel is a rip-roaringly good thought experiment

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoLaser helps turn an electron into a coil of mass and charge

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoHow to wrap your mind around the real multiverse

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days ago2 auditors miss $27M Penpie flaw, Pythia’s ‘claim rewards’ bug: Crypto-Sec

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoHelp! My parents are addicted to Pi Network crypto tapper

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoCrypto scammers orchestrate massive hack on X but barely made $8K

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoWhy we need to invoke philosophy to judge bizarre concepts in science

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoSEC sues ‘fake’ crypto exchanges in first action on pig butchering scams

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoElon Musk is worth 100K followers: Yat Siu, X Hall of Flame

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBitcoin price hits $62.6K as Fed 'crisis' move sparks US stocks warning

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoCZ and Binance face new lawsuit, RFK Jr suspends campaign, and more: Hodler’s Digest Aug. 18 – 24

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoTelegram bot Banana Gun’s users drained of over $1.9M

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoEthereum falls to new 42-month low vs. Bitcoin — Bottom or more pain ahead?

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoETH falls 6% amid Trump assassination attempt, looming rate cuts, ‘FUD’ wave

-

Business4 days ago

How Labour donor’s largesse tarnished government’s squeaky clean image

-

Politics4 days ago

‘Appalling’ rows over Sue Gray must stop, senior ministers say | Sue Gray

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBitcoin options markets reduce risk hedges — Are new range highs in sight?

-

Science & Environment17 hours ago

Science & Environment17 hours agoMeet the world's first female male model | 7.30

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoGuardian in talks to sell world’s oldest Sunday paper

-

Technology5 days ago

Technology5 days agoCan technology fix the ‘broken’ concert ticketing system?

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoDid the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

-

Politics6 days ago

Politics6 days agoTrump Media breached ARC Global share agreement, judge rules

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoA new kind of experiment at the Large Hadron Collider could unravel quantum reality

-

Fashion Models4 days ago

Fashion Models4 days agoMixte

-

Business6 days ago

Glasgow to host scaled-back Commonwealth Games in 2026

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoQuantum time travel: The experiment to ‘send a particle into the past’

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoReal-world asset tokenization is the crypto killer app — Polygon exec

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoDecentraland X account hacked, phishing scam targets MANA airdrop

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoBeat crypto airdrop bots, Illuvium’s new features coming, PGA Tour Rise: Web3 Gamer

-

CryptoCurrency4 days ago

CryptoCurrency4 days agoMemecoins not the ‘right move’ for celebs, but DApps might be — Skale Labs CMO

-

Business4 days ago

Thames Water seeks extension on debt terms to avoid renationalisation

-

Politics4 days ago

The Guardian view on 10 Downing Street: Labour risks losing the plot | Editorial

-

Politics4 days ago

Politics4 days agoI’m in control, says Keir Starmer after Sue Gray pay leaks

-

Business4 days ago

UK hospitals with potentially dangerous concrete to be redeveloped

-

Politics4 days ago

‘Hundreds’ of prisoners freed early in England and Wales not fitted with tags | Prisons and probation

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSean “Diddy” Combs denied bail again in federal sex trafficking case

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoWhy Is Everyone Excited About These Smart Insoles?

-

News16 hours ago

News16 hours agoFour dead & 18 injured in horror mass shooting with victims ‘caught in crossfire’ as cops hunt multiple gunmen

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPolice chief says Daniel Greenwood 'used rank to pursue junior officer'

-

Technology4 days ago

Technology4 days agoFivetran targets data security by adding Hybrid Deployment

-

Science & Environment5 days ago

Science & Environment5 days agoElon Musk’s SpaceX contracted to destroy retired space station

-

Politics6 days ago

Starmer ally Hollie Ridley appointed as Labour general secretary | Labour

-

Money5 days ago

Money5 days agoWhat estate agents get up to in your home – and how they’re being caught

-

Technology6 days ago

Technology6 days ago‘The dark web in your pocket’

-

News4 days ago

Freed Between the Lines: Banned Books Week

-

MMA4 days ago

MMA4 days agoUFC’s Cory Sandhagen says Deiveson Figueiredo turned down fight offer

-

MMA4 days ago

MMA4 days agoDiego Lopes declines Movsar Evloev’s request to step in at UFC 307

-

Football4 days ago

Football4 days agoSlot's midfield tweak key to Liverpool victory in Milan

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoHow to wrap your head around the most mind-bending theories of reality

-

Fashion Models4 days ago

Fashion Models4 days agoMiranda Kerr nude

-

Fashion Models4 days ago

Fashion Models4 days ago“Playmate of the Year” magazine covers of Playboy from 1971–1980

-

Fashion Models4 days ago

Fashion Models4 days agoAchtung Magazine

-

Fashion Models4 days ago

Fashion Models4 days agoNuméro Switzerland

-

Health & fitness5 days ago

Health & fitness5 days ago11 reasons why you should stop your fizzy drink habit in 2022

-

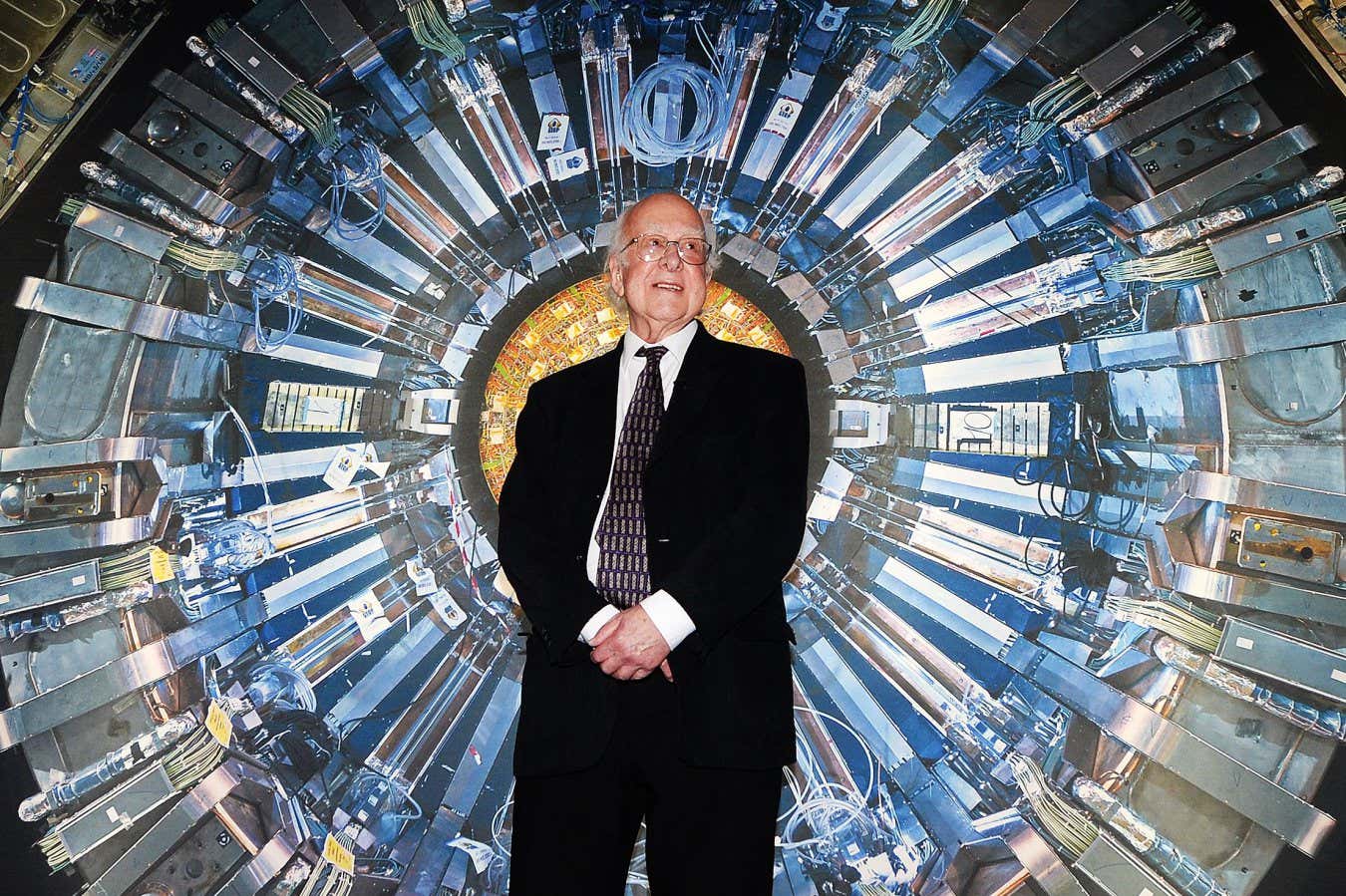

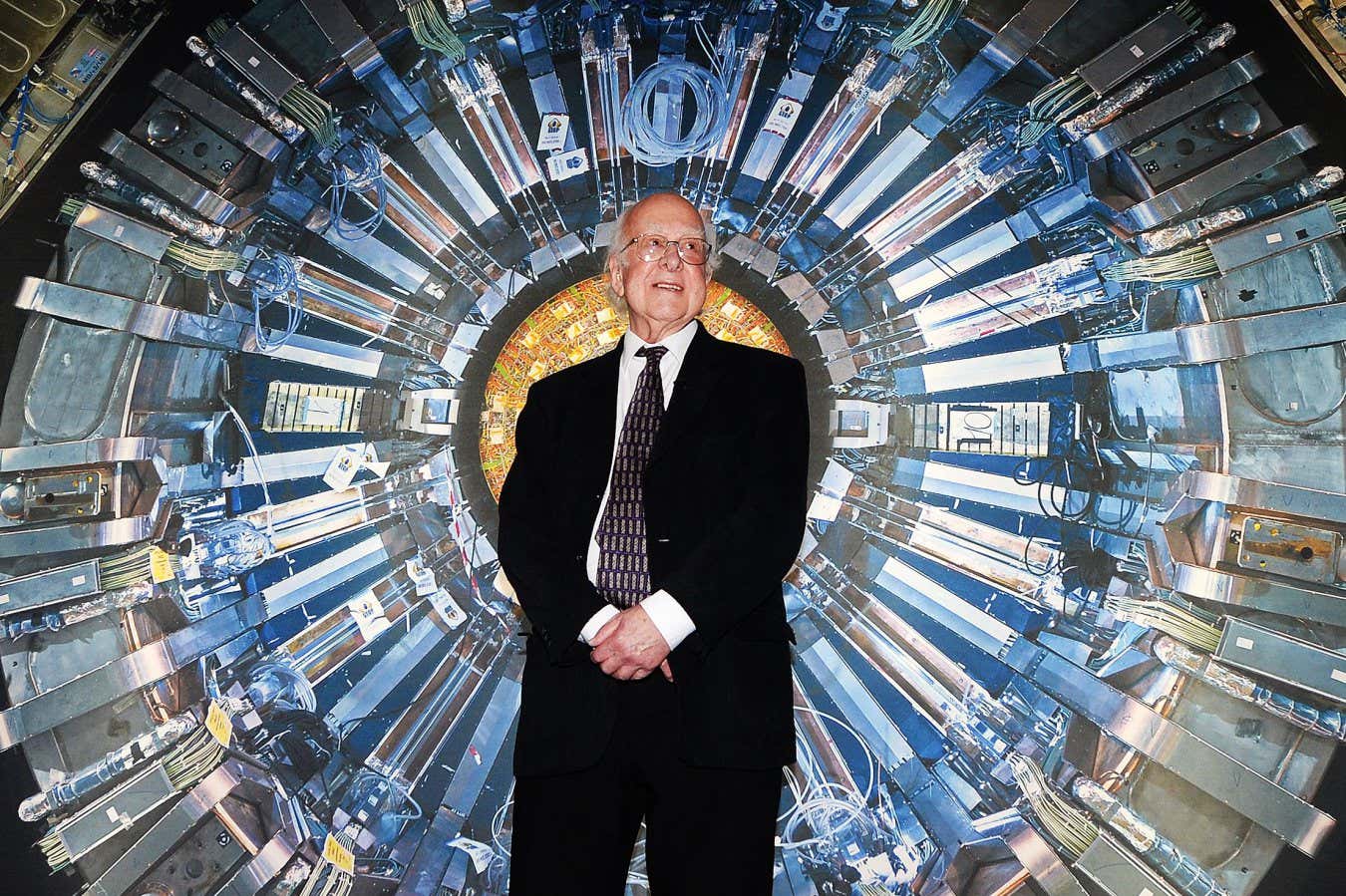

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoHow Peter Higgs revealed the forces that hold the universe together

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoOdd quantum property may let us chill things closer to absolute zero

-

Science & Environment4 days ago

Science & Environment4 days agoRethinking space and time could let us do away with dark matter

You must be logged in to post a comment Login