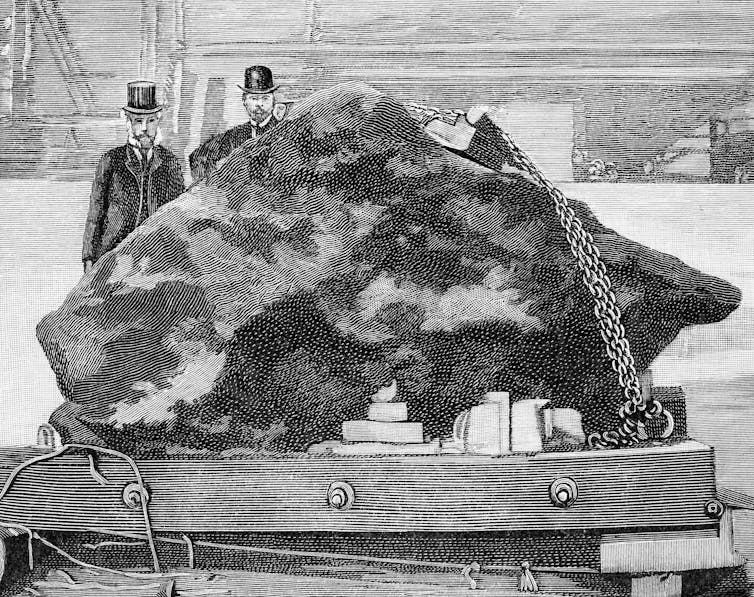

A 30-minute stroll across New York’s Central Park separates Trump Tower from the American Museum of Natural History. If the US president ever found himself inside the museum he could see the Cape York meteorite: a 58-tonne mass of iron taken from northwest Greenland and sold in 1897 by the explorer Robert Peary, with the help of local Inuit guides.

For centuries before Danish colonisation, the people of Greenland had used fragments of the meteorite to make tools and hunting equipment. Peary removed that resource from local control, ultimately selling the meteorite for an amount equivalent to just US$1.5 million today. It was a transaction as one-sided as anything the president may now be contemplating.

But Donald Trump is now eyeing a prize much larger than a meteorite. His advocacy of the US taking control of Greenland, possibly by force, signals a shift from dealmaking to dominance. The scientific cost would be severe. A unilateral US takeover threatens to disrupt the open scientific collaboration that is helping us understand the threat of global sea-level rise.

Greenland is sovereign in everything other than defence and foreign policy, but by being part of the Kingdom of Denmark, it is included within Nato. As with any nation, access to its land and coastal waters is tightly controlled through permits that specify where work may take place and what activities are allowed.

INTERFOTO / Alamy

Over many decades, Greenland has granted international scientists access to help unlock the environmental secrets preserved within its ice, rocks and seabed. US researchers have been among the main beneficiaries, drilling deep into the ice to explain the historic link between carbon dioxide and temperatures, or flying repeated Nasa missions to map the land beneath the ice sheet.

The whole world owes a huge debt of thanks to both Greenland and the US, very often in collaboration with other nations, for this scientific progress conducted openly and fairly. It is essential that such work continues.

The climate science at stake

Research shows that around 80% of Greenland is covered by a colossal ice sheet which, if fully melted, would raise sea level globally by about 7 metres (the height of a two storey house). That ice is melting at an accelerating rate as the world warms, releasing vast amounts of freshwater into the North Atlantic, potentially disrupting the ocean circulation that moderates the climate across the northern hemisphere.

Delpixel / shutterstock

The remaining 20% of Greenland is still roughly the size of Germany. Geological surveys have revealed a wealth of minerals, but economics dictates that these will most likely be used to power the green transition rather than prolong the fossil fuel era.

While coal deposits exist, they are currently too expensive to extract and sell, and no major oil fields have been discovered. Instead, the commercial focus is on “critical minerals”: high-value materials used in renewable technologies from wind turbines to electric car batteries. Greenland therefore holds both scientific knowledge and materials that can help guide us away from climate disaster.

Unilateral control could threaten climate science

Trump has shown little interest in climate action, however. Having already started to withdraw the US from the Paris climate agreement for a second time, he announced in January 2026 the country would also leave the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, the global scientific body that assesses the impacts of continued fossil-fuel burning. His rhetoric to date has been about acquiring Greenland for “security” purposes, with some indications of accessing its mineral wealth, but without mention of vital climate research.

Martin Nielsen / Alamy

Under the 1951 Greenland defence agreement with Denmark, the US already has a remote military base at Pituffik in northern Greenland, now focused on space activities. While both countries remain in Nato, the agreement already allows the US to expand its military presence if required. Seeking to guarantee US security in Greenland outside Nato would undermine the existing pact, while a unilateral takeover would risk scientists in the rest of the world losing access to one of the most important climate research sites.

Lessons from Antarctica and Svalbard

Greenland’s sovereign status and its governance is different to some other notable polar research locations. For example, Antarctica has, for more than 60 years, been governed through an international treaty ensuring the continent remains a place of peace and science, and protecting it from mining and other environmental damage.

Svalbard, on the other hand, has Norwegian sovereignty courtesy of the 1920 Svalbard treaty but operates a largely visa-free system that allows citizens of nearly 50 countries to live and work on the archipelago, as long as they abide by Norwegian law. Interestingly, Norway claims that scientific activities are not covered by the treaty, to almost universal disagreement among other parties. Russia has a permanent station at Barentsburg, Svalbard’s second-largest settlement, from which small levels of coal are mined.

Unlike Antarctica or Svalbard, Greenland has no treaty that explicitly protects access for international scientists. Its openness to research therefore depends not on international law, but on Greenland’s continued political stability and openness – all of which may be threatened by US control.

If it is minded to take a radical approach, Greenland could develop its own treaty-style approach with selected partner states through Nato, enabling security cooperation, mineral assessment and scientific research to be carried out collaboratively under Greenlandic regulations.

The future for Greenland should lie with Greenlanders and with Denmark. The future of climate science, and the transition to a safe prosperous future worldwide, relies on continued access to the island on terms set by the people that live there. The Cape York meteorite – taken from a site just 60 miles away from the US Pituffik Space Base – is a reminder of how easily that control can be lost.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.