News Beat

Superbug fears as new drug-resistant strains of typhoid emerge in Asia

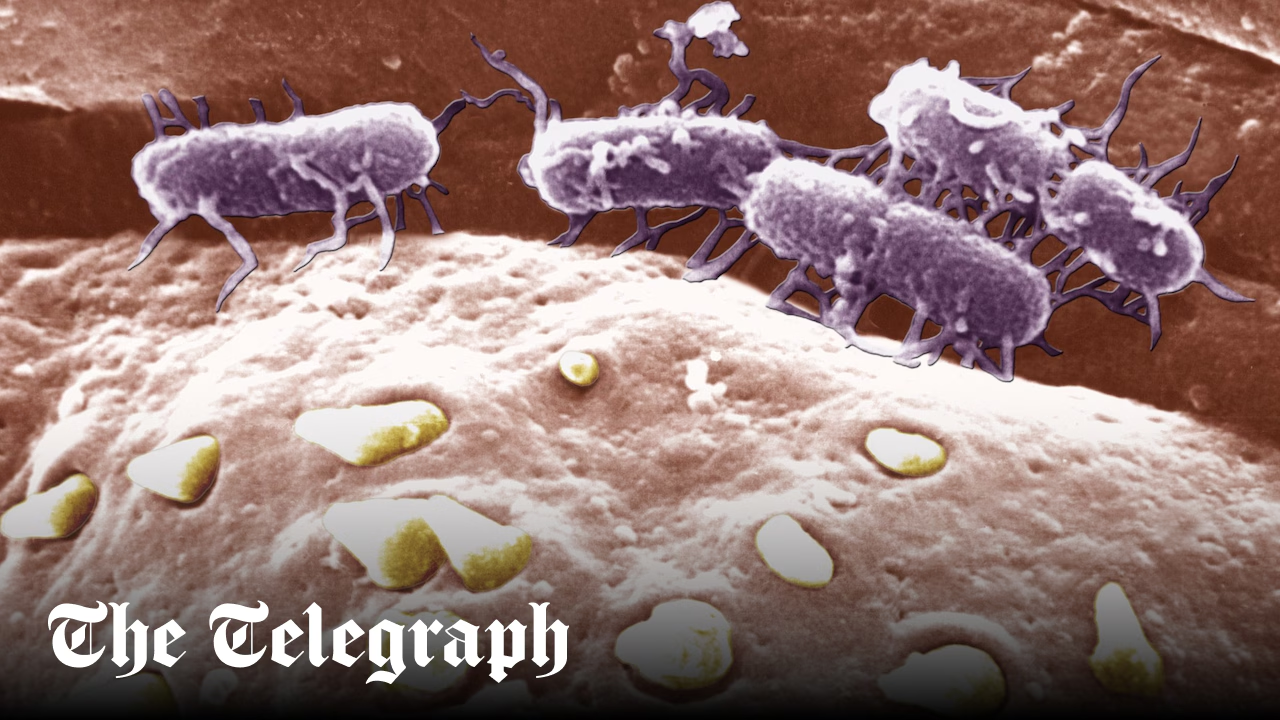

New strains of Typhoid that can resist the strongest available antibiotics have emerged in South Asia, raising concerns over the potential spread of drug-resistant infections.

A gene capable of breaking down carbapenems, a class of powerful antibiotics seen as a drug of last resort, was discovered among 32 samples collected from hospitals across western and southern India.

Testing showed that this gene, known as blaNDM-5, can move between different types of bacteria, raising fears that such resistance could spread quickly.

The discovery is the latest in a series of setbacks for efforts to contain the spread of typhoid.

Typhoid fever may sound like a relic of the past, but experts warn it is rapidly evolving into a 21st-century threat, one the world is unprepared for.

Recent outbreaks of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) typhoid across South Asia – strains resistant to most common antibiotics – highlight the danger.

Since 2016, more than 15,000 XDR typhoid cases have been reported in Pakistan, while strains resistant to the antibiotic azithromycin have also appeared in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, and beyond.

“We all hear that antimicrobial resistance is a problem, but typhoid really exemplifies it – how resistance seems to emerge relentlessly, moving from one class of antibiotics to the next,” Dr Malick Gibani, Clinical Lecturer in Infectious Diseases at Imperial College London, told The Telegraph.

“It’s not yet untreatable, but the treatments we do have are much more limited and significantly more challenging to deliver.”

‘A canary-in-the-coal-mine signal’

Typhoid is caused by the bacteria Salmonella Typhi, typically spread through contaminated food or water, and can cause high fever, stomach pain, and other serious complications if left untreated.

The first line of treatment is antibiotics, ranging from common drugs like amoxicillin and co-trimoxazole to stronger hospital-use antibiotics for resistant strains, like carbapenems.

If typhoid cannot be treated it can lead to severe complications and, in some cases, death.

But it is the discovery of typhoid that can resist even carbapenems due to the blaNDM-5 gene that has researchers concerned.

“Although the number of cases described is still relatively small, this feels very much like a canary-in-the-coal-mine signal,” said Dr Gibani.

“This was always going to happen and probably reflects the relentless evolution of AMR in typhoid. While these infections are not yet “untreatable”, they are clearly becoming much harder to manage.”

Experts say typhoid is often difficult to diagnose, and this uncertainty can lead to wider – and sometimes inappropriate – use of antibiotics, further driving up resistance.

They also fear that XDR typhoid could be even more widespread than current data indicates due to gaps in reporting in low-income countries, where the disease typically spreads.

“The danger is higher in places with uncontrolled antibiotic use, poor water quality, and limited healthcare infrastructure,” said Prof Calman A. MacLennan, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford.

“Mortality from typhoid today isn’t huge – less than one per cent of cases – but back in the pre-antibiotic era, it was 10 to 20 per cent. There were even wars where more people died from typhoid than from actual fighting, because it was so prevalent.”

According to Prof MacLennan, a relatively new vaccine – known as the Typhoid Conjugate Vaccine (TCV) – could offer hope for avoiding a resurgence of deadly typhoid.

“We know the typhoid conjugate vaccine is highly effective, and it works by harnessing the body’s own immune system rather than relying on an antibiotic binding to a specific bacterial target,” he said. “That kind of immune response is much harder for the pathogen to escape.”