Wallis Simpson is like the Battle of the Somme: so much has already been written, yet there still seems to be more to say. Do we really need another book about the twice-divorced woman for whom a king gave up his throne, the duchess who died demented, alone and unloved in Paris?

Well, as it happens, yes. The widespread contempt that Wallis attracted in her adopted country was largely based on the putative “China Dossier”, a document which, if it ever existed at all, is now lost.

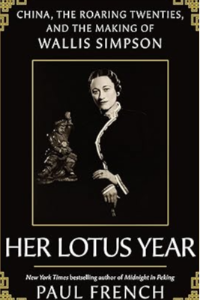

In Her Lotus Year, Shanghai-based historian Paul French writes that it was probably the “lascivious fabrication of someone in Special Branch or MI5”, disseminated in the 1930s to discredit her and put a stop to her burgeoning affair with the Prince of Wales. Detailed and disdainful, the dossier suggested she was promiscuous and predatory; that she had an affair with Mussolini’s fascist son-in-law; that she attracted her myriad lovers by using recondite sexual tricks learned in the brothels of Shanghai. And much more.

French is a fine and compelling writer, acclaimed author of a dozen books about old China. His painstaking, forensic research proves beyond reasonable doubt that although there was some truth in these sly and scandalous tales, none of them could have involved Wallis: the dates simply do not add up. She was certainly no angel, but nor was she the monster created by an establishment whispering campaign.

The story begins in September 1924, when Bessie Wallis Winfield Spencer sailed into Hong Kong harbour where her estranged husband Earl Winfield Spencer Jnr, known as Win, was awaiting her. Seconded to the navy from the air force, Win apparently thought he might save his marriage, though he soon relapsed into morose drunkenness. When he was posted to Canton, Wallis followed him, maybe for one last try. There, however, he became violent, and she realised that divorce was inevitable. Hoping, in vain, to obtain a decree from the American court, she moved on to Shanghai, and then to Peking.

French suggests an interesting reason for her travels. China was riven by fierce battles between rival warlords, backed by various foreign powers. Some names, like Chiang Kai-shek or Sun Yat-sen, are familiar: others are known by nicknames. Chang Tsung-chan was familiarly known as the Three-Don’t-Knows General, since he couldn’t keep count of how much money, how many soldiers and how many concubines he had.

But it was no joke to travel through this bandit country. All rail journeys were cancelled, yet Wallis got through, on English or American ships, and was generally met on arrival, usually by influential men. French thinks she may well have been acting as a courier, passing information between European and American diplomatic legations, and he makes a good case for it. In fact, he presents a pretty good case for Simpson having been not only competent but genuinely admirable, even — almost — likeable.

There is no doubt that she fell on her feet. She often stayed in beautiful hotels and seemed always to meet helpful, generous people, especially in Peking. Her time there forms the best part of the whole story. Always adventurous, she rode at dawn along the Tartar Wall, picnicked in splendour in old Buddhist temples in the Western hills and discovered all the elements of the distinctive style that she was to make her own. She made money from playing poker and bridge and spent it buying cloisonné, silks, screens and jewellery.

It was the kind of thrilling, magical, romantic place you could now only visit in your dreams, as poor Wallis probably did in the punishing years of her final marriage, which offered her, after so much turmoil, something less than a fairytale ending. She once was heard to remark: “You have no idea how hard it is to live out a great romance”.

Her Lotus Year: China, the Roaring Twenties and the Making of Wallis Simpson by Paul French, Elliott & Thompson £25, 304 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen

You must be logged in to post a comment Login