Business

Carbon Capture and Hydrogen: The Last Pieces to Net Zero

Solar farms, wind turbines, and electric vehicles are crucial to slash carbon emission, but they can’t carry Thailand all the way to net zero.

The real game-changers might be two lesser-known technologies: Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage (CCUS)and hydrogen.

Together, CCUS and hydrogen are being hailed as the “last-mile” solutions to slash emissions that can’t be avoided, especially in heavy industries like steel, cement, and petrochemicals. These sectors are the backbone of the economy, but also among the hardest to clean up.

These two technologies of the future are the missing pieces to help the world—and Thailand—reach its carbon neutrality and net-zero targets.

In short, to save the planet and humanity.

The catch? They’re still very costly and stuck in a tangle of policies and legal gaps. But if Thailand wants a truly low-carbon future, these two technologies might just be the keys to get there.

How CCUS works

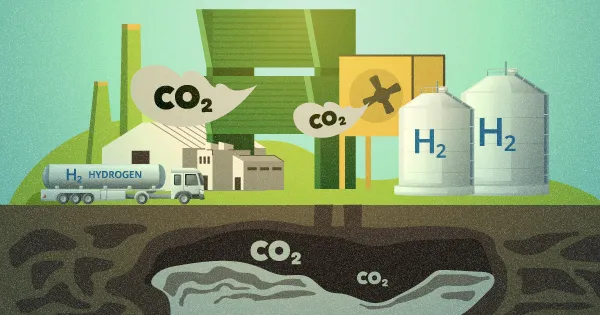

CCUS works by capturing carbon dioxide (CO₂) before it escapes into the air—usually from factory chimneys or other emission sources. The captured gas is then stored deep underground in layers of rock or put to use in other ways, such as being processed into new materials or reused in the energy and petrochemical industries.

Around the world, this technology captures about 400 million tonnes of carbon each year, still a drop in the ocean compared to total emissions.

Some countries are moving fast. In the United States, the Gulf Coast industrial cluster now traps more than 20 million tonnes of CO₂ a year, with plans to scale up sevenfold to 140 million tonnes.

This progress didn’t happen by accident. It’s driven by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which gives companies up to 85 US dollars in tax credit for every tonne of carbon they capture. Capturing one tonne of carbon can cost anywhere between 15 and 120 dollars depending on the emission source.

Without tax incentives from the government, CCUS would be too costly and economically unviable.

Thailand also has potential. A study by the Global CCS Institute suggests the Gulf of Thailand could store more than 8.4 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. This is enough to keep emissions safely locked away for decades.

But CCUS won’t take off in Thailand unless the government get four things right.

First, it needs to set clear national CCUS targets that fit with the country’s net-zero goals. Second, there should be one government body in charge, with proper laws and rules covering every step of the value chain.

Third, investors need a reason to get on board. They need financial support and incentives that make the effort worth their while. And most importantly, Thailand needs a fair carbon price, so the market itself starts pushing the change.

Green Hydrogen

While CCUS tackles emissions that can’t be avoided, hydrogen offers a path to cleaner fuel. When burned or used in fuel cells, hydrogen releases no carbon at all. Hydrogen, particularly green hydrogen made with renewable energy, can even store power for weeks to solve one of the biggest problems of solar and wind energy: their instability.

Many developed countries are racing ahead with hydrogen technology. Germany is building a 1,200-kilometre hydrogen pipeline network to connect industries across the country by 2030.

Japan has had a hydrogen strategy since 2017 and recently passed new laws—the GX Promotion Act (2023) and Hydrogen Society Promotion Act (2024)—to speed up real-world use, including testing ships that carry liquid hydrogen.

Meanwhile, Australia aims to become a major hydrogen exporter, starting with hydrogen made from coal and CCUS, and moving to full-scale green hydrogen by 2030.

Thailand has started to move too. There are plans to test green hydrogen mixed with natural gas to generate electricity, but that may not be efficient in the long run. Making hydrogen from clean electricity only to turn it back into power wastes energy at several stages. A better use would be in heavy transport as fuel for trucks, buses, and cargo ships that need steady, high power.

There are several pilot projects in the heavy transport sector. For example, the state energy firm PTT aims to produce green hydrogen and build filling stations to serve 30-50 hydrogen-powered trucks. A Thai–Japanese partnership is also testing 20 trucks that can run more than 600 kilometres a day on hydrogen fuel cells.

But cost remains a major roadblock. Green hydrogen now costs 280 to 340 baht per kilogramme. To compete with diesel, it must drop to around 200. Domestic demand is still weak too, as Thailand lacks both infrastructure and clear policy direction.

Thailand is taking its first steps into the hydrogen era. The progress is small but promising. Still, without faster action, the country risks becoming just an importer of hydrogen rather than a developer that can add value and create jobs at home.

To make hydrogen part of the real economy, Thailand needs to move on several fronts.

Green hydrogen should first be used in heavy transport—trucks, buses, and ships that need powerful, continuous energy. The government also needs to set clear safety standards and update the rules to officially allow hydrogen as a fuel.

Costs have to come down too, so green hydrogen can compete with diesel. And to make it practical, Thailand must expand its refuelling network, attract private investment, and fund more research and development.

Both CCUS and hydrogen hold enormous promise. But that promise will remain out of reach without clear long-term goals, coherent policies, strong laws, and the right financial incentives.

The sooner Thailand invests in these technologies of the future, the greater its chance of shaping, not just surviving, the world’s next energy revolution.

(Note: This article was part of the Energy Transition Policy Leadership Programme, supported by the Energy Regulatory Commission’s Power Development Fund, 2024.)

Areeporn Asawinpongphan, Ph.D. is a Research Fellow , Korn Amnauypanit and Annop Jaewisorn are Reseacher at the Thailand Development and Research Institute (TDRI). Policy analyses from the TDRI appear in the Bangkok Post on alternate Wednesdays.