Now would be a good time for investors to curb their enthusiasm, just a little. This year has begun with the bulls largely in control. Already, US stocks have risen about 4 per cent, making this one of the stronger opening months to any year in the past decade.

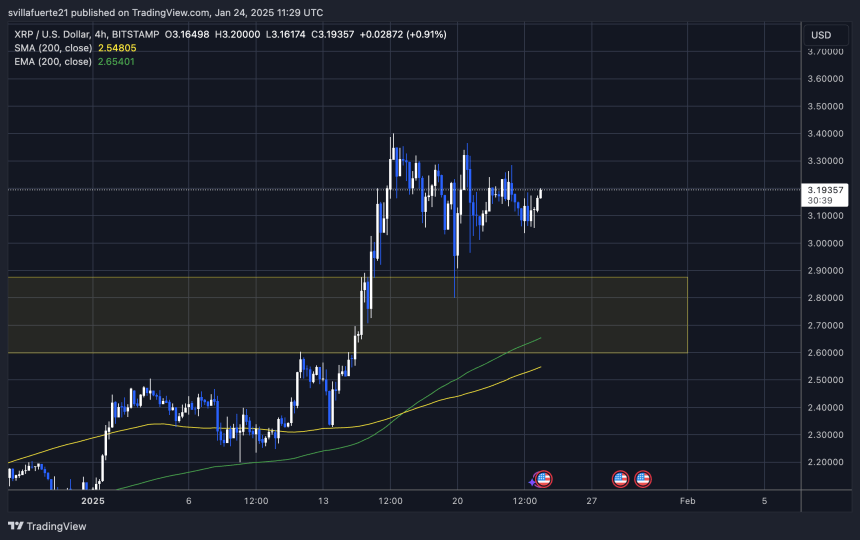

The re-inauguration of Donald Trump as US president has ushered in a new period of “animal spirits” among business executives, as veteran investor Stan Druckenmiller put it this week. Chief executives are “somewhere between relieved and giddy” at the election result, he told CNBC. Meanwhile, US banks are in “go-mode”, a senior JPMorgan executive told the Davos crowd, while crypto is on the cusp of entering the “banana zone”, according to its boosters. (Nope, me neither. Apparently that’s good, though, indicating prices are about to surge.)

HSBC is sticking with the good vibes. Its multi-asset team this week outlined an “extremely positive” backdrop for risky assets in the first half of this year — a scenario it described as “Goldilocks on steroids”, quite the mental image.

At the risk of spoiling all the fun, some market watchers — including some of the optimists — are getting a little nervous. The first big reason is the global government bond market, which has got off to a wobbly start to the year. This is not entirely a bad thing — it reflects a continuation of the US economic growth miracle. But it also reflects an expectation that inflation will continue to stick around and that the Federal Reserve will therefore struggle to keep reducing interest rates — no matter how much Trump would like it to. On the margins, it also suggests asset managers demand a somewhat higher rate of return for feeding government coffers.

Whatever your preferred narrative here, the point is that bond investors have been wrongfooted (again) and that the resulting drop in prices has pushed yields up (again). The most important benchmark of them all — the US 10-year yield — is sitting well above 4.5 per cent. That marks a recovery in prices since mid-January but is still high enough to undermine the case for loading up on stocks.

As my colleagues reported this week, US stocks have now reached their most expensive point relative to bonds in a generation. It is becoming ever harder to justify venturing further into stocks when their expected profits compared with earnings have sunk so far below the risk-free rate.

Peter Oppenheimer, chief global equity strategist at Goldman Sachs, noted at an event at the bank’s swanky London office this week that stocks had largely shrugged off this competition from bonds so far — in large part because optimism around growth is so strong. But that leaves equities now “vulnerable to further rises in yields”.

It is mildly silly but nonetheless true that much here depends on round numbers, which act as useful psychological signposts to investors. The big test would be if US yields hit 5 per cent. At that point, one of two things would happen: the bond haters would capitulate and snap up some bargains to pull the yield back down again, or selling would intensify and every asset class would feel the pain. My strong hunch is the former.

We are not at that point yet, but as Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, put it this week, “we’re still at a critical level”.

“We’re really getting close to the zip code where slightly slower growth and slightly higher rates become a deadly combination for the markets,” she said. As a result, she is sceptical that equities in general, and highly concentrated, highly tech-dependent US stock markets in particular, can continue the spectacular run of the past two years. Shalett is anticipating gains in US stocks of between 5 and 10 per cent this year. That is not bad, by any stretch, but it would not be a repeat of the 20 per cent-plus performance in each of the past two years.

Another factor tapping on the alarm bells is the level of optimism itself, especially among retail investors. The American Association of Individual Investors reported that sentiment had “skyrocketed” in its latest monthly survey. Expectations that stock prices will rise over the next six months jumped by some 18 percentage points to January, the AAII said.

Even optimistic wealth managers, who advise a lot of these investors, are having a hard time holding them back. Ross Mayfield, an investment strategist for Baird Private Wealth Management, told me this week that he believes in the bull market, albeit with half an eye on bond yields, which have moved “up and to the right with no obvious reason”. But he sees anecdotal signs that the American exceptionalism theme is becoming overly entrenched among his clients. “I’m starting to get questions about whether you need to diversify at all,” he said.

None of this is a reason to run to the hills and shelter in the safest assets you can find. But the air is getting somewhat thin at these heights and the potential for slip-ups from the new US presidential administration is strong. Glassy-eyed optimism rarely ends well, no matter how muscly Goldilocks becomes.

katie.martin@ft.com

You must be logged in to post a comment Login