Days before last year’s presidential election in Argentina, supermarket worker Emir Gullo was excited about the idea of a madman as president.

“He’s crazy,” Gullo said admiringly at a rally for libertarian economist and then-candidate Javier Milei on the outskirts of Buenos Aires in late 2023, noting his eccentric image, unconventional ideas and lack of government experience. “We’re tired of the same old politicians who say they’ll fix things and never do. We have faith that a madman can change Argentina.”

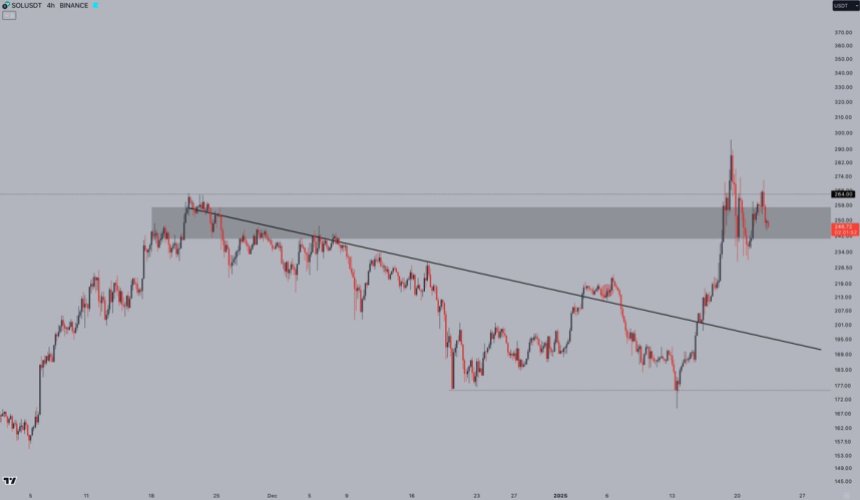

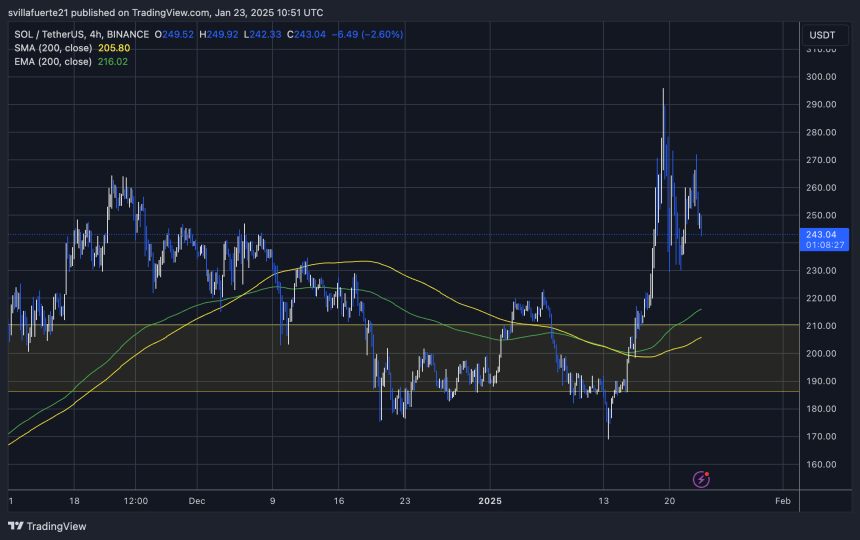

A year into his tenure, Milei appears to be proving Gullo right. Having taken over an economy on the brink of hyperinflation, Milei slashed the monthly inflation rate from 26 per cent last December to 2.7 per cent in October. The chronically depreciating peso — which Milei compared to “excrement” last year — has strengthened significantly against the black market dollar over the past six months. Since his election, Argentina’s long-distressed sovereign bond prices have roughly tripled.

Political analysts initially predicted the former TV commentator would struggle to get much done. His ideas were too radical, his personality too irascible, his three-year-old La Libertad Avanza coalition too inexperienced.

Yet Milei has used executive powers to get around his lack of a majority in Congress, enacting hundreds of deregulation measures and putting the opposition on the back foot. He has also slashed public spending to deliver a primary fiscal surplus every month this year — after more than a decade of uninterrupted deficits — without setting off widespread protests threatened by his opponents.

Milei has made powerful friends in US president-elect Donald Trump and Tesla chief executive Elon Musk, and his small-state message has made him the darling of hedge fund managers and private equity executives alike.

More importantly — and perhaps surprisingly — polls consistently show he has retained the support of half of Argentina’s population. “The economic and social cataclysm they predicted never came,” Milei told the Financial Times in October. “I have a 50 per cent approval rating after carrying out the biggest austerity programme in our history. It’s a miracle, isn’t it?”

Milei has reason to boast: he has stabilised a notoriously turbulent economy that had fallen into its worst crisis in two decades after the left-leaning Peronist government printed billions of dollars’ worth of local currency to fund spending.

But Argentina’s situation is still critical. While the economy appears to be emerging from a recession that began last year, it is expected to finish this year 3 per cent smaller than in 2023, according to JPMorgan. The bank’s growth forecast of 5.2 per cent in 2025 would only return Argentina’s per capita GDP to where it was in 2021, as it emerged from the pandemic.

With industries and wages depressed, Argentines have yet to recover from a steep drop in living standards that began roughly a decade ago, and accelerated in the early months of Milei’s presidency. The share of the population living in poverty climbed 11 percentage points in the first half of 2024 to 53 per cent, according to the national statistics agency.

But people who voted for Milei say they are satisfied. “It’s been a bad year for me personally, I’ve used up my savings to survive, but I have faith,” says Virgínia, 63, a retired teacher in the capital’s Abasto neighbourhood. “I’ve always said that this country needed to rip everything up and start from scratch, and he’s really doing it.”

Facundo Gómez Minujín, Argentina country head for JPMorgan, compares the country when Milei took over to a business going through bankruptcy “with a lot of assets, but in financial distress”.

“The company is getting out of Chapter 11 after less than a year,” he says. “Things couldn’t be better from where I stand.”

Milei has prioritised tackling Argentina’s inflation rate above all else. His main strategy has been “taking a chainsaw to the state”, as his catchphrase goes, cutting spending from 44 per cent to 32 per cent of GDP. The largest savings came from cuts to pensions, public works, public sector salaries, energy and transport subsidies, and social programmes.

Meanwhile, economy minister Luis Caputo, a former Wall Street trader, executed a complex financial strategy to turn off what he described as “money printing taps” that had been gushing excess pesos from the central bank into the economy.

After a big initial devaluation last December, Milei and Caputo have kept the peso’s government-controlled official exchange rate steady, devaluing at just 2 per cent a month. They injected some $15bn into the financial system via a generous tax amnesty that enticed Argentines to deposit dollars they had hidden under mattresses or in overseas banks. This has reduced demand for black market dollars and eased pressure on the exchange rate.

For many, the results feel like stability. “Things are going better than I expected,” says Jorge, a butcher in Barrio Padre Múgica, a working-class Buenos Aires neighbourhood, who cast a blank vote in last year’s election. But his sales remain well below early 2023 levels, he adds. “They stabilised the economy, but now it’s stuck. They need to get it moving again.”

The domestic-facing industries that employ most Argentines — retail, manufacturing and construction — have rebounded only slightly from deep contractions earlier this year. Unemployment ticked up 1.4 points year on year in the second quarter of 2024 to 7.6 per cent. Manufacturing businesses warn they may continue shedding labour as Milei opens up a long-protected economy to imported goods.

Pablo Yeramian, director of the textile business Norfabril, based in the provinces of San Luis and Corrientes, has cut 15 per cent of his roughly 275 staff this year and may need to lay off more. “We’re not on a level playing field with foreign companies,” he says, citing high taxes and a rigid labour market.

Inflation has battered Argentines’ take-home pay. In the first four months of Milei’s presidency, the average wage in the formal private sector fell 11 per cent in real terms from November 2023, to its lowest level in 20 years. It has since rebounded to just 2 per cent below last November. But salaries in the public sector, which employs a fifth of workers, remain 17.5 per cent down.

Alfredo Serrano Mancilla, head of the leftwing think-tank Centro Estratégico Latinoamericano de Geopolítica, compares the rebound in activity to a dead cat bounce. “This is not a structural recovery, [because] Milei hasn’t solved the structural problems in Argentina’s microeconomy,” he says. “This is a model with a very short expiration date.”

But Dante Sica, a former production minister for a centre-right government who runs the ABECEB real economy consultancy, claims that the labour market has begun a painful but necessary shift “after creating no new formal private sector jobs in over a decade”.

Argentina’s agriculture, mining and energy exports have soared this year thanks to the end of a severe drought and the culmination of years of investment in projects such as Vaca Muerta, one of the world’s biggest shale deposits. Sica says those sectors and tech services “are clearly going to be motors of growth, and they will lift up the rest”, although they currently make up only 14 per cent of jobs.

Pierpaolo Barbieri, chief executive of fintech company Ualá, says he sees “potential for a blockbuster year of growth in 2025 if the government can keep delivering macro stability”.

“This economy has been in some kind of crisis since we launched six years ago,” he adds. “If we can have a non-crisis year, it would be a big deal.”

When Milei took power, he had the smallest congressional force of any president in modern Argentine history, with less than 15 per cent of seats in both houses.

Yet Milei has managed to enact most of his priorities. He did so by pushing executive power to its limits with emergency decrees and vetoes, leveraging his direct connection with voters via a flurry of posts on social media to pressure lawmakers, and negotiating fiercely with Argentina’s 23 provincial governors after slashing their funding.

“Whether you like it or not, he has been very skilled in bending Argentina’s political system to his will,” says one Argentine diplomat.

The wild-haired libertarian remains an unconventional president. His public appearances swing abruptly from leather jacket-clad live performances of rock songs to opaque lectures on niche economic theory. Chants against the media and other “enemies of good Argentines” are a fixture at his rallies.

The most powerful decision makers in his government are his sister, Karina, who is his chief of staff, and the social media guru Santiago Caputo, a contractor who holds no formal office yet possesses broad influence over policy and staffing. Milei is in a public spat with his ambitious vice-president, Victoria Villarruel, about her loyalty and last month said she has “no influence whatsoever” on decision making. More than 30 high-level officials have already been pushed out, including four ministers.

On key issues, however, the president has proved pragmatic. He shelved his election pledge to dollarise the economy and “burn down” the central bank. He formed an early alliance with former conservative president Mauricio Macri, appointing figures from Macri’s 2015-19 government to lead three of his eight ministries.

He has also abandoned rhetoric referring to the government of China, Argentina’s second-largest trading partner after Brazil and a crucial lender, as “murderous communists”. At the G20 summit in November, President Xi Jinping congratulated Milei on his “commitment to economic recovery”.

Meanwhile, the opposition is in disarray. Centrist coalitions have squabbled over which Milei policies to support, while the Peronist movement has failed to agree on a message challenging austerity. Its leader is Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a highly divisive former president convicted on corruption charges.

Speaking to supporters last month, Fernández argued that Milei “wants to reduce us again to a simple colony that exploits raw materials . . . This is not the country we want.”

Peronist governments, led by Fernández and her late husband, Néstor Kirchner, nearly doubled the size of Argentina’s public sector from 2003 to 2023, spending heavily on welfare programmes and running deficits to help pay for them. Poverty rates fell sharply. But as inflation increased in the mid-2010s, wages began to fall.

Argentina’s powerful labour unions have held a few strikes since Milei took over, but they have been relatively short. Some leaders admit they have struggled to draw the mass participation they expected.

“Society holds us partly responsible for the crisis, alongside politicians,” admits Gerardo Martínez, the leader of Argentina’s construction workers’ union. “For now they feel they need to trust in something new to solve Argentina’s structural problems.”

Buoyed by his economic success, Milei has increasingly pursued a “cultural battle” against leftwing ideology, particularly on the global stage where he has pitched himself as a leader for the hard right. He has made 17 trips abroad — almost half to the US, one to Israel, and four including meetings with Musk — and delivered dozens of conference speeches on the dangers of the “woke mind virus”.

A week after the US election, Milei attended a Mar-a-Lago gala, becoming the first world leader to meet Trump since his victory. When Trump tipped Musk to co-lead an advisory Department of Government Efficiency to slash government bureaucracy, Milei declared: “We are exporting our chainsaw deregulation model around the world.”

Milei could use strong allies in the White House. While Argentina has relatively little importance for US trade and foreign policy, the US is the largest shareholder at the IMF, from whom Milei is hoping to borrow up to $10bn on top of the $44bn Argentina already owes.

Diplomats in Argentina fret privately that Trump’s return could unleash a more ideological, less pragmatic Milei. His foreign ministry has signalled Argentina may follow Trump if he goes through with a pledge to leave the Paris Agreement on climate change. Experts say exiting could cost Argentina international funding.

“I think he’s enjoying playing the maverick, but so far he has ended up being pragmatic when it counts,” says one foreign official in Buenos Aires. “Is there a risk he gets carried away now that Trump is back? I hope not.”

Milei has surpassed expectations. Now he is raising them. “The recession has ended, from now on, everything is growth,” he told a business event in November. “From now on, everything will be good news.”

It is a risky strategy, says Marcelo Garcia, Americas director at consultancy Horizon Engage. “This year Argentines are saying, ‘I suffered, but I was rewarded: inflation came down,’” he observes. “But if the economy doesn’t recover dramatically . . . if this turns out to be the new normal for a while, will they eventually say, ‘I have suffered enough’?”

Concerns about jobs, poverty and salaries are “threats on the horizon”, says Shila Vilker, director of the Trespuntozero polling organisation. “But our numbers give Milei a lot to celebrate. You can’t overestimate how much Argentines wanted stability, and they feel he delivered it.”

For that stability to give way to sustainable growth, however, Milei must overcome several huge challenges, chief among them the lifting of Argentina’s strict capital and currency controls, which set the official exchange rate and prevent companies and individuals from moving money freely out of Argentina.

Lifting the controls is “an absolutely necessary condition to see a real spike in foreign investment”, says Kezia McKeague, a director at strategy firm McLarty Associates.

Yet Milei argues that he cannot risk floating the peso without a large supply of hard currency in the central bank to calm markets and prevent a run, which would trigger inflation. He inherited virtually empty central bank reserves and has struggled to rebuild them as he spends dollars keeping the peso stable.

Milei had hoped to solve the dilemma with that IMF deal, but the fund has been slow to increase its exposure to what is already by far its biggest debtor. Finance minister Caputo said last month that exchange controls would “without a doubt” be lifted next year, though that could mean waiting until after midterm elections in late 2025.

Investors are bullish nonetheless. Argentina’s country risk — the premium over US Treasuries that investors demand to hold its bonds — has dropped from more than 2,000 basis points to about 750 since Milei took office, on growing expectations that Argentina will meet its 2025 debt repayments.

But Eduardo Levy Yeyati, an economist who advised the centre-right Macri government, cautions that Argentina has had “many successful stabilisation plans” that later failed.

Milei would need to succeed on growth, reserves and inflation at the same time, before “we can start thinking about a country that may no longer be stuck in that loop”, he adds.

“In Argentina, it’s always premature to call the end of the crisis.”

Data visualisation by Keith Fray

You must be logged in to post a comment Login