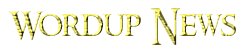

Donald Trump says he was “saved by God to make America great again”. Yet the best rebuttal to his presidency so far has come from a priest — the Episcopal bishop of Washington.

The Rt Rev Mariann Budde’s sermon on Tuesday went where business leaders and even Democratic politicians have struggled to go. While Trump sat a few metres away in the congregation, she asked him to show mercy to gay, lesbian and transgender people and to immigrants who are “scared” by his policies.

“Our God teaches us that we are to be merciful to the stranger, for we were all once strangers in this land,” Budde said at the service. It wasn’t a fleeting rebuke to Trumpism; it was an eloquent 15-minute argument for a different politics.

Trump sat there, fidgeting then fuming in the National Cathedral. His vice-president JD Vance, a Catholic, dissented by whispering to his wife. Perhaps they weren’t expecting it. Because at the inauguration the previous day, they were given a very different religious reception.

Preachers described Trump’s return as a “miracle”. One pastor, Lorenzo Sewell, invoked Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech in his honour.

In 2023, the charismatic Sewell was locked out of his Detroit church because its constitution had been changed and he was able to disenfranchise rank-and-file members. Shortly after the inauguration, he launched a crypto token, telling X users: “I need you to go buy the official Lorenzo Sewell coin.” The currency’s price then quickly plunged more than 90 per cent.

Who represents the Christian view of Trump? Is it Sewell with his pro-Trump, pro-prosperity talk of self-reliance, or the liberal Budde, who wants to speak for the marginalised? And, if Christianity can encompass both outcomes, is it much use for understanding and confronting Trump?

Budde backed up her address with references in the Bible. She is in line with Pope Francis, who has criticised Trump’s planned mass deportations of immigrants as a “disgrace”.

In contrast, pro-Trump spirituality often seems to rely on taking words from their context. Sewell stripped King’s dream of its intended meaning. (As for Sewell’s oratory, let me just say: the phrase “Free at last” is not meant to sum up what the audience feels when you stop talking.)

Or take the conflation of Christianity and growth. Another conservative speaker at the inauguration, Rabbi Ari Berman, suggested that George Washington had called faith and morality indispensable to “American prosperity”. In fact, Washington said they were essential to “political prosperity”. The context, back in 1796, was an appeal for national unity, and a warning not to trust in “the absolute power of an individual”. Trump would have fidgeted through that speech, too.

But pro-Trump pastors are accepted as a valid part of the church like any other. And the pews are with the president, too. According to Michael Emerson, a researcher on religion, practising Christians are now heavily Republican, because liberal Protestants and Catholics have disproportionately stopped going to church.

Last year Trump won around 60 per cent of the Christian vote, and more than 80 per cent of white evangelicals. He paid hush money to a porn star, has pledged to veto any federal abortion ban and he did not seem to place his hand on the Bible at the inauguration. But some white evangelicals see him as a useful vessel, someone who will allow them to steer the conversation.

Ironically, having invoked God multiple times in his inaugural address, Trump complained that Budde’s sermon had mixed politics and religion. One thing Sewell and Budde agree on is that you can’t keep politics out of Christianity. If the church decides simply to bless whoever is in power, it ends up compromised.

The question becomes: is religion downstream from politics? Will Trump’s supporters simply retrofit their faith on to their preferred politics, and his opponents do the opposite? The answer is probably: mostly, but not always. Surely there’s no point in listening to a preacher if you don’t think they’ll ever change your mind.

“When we know what is true, it’s incumbent upon us to speak the truth even when, especially when, it costs us,” Budde said. Her achievement shouldn’t be measured in how many people attend her next service. It should be measured in how many other people feel a duty to speak out against what they know is wrong.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login