THIS ARTICLE IS republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Severance, which imagines a world where a person’s work and personal lives are surgically separated, returns Friday for its long-awaited second season. While the concept of this gripping piece of science fiction is far-fetched, it touches on a question neuroscience has been trying to answer for decades: Can a person’s mind really be split in two?

Remarkably, “split-brain” patients have existed since the 1940s. To control epilepsy symptoms, these patients underwent a surgery to separate the left and right hemispheres. Similar surgeries still happen today.

Later research on this type of surgery showed that the separated hemispheres of split-brain patients could process information independently. This raises the uncomfortable possibility that the procedure creates two separate minds living in one brain.

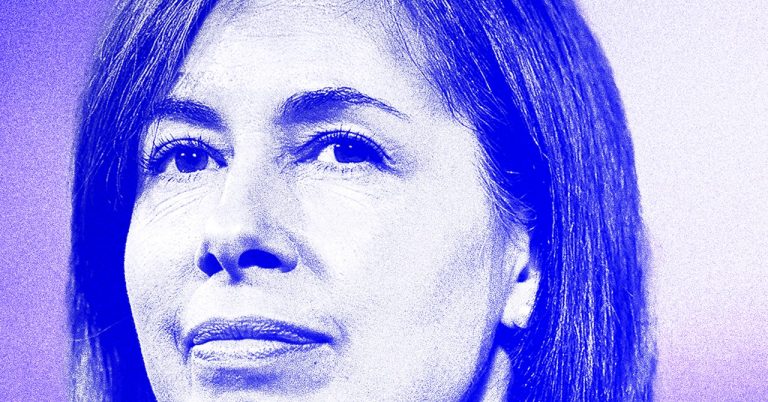

In season one of Severance, Helly R (Britt Lower) experienced a conflict between her “innie” (the side of her mind that remembered her work life) and her “outie” (the side outside of work). Similarly, there is evidence of a conflict between the two hemispheres of real split-brain patients.

When speaking with split-brain patients, you are usually communicating with the left hemisphere of the brain, which controls speech. However, some patients can communicate from their right hemisphere by writing, for example, or by arranging Scrabble letters.

A young patient in one study was asked what job he would like in the future. His left hemisphere chose an office job making technical drawings. His right hemisphere, however, arranged letters to spell “automobile racer.”

Split-brain patients have also reported “alien hand syndrome,” where one of their hands is perceived to be moving of its own volition. These observations suggest that two separate conscious “people” may coexist in one brain and may have conflicting goals.

In Severance, however, both the innie and the outie have access to speech. This is one indicator that the fictional “severance procedure” must involve a more complex separation of the brain’s networks.

An example of a complex separation of function was described in the case report of Neil, in 1994. Neil was a teenage boy who had a number of difficulties following a pineal gland tumor. One of these difficulties was a rare form of amnesia. It meant that Neil could not recall the events of his day or report what he had learned in school. He had also become unable to read, although he could write, and he was unable to name objects, although he could draw them.

Astonishingly, Neil was able to keep up with his education. Researchers became interested in how he was able to complete his schoolwork despite having no memory of what he was learning. They quizzed him about a novel he was studying at school, Cider With Rosie by Laurie Lee. In conversation, Neil could not remember anything about the book—not even the title. But when a researcher asked Neil to write down everything he could remember about the book, he wrote “Bloodshot Geranium windows Cider with Rosie Dranium smell of damp peppar [sic] and mushroom growth”—all words connected to the novel. As Neil could not read, he had to ask the researcher: “What did I write?”

+ There are no comments

Add yours