Unlock the White House Watch newsletter for free

Your guide to what the 2024 US election means for Washington and the world

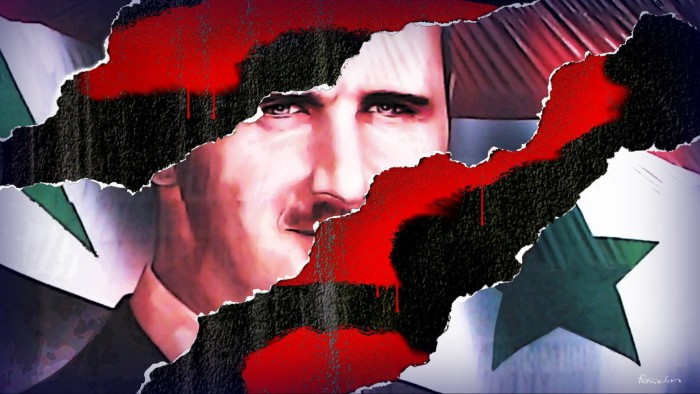

“Assad must go,” said Barack Obama in 2013. More than a decade later, the Syrian dictator has gone. But the mood in the US and Europe is wary rather than celebratory.

Recent history in the Middle East gives good ground for caution. The toppling of other dictators, such as Saddam Hussein in Iraq and Muammer Gaddafi in Libya, was followed by violent chaos rather than peace and stability. The fact that the force that defeated Assad, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), is classified as a terrorist group by the US, UN and a number of European countries adds an extra layer of apprehension. Memories of the rise of Isis in Syria and Iraq in 2014 are also still fresh.

Although they would not say it out loud, the US and the Europeans would probably have preferred the devil they know, Assad, to the uncertainties of a new order in Syria in which HTS is the most powerful force. “Reformed jihadis sounds like a contradiction in terms to me,” says one European leader.

The United Arab Emirates explicitly came out in support of Assad last week. Even Israel — which has contributed mightily to Assad’s troubles, by decimating his Hizbollah allies in Lebanon — would have preferred the old regime to the new dispensation. Yoram Hazony, an Israeli academic close to Benjamin Netanyahu, calls HTS “al-Qaeda adjacent monsters” and says that its success is a “catastrophe”. In fact, the only powerful regional actor that is firmly behind HTS is the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey.

But for both humanitarian and geopolitical reasons, it is wrong-headed for western outsiders to regret the fall of the Assad regime. It was perhaps the most brutal government in a region full of ghastly regimes. More than 500,000 people have died in Syria since the outbreak of the civil war in 2011 — and over 90 per cent of the victims were killed by the Syrian government and its foreign allies.

The thousands of political prisoners in Assad’s jails, where torture and murder were routine, are now emerging into freedom and their stories will be horrifying. The civil war prosecuted by Assad led millions of Syrians to flee the country, creating a refugee crisis that destabilised the EU and generated severe tensions in Turkey. Syria under Assad also became a centre for transnational crime and the drugs trade.

The fall of Assad is also a significant blow to both Russia and Iran. Vladimir Putin’s successful military intervention in Syria in 2015 sent out a message that Russia was back as a global power. Putin’s unchallenged display of power and ruthlessness in Syria helped to embolden him for the subsequent full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. By contrast, Moscow’s retreat and failure in Syria underline how the war in Ukraine has stretched Russia’s resources — and undermine the idea that the tide of international affairs is flowing in Putin’s direction.

The setback for Iran is even more grievous. In recent decades, the Iranian regime has built up a powerful and malign network of proxy forces across the Middle East. But Iran’s proxies are now being destroyed one by one. Hamas has been devastated by the Israeli army in Gaza — albeit at a terrible humanitarian cost. Hizbollah is reeling in Lebanon and no longer capable of fighting in Syria. The Iranian ballistic missile attacks against Israel failed. If Iran now loses its powerful position in Syria, Iranian regional power will essentially have crumbled in the space of a few months.

Of course, there are plenty of reasons to be anxious about what happens next. If the Iranian regime loses its shield of regional proxies, it may look for other ways of securing itself — such as an accelerated push to arm itself with nuclear weapons. Renewed fighting could turn Syria into a failed state and spark new flows of refugees. HTS might turn parts of the country into a safe haven for terrorism.

But some western NGOs that have dealt with HTS in the parts of Syria it already controlled have found it well-organised, pragmatic and ready and able to engage with the outside world. They caution against any assumption that HTS will turn out to be al-Qaeda in a new guise.

The west’s cautious reaction to the fall of Assad reflects the dashed hopes of the Arab uprising of 2011. Syria’s descent into a brutal civil war back then remains a cautionary tale, cited by those who warn against naive optimism about the fall of authoritarian regimes in the Middle East.

But there is also such a thing as naive pessimism. Believing that Assad was firmly in power and that Syrians and the wider region could expect nothing better than perpetual brutal repression was not just cynical — it was also analytically wrong. Saudi Arabia, which reopened an embassy in Damascus earlier this year, was a high-profile example of a government that decided to come to terms with Assad just as his grip on power was about to collapse. It has taken the backwash from the war in Lebanon to show just how brittle the Assad regime’s grip on power was.

Amid all the understandable anxiety about the future of post-Assad Syria, it is easy to lose sight of a simple truth. The fall of a brutal regime that is aligned to other brutal regimes is a good thing.

+ There are no comments

Add yours