It was heralded as the year of democracy. With more than one and a half billion ballots cast in elections across 73 countries, 2024 offered a rare opportunity to take the social and political temperature of almost half of the world’s population.

The results are now in, and they have delivered a damning verdict on holders of public office.

The incumbent in every one of the 12 developed western countries that held national elections in 2024 lost vote share at the polls, the first time this has ever happened in almost 120 years of modern democracy. In Asia, even the hegemonic governments of India and Japan were not spared the ill wind.

Incumbent or otherwise, centrists were frequently the losers as voters threw in their lot behind radical parties of either flank. The populist right in particular surged forward, fuelled in significant part by a rightward shift among young men.

The results paint a picture of angry electorates stung by record inflation, fed up with economic stagnation, disquieted by rising immigration, and increasingly disillusioned with the system as a whole.

In a sense, the year of democracy produced a cry that democracy is no longer working, with the younger generation, many voting for the first time, delivering some of the strongest rebukes against the establishment.

On average across the developed world, incumbents’ vote share fell by seven percentage points in 2024, an all-time record and more than double the decline as electorates punished elected officials in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

The range of countries producing similar results points to a common undercurrent, with inflation the obvious culprit.

Coming into 2024, high and rising prices were the public’s top concern in the vast majority of the countries going to the polls. While recessions are deeply unpopular, their impacts are unevenly distributed. Inflation stings everyone.

But if the cost of living crisis acted as a handicap on incumbents, a closer look across different countries and regions shows that it was far from the only driver of discontent.

The biggest backlash against a sitting government came in Britain, where the Conservatives’ charge sheet included not only high prices but a corruption scandal, a crisis in public healthcare provision, a self-inflicted economic shock and a sharp spike in immigration.

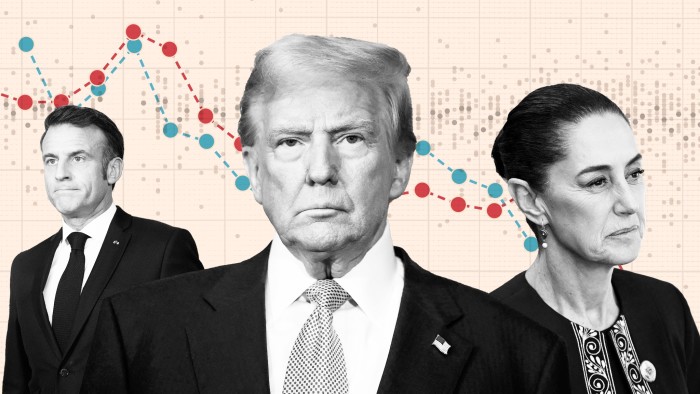

Across the channel in France, president Emmanuel Macron’s attempt to fend off the populist right by calling snap legislative elections backfired. The resulting political chaos is yet to be fully resolved months later.

In India, Narendra Modi’s formidable Bharatiya Janata party machine secured a narrow victory but lost its parliamentary majority, struggling to hold back the tide of dissatisfaction over the increasing disconnect between strong economic growth and weak job creation.

This was particularly pronounced among young people, whose unemployment rate climbed to almost 50 per cent ahead of the election, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

Even the exceptions to the anti-incumbent wave are less anomalous when considered in the context of other central themes of the year’s political shifts.

In Mexico and Indonesia respectively, Claudia Sheinbaum and Prabowo Subianto each improved upon the margin of the sitting president. In both cases, they ran broad campaigns pledging continuity with their anti-elitist predecessors, illustrating the near-universal success of populists over the past twelve months. Prabowo also leaned heavily on dominance of the new social media landscape, another common theme.

Viewed across the world as a whole, the weak performance of centrist parties and the march of populists, particularly on the right, was just as strong a theme as the anti-incumbent wave, perhaps stronger.

Even the Labour party’s victory in Britain is no exception here, as it won this year with fewer votes than in either of the two previous elections it lost. And just months after a landslide victory, opinion has turned sharply against both party and leader.

The French public’s souring on Macron and his centrist party, meanwhile, reflects the wider global mood of disillusionment with the political establishment, and the sense that elected officials either don’t know or don’t care what ordinary people think.

Although ultimately falling narrowly short of its hoped-for victory, the 15-point swing achieved by France’s Rassemblement National in parliamentary elections was the largest recorded by any party in any developed country this year. The second, third and fourth-biggest gains of the year were all by fellow rightwing populists in the form of Austria’s Freedom party, Britain’s Reform UK and Portugal’s Chega.

This speaks to the fact that immigration has been a rising concern across the developed world in recent years, and was one of the key issues on voters’ minds as they went to the polls.

Where conservative parties lost ground, it was generally parties outflanking them on the right who were the main beneficiaries. The success of Nigel Farage’s Reform UK in peeling off Conservative voters in Britain has been widely attributed to the latter’s failure to meet its promise to reduce immigration numbers.

But anti-establishment successes were not limited to the right. The Greens in the UK were one of a smattering of radical leftwing parties that also gained ground as voters disillusioned with a stale centre broke in both directions.

While the timing and magnitude of the anti-incumbent wave point primarily to the short-term shock of higher prices, the populist surge looks more like the continuation — or perhaps acceleration — of a trend that has been playing out in a growing number of countries over two decades at least.

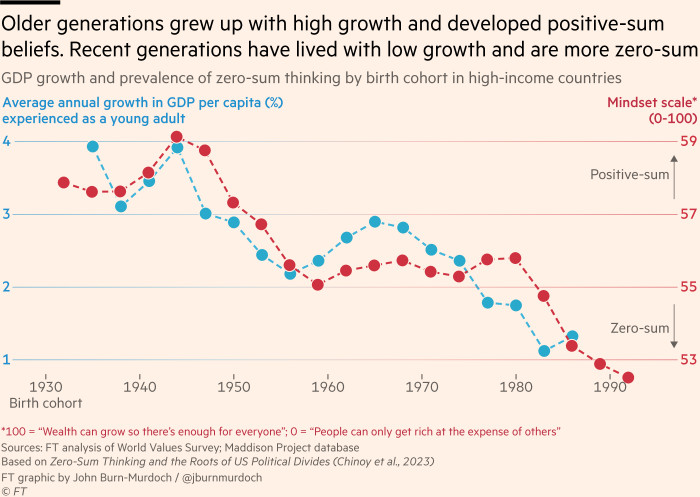

One prominent theory for why we’re seeing this unfold was laid out in an influential paper published earlier this year by a team of Harvard economists, who found that people who grow up against a backdrop of weaker economic growth and less progress between generations are more likely to view the world as zero sum, where one person’s gain must come at someone else’s cost.

The steady decrease in upward economic mobility in rich countries could thus explain much of the rise in these views, which tend to be associated with support for parties and politicians on both left and right that promise to tear up the existing system or to protect against external threats.

One further possibility is that the dramatic changes to the media landscape over the past two decades have played a part in eroding previously long-standing norms against populist rhetoric and talking points. The emergence of social media has made it easier for political outsiders to speak directly to the public, levelling a playing field that had previously tilted towards established figures and parties.

Beneath the surface of the headline results, one of the most striking patterns seen in country after country has been the rise in support for the populist right among young men.

In Britain, support for Reform is now higher among men in their late teens and early twenties than among those in their thirties, and a marked gender gap has opened up among the youngest voters. A very similar pattern can be seen in the US, where young men also swung sharply towards Donald Trump in November, and the same pattern appears across much of Europe.

Notably, there appears to be plenty of room for this trend to continue: the share saying they would consider voting for the radical right is even higher than those who already have.

Such a pronounced shift is startling, but is not without plausible explanation. If discontent with economic stagnation drives zero-sum attitudes, few groups have experienced such a flatlining as young men, whose relative socio-economic status has been in steady decline across the west.

But it’s not only young men moving to the extremes. Young women in the US also swung towards Trump, while in the UK they shifted heavily to the Greens.

This fits with research from the polling company FocalData earlier this year, which found young people far more likely than their elders to support a hypothetical national populist party, and a 2020 study which found satisfaction with democracy in the developed west plummeting further and faster among young adults than any other group.

All indications are that both defining trends of 2024 are set to continue next year. The latest polls show the incumbent governments of Australia, Canada, Germany and Norway all on course to lose power in the coming months.

And in most of these countries it is once again the populist right that looks set to make the biggest gains. Norway’s rightwing populist Progress party currently leads after finishing fourth in 2021, and Germany’s AfD are currently polling in second place.

The acute inflation crisis may have passed, but with stubbornly weak economic growth, a widening generational wealth gap and a fragmented media, 2024 may prove to be less an anomaly than one particularly jagged point on a downward trend.

+ There are no comments

Add yours