Entertainment

10 Greatest Movie Masterpieces of the Last 75 Years, Ranked

Like any art form, cinema occasionally produces works that feel larger than their medium. These are the true classics, the movies reshape how we see the world. They shape entire generations, birth countless copycats, and might even change culture itself. More importantly, they’re the movies that inspire future artists to embrace cinema and, in it, find a new purpose in life.

With this in mind, this list attempts to rank the very best films of the last 75 years (no easy task, to be sure). The masterpieces below span a range of genres and tones and come from both the US and abroad. They are all ambitious in their own way, whether that’s through stylistic experimentation or depth of emotion, representing the most essential of essential viewing.

10

‘8½’ (1963)

“Happiness consists of being able to tell the truth without hurting anyone.” Federico Fellini’s 8½ is one of cinema’s most vivid explorations of the creative process, both the beauty of it and the agony. The story revolves around Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), a famous Italian director struggling with artistic block while preparing his next movie. Torn between reality, memory, and fantasy, Guido wanders through his subconscious, surrounded by lovers, muses, and critics who demand meaning he no longer possesses.

From here, the narrative dissolves into dream logic. Federico hits us with circus imagery, surreal sequences, and hypnotic music from Nino Rota. It makes for an intense self-portrait of genius and confusion, drawing heavily on Fellini’s life. In other words, 8½ is the ultimate movie about making movies, yet it also has a lot to say about the fragility of human identity. Countless filmmakers since have borrowed from its playbook.

9

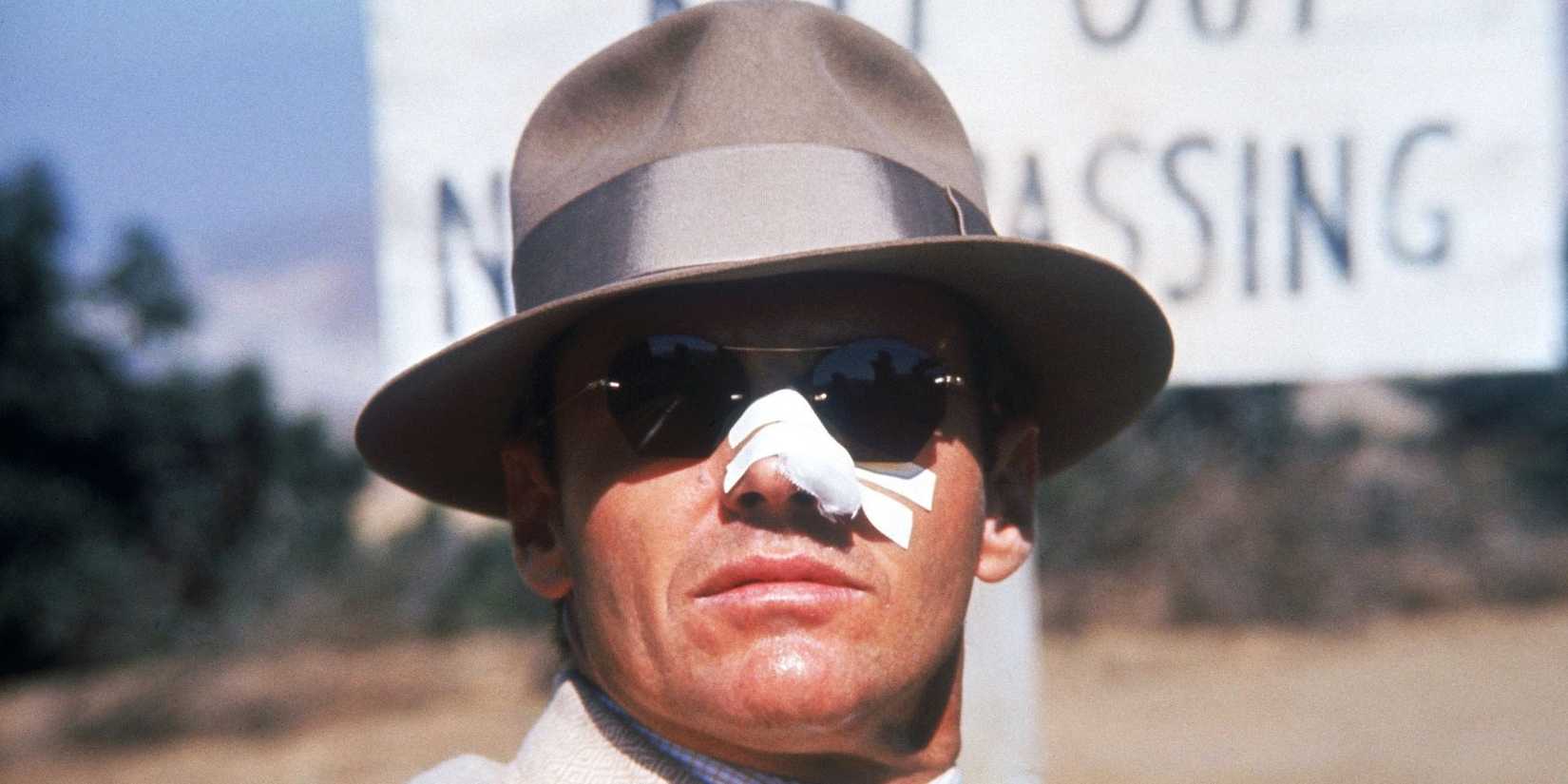

‘Chinatown’ (1974)

“How much are you worth?” Chinatown begins as a stylish 1930s detective story and ends as a modern Greek tragedy. Jack Nicholson delivers one of his finest performances as Jake Gittes, a private eye hired to investigate an affair, only to uncover a labyrinth of corruption, incest, and political rot beneath Los Angeles’ sunlit façade. The screenplay by Robert Towne is often hailed as the greatest ever written. It’s tight, complex, and devastating, structurally inventive and rich in character. Every line carries double meaning, every clue leads closer to moral collapse.

Opposite Nicholson, Faye Dunaway is also fantastic as the tormented Evelyn Mulwray, while John Huston’s Noah Cross is smiling, paternal, and absolutely evil. Chinatown ends not with triumph but futility: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” All this makes the movie the definitive neo-noir: beautiful, fatalistic, and utterly without redemption, the ultimate mirror held up to the cynical 1970s.

8

‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979)

“I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” The Godfather duology not having sated his ambition, Francis Ford Coppola took on his most Herculean challenge: a Vietnam War epic, shot in the jungle, with a sprawling A-list cast. The finished product, forged in mayhem, is both a military epic and a full-on fever dream. Loosely based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the plot follows Captain Willard (Martin Sheen) as he travels upriver to assassinate the rogue Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), who has gone insane in the jungle.

That said, the story is less important than the mood and aesthetics. Apocalypse Now isnot about Vietnam; it is Vietnam, as Coppola famously said. The production itself became legend, nearly destroying its creator, yet what emerged is a work of operatic scale and moral terror. Apocalypse Now captures humanity’s attraction to horror and its willingness to worship the very destruction it fears.

7

‘In the Mood for Love’ (2000)

“Feelings can creep up just like that. I thought I was in control.” Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love is one of the most achingly beautiful films ever made. Set in 1960s Hong Kong, it centers on two neighbors, Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung), who realize their spouses are having an affair. As they grow closer, they reenact what their partners might have done, but vow never to cross the same line. Theirs is a near-romance, one where every glance, silence, and movement becomes charged with longing.

The aesthetics complement the themes perfectly. Christopher Doyle’s cinematography turns narrow hallways and rain-soaked streets into emotional landscapes, while Shigeru Umebayashi’s waltz theme loops like a heartbeat. Even though little happens, every frame is shot through with feeling. Wong crafts the simple premise into a meditation on restraint, memory, and the spaces between people.

6

‘Schindler’s List’ (1993)

“Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” In Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg transformed his gift for spectacle into moral witness. It recounts the true story of Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson), a German businessman who initially profits from the Nazi regime before risking everything to save over a thousand Jews from extermination. Filmed in stark black-and-white by Janusz Kamiński, the movie juxtaposes beauty with atrocity, orderly bureaucracy and unspeakable cruelty. The girl in the red coat, a flash of color amid monochrome death, remains one of cinema’s most haunting symbols.

On the acting front, Ralph Fiennes is chilling as Amon Göth, a sadist who embodies systemic evil, while Neeson’s Schindler evolves believably from opportunist to savior. All this makes Schindler’s List not just a masterpiece of craft but of conscience. It insists on remembering. Spielberg takes on difficult material (this was by far the most dramatic movie he had made at that point) and makes great art for it.

5

‘Psycho’ (1960)

“We all go a little mad sometimes.” When Psycho dropped in 1960, it blew the rules of filmmaking wide open, defying audience expectations on multiple levels. It begins as a crime thriller: Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals money and flees town. Halfway through, she’s brutally murdered in the shower, and the story shifts to Norman Bates (a fantastically eerie Anthony Perkins), a shy motel owner with secrets buried deeper than the swamp. While this narrative switcheroo was provocative for the time, the sound and imagery were no less groundbreaking.

Hitchcock weaponized editing, sound, and misdirection, using Bernard Herrmann’s shrieking violins and rapid cuts to practically invent modern horror. Six decades later, its black-and-white images still slice through the screen. Not to mention, the character of Norman, simultaneously victim and monster, chill and killer, would become a horror archetype, spawning countless copycats but arguably no equals.

4

‘Pulp Fiction’ (1994)

“Say ‘what’ again. I dare you, I double dare you!” Speaking of cinematic rule-breaking, the irreverent wunderkind of ’90s cinema was undoubtedly Quentin Tarantino, and this epic might just be his masterpiece. Told through interlocking stories of hitmen, boxers, and small-time crooks, Pulp Fiction resurrected the crime genre with dazzling dialogue and non-linear structure. John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman, and Bruce Willis deliver career-defining performances, weaving violence and humor into something hypnotically cool.

Tarantino mined pop culture for cinematic alchemy, serving up a strange blend of movie references, Bible verses, burgers, dance scenes, and unexpected redemption, all stitched together with irony and soul. It shouldn’t work, but somehow does. Here, style is substance and chaos is coherence. Pulp Fiction‘s genius lies in tone, funny, shocking, and strangely humane all at once, and its obvious affection for the medium. QT draws on dozens of films here, not to copy them but to pay homage to them, and ultimately, transcend them.

3

‘The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King’ (2003)

“There’s some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for.” The grand summit of cinematic fantasy, a culmination of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic world and one of the most ambitious productions ever mounted. The movie delivered all the big story beats fans had been waiting for: Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin) reaching Mount Doom, and Aragorn (Viggo Mortensen) rising to claim his destiny as king. Along the way, we get massive battles and intimate emotion, from Gollum‘s (Andy Serkis) torment to Sam’s devotion.

With these movies, Peter Jackson achieved something truly remarkable. Here, practical effects, miniatures, and digital innovation all serve a story about courage, corruption, and fellowship. And, more than two decades later, most of the visuals still look great (arguably better than most of what we see at the cineplex today). All in all, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King is modern myth-making at its purest.

2

‘The Shawshank Redemption’ (1994)

“Get busy livin’, or get busy dyin’.” The Shawshank Redemption begins in despair and ends in grace. Adapted from Stephen King’s novella, it tells the story of Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins), a banker wrongfully imprisoned for murder, and his friendship with Red (Morgan Freeman) over decades inside Shawshank Prison. Within its gray walls, hope seems impossible, but Andy’s quiet defiance slowly transforms the lives around him. Frank Darabont handles the material with tenderness and moral clarity.

The film’s emotional power lies in its belief that patience and goodness can outlast cruelty. Its final sequence (Red’s narration, the blue ocean, the reunion on the beach) is among the most cathartic in cinema. Though overlooked on release (Forrest Gump and Pulp Fiction got most of the attention at the time), Shawshank has become one of the most beloved films ever made. It’s literally the highest-rated film on IMDb. It’s a feel-good movie that restores your faith in the universe, even if just for a while.

1

‘The Godfather Part II’ (1974)

“Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.” The Godfather Part II is both sequel and prequel, tracing the rise of young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) alongside the moral decay of his son Michael (Al Pacino). Taken together, these parallel narratives make a poignant statement on power, inheritance, and the slow corrosion of the soul. The film expands the world of The Godfather into something mythic: the American Dream as family tragedy. It’s Shakespearean in scale without ever being melodramatic (a flaw that would undermine Part III).

At the eye of the storm is Pacino. His performance here is chilling, utterly believable as a man who gains everything and loses himself completely. On the aesthetic side, Gordon Willis’ cinematography cloaks the story in golden light and funereal shadow, while Nino Rota’s mournful score deepens every betrayal. In its cold precision and emotional grandeur, it remains the greatest example of what cinema can achieve when ambition meets art.