Travel

Italy’s Emilia Romagna in seven luxurious tastes

Foodies talk of Emilia Romagna‘s produce with religious awe. Cathedrals of cheese. Heavenly wine cellars. God-given truffles.

Tastes that have endured for centuries, sometimes millennia: balsamic vinegar, prosciutto, parmigiana reggiano, lambrusco, pasta, tomatoes and truffles. A gourmet’s directory of 26 food museums, 24 DOC wines, plus numerous festivals of prosciutto, truffles and more.

Throw in the dramatic architecture of Bologna, Modena and Parma, with an operatic soundtrack, and Emilia Romagna is a dream destination for the ultimate foodie road trip.

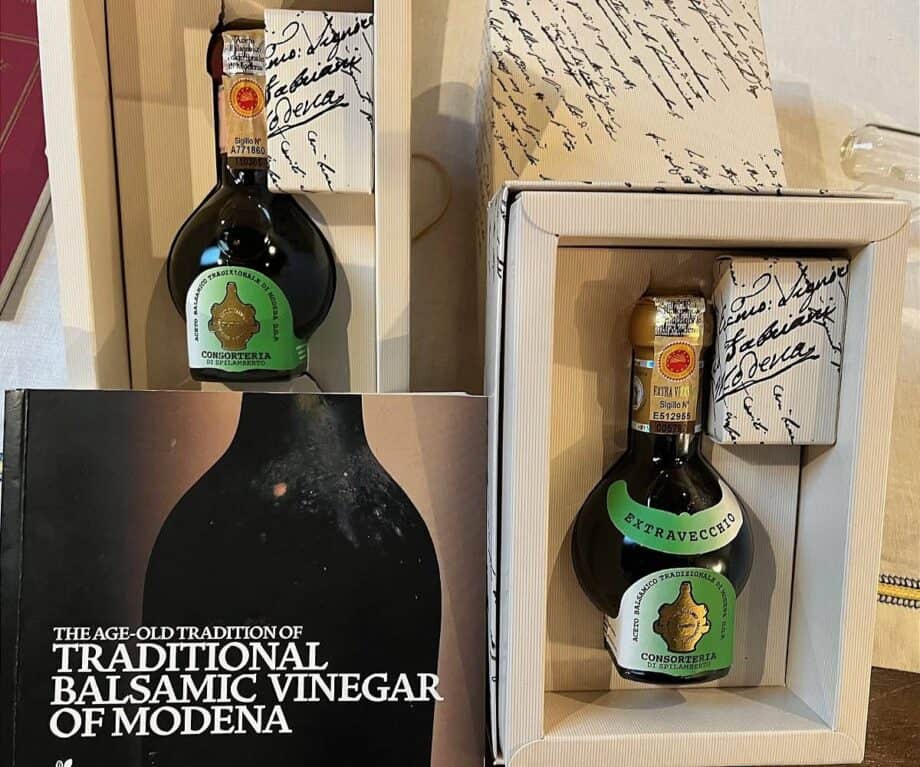

Balsamic vinegar

Drop the vinegar. They simply call it balsamic round these parts as it is a balm that soothes and restores: albeit at a price.

True balsamic, like a fine wine, has a protected origin, a DOC. If you’re putting a bottle of balsamic vinegar in your supermarket trolley, to serve as a salad dressing, it’s unlikely to be one of the region’s finest.

Balsamic creators claim that there is only one ingredient: grapes boiled for many an hour. That isn’t strictly true, they are being modest. When bottles are stored for 12 or 25 years, time and care are key ingredients too. Everyday the barrels are inspected and frequently turned.

Such vintages are not used as a salad dressing. Balsamic is dripped onto aged Parmigiana Reggiano as a starter. Drizzled onto strawberries, ice cream or panna cotta for dessert. For many, a drizzle of 12 year old balsamic over mature Parmigiana Reggiano is “La sua morte”, as good as it gets in this life, the perfect pairing.

In Modena, home of Ferrari, the style flows into the vinegar too: the iconic round bottles were created by a car designer back in 1987.

One long held tradition is to lay down a balsamic battery, a set of barrels, to celebrate the birth of a baby. As the child matures, so does the balsamic.

Prosciutto

In Emilia Romagna, cafe society talk often boasts of how their town has the best prosciutto.

Take a look at Modena Cathedral which leans away from its tower. Frescoes around one of the entrances, probably dating back to the 12th century, show a calendar of a peasant’s year.

As barren winter took hold in January, the diligent peasant should be carving a pig’s leg to produce cured prosciutto to see his family through the hungry winter months.

The mists of the River Po, the same fog that allegedly saved Modena from Atila the Hun’s rampaging hordes, contribute to the curing process. Food is history in Emilia Romagna: history is food.

Parmigiana Reggiani

In this region they don’t say cheese when it’s time to pose for a photograph they say, “Parmigiana Reggiano”.

Remember that you are on a “farm”. Never ever say “cheese factory.” Creating Parmigiana Reggiano, is a hands-on, artisan skill. Cheesemakers are like muscular midwives giving birth to two 50 kilogram wheels of cheese known as twin girls.

Originally, Benedictine monks aimed to create a long-lasting cheese. After soaking in brine, which takes nine months to seep through to the centre, the great wheels of cheese are stored in cheese cathedrals. Wheels are turned every week, ideally sweating away through two summers. In fact, there is a cathedral hush, as talking is not permitted amongst the cheeses in case it spreads infection.

Skilled inspectors gently tap the cheeses with a hammer, cheese orchestra percussion, to check there are no holes. Over two years, a cheese will slim down from 50kg to 40kg. As it ages, the structure changes, giving more crystals.

Young cheeses move-on to retailers whilst others progress to a cheese bank, often owned by banks, where they are kept as collateral against the farmers’ debts. More mature three and four year old cheeses are used for stuffing pastas such as tortellini.

Everything you need to plan your trip in 2024

Lambrusco

Forget memories of the cheap, sweet, fizzy pop that you drank at teenage parties.

Authentic Lambrusco, grapes originating from six different appellations within Emilia Romagna, is a drier, far more sophisticated wine.

“A nose of citrus and pomegranate. Sharp acidity. Impressive length. I’m biting through it for a fourth time,” says Filipino Bartolotto as he guides us through our first Lambrusco. “Even for professionals this is a wine that is difficult to spit,” explains the tasting master and wine journalist.

“Now we move to another world,” he says picking up a glass of Lambrusco red. “Prunes and shades of beetroot. An inky driven nose.”

Raising a glass to Lambrusco, “Chin-chin,” he exhorts. Before heretically recommending that some Lambrusco wines pair very well with … pizza.

Dynamic young winemakers are taking Lambrusco ever onward. As well as using SuFriGradi, the F1 Grand Prix term for a car accelerating to peak performance, the wine’s bottle is exactly the same height as a Ferrari F1 piston.

Barilla pasta

Early morning, as you walk through the grand arched porticoes of Modena, peep through restaurant windows to see women cajoling, nudging and shaping the day’s pasta.

For Barilla, pasta is art. They have employed Fellini and Lynch to bring art-house production values to their commercials.

At the Academia Barilla, in Parma, chef Marcello prefers his pasta al dente, with a slight bite. He dismisses the Neopolitans who cook their pasta so briefly that it is crunchy whilst also disparaging the Milanese who go beyond al dente to soft.

In Parma, Barilla’s original shop is open to visitors to learn the history of Italy’s most famous pasta. Within walking distance is the Academia Barilla and its library of 26,000 food themed books and 5,000 menus: open to the public, by appointment, on Mondays.

Yet, Marcello thinks beyond the box, reinventing pasta. Overcooking fusilli for 25 minutes, chilling it in iced water, oven-drying at 50 centigrade and finally frying it for just three seconds creates a popcorn like snack.

Mutti tomatoes

Throughout the Po River region, 400 tomato growers aspire to the Golden Tomato awarded from

Mutti. Competition for the €7m paid annually in incentives encourages suppliers to produce the very best fruit for Mutti’s chopped tomatoes and tomato paste.

In 1899 the Mutti family decided to focus on tomatoes and now their latest project has been creating “A place to eat” canteen. Soon the tomato-resin floored, Carlo Ratti designed building, will open in the evenings as a restaurant overseen by the Famiglia Cerea: a renowned name guaranteeing serious quality.

The entrance to the canteen, with echoes of Andy Warhol’s iconic work, is a wall of Mutti tins.

Truffles

There’s a mystique to truffle-hunting. Luigi Dattioli, now managing of Appennino Foods, searched for a year before his first truffle.

Even wellied truffle hunters with a lifetime’s experience can draw a blank as their Lagotta Romagnolo dogs sniff amongst the roots of poplar, oak, hazelnut and hornbeam trees.

Many truffle hunters prefer female Lagottas, as they are said to focus better than the males, keeping a treat of mortadella or prosciutto in their pocket to distract them from the truffles they discover.

In the hierarchy of the truffle world, white truffles are the most highly prized, fetching as much as €5,000 per kilo on a fluctuating market. Yet, very few hunters are able to make a living from truffles alone.

A culinary hotspot

The rich-soiled swathe of land, Emilia Romagna, slashing diagonally across Northern Italy from the Adriatic towards the Mediterranean puts the epic in epicurean. It is home to Bologna which many claim is the food capital of the world. Yet, it is Parma which UNESCO has designated a world gastronomic society.

The ancient Via Emilia hosts a line of towns and cities, each with its own gastronomic heritage, creating Italy’s Food Valley. One of the planet’s culinary hotspots.

Disclosure: Our visit was sponsored by Emilia Romagna Tourism.

Did you enjoy this article?

Receive similar content direct to your inbox.

Travel

Why you want to book a windowless ‘inside’ cabin on a cruise ship

As regular readers know, I’m a big fan of cabins with balconies. As I explained in a recent story, there’s nothing quite like being able to step onto a balcony on a ship to breathe in the fresh ocean air.

But that doesn’t mean I’m opposed to the idea of staying in a cabin without a balcony. In fact, at times, I’ll even book a cabin that doesn’t have a window — or, as they’re known in the cruise world, an “inside” cabin.

If you’ve never been on a cruise before, you might not even know there’s such a thing as a cabin without a window. But there is, and they’re actually quite common. Many ships operated by major lines such as Royal Caribbean and Norwegian Cruise Line have hundreds of windowless cabins.

That may seem almost unthinkable to people who are used to staying at hotels on land. After all, there aren’t a lot of hotels that have hundreds of rooms without windows. If there were, we’re guessing they wouldn’t be huge sellers.

But it’s fair to say that accommodations on cruise ships have their own set of quirks.

The upside of an inside

The lack of a window isn’t the only reason to pooh-pooh the idea of staying in an inside cabin.

In addition to offering nary a peek at the world, inside cabins — named because they’re generally located toward the middle of ships, away from exterior walls — also often are the smallest cabins on any cruise ship. Many are downright tiny. That latter point can be a big turnoff for some cruisers.

But there are advantages to inside cabins, too. For starters, inside cabins often are significantly less expensive than ocean-view cabins. They also offer a sort of “less is more” minimalism that can appeal to a keep-it-simple crowd.

Related: 5 reasons to turn down a cruise ship cabin upgrade

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

For me, at least, there are times when a cabin that’s inexpensive and modest in size is just fine, even if it doesn’t have anything in the way of a view.

After all, for the most part, I’m not taking cruises to spend a lot of time in a cabin. Like most cruisers, I get on ships to enjoy all they have to offer in their public spaces and to explore all the wonderful places to which they sail.

In that context, does it really matter if the room where I’ll sleep each night is big and fancy?

Related: The 5 most desirable cabin locations on any cruise ship

To steal a line from Arthur Frommer, the legendary guidebook author and guidebook company founder, “Most of the time you’re in your room on vacation, your eyes are closed.”

Frommer said that to me years ago during an interview about his favorite hotel rooms. He thought spending huge sums on fancy digs was a waste. His words stuck with me over the years, and now I see their wisdom.

Here are six reasons you might want to seriously consider the least expensive inside cabins on any cruise ship.

You’ll save money

This is, for sure, the big allure of inside cabins. They can be an incredible deal.

At the time of this story’s publishing, fares for inside cabins on six-day Royal Caribbean cruises out of Fort Lauderdale in January 2026, for instance, were available for about 20% less than fares for balcony cabins. The fares for inside cabins were less than half the cost of the least expensive suite.

Specifically, you could get on the line’s amenity-packed Allure of the Seas out of Fort Lauderdale on a Jan. 11, 2026, departure for $760 per person, if you were willing to stay in an inside cabin. That works out to just $109 a day.

Related: Royal Caribbean cruise ship cabin and suite guide: Everything you want to know

The thing to remember here is that all of Allure of the Seas’ major attractions, from deck-top pools and surfing simulators to an indoor ice skating rink and a giant theater with Broadway-style shows, are open to everyone on board, whether they’re staying in the smallest or biggest cabin. So are nearly all the ship’s onboard restaurants, bars and lounges.

Other than having to sleep in a smaller, windowless room, you’ll be getting much of the same onboard experience as someone who pays far more for a snazzy cabin but at a fraction of the price.

You’ll sleep like a baby

There is no dark in the world like the dark of an inside cabin. Once you turn off the lights, it will be pitch black — the kind of darkness that’s almost scary to contemplate.

This can be a bit disorienting for someone who’s used to at least a little moonlight getting into the bedroom at home. But if you’re the kind of person who has trouble sleeping with any kind of light disruption, an inside cabin can be pure bliss. You’ll go to bed without any worry about the morning sun sneaking through your curtains to wake you prematurely. And moonlight is definitely not a problem.

Related: 8 cabin locations on cruise ships you should definitely avoid

Inside cabins can be particularly appealing if you’re sailing far north around the summer solstice when the sun stays up for much (or all) of the day. We’re talking about places like Alaska, the Norwegian coast and around Iceland and Greenland. Ditto if you’re sailing far south during the winter to places such as Antarctica or the more southerly parts of South America.

You’ll spend more time enjoying the ship

The trick to having a blast on a cruise ship is to dive right into anything and everything it has to offer. If it has a rock wall, you need to climb it. Karaoke? Get ready to sing. Leave no waterslide or late-night comedy show unexperienced. To do this, of course, you need to get out of your room, and there’s no better motivation to venture out of your room than to have one that lacks much space or even a window.

When I book inside cabins, I find that I get up and out early. Instead of ordering room service for breakfast, I’ll head to a restaurant with a view and then explore the ship more than usual in the morning. I’ll spend daytime hours playing on the ship’s top decks and evening hours out late at the bars, lounges and showrooms.

Related: 7 reasons you should splurge for a suite on your next cruise

By offering you little more than a small, dark place to rest your head at night, inside cabins can be just the impetus you need to make the most of your cruise vacation.

You might get less seasick

Worried about getting seasick on your next cruise?

The most stable place to be on any cruise ship is low down on the vessel near its equilibrium point, which is generally near its center. Since inside cabins are closer to the center of a ship than “outside” ocean-view and balcony cabins, they can be more stable in rough seas. The trick is to find an inside cabin toward the center of the ship in both directions — lengthwise and widthwise.

The counterargument to this, for the record, is that you can’t look at the horizon when you’re in an inside cabin — a common tip for people experiencing seasickness. And you won’t have access to fresh air as you would in a balcony cabin.

If you’re solo, you might avoid extra fees

Nearly all cruise ship cabins are designed for two travelers, each paying their own fare, and solo travelers generally have to pay an extra fee to stay in one alone. But some ships have special inside cabins specifically designed for solo travelers. If you’re traveling alone and stay in one of these special cabins, you can avoid the extra solo traveler fee, known in the industry as the “single supplement.”

Norwegian, which has been at the forefront of the solo cabin trend, now has hundreds of inside cabins for solo travelers spread across more than half a dozen vessels.

Related: 15 ways that cruising newbies waste money on their first cruise

While Norwegian’s solo cabins do have windows, they open up onto hallways, not the outside of the ship. They’re also unusually small, at around 100 square feet, but they’re superbly designed to maximize storage space, too. Additionally, they’re clustered around exclusive lounges where solos can mingle at daily hosted happy hour gatherings.

Royal Caribbean, Cunard and Holland America are among other lines that have been adding solo cabins to some ships — many of them inside cabins.

There are a few ocean-view cabins designed for solo travelers in the industry, but they are very rare.

You might still get an ocean view (with a twist)

On a few innovative cruise ships, there are windowless inside cabins that offer a view of the outside world, thanks to the magic of technology.

On some Disney Cruise Line ships, some inside cabins come with “magical portholes” that show real-time views of the outside. They’re actually screens built into the walls of the cabin to give the illusion of a porthole view.

Royal Caribbean has gone a step further, adding large “virtual balconies” to inside cabins on some ships. These are floor-to-ceiling LED screens that show real-time views of the outside, built into the walls of the cabins in such a way that they offer the illusion of a balcony.

If this idea sounds a little hokey, it is. But I’ve stayed in these cabins, and the illusion is surprisingly real. The addition of the screens really changes the feel of the rooms. The Disney cabins are particularly fun, as Disney characters sometimes make cameo appearances in the magical portholes. If you have young kids with you, they’re going to love it.

Bottom line

Booking a room without a window on a cruise ship might seem like an odd choice. But there are good reasons to consider one, not the least of which is that rooms without windows on cruise ships — known as “inside” cabins — can be an incredible value.

Planning a cruise? Start with these stories:

Travel

Qantas Frequent Flyer announces sweeping changes to loyalty program — here’s what to book now and what to book later

Australian airline Qantas has announced a mixed bag of changes to its loyalty program. Some award rates and carrier-imposed surcharges will increase later this year, but the airline will also add additional award availability and new partner award tickets. Thankfully, these Qantas Frequent Flyer changes won’t take effect until Aug. 5.

Given the news, there are some redemptions you should book now and others that you should wait to book until later this year. Here’s what you need to know about the changes so you can plan accordingly.

Higher prices and surcharges for Classic Flight Rewards

For bookings made from Aug. 5 on, Qantas will increase the cost of its cheapest saver-level redemptions (called Classic Flight Rewards) and saver-level upgrades for Qantas-operated flights by 5% to 20%, depending on the route.

On the shortest domestic routes like Brisbane Airport (BNE) to Sydney Airport (SYD), rates for Classic Flight Rewards will increase from 8,000 points each way to 9,200 points, with the fees, taxes and surcharges of 55 Australian dollars (about $34.50) remaining the same.

The price increase will be more substantial on long-haul services, such as Qantas flights from Sydney to Europe. Bookings made from Aug. 5 on will rise from 144,600 to 166,300 Qantas points each way, and fees, taxes and surcharges will increase from AU$473 to AU$648 (about $297 to $406).

Classic Flight Rewards are often hard to find, especially on long-haul routes in premium cabins. This has been especially apparent since the airline launched dynamically priced Classic Plus Flight Rewards in 2024. These award tickets are tied to the cash price of a flight and are much more expensive.

Verdict: Book now.

Higher redemption rates for partner airlines

Qantas is a member of the Oneworld alliance, meaning you can redeem Qantas points on partner airlines like American Airlines, British Airways and Alaska Airlines. The airline also partners with carriers outside the Oneworld alliance, such as Air France, KLM and Emirates.

For bookings made from Aug. 5 on, Emirates flights will be priced according to the Qantas award chart (rather than the partner award chart). Because of this, award rates and surcharges will increase for Emirates-operated flights, as with Qantas-operated flights.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

Qantas has not yet revealed the price increases of other partner airlines, though it says it will do so in May (for bookings made from Aug. 5 on). Currently, you can book domestic flights within the U.S. on routes like New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) to Charlotte Douglas International Airport (CLT) from just 8,000 Qantas points, a great deal given that other Oneworld carriers have devalued short-haul domestic flights.

If you want to redeem Qantas points on partner airlines, you should do so before the prices rise in August.

Verdict: Book now.

Related: A step up from your average economy: Flying Emirates’ A380 from Dubai to Johannesburg

New premium economy award options

For the first time, starting in October, you can redeem Qantas points for premium economy seats on flights operated by Finnair, Air France, KLM and Iberia. Due to this change, the program promises that 200,000 new premium economy award seats will be added.

If you don’t have enough Qantas points to book business-class award seats on these airlines, you may wish to wait until August to book premium economy seats.

Verdict: Book later.

Related: Is Iberia premium economy worth it on the Airbus A330 from Madrid to Dallas?

New Classic Flight Rewards seats on Hawaiian Airlines

In advance of Hawaiian Airlines’ entry into the Oneworld alliance, you will be able to redeem Qantas points for flights on the airline starting in October.

Qantas promises 800,000 Hawaiian Airlines award seats will be available to Qantas Frequent Flyer members.

Verdict: Book later.

Related: A new era for Hawaiian Airlines as it launches Dreamliner service: TPG was on the inaugural

Lower award prices for Jetstar flights

Jetstar is Qantas’ wholly owned low-cost subsidiary, comparable to Europe’s EasyJet in terms of passenger experience, pricing, rules and restrictions. Jetstar is not a Oneworld alliance member, so partner points or miles cannot be used to book Jetstar flights (nor can you use non-Qantas Oneworld status).

You can already redeem Qantas points for Jetstar flights. However, from Aug. 1 on, the cost of Classic Flight Rewards seats on Jetstar for popular Australian routes like Melbourne Airport (MEL) to SYD will drop to just 5,700 Qantas points.

If you want to get from point A to point B and aren’t fussed about traveling on a full-service airline or using your Oneworld status benefits, this will be an inexpensive way to fly domestically within Australia.

Verdict: Book later.

Changes to earning points

In addition to the above pricing changes, Qantas will increase the number of points members earn on domestic cash tickets by up to 25%. The airline will also award additional points on select international tickets.

Earning Qantas points via credit cards

While there are no Qantas-branded credit cards available in the U.S., you can transfer rewards from three programs with transferable currencies directly to Qantas Frequent Flyer:

Each has a transfer ratio of 1:1, so 10,000 credit card points equal 10,000 Qantas points.

Additionally, you can transfer Marriott Bonvoy points to Qantas Frequent Flyer at a 3:1 ratio, meaning 3 Marriott Bonvoy points become 1 Qantas point. Marriott will also add 5,000 bonus points when you transfer 60,000 Bonvoy points to an airline.

Bottom line

Devaluations are an unfortunate reality of collecting points and miles. We recommend earning transferable points for precisely this reason; if one transfer partner devalues, you can always book with another.

These changes announced by Qantas represent higher prices and surcharges for both flights operated by Qantas and its partner airlines within and outside the Oneworld alliance.

However, there are some upsides. Qantas is giving members six months’ notice before any price increases. And, for the first time, members will be able to book Hawaiian Airlines and premium economy award tickets on several partner airlines.

For flights that will increase in price, you should consider booking as soon as possible.

Travel

United’s wildest route yet is officially on sale

If you’ve been excited about the possibility of flying a United Airlines Boeing 737 to Mongolia, you’re in luck. The airline has just officially started selling flights to Ulaanbaatar.

The Chicago-based carrier just filed the details of this creative new route, as first seen in Cirium schedules.

CIRIUM

United’s new 1,900-mile route from Narita International Airport (NRT) to Chinggis Khaan International Airport (UBN) will commence on May 1 with three times weekly service in each direction. (The westbound service will operate on Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday, while the eastbound flight will operate on Monday, Wednesday and Friday.)

Pro tips: The biggest mistakes people make with travel rewards credit cards

Flights from Tokyo will depart at 4:30 p.m. and land in Ulaanbaatar at 8:55 p.m. The return service will leave at 9:55 a.m. and land in Toyko at 3:45 p.m.

United plans seasonal service in this new market with flights scheduled to end on Oct. 12, 2025.

These flights are timed to connect with United’s primary transpacific departure and arrival banks from Narita. United operates long-haul flights from Narita to Denver, Houston, Los Angeles, Newark and San Francisco.

United will deploy a Guam-based Boeing 737-800 on this route, featuring 16 business-class recliners, 48 Economy Plus extra-legroom seats and 102 standard economy seats.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

Seeing a United Boeing 737 in Mongolia might be puzzling for some, but it’s being operated as part of historical fifth-freedom rights that United has in Tokyo for flights that originate in the U.S. and continue onwards to other countries.

In recent years, United hasn’t really taken advantage of these rights, instead focusing on boosting its hub in Guam. That said, Guam hasn’t been as busy or lucrative as it has in the past, so United seems to be experimenting with new uses for the jets it stations in Micronesia.

Flight review: Is United Airlines premium economy worth it to Europe?

In fact, United has been busy in recent months turning its presence at NRT into a de facto gateway hub within the larger region. The airline recently commenced new flights from Tokyo to Cebu in the Philippines, and now it’s adding three more short-haul regional routes from the airport (Kaohsiung, Taiwan; Koror, Palau; and Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia).

United says that its joint venture partnership with Japanese airline All Nippon Airways will help these routes take off. (For instance, ANA doesn’t currently fly from Narita to Ulaanbaatar.) The new flights will also be supported by travelers looking for one-stop connections from the U.S.

“We are thinking about Tokyo differently than how it’s been thought of in the past. I think Tokyo is a real asset to us. … And when we went through the data, a lot of this traffic was connecting over Beijing, but is not doing so anymore. And so this is a way to connect it over Tokyo,” United’s network chief Patrick Quayle told TPG back when the routes were announced in October.

If you’re looking to book the new route, one-way fares start at $326 in economy and $753 in business class. Introductory mileage rates are quite steep, with one-way economy flights starting at 30,000 miles and business-class flights starting at a whopping 75,000 miles.

There was no saver award availability on the new routes as of time of publication.

Related reading:

Travel

JetBlue Mosaic elite status: What it is and how to earn it

Having elite status with an airline you frequent — such as JetBlue — can make your travels more comfortable, efficient and seamless.

However, since earning elite status often requires a significant commitment of travel time and money, it’s important to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of a frequent flyer program before funneling your business to that airline. For some individuals who are airline free agents, it may not make sense to pursue elite status at all.

This guide will evaluate JetBlue Mosaic status and explain how the status tiers work, how to earn them and whether striving for this status is worth the effort for JetBlue flyers.

Related: Complete guide to airline status matches and challenges

What is JetBlue Mosaic status?

JetBlue rewards the most frequent flyers in its TrueBlue loyalty program with Mosaic status and the TrueBlue points they earn while flying the airline.

Unlike the legacy U.S. carriers, which offer complimentary upgrades on domestic flights to their most loyal members, many of JetBlue’s aircraft are not equipped with its luxurious, well-regarded Mint business-class cabin. Instead, JetBlue elite members benefit from earning bonus points, selecting Even More Space seats and getting free checked bags, among other benefits.

Your JetBlue Mosaic status begins when you meet the criteria and is valid for the rest of that calendar year and the entirety of the following year. So, if you reach the status requirements in June 2025, you will hold the status through Dec. 31, 2026, giving you a year and a half to benefit from the perks.

Related: A business-class boost: Reviewing JetBlue’s Mint Suite

JetBlue Mosaic status tiers

TrueBlue is free to join, and all members start at the “basic” level. While the program initially offered a single status tier, this changed in 2023 when JetBlue overhauled TrueBlue and Mosaic.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

The four published tiers of JetBlue elite status are:

- Mosaic 1

- Mosaic 2

- Mosaic 3

- Mosaic 4

The differences among the tiers are based on the amount you fly and spend with JetBlue. As you fly more with JetBlue and/or utilize a cobranded credit card (among other activities), you can move up in the program.

Mosaic 1 is very similar to the former stand-alone Mosaic status. With each higher tier reached, more valuable perks become available.

How to qualify for JetBlue Mosaic status

JetBlue uses a metric known as Tiles for Mosaic status qualification purposes. Tiles can be earned in one of two ways: through qualifying spending on JetBlue flights and vacations, or with JetBlue credit cards.

You earn one Tile for every:

This means you can reach JetBlue Mosaic status entirely through credit card spending, spending with JetBlue or with some combination of the two.

Here’s what you’ll need to qualify for each Mosaic tier:

| Status tier | Tiles needed | Status earned exclusively by JetBlue travel spending |

Status earned exclusively by JetBlue credit card spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mosaic 1 | 50 | $5,000 | $50,000 |

| Mosaic 2 | 100 | $10,000 | $100,000 |

| Mosaic 3 | 150 | $15,000 | $150,000 |

| Mosaic 4 | 250 | $25,000 | $250,000 |

As you can see, earning status solely through credit card spending isn’t feasible for most travelers. It’s often easiest to use a combination of the two methods — for example:

- $3,000 in JetBlue flights (30 Tiles) plus $20,000 in card spending (20 tiles) gets you Mosaic 1 status.

- $5,000 in JetBlue flights (50 Tiles), $3,000 in Paisly purchases (30 Tiles) and $20,000 in card spending (20 Tiles) gets you Mosaic 2 status.

JetBlue Mosaic status benefits

Basic members earn 3 TrueBlue points per dollar spent on JetBlue flights (except Blue Basic fares, which earn 1 point per dollar), plus an additional 3 points per dollar when they book on JetBlue’s website (1 point per dollar for Blue Basic).

While working their way to Mosaic 1, basic members enjoy “Perks You Pick” — a selection of benefits you can choose from when you earn 10, 20, 30 and then 40 Tiles. These options include:

- Early boarding with Group B (except on Blue Basic fares)

- Priority security (where available)

- Free inflight alcoholic drink (one drink per flight)

- Double bonus points on a JetBlue Vacations package (one-time use only)

- 5,000 TrueBlue bonus points

Note that these are one-time selections, so you can’t (for example) pick 5,000 points at all four thresholds.

Then, once you hit 50 Tiles, you’ve officially earned JetBlue Mosaic status.

Mosaic 1 status

This is the lowest elite tier in JetBlue’s program, where you will receive:

- 3 bonus points per dollar spent on JetBlue flights

- Priority security and boarding

- First two checked bags free

- Complimentary beer, wine, and liquor (up to three drinks per Mosaic member per flight)

- Even More Space seats at check-in at no extra cost

- Same-day switches with no fee or fare difference

- Preferred core seating (excludes Blue Basic starting March 1)

- Dedicated check-in lines and phone support

- Heathrow Express upgrades (pending availability)

- Avis Preferred Plus status match

Mosaic 2 status

You’ll receive all of the same perks as Mosaic 1, as well as:

- Select Even More Space seats at booking at no extra cost

- Status match to Avis President’s Club

Mosaic 3 status

When you elevate your JetBlue elite status further, you unlock these benefits:

Mosaic 4 status

At TrueBlue’s top tier, you will receive everything mentioned above, as well as:

- Two additional Move to Mint certificates (pending availability), plus two more certificates for every additional 100 Tiles earned after reaching Mosaic 4 (starting in January)

- Gift Mosaic 1 status to a TrueBlue member of your choice (these members don’t receive a Perks You Pick selection)

- Dedicated Mosaic 4 phone support

However, the benefits continue beyond there. Once you reach Mosaic 1, and each time you level up through JetBlue elite status, you can choose an additional perk from the Perks You Pick menu, which includes:

- Complimentary FoundersCard Blue membership

- Pet-fee waiver

- $99 one-time statement credit for JetBlue Plus or Business cards

- 20-Tile bonus for yourself or a giftee

- 15,000 TrueBlue bonus points

- Mint Suite priority access to select the best seats (pending availability)

- IHG One Rewards Platinum Elite status

Can a credit card help earn JetBlue status?

JetBlue has three credit cards, all issued by Barclays:

| Card | Best for | Sign-up bonus | Earning rate | Annual fee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JetBlue Plus Card | Frequent JetBlue flyers | Earn 50,000 bonus points after spending $1,000 on purchases and paying the annual fee in full, both within the first 90 days |

|

$99 |

| JetBlue Card | Casual JetBlue flyers | Earn 10,000 bonus points after spending $1,000 on qualifying purchases within the first 90 days |

|

$0 |

| JetBlue Business Card | Small-business owners | Earn up to 60,000 bonus points: 50,000 points after spending $4,000 on qualifying purchases in the first 90 days and 10,000 points when a purchase is made on an employee card in the first 90 days |

|

$99 |

The information for the JetBlue Plus Card, JetBlue Card and JetBlue Business Card has been collected independently by The Points Guy. The card details on this page have not been reviewed or provided by the card issuer.

You’ll earn 1 Tile toward Mosaic status with every $1,000 spent on any JetBlue credit card, with no limit. This means you can, in theory, earn JetBlue elite status without ever stepping on a plane.

But this would require a lot of spending, and don’t forget the opportunity cost. You may get more value by putting your expenses on a card that earns transferable points on dining, travel or other popular categories. Due to their expansive lists of transfer partners, these transferable currencies are generally more valuable than JetBlue points. Plus, you can transfer Chase Ultimate Rewards points and Citi ThankYou Rewards points to JetBlue at a 1:1 ratio. American Express Membership Rewards points transfer to JetBlue at a 1:0.8 ratio.

Is JetBlue Mosaic status worth it?

If you earn Mosaic status anytime in 2025, your status lasts until Dec. 31, 2026. The earlier you achieve status, the longer you can enjoy it.

However, the Mosaic perks outlined above will only be helpful if you fly JetBlue regularly while your status is valid. There’s little benefit in focusing time and money on earning Mosaic elite status if you can’t enjoy the benefits.

If you value time-saving perks like priority boarding and security plus the money-saving benefits of free seat selection, checked bags and upgrade certificates, Mosaic elite status could be very valuable. However, the top perks require a lot of spending to earn, so be sure it’s worth that investment.

Another thing to consider is whether or not JetBlue’s route network matches your flying preferences. Mosaic elite status could be beneficial if your home airport is a JetBlue hub, such as Fort Lauderdale, Boston or New York. It may be less beneficial if your plans involve mostly international travel, since JetBlue has a limited international network (primarily in the Caribbean, Latin America and Europe).

A third factor determining if JetBlue Mosaic’s status is worth it is how much you value TrueBlue points. JetBlue prices award tickets based on the cost of a paid ticket, and TPG’s January 2025 valuations peg TrueBlue points at 1.3 cents apiece. However, this redemption value is generally lower when you redeem points for JetBlue Mint tickets. Since you’ll be collecting TrueBlue points on your pathway to earning status, ensure they unlock the rewards you want.

Finally, consider the perks that are important to you. You may be able to get these by simply adding a JetBlue credit card to your wallet, rather than going out of your way to earn Mosaic status. For example, the JetBlue Plus Card includes a free checked bag for you and three companions, 5,000 points on your cardmember anniversary, 50% off eligible inflight purchases, and 10% of your TrueBlue points back as a rebate when you book JetBlue-operated award flights. This may be plenty for a casual JetBlue flyer.

Bottom line

Earning elite status on any airline is a marathon, not a sprint, requiring loyalty throughout the year. However, JetBlue provides some flexibility in that you can reach Mosaic status through a combination of flying and credit card spending.

With perks such as complimentary Even More Space seat selection, Mint upgrades and priority service, the rewards for your loyalty to JetBlue can be very worthwhile. This is especially true for those who live in cities with a significant JetBlue presence, especially with Mint service (JetBlue’s award-winning business class).

Travel

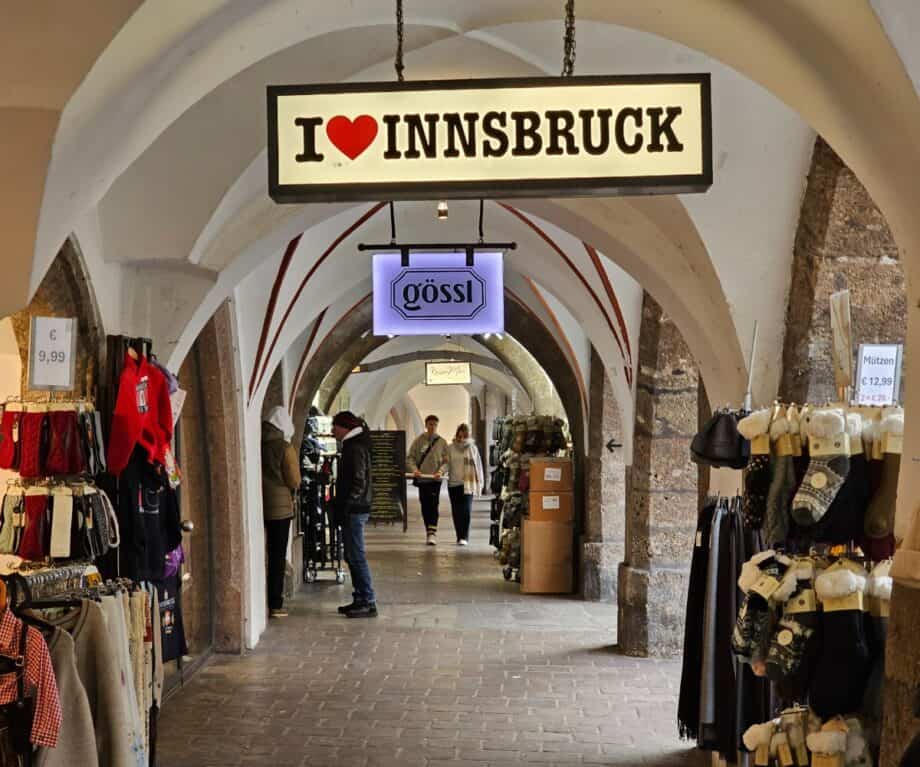

First time in Innsbruck? Discover the city with a private guided tour

The first thing that struck us as we disembarked our flight at Innsbruck Airport — other than the fresh, bracing air—was the breathtaking mountain scenery encircling us. Towering, snow-dusted peaks are all around, glowing in the morning sunlight – a natural amphitheatre promising several days of history, fun and adventure.

The second thing that stood out was the remarkable ease of travelling from the airport to the heart of Innsbruck. Few international airports in Europe allow you to be dining in a restaurant in the city centre within an hour of landing, but in Innsbruck it’s possible to achieve this effortlessly. Once through passport control and the baggage claim area, the F bus immediately outside the airport doors swiftly connects you to Innsbruck Hauptbahnhof (the main train station from which you can easily explore the Old Town on foot) in just 15–20 minutes.

And so, we did just that, stopping at Weisses Rössl for a wonderful Tyrolean lunch. But for first-time visitors to the city, I’d strongly recommend taking a private guided tour. It’s a great way to immerse yourself in Innsbruck’s rich history, culture and hidden gems that might otherwise go unnoticed. Our certified Austria guide, Monika, greeted us with a warm smile and the promise of unique insights — stories and details that only someone with centuries of family roots in the city could share.

We set off to explore the city’s layers of history, noting that the streets are dotted with intricately wrought-iron signs. These ornate markers, each a miniature work of art, once served as advertisements for the city’s merchants. From gilded boots to gleaming scales, these signs were not merely decorative but also practical, helping visitors and locals to navigate Innsbruck’s winding streets before literacy was widespread.

We are led to the nearest bridge where we pause to take in a view that perfectly encapsulates Innsbruck: the River Inn, flanked by the pastel façades of Mariahilfstrasse. Each building was painted a different colour—a tradition that began as a way to identify homes and shops but has also become a symbol of the city’s vibrant personality.

Here, Monika drew our attention to the river’s formidable presence. In Spring, the snowmelt floods its banks, often threatening to breach the bridges that connect the city. It’s a reminder of how closely life here is intertwined with nature and the surrounding landscape.

The marketplace near the bridge is alive with energy each morning – it’s a thriving hub of farmers and vendors selling everything from ripe produce to Alpine cheeses, something which the locals take an immense pride in.

Innsbruck’s history unfolded as we entered the Old Town. Monika led us to the Golden Roof, the world-famous symbol of the city with its 2,657 fire-gilded tiles. Built by Emperor Maximilian I, the roof was a symbol of his power and influence when Innsbruck was the capital of Europe.

Maximilian’s legacy looms large here and there’s a plaque that lists notable visitors to the city, including the likes of Napoleon Bonaparte and Empress Maria Theresa,he mother of Marie Antoinette.

Through strategic marriages, Maximilian expanded his empire across the continent, earning the title of Europe’s last knight. But even an emperor’s resources are finite. When his ambitious projects drained his treasury, he left Innsbruck for Vienna, where he died. He’s not buried in the city he so adored, but statues of significant historical figures, particularly from the Habsburg dynasty – which had been built to surround the tomb of Emperor Maximilian I – remain in the Hofkirche.

These statues are a marvel of Renaissance craftsmanship, each figure etched with exquisite detail. Monika pointed out one particularly fascinating statue, which cleverly depicts the artist’s self-portrait in the elbow. Preserved in Innsbruck, these statues survived the bombing of Vienna during World War II, and a poignant reminder of the city’s role as a guardian of history.

Nearby, Dom St. Jakob’s painted ceiling is an exquisite work of art. What appears to be a grand dome is, in fact, a flat ceiling – a masterpiece of illusion, painted to create depth where none exists.

Innsbruck’s spirit of resilience came alive again as Monika recounted the fire that once ravaged the city. From its ashes rose the domed walkways that now characterise the Old Town, offering shelter from weather and a demonstration of the city’s ability to adapt and endure. This theme of survival is mirrored in its people – as Monika noted, those born in Innsbruck often stay or, if they leave, feel an irresistible pull to return. There’s something magnetic about life here, a harmony that blends tradition with progress.

That progress is evident in the youthful energy coursing through the city, thanks to its thriving university, whilst Innsbruck’s proximity to Italy and Germany adds to its vibrancy; introducing new cultures and cuisines. Yet Innsbruck itself feels complete, its charm rooted in its people and its connection to the land.

Our tour ends at Adlers Hotel, a modern counterpoint to the city’s historic heart. It has been a fascinating insight into Innsbruck and a wonderful way to begin our trip. As we say farewell, we now understand what Monika means about the pull of the place. – we’ve only been there a few hours but are already longing for more.

Disclosure: Our trip was sponsored by Innsbruck Tourism.

Did you enjoy this article?

Receive similar content direct to your inbox.

Travel

Wildfire-ravaged Los Angeles wants visitors to help the area recover and rebuild

As Los Angeles slowly begins to assess the damage caused by recent wildfires, it’s clear that rebuilding will take years and cost an astronomical sum of money. Some reports estimate a cost as high as $40 billion. Not to mention the threat of more fires remains strong as the Santa Ana winds and dry conditions persist. The possibility of rain showers this weekend offers hope that the worst of the fires could be over — though the rain could bring new challenges to the area.

In response to the devastation and lingering conditions, LA Mayor Karen Bass signed an executive order on Jan. 21 ordering expedited cleanup in burn areas and mitigation of fire-related pollutants in local stormwater systems, beaches and ocean water. The order also directs the city’s department of public works crews to clear and remove vegetation, shore up hillsides with reinforced concrete barriers, lay down sandbags and clear debris from affected neighborhoods ahead of rainfall.

“With rain in the forecast, it’s imperative we take aggressive action to prevent additional damage in burn areas and to protect our water and ocean from hazardous runoff,” Bass said in a press release. “These communities have already endured unimaginable loss — we are taking action against further harm.”

The Eaton and Palisades fires have killed at least 28 people and destroyed more than 14,000 structures in Altadena and Pacific Palisades. According to the Associated Press, the Palisades fire had reached 61% containment and the Eaton fire had reached 87% as of Tuesday.

As city and county leaders begin the recovery process, tourism and hospitality officials have announced that the City of Angels wants and needs the support of visitors.

“Los Angeles has always been a beacon to the world — a place where dreams are born and stories unfold from the silver screen to iconic landmarks,” Visit California president and CEO Caroline Beteta said in a press release sent to TPG. “One of the best ways to support the comeback of Los Angeles is to plan a trip.”

Much like Maui after it suffered its own horrific wildfires, Los Angeles is hoping tourism can help kickstart its economic recovery from the calamitous event. The fires not only destroyed homes and entire neighborhoods, but local businesses as well.

“The city, along with its iconic sites and experiences — the Hollywood Sign, Universal Studios Hollywood, the Santa Monica Pier, Getty and Getty Villa, Griffith Observatory and many more — remain intact and accessible to visitors from around the world,” Beteta said. Of course, some wonder if the time is right to visit the city so soon after the destruction.

Is now the right time to visit Los Angeles?

This is a tricky question. Just as Maui struggled with balancing its all-important tourism industry and locals’ rebuilding needs, LA has to manage a similarly delicate situation.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

Obviously, the areas most affected by the fires, like Pacific Palisades, should be off-limits to visitors. Many residents are still unable to return home to survey damage; the last thing they or first responders need is intrusive tourists trying to get a close-up look. The air quality remains poor in some parts of LA, so that’s also something to consider before booking a trip.

However, many shops and restaurants have reopened in popular areas such as Beverly Hills, Santa Monica and West Hollywood. To highlight the urgency of keeping tourism alive and aiding recovery efforts, city hotel and tourism officials put out a call to action on Jan. 21 urging visitors to not cancel their travel plans.

According to their statement in a press release sent to TPG, more than 540,000 people work in the LA tourism industry in some capacity, and a significant number of those employees were likely affected in some way by the wildfires. The influx of visitors and the money they spend helps them get back on their feet.

To give you an idea of just how important tourism is to the city’s bottom line, nearly 50 million people visited Los Angeles in 2023, contributing more than $40 billion in sales to the local economy along the way. Additionally, visitors in 2023 contributed $312 million in Transient Occupancy Tax revenue from their hotel stays.

What’s open in Los Angeles?

As we mentioned earlier, many of the city’s most popular attractions have already reopened. Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures have both resumed studio tours on their Hollywood lots. Major theme parks like Disneyland, Universal Studios Hollywood and Knott’s Berry Farm have all resumed operations, as have the world-renowned Griffith Observatory and Griffith Park (in view of the iconic Hollywood sign).

Most museums — including the Natural History Museum in Exposition Park, the La Brea Tar Pits, the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures — are also operational again.

Speaking of the Oscars, the film adaptation of “Wicked” just scored 10 Academy Award nominations. If you are in LA and want to see the touring production of the stage musical, it has resumed performances at the Pantages Theatre and is playing through Feb. 2.

There are still a number of attractions that have not reopened, though. The Getty Museum in Los Angeles remains closed through Jan. 27. Meanwhile, the Getty Villa — which, despite being located in Pacific Palisades, escaped major damage from the wildfires — is closed until further notice. The popular Runyon Canyon and Will Rogers State Historic parks are also closed.

How you can help Los Angeles recover

One of the easiest ways to contribute to recovery efforts as a visitor is to give the local economy a little help. Dine LA Restaurant Week is going on from Jan. 24 through Feb. 7; you can find a list of participating restaurants and make reservations here. Each reservation at one of these restaurants will benefit wildfire relief efforts coordinated by the American Red Cross.

Another easy way to contribute is to attend one of several fundraising events occurring in the city over the next few weeks. Discover Los Angeles has an extensive list of upcoming relief efforts on their website.

Something else that’s desperately needed? Volunteers. Some LA-based organizations that need help include:

- Habitat for Humanity LA: It needs contributions and volunteers to help wildfire survivors rebuild.

- LA Food Bank: It needs many people to help the local food bank feed some of the thousands of people affected by the fires.

- LA Animal Services: It needs foster pet parents to help with the number of dogs and cats who have ended up in local shelters since the start of the fires.

More volunteer resources are available on the city’s official website.

We’ll keep this story updated as we get more information.

Travel

First look at Universal Orlando’s new Stella Nova Resort near Epic Universe

It’s no secret that 2025 is going to be an “epic” year for Universal Orlando Resort. The resort’s third park, Universal Epic Universe, is scheduled to open on May 22. But you don’t have to wait until then to explore some of the park’s other exciting new developments.

In addition to Epic Universe, Universal is opening three new hotels and adding 2,000 guest rooms to its portfolio this year. The first of these, Universal Stella Nova Resort, opened on Jan. 21, 2025, and TPG was among the first to stay at this galactically cool property.

The hotel’s design is inspired by the vast and beautiful wonders of outer space, which you can see reflected throughout the property starting with the exterior. The facade of the hotel is covered by more than 140,000 colorful dichroic tiles that change color based on the lighting and time of day. When I arrived around midday, they were shimmering in an entire rainbow of hues, but in the evening they take on darker blues and purples.

Upon entering the lobby, you’ll see space-themed artwork inspired by NASA photographs. The cosmic aura continues through to the nebulalike purple, blue and white color scheme and the spaceport windows in the guest rooms.

Here’s a first look at Universal Stella Nova Resort, including cost, amenities, dining and theme park perks.

What does it cost to stay at Stella Nova Resort?

Stella Nova Resort is part of Universal’s Prime Value lodging category (Universal Aventura Hotel and the soon-to-open Universal Terra Luna Resort also belong to this collection).

Prices start at $147 per night (plus tax), but this price is only available for stays of four nights or longer. On average, we found pricing to be closer to $200 to $230 per night for a one-night stay. Every room at Stella Nova is a standard two-queen room, so the only price difference you will find is if you choose a pool-view room over a standard view. You’ll pay between $10 and $20 more for a pool view.

The parking cost for overnight guests is $30 plus tax per vehicle per night.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

Stella Nova Resort is bookable via the Capital One Travel portal. Eligible Capital One cardholders can book this resort via Capital One Travel and pay in cash with their Capital One card or redeem Capital One miles. When you pay using your card, you can earn up to 10 miles per dollar spent, depending on the Capital One card you carry.

Among the Capital One cards you should consider using if booking this way are:

Stella Nova Resort location

Stella Nova, along with Universal’s other two upcoming hotels, is located adjacent to Epic Universe. Epic Universe itself is about three miles from the rest of Universal Orlando, but there is a complimentary shuttle service between the new park (and its hotels) and the rest of Universal Orlando Resort. From Stella Nova, it is about a 12-minute bus ride to Universal Orlando’s main security area that leads to Universal Studios, Islands of Adventure and CityWalk (bus transfer is available to Volcano Bay water park).

From Orlando International Airport (MCO), it’s about a 20-minute drive to Stella Nova Resort. Universal does offer a paid shuttle service called the SuperstarStar Shuttle, but ride-hailing services and rental cars are also readily available.

Inside Stella Nova Resort guest rooms

1 of 2

TARAH CHIEFFI/THE POINTS GUY

All 750 rooms at Stella Nova Resort are double queen rooms that sleep up to four guests, so the layouts are similar in every guest room, though you can choose from standard-view and pool-view categories. ADA-compliant rooms are available. A standard-view room looks over the back of Epic Universe. You can see portions of the park peeking out, which builds the excitement for your vacation.

1 of 5

Universal Stella Nova Resort. TARAH CHIEFFI/THE POINTS GUY

Inside the rooms, the color scheme is similar to that of the hotel’s public areas, with space-inspired art. A few fun details, like a galactic mural behind the beds, Creamsicle-colored accent pillows and sleek, curved furnishings add to the futuristic feel.

The beds are soft and comfortable, with a thin coverlet that isn’t necessarily a bad thing when you consider the typical outside temperatures in Orlando. I also appreciated that there was a QR code on the TV that I could scan to use my phone as a remote control (there is a standard remote, as well).

1 of 4

Universal Stella Nova Resort. TARAH CHIEFFI/THE POINTS GUY

Similar to many other Universal Orlando hotels, the bathroom is split-style, with a sink and vanity in the center and a door that separates it from the toilet and tub. This not only allows for privacy but also makes it easier for multiple guests to get ready simultaneously.

The specialty Cosmic Ember bath products had a fresh scent, and I loved the continuity of the branding even for the shampoo, conditioner and soap.

Guest rooms are also equipped with standard amenities like a coffee and tea maker, mini refrigerator, hair dryer and iron. Standard Wi-Fi is complimentary, or you can upgrade to premium Wi-Fi for $9.95 per day.

Stella Nova Resort amenities

Stella Nova offers similar amenities to Universal’s other Prime Value properties. It has a resort-style pool complex with a 10,000-square-foot pool, a hot tub, a kid’s splash pad and lawn games like hula hoops and table tennis. The resort shows poolside movies on select nights (check at the front desk for a weekly schedule).

1 of 3

Universal Stella Nova Resort. TARAH CHIEFFI/THE POINTS GUY

The hotel also has a 24-hour fitness center, an arcade, laundry facilities, an Avis car rental desk, a ticket desk to assist with theme park planning needs and a gift shop so special (for now, at least) that it is one of the first hotels to feature a large collection of Epic Universe merchandise. I saw shirts, toys and collectibles representing all of the lands coming to the new park and some general Epic Universe-branded merchandise.

1 of 5

Universal Stella Nova Resort. TARAH CHIEFFI/THE POINTS GUY

Universal Creative turned an unused portion of the third floor with no guest rooms into a “sky bridge” with starry lights in the ceiling, which is already proving to be a popular spot after being open only a couple of days.

If you can’t resist getting that perfect Instagram photo in this trippy space, try to do so quietly so as not to disturb the guests staying on this floor.

Stella Nova Resort dining

Stella Nova Resort has several dining options to keep you fueled up for your theme park adventures.

Cosmos Cafe and Market

Located in the hotel lobby, Cosmos Cafe and Market is a quick-service outlet that serves breakfast, lunch and dinner daily. It also offers a selection of grab-and-go items like ice cream, snacks, prepackaged salads and sandwiches and coffee drinks.

The menu is comprised mostly of American classics like burgers, fries, pizza and pasta, but there are some specialty items as well. I stopped by for lunch during my stay (which was too brief to make time for breakfast).

I tried the hot honey pizza ($15.50), which was topped with cheese, garlic cream sauce, buffalo chicken and, of course, hot honey. It was tasty — and spicy. I had the Mexican street corn ($7) on the side, which was by far my favorite dish and a huge portion for being a side item. My dining companion had the Stella burger ($15.50), which was a delicious classic burger.

All in all, the food was good and filling, but there are so many good dining options inside the park and at CityWalk, I think I would save my Stella Nova meals for when I needed something before heading out for the day or when I was starving after a long day at the parks.

Nova Bar

Nova Bar is also located in the lobby and is open daily from 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. In addition to classic beer, wine and cocktails, you’ll find space-themed drinks like the Black Hole ($16), which is basically an espresso martini, and the Super Nova (also $16), a whiskey-based cocktail with cherry-infused Campari and tart cherry syrup served smoked over a large ice cube.

Galaxy Bar and Galaxy Grill

Galaxy Bar and Galaxy Grill are the hotel’s poolside drink and dining options. Starters include things like chips and salsa, hummus and veggies and a Mexican shrimp cocktail. For your meal, you can choose from a selection of salads, burgers, sandwiches and wraps.

Galaxy Bar has a lengthy beer list with a mix of cans and drafts and a handful of hard ciders and seltzers.

Pizza delivery

Direct-to-room pizza delivery is also available daily between 5 p.m. and midnight. You can place your order via phone or the online order form.

Stella Nova Resort theme park perks

Like all Universal Orlando hotels, guests enjoy certain perks that only onsite hotel guests enjoy. These include early access to select theme parks and attractions each morning. Which park(s) and attractions you get access to can vary by day, but you’ll get a 30-minute head start at Volcano Bay and a full hour at Islands of Adventure or Universal Studios.

Stella Nova guests also get park-to-hotel package delivery, resort-wide charging privileges using their room key and complimentary shuttle service to and from Universal’s theme parks and CityWalk. Even if you drive, I recommend using the shuttle service because Universal does not offer free theme park parking to hotel guests.

Stella Nova (like its sister property, Terra Luna) has a walking path that will lead to Epic Universe when the park opens in May. It’s about a 10-minute walk, but you can also take the shuttle if you choose.

Things I loved about Stella Nova Resort

- I am a sucker for good theming, so I was all-in on the chic spaceship vibes Stella Nova was giving off. Everything from the futuristic lobby seating to the artwork felt upscale and ultramodern. With theme parks leaning more and more toward immersing guests in the worlds they create, it only makes sense that Universal would extend this sentiment to its hotels.

- The excitement for Epic Universe’s grand opening this year is palpable among theme park fans. Stella Nova offers the first and only way for Universal guests to stay so close to this groundbreaking new park and get a glimpse inside even while they are still putting the finishing touches on the attractions. Aside from adding to the anticipation, once the park does open, guests staying at Stella Nova Resort will be only a short walk or bus ride away from Epic Universe.

- Especially while everything in the hotel is shiny and new, you cannot beat this resort’s level of theming and amenities at such an affordable price point. Universal has hotel rooms that range from the $150 range all the way up to as much as $800 per night. Obviously, you get what you pay for, and Stella Nova appears to be a great value for the nightly rate.

Things to consider before staying at Stella Nova Resort

- Though you are a stone’s throw from Epic Universe when you stay at Stella Nova, you are a few miles away from the rest of Universal Orlando Resort. If you prefer the convenience of taking a boat, bus or short walk to Universal Studios, Islands of Adventure and CityWalk, that will not be an option when you stay here.

- Unlike Universal’s Signature Collection properties (like the upcoming Universal Helios Grand Hotel), you won’t find amenities like multiple pools, waterslides, formal sit-down dining, 24-hour room service or luggage delivery. If those are luxuries you are acclimated to, you need to consider whether you can do without them at Stella Nova.

Bottom line

Universal Stella Nova Resort is the first of three new hotels opening near Epic Universe this year and it sets a high bar. Universal Terra Luna Resort opens on March 25, 2025, and should be similar in all but its theming, while Universal Helios Grand Hotel will become Epic Universe’s flagship hotel when it opens along with the new park on May 22, 2025.

The reasons for staying at this particular hotel will be obvious once the park opens, but it offers a rare opportunity to be among the first guests on Epic Universe property for those who choose to stay here now even before May. I can confidently say I was not ready to come back down to Earth after my out-of-this-world visit to Universal Stella Nova Resort.

Related reading:

Travel

New Chase bonus spending offers and a chance to earn a $100 statement credit

Jan. 23, 2025

•

3 min read

New Chase bonus spending offers and a chance to earn a $100 statement credit

Chase is back with another targeted promotion: Eligible Chase cardholders can earn 5 or 7 bonus Chase Ultimate Rewards points per dollar spent on groceries, gas and dining purchases made with select credit cards.

This promotion targets more than 25 credit cards. Ultimate Rewards earning potential varies based on credit card but applies to purchases of up to $1,000 made between Jan. 15 and March 31.

Below are some of the credit cards with this targeted promotion:

To participate in this promotion, log into your Chase account to see if you are targeted. Eligible cardholders can earn 5 or 7 bonus points for each dollar spent on grocery, gas and dining purchases (on up to $1,000 in purchases) for transactions from Jan. 15 until March 31 at 11:59 p.m. EST. After activating the offer, select cardholders will receive a $100 travel credit for bookings of at least $400 made by Jan. 31 and for travel by Aug. 31.

Other credit cards — including the Aer Lingus Visa Signature® Card, the Iberia Visa Signature® Card and the Disney® Premier Visa® Card — are eligible for this promotion, so be sure to check your Chase account to see if you’ve been targeted.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

The information for the Aer Lingus Visa Signature and Iberia Visa Signature cards has been collected independently by The Points Guy. The card details on this page have not been reviewed or provided by the card issuer.

You can stack this offer with the previously announced offer in December that gives Targeted Chase cardholders the chance to earn 10,000 bonus points through the Chase Travel℠ portal. Note that your hotel stay must total at least $400 in a single transaction, and you must book travel by Jan. 31 for trips completed by Aug. 31.

Featured image by ANDRESR/GETTY IMAGES

Editorial disclaimer: Opinions expressed here are the author’s alone, not those of any bank, credit card issuer, airline or hotel chain, and have not been reviewed, approved or otherwise endorsed by any of these entities.

Travel

Travel warning: Holidaymakers issued urgent guidance as Ireland braces for ‘severe’ weather

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) has issued an urgent travel warning for British citizens planning to visit Ireland as Storm Éowyn approaches.

The warning comes as extreme weather conditions are expected to impact the country over the next two days.

The FCDO stated: “There are severe weather warnings in place for Ireland for January 23 and January 24 January due to Storm Éowyn.”

The warning covers the entirety of today and tomorrow, with Irish weather services providing detailed forecasts of the storm’s impact.

‘There are severe weather warnings in place for Ireland for January 23 and January 24’

GETTY IMAGES

The FCDO advised British travellers to check their travel plans in advance before heading to Ireland during the severe weather period.

They should also monitor Ireland’s weather service for the latest updates on Storm Éowyn. Visitors were also instructed to “follow the advice of local authorities”.

The Irish Meteorological Service has updated its weather warnings, issuing Red warnings for several parts of the Ireland and Northern Ireland. Orange and yellow warnings have also been issued for other parts.

Travellers should keep up-to-date with warnings for their specific destination in Ireland.

A ‘Red’ Wind warning for Carlow, Kilkenny, Wexford, Cork, Kerry, Limerick and Waterford reads: “Gale to storm force southerly winds becoming westerly with extreme, damaging and destructive gusts in excess of 130km/h.”

The warning is valid from 2am – 10am on Friday, January 24.

Potential impacts include:

- Danger to life

- Extremely dangerous travelling conditions

- Unsafe working conditions

- Disruption and cancellations to transport

- Many fallen trees

- Significant and widespread power outages

- Impacts to communications networks

- Cancellation of event

- Structural damage

- Wave overtopping

- Coastal flooding in low-lying and exposed areas

Red warnings issued in Ireland

- Wind warning for Carlow, Kilkenny, Wexford, Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Waterford

- Wind warning for Clare, Galway

- Wind warning for Leitrim, Mayo, Sligo

- Wind warning for Cavan, Monaghan, Dublin, Kildare, Laois, Longford, Louth, Meath, Offaly, Westmeath, Wicklow, Roscommon, Tipperary

- Wind warning for Donegal

Red warnings issued in Northern Ireland

- Wind Warning for Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Derry

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS

Holidaymakers should be aware of ‘extremely dangerous travelling conditions’

GETTY IMAGES

Each warning details the potential impact of Storm Éowyn and how long the warning is valid.

The Met Office stated: “Red Warnings for wind have been issued for Northern Ireland as well as central and southwestern areas of Scotland on Friday. These are accompanied by wider Amber and Yellow Warnings for wind, as well as Yellow Warnings for rain and snow.”

Before going abroad, it is always advisable to consult the FCDO’s latest guidance for your chosen destination for a safe, well-informed trip.

This will include the latest information on warnings and insurance, entry requirements, any regional risks, safety and security, health and getting help.

Britons were recently issued a travel warning as an Asian tourism hotspot faces “heightened tensions”.

Travel

All-new rooms and a Netflix restaurant are coming to the MGM Grand Las Vegas

Last year, MGM Resorts International and Marriott finalized a deal that saw an impressive collection of Las Vegas megaresorts join the Marriott Bonvoy family. Now, the gaming giant’s namesake property, MGM Grand, is unveiling an extensive renovation set to uplift the resort by $300 million.

Related: Marriott Bonvoy and MGM Resorts boost loyalty partnership benefits for 2025

Scheduled for completion by December, the planned $300 million face-lift will give the main tower’s 4,212 rooms and suites a new life with a modern take on “the flair of the disco era,” according to a statement from MGM Resorts International.

Designed in partnership with architecture firm Gensler and MGM Resorts Design & Development, the updated rooms will have warm gray wall coverings, updated media consoles, updated outlets near beds, modern smart TVs, enhanced blackout drapery, more surface space, new refrigerators that are separate from the minibar, and updated spa-inspired bathrooms with new walk-in showers.

The remodel will also add 111 suites to the hotel’s inventory, bringing the total number of suites up to 753, starting at 675 square feet in size and maxing out at over 2,500. The new and upgraded suites will have strong dark finishes with lighter accents like sheer roller shades to bring in light. Living areas will include new sections and artwork that transforms based on your vantage point. Overall, the suites will be more functional, with layouts that more clearly divide work from entertainment.

The new rooms and suites will be available to book starting March 1.

Daily Newsletter

Reward your inbox with the TPG Daily newsletter

Join over 700,000 readers for breaking news, in-depth guides and exclusive deals from TPG’s experts

New dining and entertainment experiences

Though rooms and suites are the main focus of this project, other areas of the resort are also getting some exciting changes.

Starting Feb. 20, MGM Grand will be home to an experiential full-service restaurant called Netflix Bites, created in partnership with streaming service Netflix. Found on the casino floor, Netflix Bites will be open for breakfast, lunch and dinner and serve a menu inspired by hit Netflix shows like “Stranger Things,” “Bridgerton” and more.

A teaser of the menu includes:

- “Eleven’s Fried Feast” — crispy chicken and waffle sliders perfect for foodies who love a little dimension-hopping, served both “Hawkins” style and “Upside Down”

- “Bridgerton Regency Tea” — a lavish three-tiered tea service with finger sandwiches, scones and pastries straight from the Ton, served with a menu designed by Lady Whistledown herself

- “La Casa del Sangria” — a Spanish-style cocktail with gold-dusted mint leaves, served in a lockbox that’ll have guests solving a puzzle, challenging for even the sharpest of the “Money Heist” crew

- “Too Hot to Handle”-inspired bloody mary — a cocktail so spicy it comes with its own potholder in case guests can’t handle the heat

MGM Grand will also be home to a new day club called Palm Tree Beach Club, set to open in May. Founded by musical artists Kygo and Myles Shear, the day club will open in partnership with Tao Group Hospitality, known for its collection of famous resorts around the world.

Once open, the Rockwell Group-designed club will span 60,000 feet and have a stage, a saltwater pool, bungalows, cabanas, daybeds and chaise lounges in a space designed to fit more than 3,000 people.

Related reading:

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years agoThese ’90s fashion trends are making a comeback in 2025

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe Season 9 ‘ Game of Thrones’ is here.

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago9 spring/summer 2025 fashion trends to know for next season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe old and New Edition cast comes together to perform You’re Not My Kind of Girl.

-

Sports8 years ago

Sports8 years agoEthical Hacker: “I’ll Show You Why Google Has Just Shut Down Their Quantum Chip”

-

Business8 years ago

Uber and Lyft are finally available in all of New York State

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Disney’s live-action Aladdin finally finds its stars

-

Sports8 years ago

Steph Curry finally got the contract he deserves from the Warriors

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Mod turns ‘Counter-Strike’ into a ‘Tekken’ clone with fighting chickens

-

Fashion8 years ago

Your comprehensive guide to this fall’s biggest trends

You must be logged in to post a comment Login