What we used to think of as Britain’s two main parties, Labour and the Conservatives, seem more than happy to postpone as many of this year’s upcoming local elections as possible.

Labour insists the delays are needed because of ongoing local authority reorganisation. Opponents allege the decision has more to do with opinion polls that show both parties losing out badly to Reform, the Lib Dems and the Greens.

Who knows which is true? But it’s all yet another reminder that the UK’s formerly cosy, two-party system seems to be falling apart in front of our eyes.

In a year that holds the potential for electoral gains in councils and in races for the Welsh Senedd and Scottish parliament, what we used to refer to as country’s “minor” parties will have to run many campaigns.

In order to take full advantage of that fragmentation, they ideally need boots on the ground – people prepared to knock on doors and push leaflets through letter boxes in order to encourage supporters to actually get out and vote. These days, it’s also useful to have people willing to create (or at least share) content online.

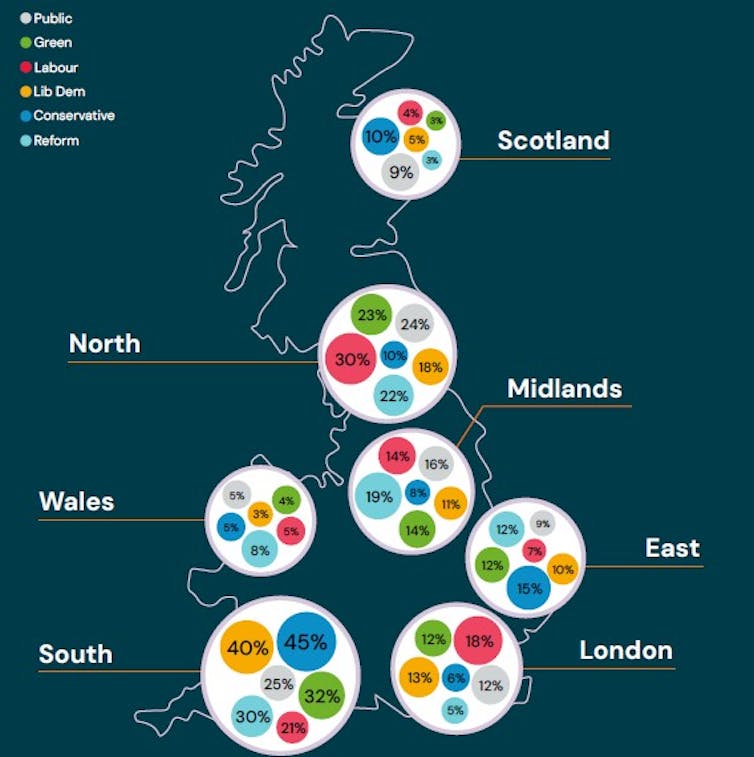

That raises the question: who do they have? Given that the people who do the most campaigning for parties are its members, we can start by looking at how these numbers are distributed around the country. Reform makes big splashes in the national media, but does it have people who know the ground in the Vale of Clwyd?

My colleagues and I – the party members project run out of Queen Mary University of London and the University of Sussex – have looked into this in a newly published report.

It’s one thing to have plenty of party members – and there have been huge surges in people joining both the Greens and Reform since we conducted our surveys around the time of the 2024 election – but it matters where they’re located and how much they’re prepared to do.

Obviously, it helps to have members in those areas of the country that, opinion polls suggest, are particularly fertile territory. This may well be the case for the Lib Dems and for Reform, although Reform leader Nigel Farage will surely be hoping that that he’s managed to recruit a few more members in Wales and in London since we did our field work.

At that time, just 8% of Reform members were located in Wales, compared to 30% in the south of England. Only 12% of members were in London, where every borough has a council election in 2026.

T Bale, CC BY-ND

As for the Greens, they look rather thinly spread. Like Reform, there’s more of a presence in the south, where 32% of members are to be found. But in London it’s 12%, although it looks like that might be changing fast and for the better in some parts of the capital.

Certainly, irrespective of which region they’re located in, if Green party members live in those multicultural urban areas where Labour looks vulnerable, then they could still prove very useful in May.

How useful members are, of course, also depends on whether they’re willing to actually help out. At the 2024 election, from which our data is derived, around a third of all Lib Dem and Reform UK members, devoted no time at all to their party’s campaign efforts. The Tories, Greens and Labour had it even worse. Around half of their members put no time in.

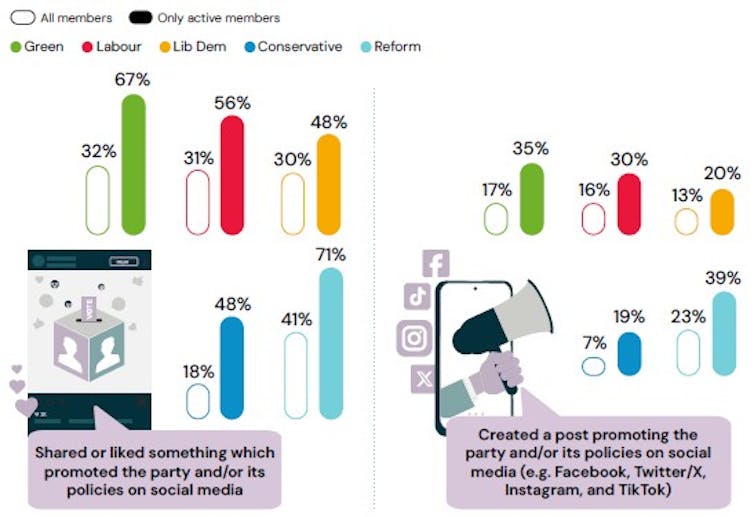

Digging a bit deeper into the kind of activities members do reveals some interesting differences. In the increasingly important online world, it looks as if the Greens and Reform UK may well have something of an advantage. Their members were more likely to share social media content about their party than members of the Lib Dems and Conservatives.

T Bale, CC BY-ND

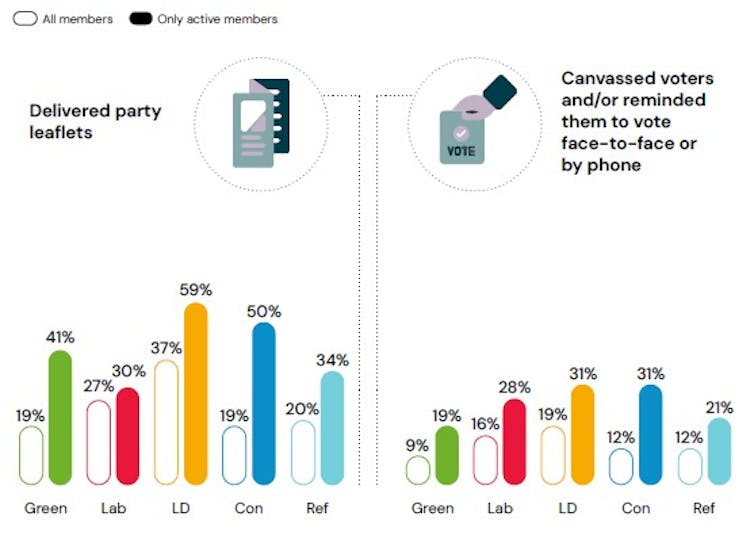

On the doorstep, however, it’s the Lib Dems who are right up there. Some 37% of Lib Dems delivered leaflets to people’s homes in 2024 – a figure that rises to 59% if we ignore those members who told us they’d done nothing for the party during the election.

This is one of the reasons, along with continued Conservative weakness, why, in spite of them being paid far less attention than current media darlings, the Greens and Reform UK, Lib Dem leader Ed Davey’s often underrated party stands to do well in the spring.

Reform’s membership performed less impressively in 2024 – only 20% delivered leaflets, albeit a figure that rises to 34% if we take those members who did nothing at all out of the equation. The figures for canvassing (a rather more demanding activity which parties often struggle to persuade members to help with) – 12% and 21% – are much lower.

T Bale, CC BY-ND

A key question for Farage, then, will be how he can motivate the people who’ve flooded into his party (boosting its membership to over 270,000) to get out on the doorstep or at least hit the phones in order to contact voters. Zack Polanski faces a similar challenge when it comes to the 150,000 people who now belong to the Greens, most of whom have joined since he took over as leader.

Campaigning by members isn’t everything, of course. Activists who aren’t members play a part, as does top-down, national campaigning – even in local elections. Still, these figures do give some insight into the strengths and weaknesses of party organisation around the country at the start of what looks set to be a crucial set of elections this spring.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.