A Christmas Carol is usually read as a Victorian morality tale about capitalism and compassion. Yet an autographed script written by Charles Dickens during the American Civil War raises the possibility he may also have understood the story as speaking to the cause of ending slavery in the US.

First published in the UK on December 19 1843, the novella is famous for its advocacy of a reformed relationship between the Victorian capitalist Scrooge and the workers whose labour he profits from, epitomised by his downtrodden clerk, Bob Cratchit. The story has inspired countless adaptations in theatre, television and film.

However, a slip of blue paper held in Harvard’s Houghton Library shows how Dickens may have also seen the story through the lens of American slavery. As my current research in the library’s collections shows, on March 7 1864, Dickens wrote out and autographed A Christmas Carol’s most famous line so that it could be sold in aid of the anti-slavery side in the ongoing American civil war (1861–65).

The closing sentence – “And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God Bless Us, Every One!” – is usually associated with Victorian families united in the Christmas snow. However, Dickens’ contribution to a set of celebrity autographs being collected for sale at the 1864 New York Metropolitan Fair enlisted his novella in the cause of supporting the Union army’s goal of ending slavery in the US.

HEW 16.3.16. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University

The New York fair was one of several events held across the Union states to raise funds for the US Sanitary Commission, a philanthropic organisation which promoted the health, welfare and convalescence of Union soldiers. We don’t know how much the autograph collection to which Dickens contributed ultimately sold for. But records show the collection, gathered by the wife of the US ambassador to Britain, Abigail Brooks Adams, was valued at US$1,000 – approximately US$20,000 (£14,500) in today’s money.

Dickens had been an international celebrity since the 1830s, and was well accustomed to requests for autographs. In 19th-century terms, this often meant a copied-out passage from one of his novels as well as a signature.

What survives of these autographs, written for fans in Britain and America, suggests that the passage he typically used was the death of Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop (1841). His unusual choice of the final line from A Christmas Carol therefore seems deliberate for this specific context.

In my ongoing research, I theorise this choice may have been designed to remind people that the message of A Christmas Carol also applied to enslaved black people in the US and show his support for them.

While there are no direct references to slavery in A Christmas Carol, there are good reasons to think it was on Dickens’s mind at the time he was writing the novella.

The two works he was publishing immediately before it – the travel book American Notes (1842) and serialised novel Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–44) – both make vivid reference to the inhumanities of slavery. They had been inspired by the five-month tour that Dickens made of the US in 1842.

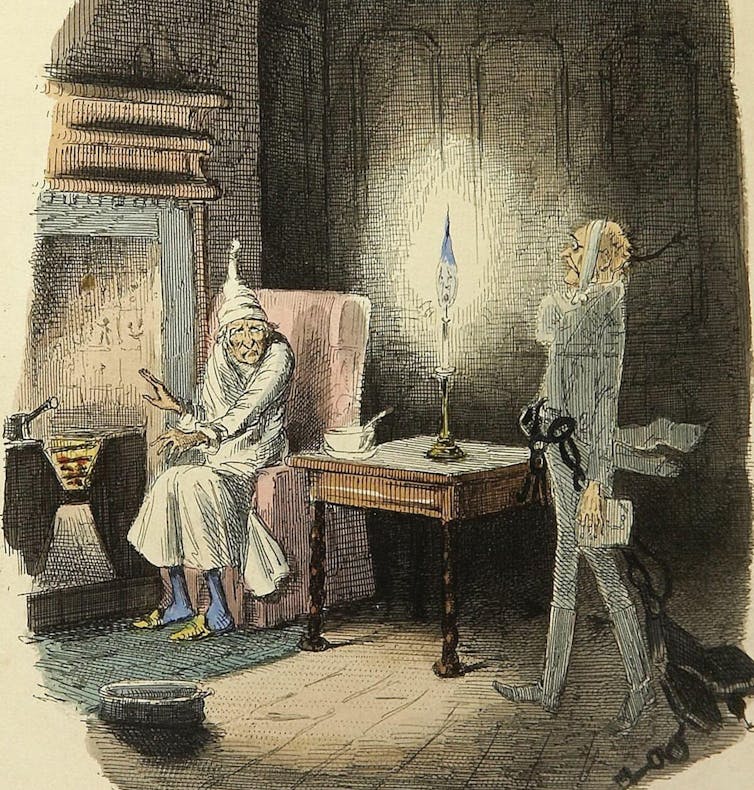

There is a long cultural history of ghosts in chains like the ones that weigh down Scrooge’s partner, Jacob Marley, in A Christmas Carol. But at the time Dickens was writing it, he also had a more immediate reference point for the image of people burdened by irons.

In American Notes’s chapter on slavery, he quotes from multiple American newspaper descriptions of escaped enslaved people loaded with iron rings, chains and weights – including a 12-year-old boy with a “chain dog-collar around his neck”.

Alamy/piemags

In A Christmas Carol, Marley attributes his chain, made of “cash-boxes … ledgers … and heavy purses”, to his heartless pursuit of business profit in life. Marley warns Scrooge that he too is a “captive, bound and double-ironed”, suggesting that exploitation for money will ultimately fetter the exploiter as well as the exploited.

Two recent adaptations of A Christmas Carol have suggested that Scrooge and Marley’s business is at least partly built on the trade in enslaved people. Jon Clinch’s 2019 novel Marley makes the link direct, while Steven Knight’s television series of the same year implies it.

For example, Stephen Graham’s Marley tells Guy Pearce’s Scrooge: “Look at these chains Ebenezer … Each link is a man or woman or child who died in our workshops”, mentioning locations not only in “London, Birmingham, Manchester”, but also “Batavia … Mauritius, the Bay of Honduras”. Slavery was present in the last three locations until at least the 1830s.

While Dickens opposed slavery, he was far from immune to racism. Notoriously, his support for the brutal British colonial response to an uprising of Jamaican plantation workers in 1865 contrasted with his career-long advocacy against the deprivations of the British working classes.

In Zadie Smith’s historical novel The Fraud (2023), the character of Dickens suggests that Brits should be turning their attention from the compensation given by the British government to slave owners in the British Empire to problems closer to home. Such a portrayal is supported by Dickens’s mockery of Mrs Jellyby in Bleak House (1853) for her “telescopic philanthropy”, which centres on Africans in the fictional “Borrioboola-Gha” rather than the people in her immediate vicinity.

If Dickens did intend to use the final line of A Christmas Carol to support the anti-slavery cause in the American Civil War, this would allow us to rethink how he may have seen the relationship between exploitation and inhumanity at home and abroad. It suggests that, in at least some circumstances, he was able to see these causes in connection rather than competition.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.