News Beat

Meet John Walker, inventor of the match, from Stockton

John was such a learnéd man that he was known as “the Stockton Encyclopaedia”. One of his interests was chemistry, which helped his business as one of his sidelines in his shop at 59, High Street, was Walker’s Pea Crackers – explosive percussion caps for toy pistols that the young men of Stockton had discovered would make the young girls of Stockton scream if, on a dark night, you threw one behind them and it went off with a bang.

That day exactly 200 years ago, 45-year-old John was preparing the fire when, probably by accident, he rubbed a stick from his chemistry experiments against the coarse surface of the hearth and it ignited in a bright flame.

Perhaps other less agile minds would have thought that playing with fire was dangerous and put the stick safely away, but John realised he was onto something.

Until that moment, for thousands of years, humans had created fire by rubbing or hitting two items together to create a spark – in John’s day, people would have had a piece of flint that they bashed against a “fire steel” (a piece of iron shaped to fit into a hand) so that a spark jumped into a kindling box.

Or, in good weather, they used a piece of glass to focus the rays of the sun, as George Stephenson had done a few months earlier, on September 16, 1825, when he had lit Locomotion No 1 for the first time at Aycliffe Lane level crossing.

Humans had known about the potential for chemical combustion, but no one had worked out a way to make a portable compound – getting it to stick to a piece of wood had previously been beyond the greatest minds of all time.

Yet John’s combination of antimony sulphide, potassium chloride and gum had done just that. He had invented the match! Human existence would never be the same again.

This great inventor had been born on May 29, 1781, at 104 High Street (like his shop, demolished to make way for the Castlegate Shopping Centre which has itself been cleared away). He was the third of seven children of Mary and John Walker, who had a grocer’s and wine merchant’s.

He had attended Stockton Grammar School, where he had learned Latin, and at the age of 15 had become an apprentice to surgeon Dr Watson Alcock. Surgery 200 years ago was a pretty brutal business and John decided it was too gory for him. Instead, he spent time with pharmacists in York and Durham until, in 1819, he was able to open his open “chymist and druggist” shop at 59 High Street.

He rented the premises from printer Thomas Jennett, the three times mayor of Stockton, who lived next door at No 58.

From No 59, he gave away the first of his matches. He initially called them “Sulphurata Hyperoxygenata”, so he didn’t give away his chemical ingredients, although after some months he settled on the more pronounceable “Friction Lights”. It is thought that he gave them away as he was still trialling them – the head had a worrying habit of becoming detached when lit and flying off like a mini-fireball.

But John’s “day book”, or ledger, still exists, and in it on April 7, 1827, he records his first sale: “No 30: Mr Hixon. Sulphurata Hyperoxygenata Frict. 100 1s Tin case 2d”. So solicitor John Hixon had bought 100 matches for a shilling and a cylindrical tin for them to go in for a further tuppence.

The “No 30” in the entry is mysterious, particularly as the original entry seems to have been “No 36” which was crossed out. It is now believed that John had made 29 previous batches of matches which he had given away until he was content that his product was saleable.

He continued to refine his product. Initially he tried cardboard strips before settling on three inch long wooden splints. Then, sometime in 1827 or 1828, printer John Ellis working next door for Mr Jennett, pasted together for him the world’s first cardboard matchbox. To phillumenists – collectors of matchboxes – these boxes are the holy grail, but sadly none are known to survive. The phillumenists are, though, planning a three-day conference in May in Stockton, the birthplace of the match, to celebrate its 200th anniversary.

Locally, John’s matches sold like hot cakes, particularly to drivers on the Stockton & Darlington Railway, but they didn’t come to wider public attention until 1830 when they featured in the prestigious Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature and Art under the headline “Instantaneous Light Apparatus”.

It said: “Amongst the different methods invented in latter times for obtaining light instantly, ought certainly to be recorded that of Mr Walker, chemist, Stockton-upon-Tees. He supplies the purchaser with prepared matches, which are put up in tin boxes, but are not liable to change in the atmosphere, and also with a piece of fine glass-paper folded in two. Even a strong blow will not inflame the matches, because of the softness of the wood underneath, nor does rubbing upon wood or any common substance produce any effect except that of spoiling the match; but when one is pinched between the folds of the glass-paper, and suddenly drawn out, it is instantly inflamed. Mr Walker does not make them for extensive sale, but only to supply the small demand that can be made personally to him.”

This led to the miracles-on-a-stick being demonstrated by Michael Faraday, the famous physicist, during a lecture. Some sources say that Faraday visited John in Stockton, but this seems unlikely.

Despite advice, John did not patent his invention. He was a bachelor and felt he had enough money, but he wished them to be of benefit to the wider world.

The first person to benefit from them was Samuel Jones, who in 1829 patented his own “promethean match” which was a glass bead filled with acid on the end of a stick. A person broke the glass bead, either with pliers on their own teeth, which caused the acid to ignite.

Realising than John’s idea was far better, he copied it, and gave it the name Lucifer (“light-bringer” in Latin) and became the first commercial matchseller from his shop in The Strand, London.

John Walker only made matches for his Stockton customers and only for a few years.

He retired from his chemist’s shop in 1857, and sold all his paraphernalia to rival chemist William Hardcastle. As he had never married, he lived with his mother, who died in 1840, then with his sister, Jane, until she died in 1857 and then with another sister, Mary, and her daughter, Ann. He died aged 77 in 1859, in The Square – where Stockton library and the police headquarters are today – and was buried in Norton churchyard.

As he had never sought fame, or profit, as the inventor of the match, his light was allowed to go out. In his own lifetime, a high profile Bradford businessman and MP, Sir Isaac Holden, was generally given the credit for his idea in 1829, and John’s day book, which is now in the Science Museum and which proves his place in history, ended up in a skip.

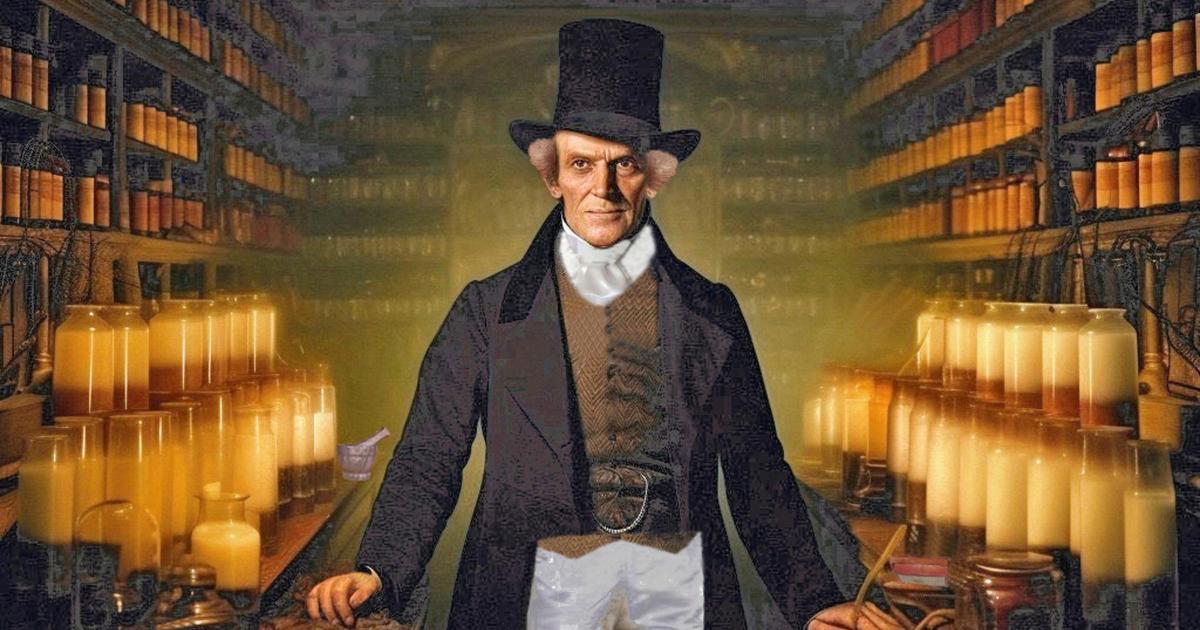

He died a year after Darlington’s Edward Pease. Despite Edward’s personal misgivings, he had several likenesses made in his latter years so we know what the Father of the Railways looked like, but because John was unacclaimed, no fully verified likeness is known to exist of the Father of the Match. Indeed, in 1977, when Stockton unveiled a statue of John on the site of his old shop, it was later discovered that the picture that it was based on was probably of a completely different John Walker (1732-1807), who was a well known London actor and lexicographer who found fame in 1775 by publishing Walker’s Rhyming Dictionary.

For the 200th anniversary, the British Matchbox Label & Bookmatch Society has had AI draw up a likeness of Stockton’s John Walker from contemporary descriptions.

It has also received a grant from the National Heritage Lottery Fund to make a film celebrating John’s achievements, and it will be given its world premiere at Preston Park Museum on May 29 – which would be John’s 244th birthday.

The society of phillumenists is holding an exhibition and other events at the Parkmore Hotel near the museum from May 29 to 31. For more details, see phillumeny.com or email johnwalker2026@phillumeny.com

- With many thanks to Mike Prior of the society. More on John Walker’s disappearing day book next week