This year the V&A opens its new outpost in east London. In 2025 it unveiled the so-called Storehouse, and its new V&A East Museum opens in April 2026. V&A East is part of a new cultural campus, on the site of the 2012 Summer Olympics, dedicated to collections, education and policy.

Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), the architecture firm best known for the giant Shed at the end of Manhattan’s High Line, the Storehouse serves as the new home for hundreds of thousands of objects that are not on display in the Museum’s main galleries in South Kensington.

It will be joined by the V&A East Museum, which will aim to spotlight making and the power of creativity to drive social change. It will open with the exhibition The Music Is Black: A British Story, which will reveal how Black British music has shaped British culture.

When the V&A East Storehouse opened it was met with both critical and popular acclaim, offering a beleaguered museum sector a glimpse of what London’s deputy mayor for culture called “the museum of the future”. However, if the V&A has created a new kind of institution, it’s fair to say, it has done so by going “back to the future”.

Indeed, that was the title of one of the early presentations I myself helped to create in 2016, when I was the V&A’s director of research and collections, to secure the approval of both the Museum’s Board of Trustees and London’s Mayor.

À lire aussi :

How the new V&A Storehouse is reshaping public access to museum collections

We drew inspiration from our recent record. As it happens, the three-year period during which V&A East was conceived saw three of the most successful exhibitions in the Museum’s history – David Bowie Is (2013), Disobedient Objects (2014) and Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (2015). Each of these exhibitions was a masterclass in museology (the practice of organising, arranging and managing museums) devoted to subjects once seen as difficult if not impossible to display.

We also met with people who had designed ambitious commercial and cultural infrastructures, including one of Germany’s largest hardware chains and one of Australia’s busiest public libraries. We visited other institutions devoted to giving new access to non-displayed collections such as Glasgow’s Museums Resource Centre and Rotterdam’s Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, whose dramatic Depot opened in 2021 as “the world’s first publicly accessible art storage facility.”

These new projects pointed us, in turn, to a history that stretched back to the middle of the 19th century, when the V&A grew out of the Great Exhibition of 1851. This first World’s Fair attracted more than six million visitors and provided both collections and capital for the South Kensington Museum (the precursor to the V&A and the Science Museum). This institution was the first to offer food to visitors and evening hours. It was also supported by the first system of artificial lighting.

The decades that followed the fair saw pioneering developments in how museums were run. There were strides in technologies of reproduction such as photography and plaster casts. There was increasing circulation of collections to remote locations. Makers and artists were incorporated more into the galleries. There was also a core commitment to integrating research and teaching in the museum.

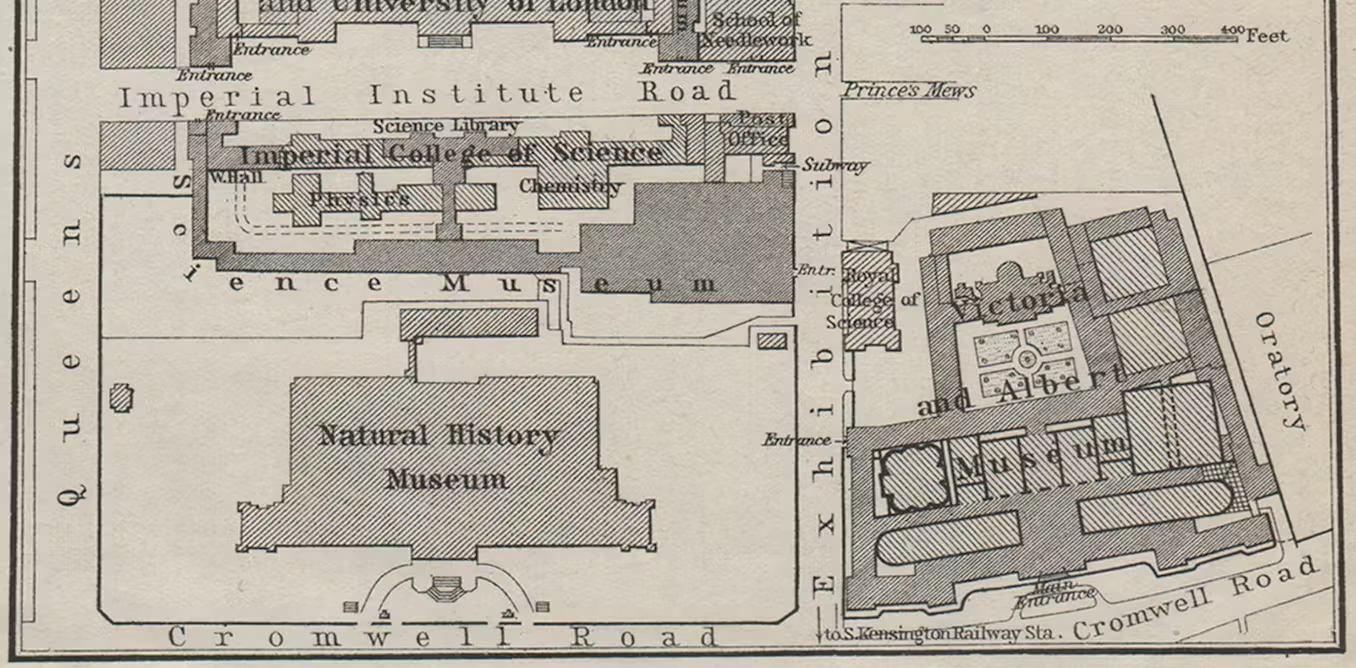

In those years, the Victoria and Albert Museum became part of a campus (known half-jokingly as Albertopolis) bringing together complementary institutions devoted to collections, education and policy. This was the explicit model not only for V&A East but for the redevelopment of the entire Queen Elizabeth Park in the wake of the 2012 Summer Olympics. In planning both the Storehouse and the new museum that will open next spring, we worked closely with partners (first UCL and the Smithsonian and later Sadler’s Wells, London College of Fashion, BBC Symphony Orchestra and others) who could create new synergies with old collections.

V&A

The V&A East Storehouse may well be the world’s largest cabinet of curiosities. It is certainly the most democratic: the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new facility in East London is free to visit and sits at the intersection of four of the UK’s most diverse and deprived neighbourhoods.

“It holds everything,” according to the V&A’s website, “from the pins used to secure a 17th century ruff to a two-storey section of a maisonette flat from the Robin Hood Gardens housing estate, demolished in 2017.” Other artefacts include The Kaufmann Office, the only complete interior by architect Frank Lloyd Wright outside of the US.

Visitors can not only see these “reserve collections” through a dizzying vista of open shelving but can order up to five items for a closer look. They can explore displays made by artists-in-residence and members of the community. They can look down through the glass-panelled floor into a state-of-the-art conservation lab. The project puts a national collection into the hands of the people and makes the experience no more daunting than a trip to the local Ikea, or, for that matter, the Westfield Shopping Centre, through which most people will pass on their short walk from Stratford Station.

When the project was conceived, Martin Roth, the V&A’s Director, asked us to turn the museum inside out, giving our visitors new insights into how collections are made, preserved and shown. Gus Casely-Hayford, the Director of V&A East, wants to bring a different demographic to the V&A, including local people who may never have been to a museum.

Its opening will complete East London’s new cultural campus. Only time will tell if the experiment of V&A East is as successful as Prince Albert’s visionary model in South Kensington.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.