The Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are highly vulnerable to global warming and scientists are being increasingly worried about the possibility of large parts of the ice sheets collapsing, if global temperatures keep on rising.

Scientists have identified three elements that could be triggered, putting the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica at further risk.

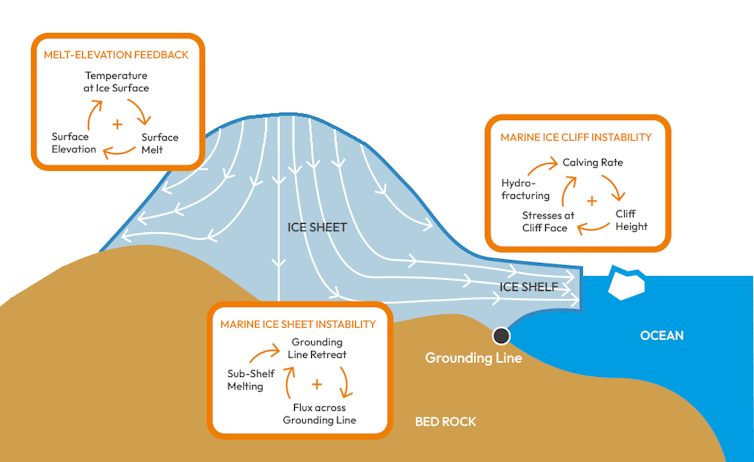

These three instabilities are marine ice sheet instability (Misi), marine ice cliff instability (Mici) and surface elevation melt instability (Semi).

The first one (Misi) occurs when the seafloor beneath the ice sheet slopes downwards toward the interior of the ice sheet. The floating platforms of ice that fringe the Antarctic continent, ice shelves, are too weak to help slow down the ice from flowing into the ocean.

Because of this, the retreat of the ice sheet will happen at an accelerated pace and might become irreversible. When this happens, ice thickness increases inland, meaning that more ice is transported from the ice sheet to the ocean, causing the ice sheet to thin and further retreat.

The second factor (Mici) is linked with the collapse of ice cliffs, left after the disintegration of an ice shelf. These ice cliffs, if they become taller than a 30-storey building, are structurally unstable and would collapse through hydrofracturing.

This is a process through which surface meltwater fills crevasses, forcing fractures to rip open and causing the ice shelves to disintegrate. Their collapse would trigger a rapid retreat of the ice sheet as further, taller ice cliffs – also prone to failure – would become exposed behind.

The third one (Semi) relates to when the melting of the ice sheet causes its surface elevation to decrease, exposing it to higher air temperatures and further increasing melt.

Illustration by Ricarda Winkelmann based on the Global Tipping Point Report

Which regions are most vulnerable?

West Antarctica, which is home to some of the fastest moving glaciers in the world including Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, is particularly vulnerable to global warming.

Satellite observations have revealed that these glaciers have retreated, thinned and are flowing faster to the ocean, indicating that Misi is potentially already under way in this region. At the same time, computer models have shown that the retreat of these glaciers will continue in the future.

So far, marine ice cliff instability has been simulated in an ice sheet model but has never been observed in the real world. The conditions that might lead to the formation of such tall ice cliffs and whether their collapse would lead to such dramatic consequences are still poorly understood.

But more glaciers could be at risk if they were to lose their ice shelves, potentially exposing unstable ice cliffs.

Surface melt instability is of particular concern in Greenland where surface melt has increased in the past decade and is becoming the main driver of ice losses.

What would happen?

If one (or several) of these instabilities are triggered, there would be an irreversible retreat of parts of the ice sheets, raising sea levels much faster than currently planned. It would still take centuries for the ice across whole regions to fully retreat.

But it could take just under 300 years, under a catastrophic Mici-driven retreat in west Antarctica. So we would already see a much higher contribution of the ice sheets to rising sea levels by 2300, with more frequent coastal flooding worldwide.

As a rule of thumb, for every centimetre of sea level rise, an additional 6 million people are at risk of coastal flooding.

According to the latest IPCC report, sea levels are predicted to rise between 0.3 and 1.6 metres by 2100, depending on future greenhouse gas emissions. However, an increase of more than 15 meters by 2300 cannot be ruled out.

Satellite observations and computer models help us understand how Greenland and Antarctica are changing and how they will continue to do so in the future. Analysis of satellite records shows that regions of both ice sheets are thinning and flowing more rapidly than before. Using computer models, self-sustaining mechanisms that could lead to increased ice sheet melting in the future have been identified.

My international team, supported by the European Space Agency, is bringing together experts in satellite remote sensing and numerical modelling to determine how close the polar ice sheets are to crossing “tipping points”, beyond which their retreat will become irreversible.

However, there is still much to understand and to research around the triggers of these instabilities, and some computer simulations suggest that

ice cliff failure might not lead to the dramatic outcome that some researchers have predicted.

Understanding more about what this means for future sea level rise will help reduce future risks so that we can avoid the dramatic human, social, and economic consequences that would come with more frequent and severe coastal flooding, storm surging and coastal population relocation.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 47,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.