What if the pages of an old book could tell us who touched them, what medicines they made, and even how their bodies responded to treatment?

Renaissance medical recipe books are filled with handwritten notes from readers who tested cures for everything from baldness to toothache. For years, historians have studied these annotations to understand how people experimented with medicine in the past. Our recent research goes a step further. My colleagues and I have developed a way to read not only the words on these pages, but also the invisible biological traces left behind by the people who used them.

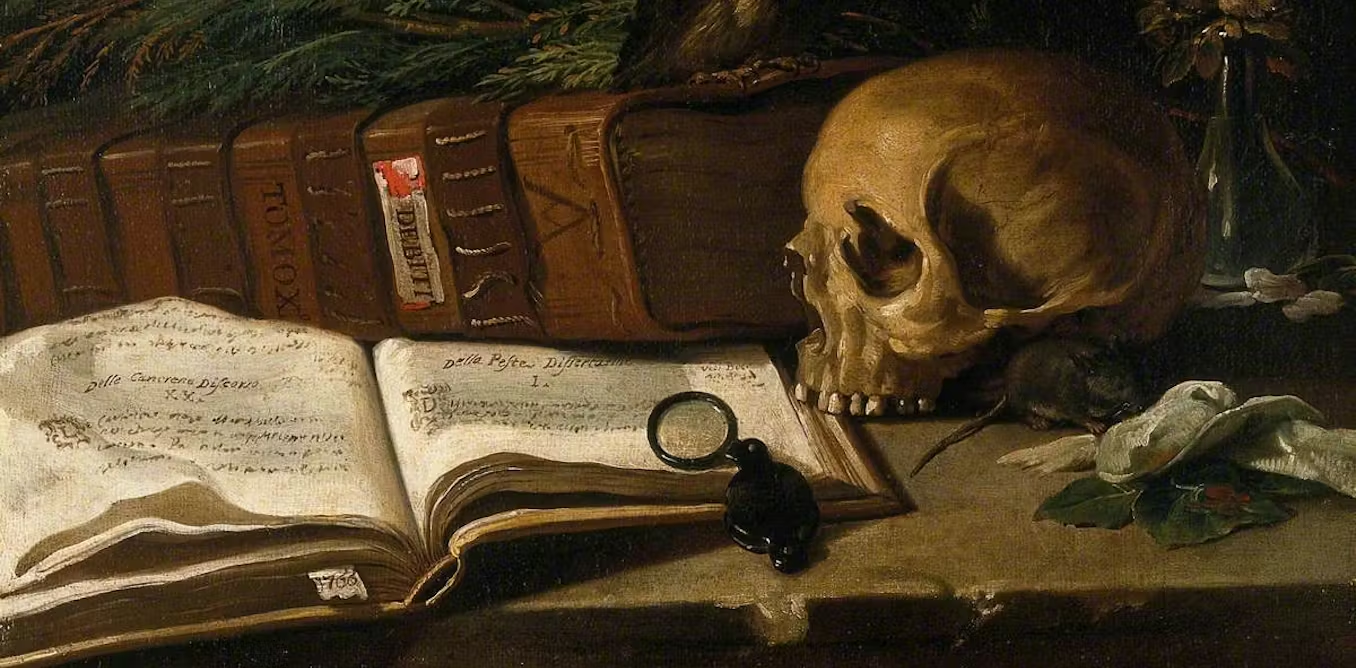

Thousands of handwritten manuscripts and printed books survive from Renaissance Europe that record medical recipes used in everyday life. These were not rare or elite volumes. Many were printed medical “bestsellers” that circulated widely, then personalised by readers who added notes in the margins. Which recipes worked best? Which ingredients could be swapped or improved? Far from being static texts, these books were working documents. The Renaissance was an age of medical innovation, shaped by hands-on experimentation and repeated trials.

For the first time, we were able to sample and analyse invisible proteins left behind on the pages of these books by the people who handled them.

This work is a form of biochemical detective work. Every time a 16th-century reader touched a page, they deposited tiny traces of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. These traces can now be sampled using specialised film diskettes produced by SpringStyle Tech Design, which gently lift material from the surface of paper without damaging it. We sampled printed German medical books from the 16th century now held at The John Rylands Research Institute and Library at The University of Manchester. The protein samples were analysed in laboratories at the Universities of York and Oxford, while the Rylands Imaging Laboratory used advanced imaging techniques to recover faded or obscured text.

Focusing on printed books matters. Because these volumes were produced in multiple copies, we can compare biochemical traces across similar texts, helping us distinguish between what the book prescribed and what individual readers actually did with it.

This combined approach allowed us to recover remarkable information about the people who used these books, the substances they handled and the remedies they prepared. When read alongside archival sources, it offers new insight into how Renaissance medicine worked in everyday life.

On pages recommending specific remedies, we identified protein traces from the ingredients named in the recipes themselves. Watercress, European beech and rosemary appeared alongside instructions for treating hair loss or encouraging the growth of head hair and beards.

This focus on hair is not surprising. With the rise of portraiture and the expanding trade in combs and mirrors, the cultivation of beards and new hairstyles became fashionable in the Renaissance. Hair was highly visible, socially meaningful and deeply connected to ideas of health and masculinity.

Wasteful recipes

Some findings were more startling. Near a recipe proposing an extreme treatment for baldness, we detected traces of human excrement.

This closely reflects Renaissance ideas about hair. In medieval and early modern medical thought, hair was understood as a bodily excretion, grouped with substances such as sweat, faeces and nails. As scholars have bluntly put it, “hair was shit”. From this perspective, using human waste to treat hair was not grotesque but logically consistent.

We also identified proteins from bright yellow flowering plants near recipes for dyeing hair blond. These plants were not listed among the written ingredients. We cannot identify the species with certainty, but their presence suggests readers were experimenting beyond the instructions on the page, guided by colour symbolism and perceived medicinal properties. Here, experimentation becomes visible not just in marginal notes, but in the biological record itself.

Other protein traces point to the use of lizards in haircare remedies. Lizards were classified in Renaissance natural philosophy as poikilothermic animals, meaning their body temperature changes with the environment. Hair growth was believed to depend on internal bodily heat. Increasing heat was thought to stimulate hair growth, while excessive heat could destroy it. The presence of lizard proteins suggests practitioners were actively testing these competing theories by processing animal materials into remedies.

Hippo teeth

Then there is the hippopotamus. We recovered proteins consistent with hippopotamus material on pages discussing dental problems. In the margins, readers complained about foul-smelling teeth, toothache and tooth loss. In Renaissance medicine, hippopotamus bone was believed to strengthen teeth and gums and was sometimes used to make dentures. Its presence suggests that readers in 16th- and 17th-century Germany had access to exotic medical materials traded across long distances.

Our methods combine close historical reading with laboratory analysis, allowing historians to study medical practice in ways that were not previously possible. They bring together forms of evidence that are usually kept separate: texts, bodies and materials.

Perhaps most intriguingly, we also identified proteins with antimicrobial functions, including molecules commonly found in human immune responses, such as those associated with inflammation and defence against bacteria. These proteins help the body fight infection. Their presence suggests that the people handling these books were not only preparing remedies but were themselves experiencing illness or healing, leaving traces of immune activity behind.

In this sense, we can glimpse immune systems reacting to disease and treatment on the pages themselves. We are only beginning to understand what this evidence can reveal, but this work opens up entirely new ways of studying how Renaissance medicine was practised, tested and lived.