Over Christmas, vegetables, bananas and insulation foam washed up on beaches along England’s south-east coast. They were from 16 containers spilled by the cargo ship Baltic Klipper in rough seas. In the new year, a further 24 containers fell from two vessels during Storm Goretti, with chips and onions among the goods appearing on the Sussex shoreline.

For most people this is a nuisance – or perhaps a bit of fun. For oceanographers like me, who study tides and currents, it is also an accidental experiment – a rare chance to watch the ocean move things around in real time. Think of it as a very large message in a bottle.

In reality, cargo has been falling off ships since traders first went to sea. What has changed is that, in the modern world, most goods are transported in standardised containers. Apart from oil, gas, vehicles, bulk grain, aggregates – and people – pretty much everything is moved this way.

More than 250 million containers are shipped around the world each year, and it is likely that over 80% of goods in your home travelled at some point in a container by sea.

reppans/Alamy

Losses are rare. Industry group the World Shipping Council estimates that over the past ten years an average of 1,274 containers a year have been lost globally, out of hundreds of millions transported. This figure does vary: in 2020 a single huge ship the ONE Apus lost around 1,800 containers of its 14,000 load in a Pacific storm, while in 2024 global losses were estimated at just 576.

Ducks go global

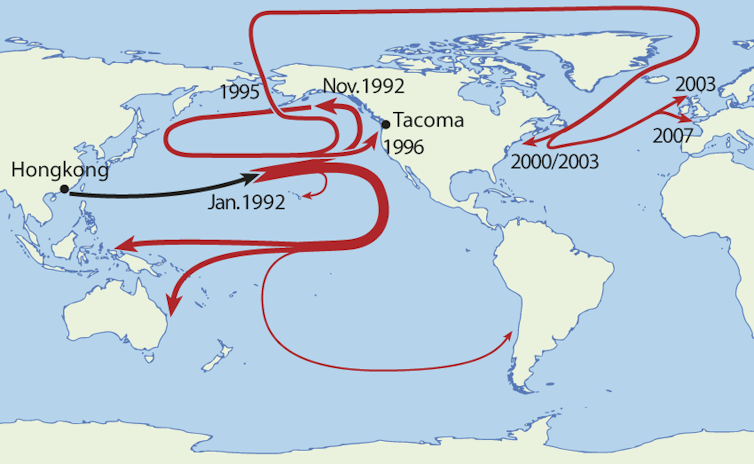

Some losses make the news in unexpected ways. In January 1992, 12 containers washed off the Ever Laurel in the North Pacific. One of these contained 28,800 bath toys – plastic beavers, frogs, turtles and ducks – which spilled into the ocean and washed up on beaches around the Pacific over the next decade or more.

Curt Ebbesmeyer and James Ingraham, oceanographers from Seattle, tracked these so-called “friendly floatees” around the world and used them to improve scientific models of ocean circulation. In more recent years I’ve looked at the progress of these floatees into the Arctic and beyond.

NordNordWest / wiki, CC BY-SA

Not all cargoes are this benign or useful. In January 2007, the MSC Napoli was hit by a major storm in the Channel and lost 114 containers, 80 of which washed up on beaches around Branscombe in Devon. Containers of wine, BMW motorbikes and perfumes drew locals to scour the beach for prizes but there were also far more sinister containers of explosives, weed killers, fertilisers and acid.

Both the cargoes and the containers themselves pose serious risks. Chemicals can destroy habitats, while containers can sometimes lurk one or two metres below the surface, kept semi-buoyant by trapped air, making them difficult to detect and capable of causing serious damage in a collision.

Designed for speed – not 100% security

Modern container ships are designed for speed and efficiency in port. A single 400-metre vessel can carry up to 25,000 containers, many towering high above deck like a block of flats. The containers interlock and are secured using industry standard fixings – one reasons cranes are able to rapidly move them around a port. In severe storms, however, the forces involved can exceed what the fixings are designed to withstand, and containers can be dislodged, particularly those at the edge.

MagioreStock / shutterstock

It is almost impossible to secure cargo 100% safely. To do so would mean smaller ships, with cargo held internally, reversing decades of efficiency gains. That would mean far more ships required to move the same volume of goods, higher costs for consumers, great fuel use per tonne of goods, and a higher overall risk of accidents. It would also clog up ports around the world.

The English Channel is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world and is regularly battered by storms. Southampton, the UK’s second busiest container port, is also one of only a few worldwide that can accommodate the largest container ships. It is therefore no surprise that container losses are often visible along England’s south coast.

Looking ahead, the risks are unlikely to diminish. Climate change is intensifying storms as oceans warm, while international trade continues to grow and ships become ever larger.

reppans/Alamy

The ship owners – usually through their insurance companies – are responsible for cleaning up spills, but the system only works if the losses are reported. Until now, containers lost at sea have often gone unreported or their contents have been barely documented.

However, from January 1 2026, new international rules introduced by the World Shipping Council working with the International Maritime Organisation (the UN Agency responsible for shipping) will require ship owners to report all cargo losses and their contents. While this may not prevent containers being lose at sea, it should improve tracking, recovery and accountability.

If you see a container on a beach, resist the temptation to see it as an early Christmas present. You should report it immediately to the coastguard – scavenging wrecks can count as theft. In the UK, who owns what washes up is decided by a single civil servant with the grand title of the Receiver of Wreck. Critically, that container may contain a far less pleasant cargo that could ruin your Christmases for years to come.