This summer, Polish bakery group Putka started offering English classes to ease communication among its swelling international workforce.

Located on the western outskirts of Warsaw, the company has struggled to attract locals and has turned to workers from countries as diverse as Senegal, India and Colombia, who now account for half its 500-strong production team.

Chief executive Grzegorz Putka, the fourth generation of his family to run the business, said the foreign workers had integrated well but a lot more were needed: “We simply cannot sell as much as we would if we could employ foreigners more easily.”

Business leaders and analysts have warned that Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s recent pivot on migration, though part of a toughening stance at EU level, risks hitting businesses that need migrant labour to offset Poland’s ageing workforce.

Poland’s labour market is the tightest since 1990, when the country started its transition from communism. Its 2.9 per cent unemployment rate is the second lowest in the EU after the Czech Republic, and Warsaw, according to Eurostat, is the region with the highest employment rate in the bloc.

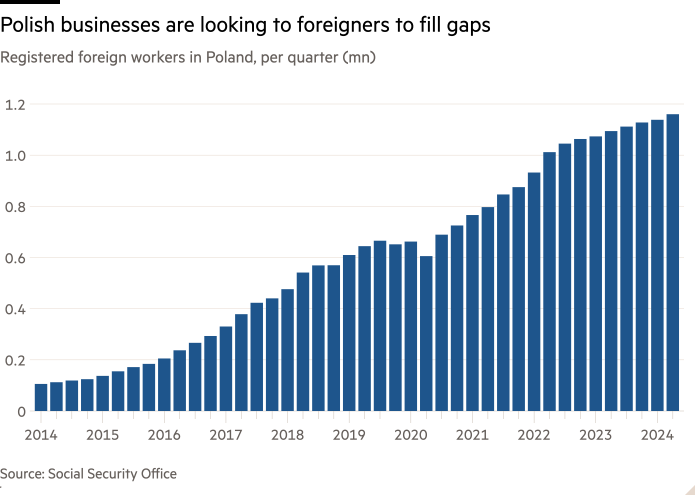

In response, businesses have increasingly looked abroad to fill the gap. The country now has 1.16mn registered foreign workers — 10 times more than a decade ago, according to Poland’s social security office.

But while claiming to keep Poland open to skilled foreign workers, Tusk adopted a series of measures aimed at protecting the country’s security and showing he is tough on illegal migration ahead of presidential elections next May.

His government cut the number of all visas issued in the first half of this year by 31 per cent compared with the same period in 2023. Rules for student visas were also tightened to prevent misuse by incomers planning to work rather than study.

The Tusk administration also continued its predecessor’s policy of beefing up security along the border with Belarus to stop what Warsaw calls a “hybrid war” waged by Russia when facilitating the journey of Middle Eastern migrants to cross the frontier into Poland. Tusk in October announced Poland would suspend the right to asylum for migrants coming via Belarus — a step broadly backed by western leaders.

“We see the EU, along with Britain, experimenting with what might work,” foreign minister Radosław Sikorski said in an interview. “[Controlling] migration is important in Britain, it’s important in Germany, it’s important in the US, so why shouldn’t it be important in Poland?”

Tusk argues that his strategy of allowing only skilled workers into the country can ensure both economic growth and security. “To bring in lots of people who are totally unqualified is not the right way,” he told a conference in the Polish town of Sopot last month.

But the clampdown “could kill one of the most important sectors for Poland”, warned Maciej Wroński, president of Transport and Logistics Poland, which represents the country’s truck operators — the EU’s largest national fleet.

“The Tusk government has made everything harder, to get new foreigners but also to renew visas for those who already work for us,” he said.

Two-thirds of Poland’s foreign workforce stems from Ukraine, but Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022 significantly changed its demographics, as some men returned to their home country to join the war effort, while women and children stayed in Poland. This has created labour shortages particularly in male-dominated sectors, such as transport and construction.

The average age of Polish truckers is 55 and more than half of Poland’s 300,000 long-haul drivers are non-EU nationals, according to Wroński. “Young Polish people from Generation Z want to be YouTube influencers, not drivers,” he added.

The restrictions come “just when we are seeing our depopulation and bad demographics clearly for the first time”, said Andrzej Kubisiak, deputy director of the Polish Economic Institute, a state-funded think-tank.

Poland recorded its sixth consecutive year of population decline in 2023, with numbers falling by 133,000, according to Eurostat. Based on its current demographics, Poland’s labour market will lose 2.1mn workers by 2035, according to Kubisiak’s institute.

At the Putka factory, the switch to a multinational workforce has also increased staff rotation, due to their limited-stay visas. Paying specialist employment agencies to arrange workers’ immigration paperwork and housing means that foreign staff are about 10 per cent more expensive than Polish employees, the company said.

But workers say they are glad to be part of such an international environment. Oleksii Totkal, who fled Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region in 2022, said of his four Indian colleagues that he was “learning about their traditions and all sorts of things that I never heard about in Donbas”.

Ukrainians’ eventual return home will intensify labour shortages and require Poland to admit more workers from across the world, said Danuta Hübner, a former professor at the Warsaw School of Economics and Poland’s first EU commissioner.

“Maybe our streets will one day look [as diverse as] the streets of London — which is hard to imagine when you look at our politicians and think how happy they would be about this,” she said. “But I see no other option.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login