Days after being hit with a hefty rise in business taxes by UK chancellor Rachel Reeves, a group of 25 senior executives and local mayors gathered in Birmingham to discuss how to kick-start economic growth.

Top of the agenda at the mini-summit convened by the CBI was how the Labour government’s ambitious plans to introduce a new industrial strategy could bring investment to high-growth sectors of the economy.

“Despite the Budget there was a buzz in the room about the possibilities, but a realisation that the pressure of new tax rises makes getting the industrial strategy right all the more crucial,” said one person present.

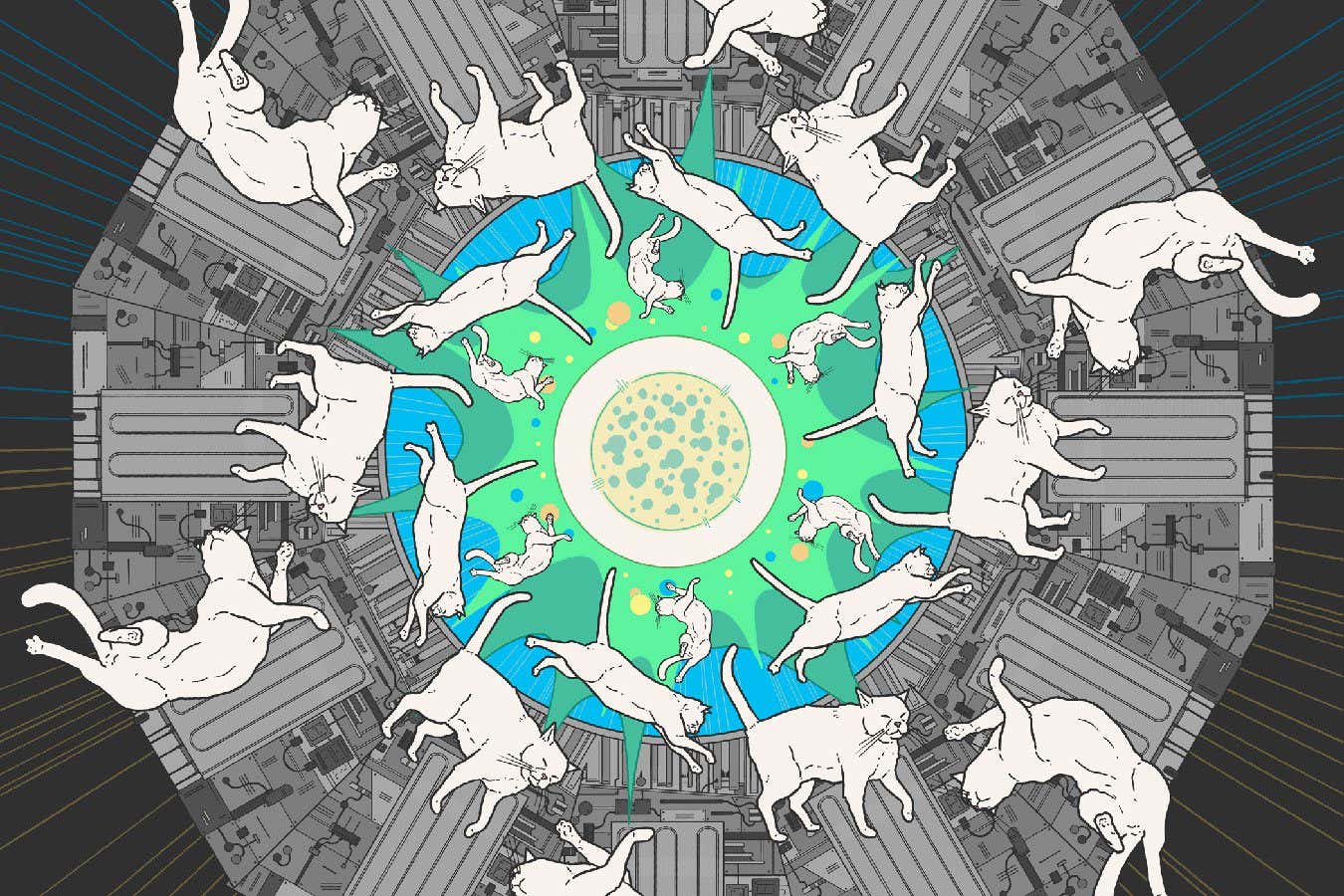

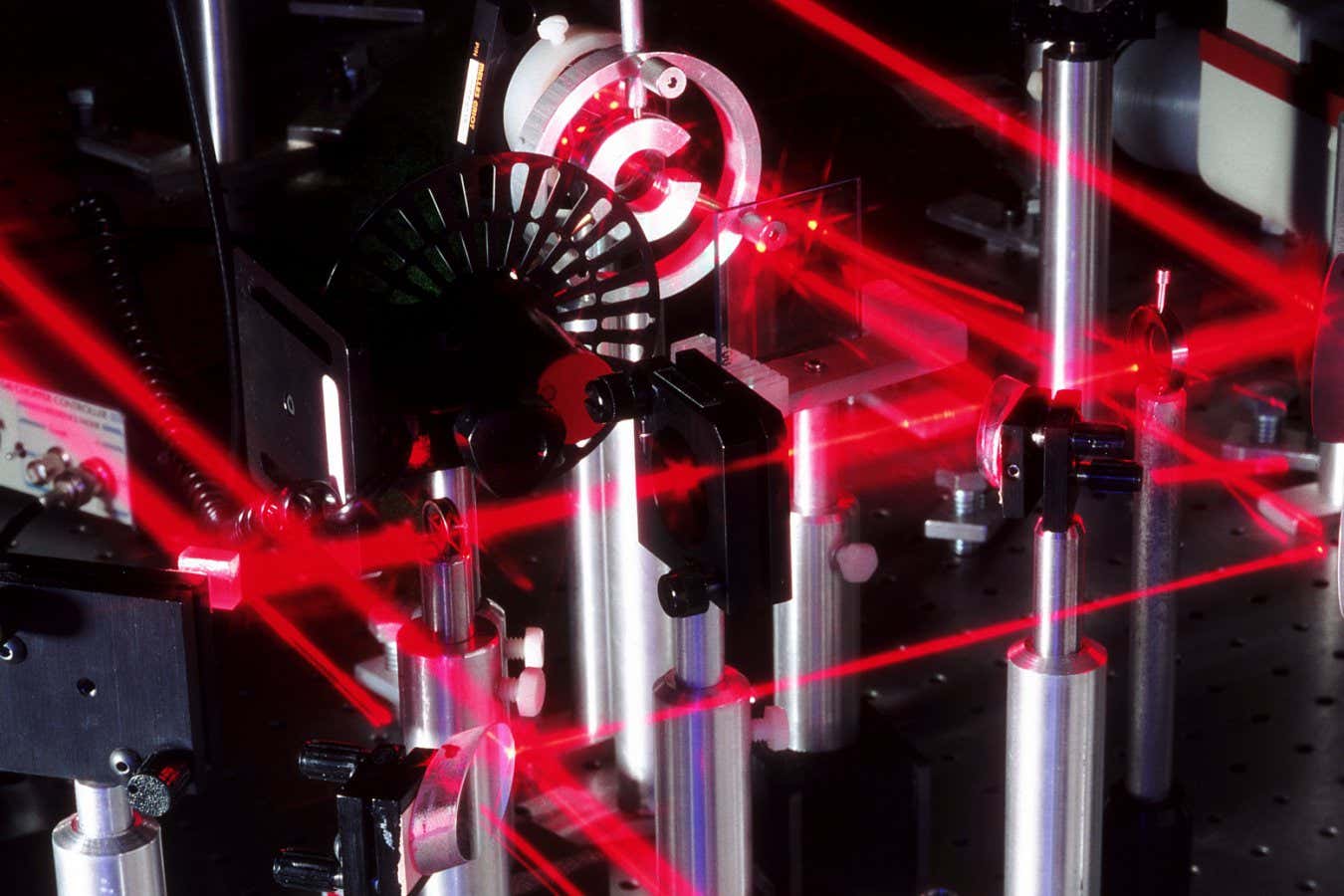

The Birmingham meeting was part of the rush by business and local leaders to shape Labour’s flagship growth policy. So far, a green paper has outlined a focus on eight high-growth sectors — including advanced manufacturing, clean energy, defence and life sciences — but the detail of that plan is yet to be thrashed out.

There is a growing realisation — reflected in the room in Birmingham — that there needs to be co-ordination between regional rivals.

“We have to accept that not everyone can be famous for tech and life sciences,” said one person at the meeting, which included seven mayors and executives from major companies including Google, Legal & General, Atkins and AstraZeneca.

The race to be chosen

A consultation by the Department for Business and Trade on its Invest 2035 green paper will close on November 24, leaving businesses, trade groups, universities, councils and regional mayors all rushing to prepare submissions.

Successful applicants stand to receive “temporary catalytic government support” — expected to include a range of measures including grants, skills support and planning and regulatory reforms — to scale up their industries, according to the document.

“The green paper is a good framework for promoting a bloody good discussion about the opportunity of the UK to grow,” said Paul Drechsler, former president of the CBI. “The challenge will be the sheer volume of feedback and distilling that into a tangible action plan.”

Experts warn that for the government to be successful, and crowd in the billions in private sector investment it is seeking, it must be prepared to make clear choices.

Kelly Becker, president of Schneider Electric’s business in the UK, Ireland, Netherlands and Belgium, said it would be better to prioritise “progress over perfection”.

“I absolutely believe there will have to be a deeper prioritisation process because, as the chancellor said [in the Budget], there isn’t an endless stream of money to be had,” she added.

Picking places

Simon Green, chief executive of the Humber freeport — which includes major chemical and energy companies — said the government needed to back industries where the UK has a real competitive advantage, such as green tech and aerospace.

England’s metro mayors are developing their proposals, in many cases based on long-established geographical clusters. While both Greater Manchester and South Yorkshire have pronounced strengths in advanced manufacturing, for example, the former focuses on advanced materials, while the latter has specialisms in aerospace and nuclear.

These priorities are being fed into the mayors’ wider growth plans, in parallel with emerging devolution policy, which promises to provide them with further powers, for example on skills and planning.

Nigel Driffield, a professor at Warwick Business School, who is contributing to six different submissions by trade groups and universities to the business department consultation, said the government must avoid a destructive competition between areas.

“We need to ensure that the strategy makes an overall difference to growth and isn’t just a case of ‘beggar thy neighbour’,” he said.

Struggling to be heard

Meanwhile, for the roughly 50 per cent of the country without the political megaphone provided by a mayor, business is working out how to attract the government’s attention.

“Lancashire has the biggest capability and number of businesses and employees per square mile in aerospace and defence across Europe, not just the UK,” said Paula Gill, chief executive of the North West Aerospace Alliance.

The area counts BAE Systems among its major employers, but the fact it does not have a mayor means it has less of a “voice at the table”, she added.

Karl Tucker, chair of the Great South West partnership, which represents regional businesses including a large aerospace cluster, was similarly frustrated.

“At the moment nothing south of M4 gets a mention, and it feels like we’re being ignored,” he said.

Skilling up

The government has already signalled backing for three sectors in last month’s Budget, confirming £950mn of government funding for aerospace, £520mn for life sciences and £2bn for the automotive industry over the next five years.

However, chief executives and trade bodies warn of a yawning skills gap in several industries, a problem the government has promised to address via a new body, Skills England, designed to unify the UK’s fractured provision of training.

Stephen Phipson, head of Make UK, the manufacturing trade body, said the government’s ambitions depended on its ability to train enough workers to deliver its plans.

“If skills aren’t at the heart of this, you can forget everything . . . It’s about the transition to net zero and how you’re going to train up hundreds of thousands of workers,” he added.

Clive Higgins, chief executive of defence giant Leonardo UK, said the government needed to follow through on its promise to create a more flexible apprenticeship system, to “drive collaboration” between companies, local government and colleges.

Drilling down

As well as individual company and local government proposals, the government can also expect submissions from think-tanks, trade groups and university bodies such as the Centre for Sectoral Economic Performance at Imperial College London.

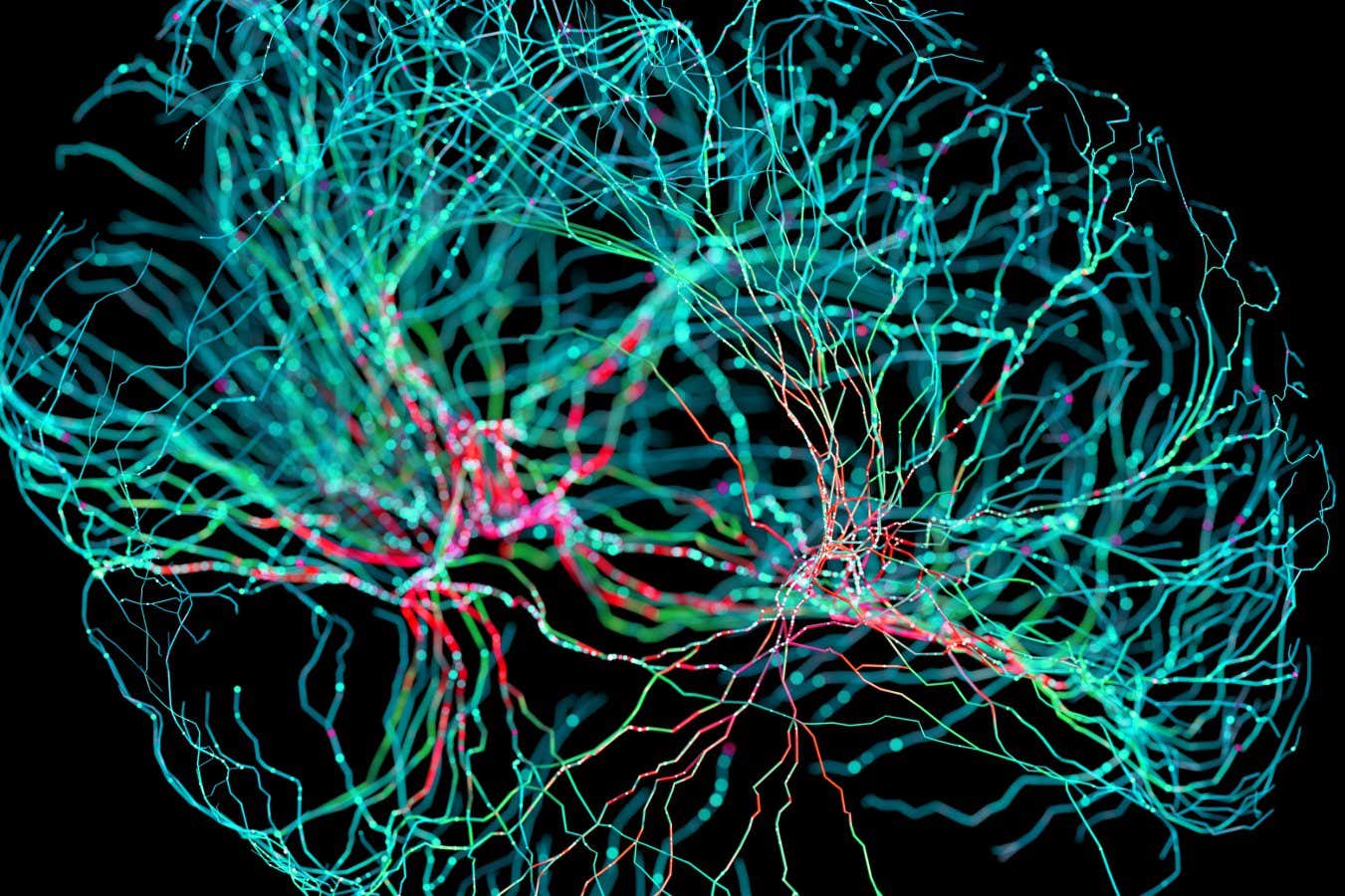

Last month CSEP published a strategy for the health tech sector that outlined a plan to increase R&D spending in the UK by 50 per cent and create 50,000 skilled jobs within five years.

James Moore, professor of medical device design at Imperial and co-director of the CSEP, said the analysis had shown what a highly targeted combination of faster regulatory approvals, industry-specific skills initiatives and bespoke tax incentives could deliver for the health tech sector.

“Budgets are tight. We do need more money in funding for early stage start-ups, but we have to lead with ‘this is what industry can do’,” he said.

Driffield of the Warwick Business School argued that the government should opt for highly targeted and tightly focused interventions to fix gaps in the market.

“If they do this nicely, they should end up with a matrix: individual sectors saying ‘this is our case’ and specific locations saying ‘this is ours’ and they ought to map one on to the other,” he said.

Data visualisation by Amy Borrett in London, additional reporting by Michael O’Dwyer in London

You must be logged in to post a comment Login