An article on October 23 wrongly reported the outcome of a Hampshire county council cabinet meeting. Waste recycling centres will be spared and the use of school traffic controllers will be reviewed, not cut as wrongly stated.

Business

Hampshire county council cabinet meeting

Business

a new route to private markets?

Individual investors are about to be offered a new route into private market assets, with the arrival of the UK’s first long-term asset fund (LTAF) aimed at the retail wealth management market. How should individuals judge this new arrival on the investment block?

LTAFs are the UK’s version of the so-called semi-liquid fund structures used in other markets to hold illiquid, private market assets while allowing investors — mainly wealth management and private banking clients — periodic windows in which they can exit.

In contrast, traditional private market funds — structured as institutional limited partnerships — require cash to be locked away for 10 years or more.

Asset manager Schroders is set to launch the new vehicle through advisers and wealth managers in the coming weeks, with a minimum investment of £10,000, far below the six-figure sums required to gain entry to conventional private markets funds. Its LTAF will channel investors’ money into Schroders Capital Semi-Liquid Global Private Equity, a £1.8bn Luxembourg-regulated fund that holds stakes in around 280 small and mid-market private companies in Western and Asian markets.

The UK approved the LTAF framework in 2021, initially to enable “defined contribution” pension schemes, where retirement outcomes depend on investment performance and contributions, to invest more in illiquid assets such as private equity, private credit and infrastructure. It was then adapted for the retail market with these versions now appearing structured as open-ended investment companies (OEICs).

However, mindful of the liquidity problems that have plagued commercial property OEICs at times of market stress, LTAFs do not offer daily dealing. Instead, they accept new money once a month and require at least 90 days’ notice for redemptions. Even then, there is no guarantee investors will be able to withdraw all their money — LTAFs limit liquidity to 5 per cent of the fund’s net asset value (NAV) each quarter. If sell orders exceed that level, redemptions are gated so the fund can avoid a fire sale of assets.

Industry figures say the high-profile collapse of a flagship equity income fund run by former star stock picker Neil Woodford, trapping 300,000 investors, cast a long shadow over illiquid assets.

“Gating in the UK market has very negative connotations because of what happened in the property sector and at Woodford,” says James Lowe, sales director for private assets and investment trusts at Schroders. “I’ve had lots of conversations with wealth managers about this, quite rightly.

“Gating is not inherently bad — it protects the integrity of the underlying assets and the remaining shareholders in the fund. As long as it’s explained clearly at the start and investors go in with their eyes open, it can be a reasonable mechanism to allow us to have open-ended funds that sit somewhere between investment trusts and limited partner funds [with 10-year lock-ups].”

This highlights a key issue with LTAFs that would-be investors and their advisers must consider — the trade-offs that are inherent in the fund structure.

As open-ended funds, LTAFs allow investors to buy and sell units at the fund’s net asset value (NAV), avoiding the risk of having to accept a discount to NAV when they sell, as can happen with closed-end funds such as investment trusts. LTAFs also deploy investors’ money within a few weeks of their investment. With limited partnership funds, by contrast, investors commit money at the outset but do not hand all of it over at once. Instead, they must have capital available so that it can be called on in stages over the first few years of the fund’s life as the managers acquire new assets.

The quid pro quo for this ability to invest at NAV and start generating a return on their capital almost immediately is that the fund’s liquidity is periodic and limited in size.

That, in turn, requires a further trade-off. Managers that launch LTAFs must satisfy regulators that they are holding enough liquid assets in the fund to meet likely redemptions. For a private equity LTAF, that in practice means holding up to 20 per cent of its NAV in cash and other liquid assets — enough to provide 5 per cent quarterly liquidity for a year ahead. This inbuilt “cash drag” is likely to mean that the returns investors see from LTAFs do not keep pace with those reported for institutional funds.

Then there is the question of fees. In the case of the private equity LTAF that Schroders is about to launch, annual fees are expected to be around 2.89 per cent. Ongoing charges excluding performance fees for private equity-focused investment trusts range from 0.8 per cent to 2.8 per cent, according to Winterflood data.

Retail LTAFs, such as the Schroders vehicle, sit in the category of Restricted Mass Market Investments, which opens them up to advised and discretionary private clients while retaining protections that apply to other products targeted at retail investors. If LTAFs are ultimately offered to self-directed investors via execution-only platforms, people that buy them will be classed as Restricted Investors and will have to undertake not to put more than 10 per cent of their investable assets into them. There is no clarity so far about how platforms would police this 10 per cent limit.

The arrival of retail LTAFs signals the start of a trend in the UK that is well advanced in other markets. The leading US-based private market managers regard private clients as a key fundraising priority — private wealth assets at Blackstone, the market leader, total $243bn, including semi-liquid funds. Continental Europe had around €37bn in Luxembourg-regulated semi-liquid “evergreen” funds by the first quarter of 2024. Another €13.6bn was held in ELTIFs, the EU equivalent or LTAFs, at the end of 2023, up 25 per cent in a year, according to Scope Group, the alternative investments analyst.

“What happens in the US spreads around the rest of the globe,” says Will Normand, a partner at law firm Travers Smith who specialises in structuring semi-liquid funds for asset managers. “So, Asia-Pacific trails the US but is ahead of Europe and Europe in turn is ahead of the UK. In Europe and the UK we are in the foothills of this.”

Allocations to private markets by their traditional users — institutions such as endowments, defined benefit pension schemes, sovereign wealth funds and family offices — have mushroomed over the past two decades. According to the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association, US states’ pension schemes achieved annual net returns of 11 per cent from their private equity portfolios over the 23 years to June 30, 2023, compared with 6.2 per cent for a global equity benchmark.

However, returns from illiquid assets have been weak recently as rising interest rates have pushed up the cost of debt used to fund deals. Advocates also argue that besides attractive net returns, adding private markets exposure to portfolios also brings diversification benefits.

UK private investors already have several ways to access private markets. Unlike many other countries, the UK has a large and varied group of listed closed-end funds — investment trusts — that hold assets including private equity, infrastructure, property and private credit. These are well understood by advisers and offer daily dealing — although large discounts to NAV can open up when markets become stressed.

Certified high net worth investors and self-certified sophisticated investors in the UK can now access limited partnership private market funds for themselves through online providers, such as Moonfare. Founded in Germany in 2016 by former KKR executive Steffen Pauls, Moonfare now has €3bn under management and says the UK is its second-biggest market in the Emea region, with more than 1,000 investors and total UK assets under management of more than €800mn.

How will LTAFs fit into the UK’s financial landscape? Much will depend on how the big wealth management firms decide to develop their private markets offering. A recent report by Bain & Co suggests assets under management in private markets will grow more than twice as fast as public markets between now and 2032, spurred by increasing interest from private investors. Wealth managers therefore have a strong incentive to provide access to these asset classes.

Data from Research in Finance, a consultancy, suggests that around 45 per cent of UK investment advisers and discretionary fund managers currently recommend or provide exposure to private market investments for clients.

Among mass-affluent discretionary fund managers and high net worth advisers the proportion rises to 60 per cent, with diversification and high potential returns among the main attractions cited.

About half of the high net worth advisers surveyed were familiar with LTAFs and 38 per cent found them appealing. However, the research also showed that more than a quarter of such advisers had clients that were already investing in private markets through conventional, limited partnership funds.

This suggests that LTAF providers face several challenges: building awareness and support for these products among wealth managers and investment advisers, and especially overcoming recent bad memories of the liquidity problems that have bedevilled open-ended funds that contain illiquid assets.

Beyond that, they will need to articulate a clear case explaining how this new type of fund fits into a set of portfolio options that ranges from highly liquid vehicles such as investment trusts at one end through to illiquid limited partnership funds at the other, and for which types of clients LTAFs are most appropriate.

And, of course, they will have to demonstrate the LTAFs can deliver the enhanced returns — after fees — and the diversification benefits that investors look for in private markets.

Business

‘Beetlejuice’ and the lost art of soft horror

Today we are pulling on our striped demon ghost suits for a special Halloween episode: a deep-dive on Tim Burton’s 1988 classic, Beetlejuice. It persists in our cultural memory, remade as an animated series, a theme park ride, a musical, and as of last month, a legacy sequel, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice. We talk about why it’s endured with such ferocity, how the sequel compares, and whether films like it even exist anymore. We also share our own, and listeners’, top Halloween films. Lilah’s joined by FT horror movie superfan Topher Forhecz and political columnist, film buff and Beetlejuice hater Stephen Bush.

——-

We love hearing from you. Lilah is on Instagram @lilahrap, and email at lilahrap@ft.com. And we’re grateful for reviews on Apple and Spotify!

——-

Clips this week courtesy of Warner Bros

Business

How the US election looks in the swing states

If you live outside a swing state, you might — if you really try — almost forget there is a tumultuous US election under way. If you live inside one, not so much.

Lawn signs. Billboards. Text messages. So many text messages. In the seven battleground states that will decide the US election, political ads are everywhere, all the time. The White House race is inescapable.

As one of the tightest presidential elections in living memory enters its final days, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump are criss-crossing the country to make their final pitch to voters in the swing states.

Their campaigns are there 24/7. While some people elsewhere in the US can tune out of the frenzy, voters in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are being inundated with some of the most sophisticated and targeted messaging and advertising in political history.

And some of that is just downright blunt.

There are the classic campaign placards pitched on lawns and in windows and crowding verges along roads, as well as television ads flooding the airwaves.

Added to the campaigns’ arsenals are digital ads, particularly on social media, and a steady stream of personalised text messages pleading for donations and urging people to turn out to vote on November 5, or before.

The 2024 election is on track to be the most expensive ever, with the vast majority of funds going to advertising.

The Harris campaign and its affiliated committees have pumped more than $1.1bn into advertising, almost double the $602mn spent by the Trump campaign and its aligned committees, according to the FT’s ad tracker.

The swing states that will decide the vote have received $1.36bn of the two campaigns’ combined spending. The biggest share — $373.5mn — has gone to Pennsylvania, considered the most crucial battleground state.

“I think everyone is just ready for it to be over,” said Tracee Malik, a real estate agent from the Pittsburgh area. “Pretty much the only commercials that we have now are the political commercials.”

Harris’s most-aired TV spots have focused on her prosecutorial and middle class background, defence of reproductive rights, and claims that Trump cares only about the wealthy. Others focus on her rival as being “too unstable to lead”.

Trump’s most-aired ads have been about the economy, blaming Harris and President Joe Biden’s economic agenda for the high cost of living. But his most played spot attacks the vice-president for supporting gender affirming care for prison inmates, telling voters: “Kamala’s agenda is they/them, not you.”

In Pennsylvania, Arizona and Nevada, Trump ads also slam Harris over immigration, while in Georgia and North Carolina, pro-Harris ads concentrate on abortion rights.

Is the barrage working? It’s unclear.

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories to inform, inspire and delight, free to read for 30 days. Explore FT Edit here ➼

“I hate that advertising,” said Vallon Laurence, a retired member of the US Navy who lives in Atlanta, Georgia. “If you go by the advertising . . . you don’t want either one of them.”

Local issues also feature in the campaigns. Pro-Harris ads in North Carolina link Trump to Mark Robinson, the Republican gubernatorial candidate who has been embroiled in a scandal over allegations — vehemently denied by him — that he posted racist comments on a pornography website.

Simultaneously, pro-Trump groups are sending texts assailing Harris and the Biden administration for a slow recovery effort from Hurricane Helene, which devastated the western part of the state.

On social media, the campaigns can target small groups of voters, tailoring content based on age, gender or even interests using memes, news or a chain email format.

The Harris campaign has spent more than $10mn promoting generic-looking Facebook pages with titles such as “The Daily Scroll”, boosting favourable news articles.

Democrats have also taken advantage of digital targeting tools to address women, particularly on abortion rights, blaming Trump for the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe vs Wade.

More than a quarter of the Harris campaign’s Facebook and Instagram ads have been seen by an audience that is at least two-thirds women. Virtually none had the same margins for men.

Pro-Harris super Pacs — political action committees, or fundraising and spending groups, that aren’t allowed to co-ordinate with the campaigns — have been targeting women even more aggressively: 51 per cent of their Meta ads reached a predominantly female audience, compared to only 2 per cent at equivalently male audiences.

But irritation with the flood of propaganda has spread, even to down-ballot races. A ferocious battle for a US Senate seat from Montana — which could decide which party controls the upper chamber of Congress — has exhausted local residents.

The state has had the highest ad spending per voter in recent weeks, surpassing the battlegrounds, according to Financial Times analysis.

“It just hits you in the face,” said Emma Fry, 21, a student in Bozeman who recently came home to find a pile of political flyers and letters on her porch.

“They’re absolutely everywhere. And at some point people are just annoyed,” she said. “We’ve got to pray for the day it’s just over, because we need to wrap this up.”

Additional reporting by Myles McCormick in Atlanta and Bozeman, Montana, and Oliver Roeder in New York; video editing by Jamie Han

Business

Impact humans have on biodiversity is catastrophic

In regard to Andrew Anderson’s contention that there is “no planetary crisis” (“Earth can live without us, just as it did for millennia”, Letters, October 22), it is not so much that the earth could survive perfectly well in the future without us, as much as the catastrophic impact we are having, and will have had, on its biodiversity by then.

We share the earth with other life forms that will not survive because of our brief span here. I believe a sixth mass extinction driven by human activity could be considered a planetary crisis.

Paul Littlewood

St Albans, Hertfordshire, UK

Business

FT Crossword: Number 17,877

FT Crossword: Number 17,877

Business

Barriers in way of funding the global green transition

Alan Beattie’s opinion piece “The magic pony of private finance fails to fund the global green transition” (Trade Secrets, FT.com, October 17) rightly dismisses the notion that small amounts of public money can mobilise vast sums of commercial capital for the green transition in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs).

But the problems go beyond the shortcomings of multilateral development banks and development finance institutions, and into the risk culture and regulatory incentives faced by private investors.

Pension funds in the UK allocated a mere £14.2bn, just 0.5 per cent of their assets, to EMDEs in 2022. This cautious approach is often driven by advisers whose interpretation of fiduciary duty focuses solely on financial returns rather than on environmental, social and governance factors — but even on these terms they may be missing out.

Our research shows that emerging market equities performed just as well as US markets between 2002 and 2021, and outperformed non-US developed markets. Emerging market bonds have also outperformed developed market bonds in most years since 2008.

Insurance companies, meanwhile, face a regulatory environment that discourages investments in higher-risk or less liquid assets, including EMDE infrastructure, even though these might be more profitable in the

long run. Regulations like the EU’s Solvency II impose capital charges disproportionate to the actual risks, leading to an unfair treatment of non-OECD infrastructure investment. Sustainable finance regulations, such as the EU’s green asset ratio, exclude sustainable investments outside the EU, further complicating the landscape.

With so much global growth shifting to EMDEs, private investors in developed markets are missing out on potentially lucrative returns, as well as the opportunity to invest in sustainable growth. Tackling regulatory and behavioural barriers in these private institutions could unlock the capital needed for a global green transition.

Samantha Attridge

Principal Research Fellow, ODI

London SE1, UK

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoIs sharing your smartphone PIN part of a healthy relationship?

-

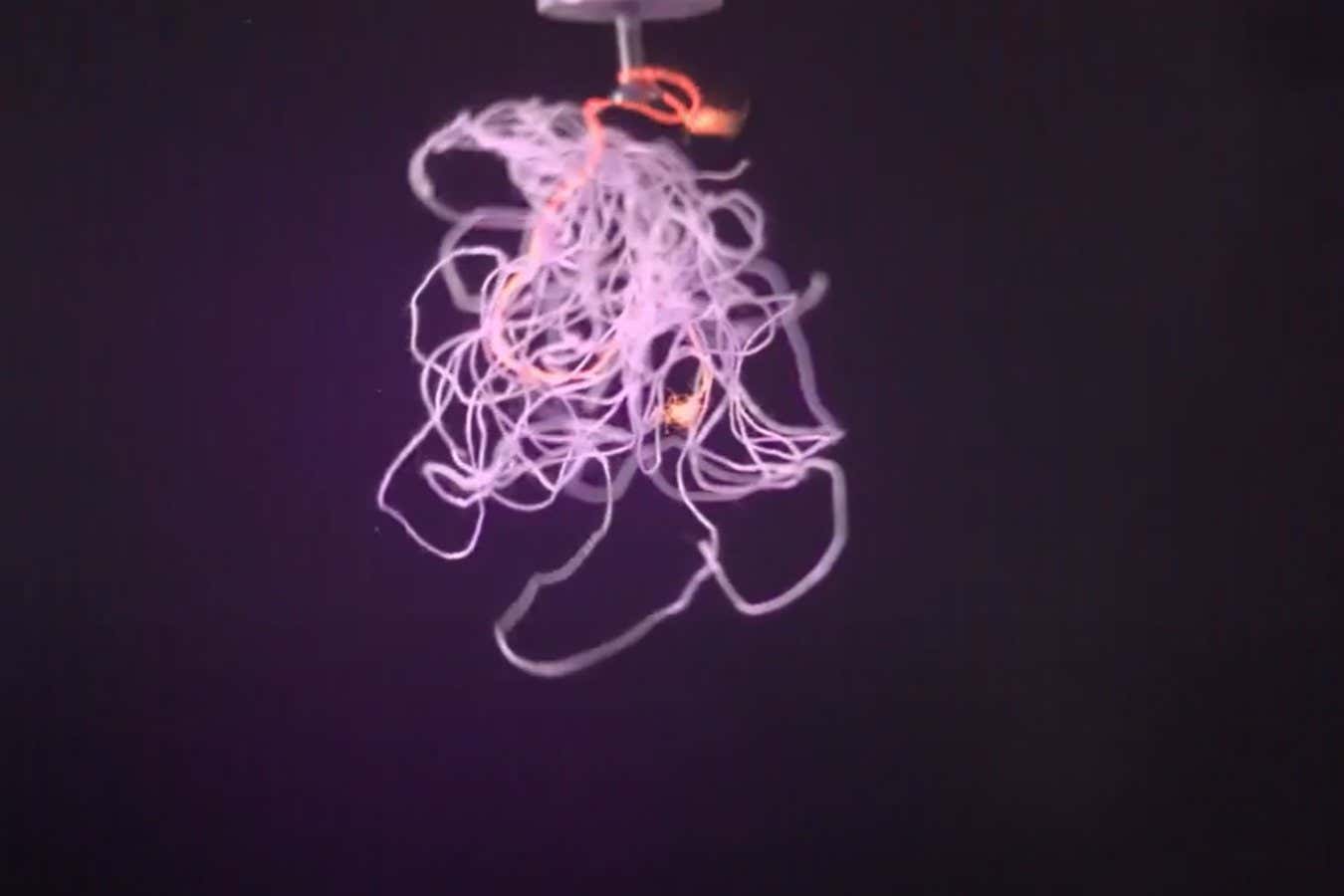

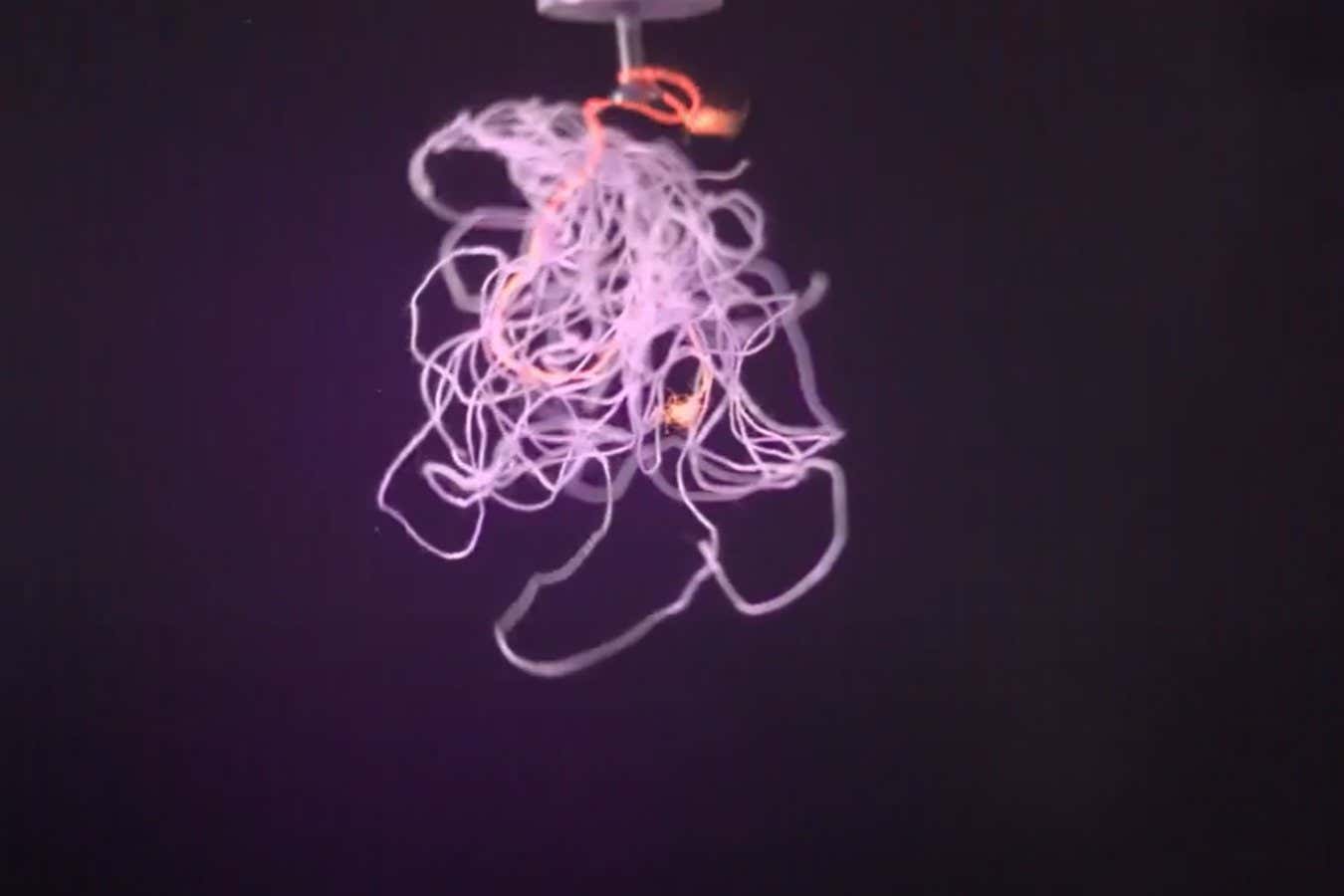

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoHow to unsnarl a tangle of threads, according to physics

-

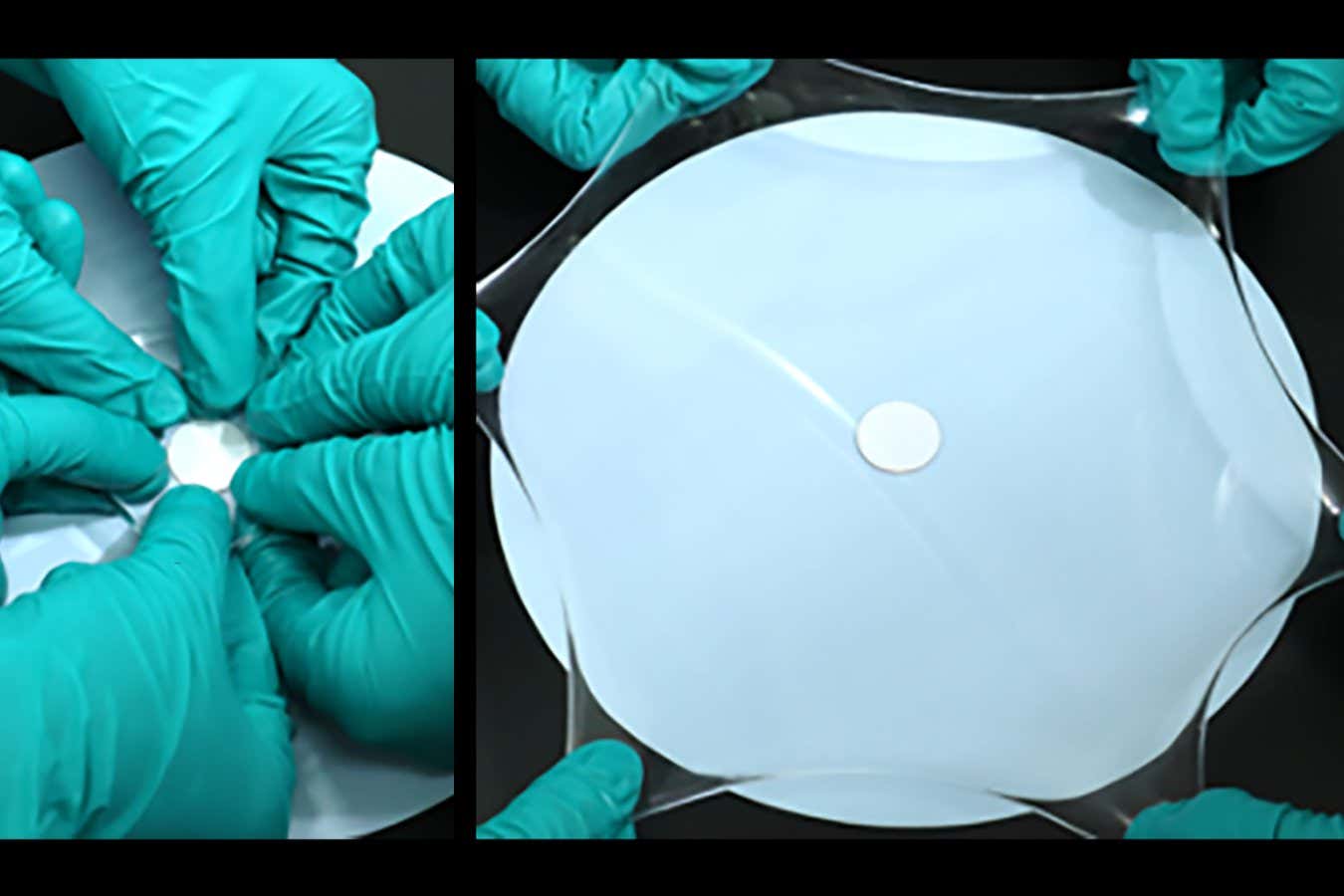

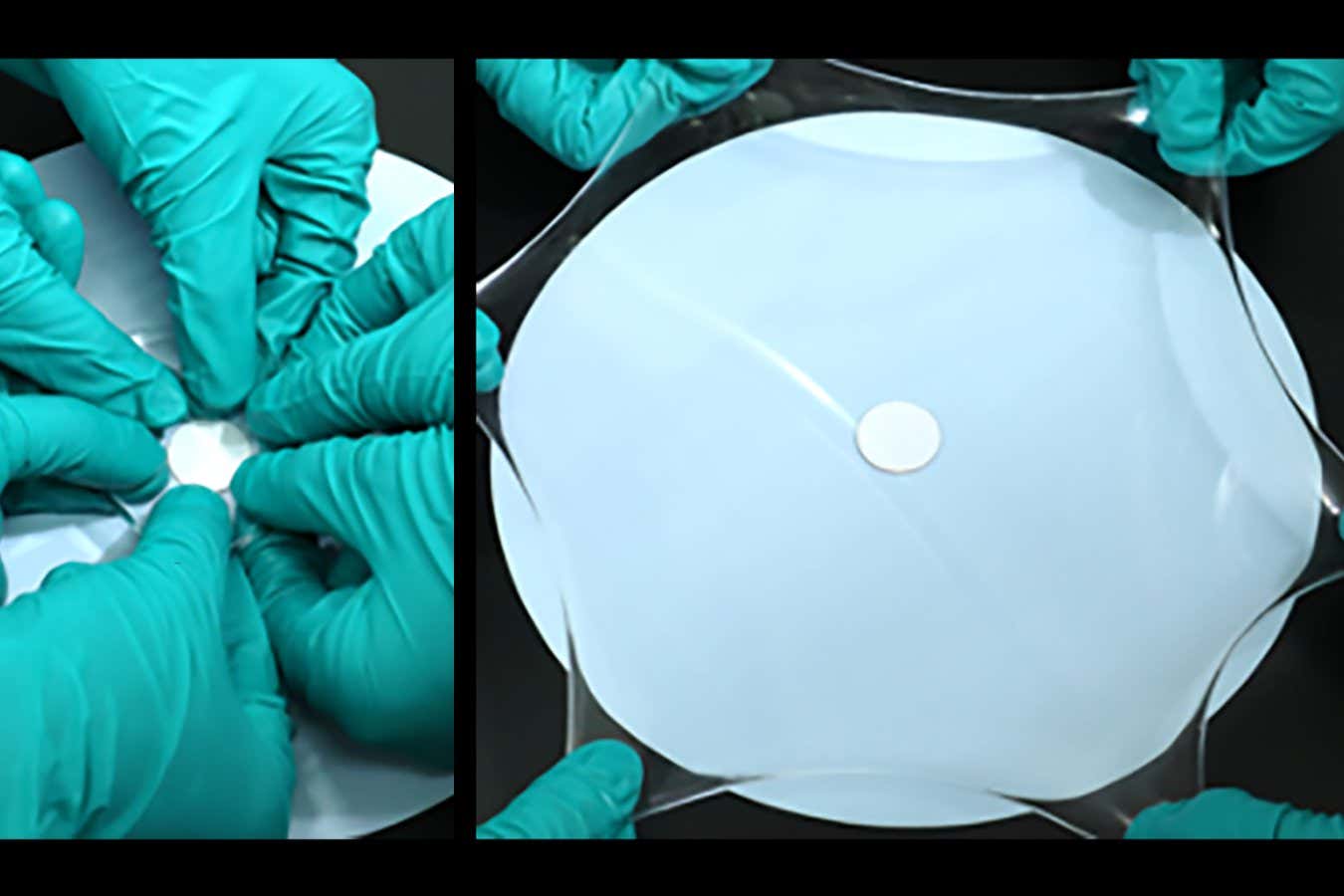

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoHyperelastic gel is one of the stretchiest materials known to science

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month ago‘Running of the bulls’ festival crowds move like charged particles

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoMaxwell’s demon charges quantum batteries inside of a quantum computer

-

Technology1 month ago

Technology1 month agoWould-be reality TV contestants ‘not looking real’

-

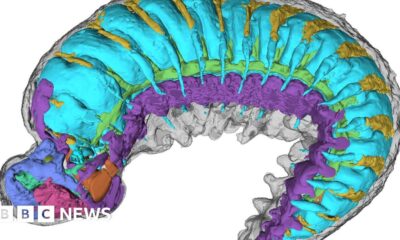

Science & Environment4 weeks ago

Science & Environment4 weeks agoX-rays reveal half-billion-year-old insect ancestor

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoSunlight-trapping device can generate temperatures over 1000°C

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoUkraine is using AI to manage the removal of Russian landmines

-

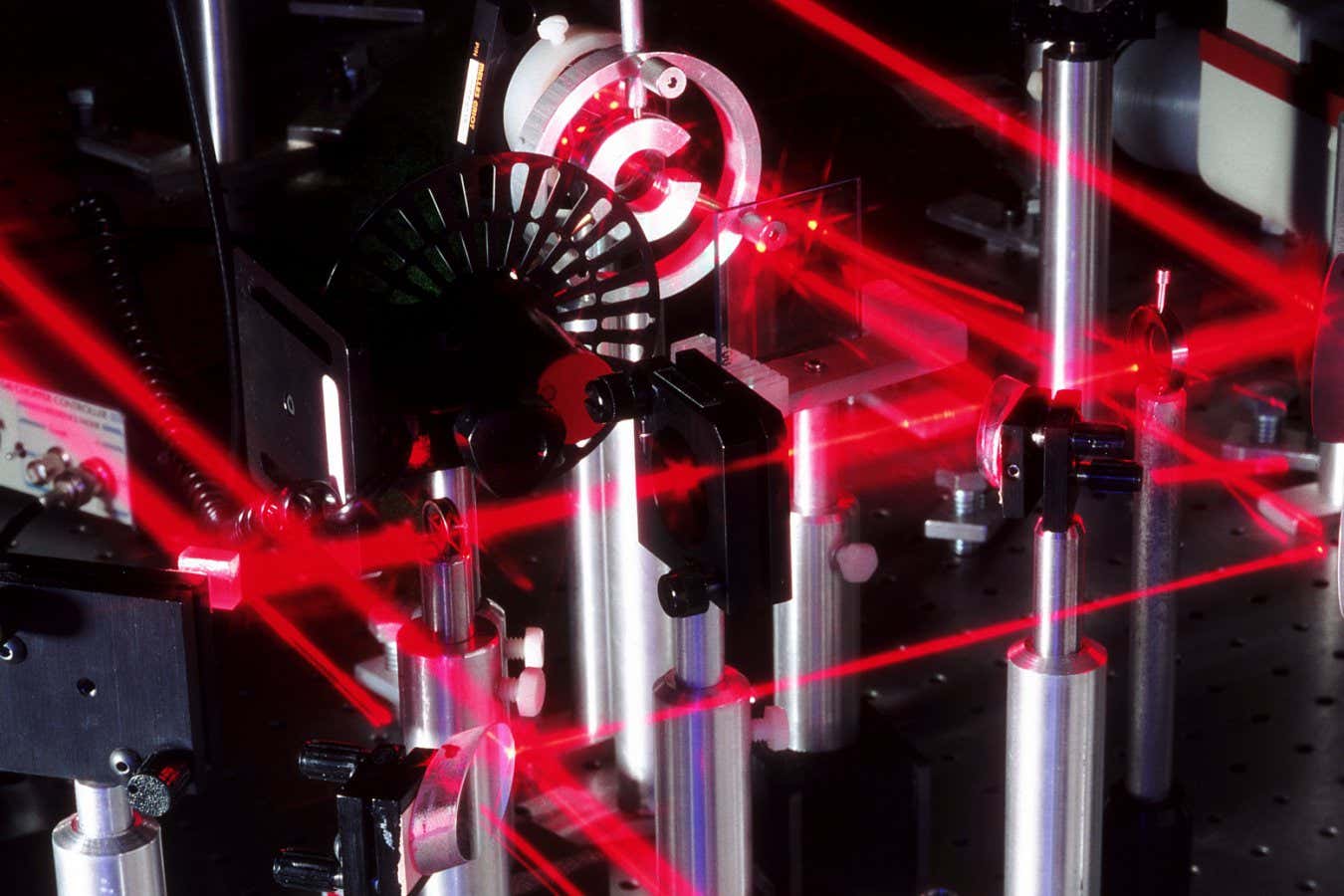

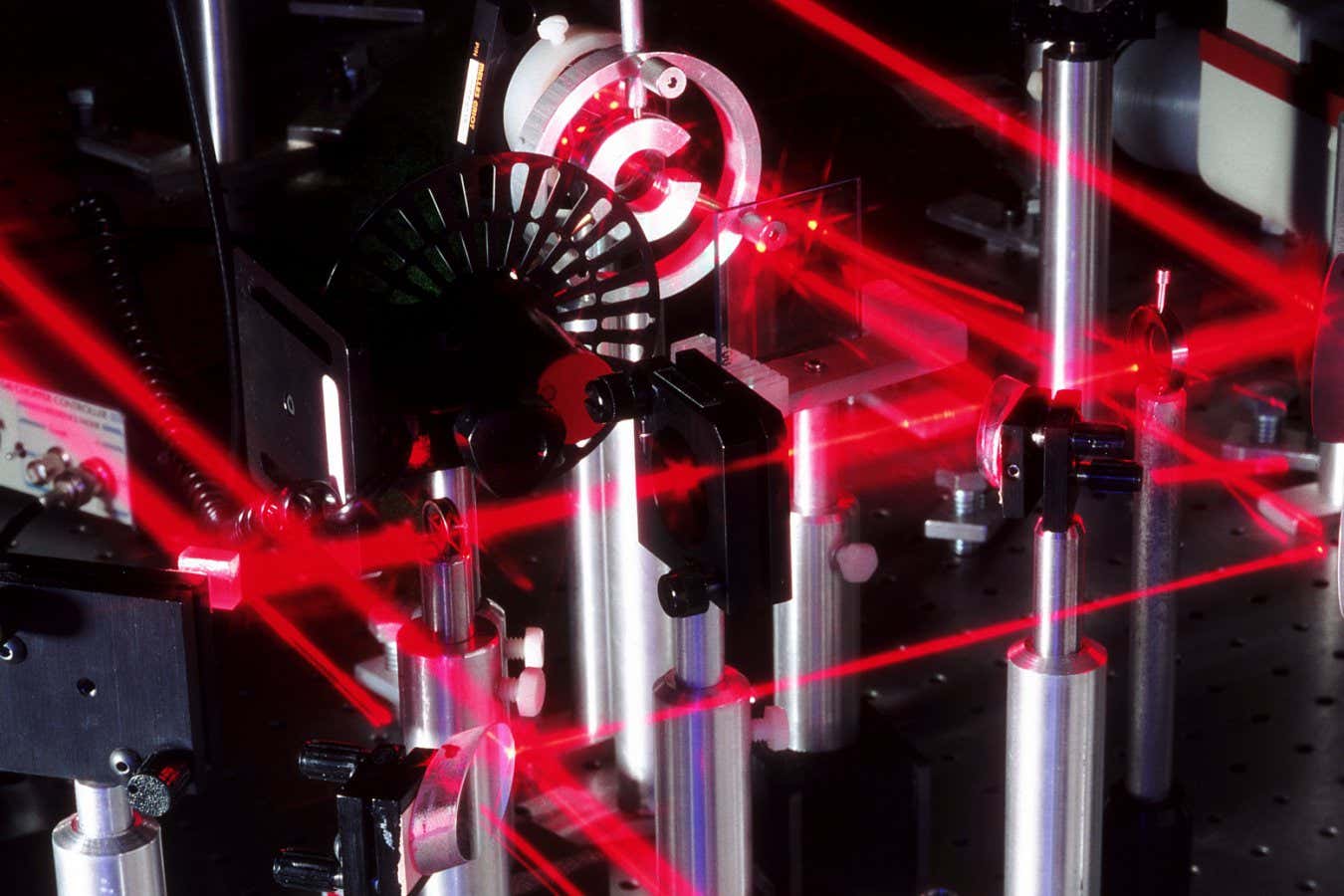

Science & Environment1 month ago

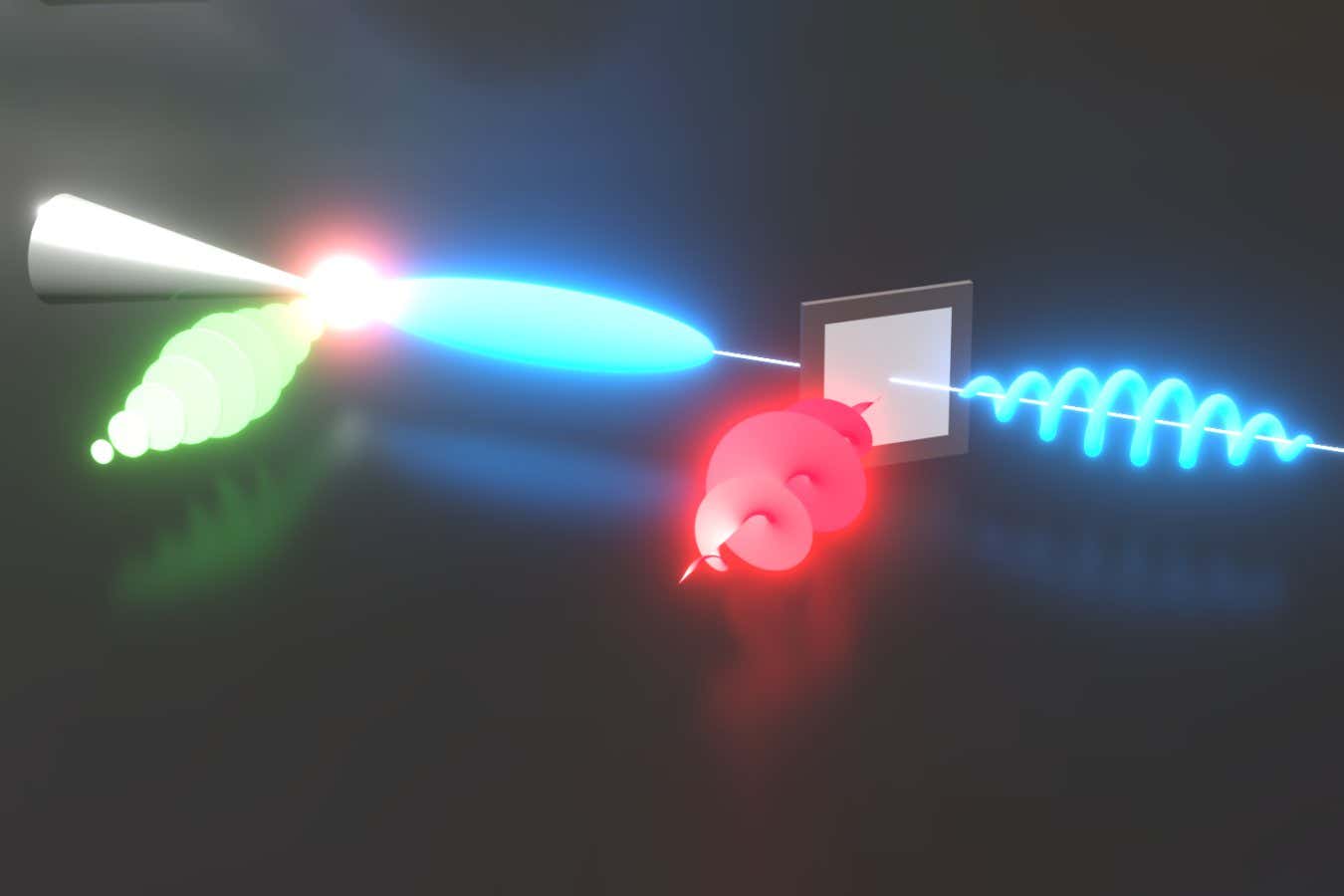

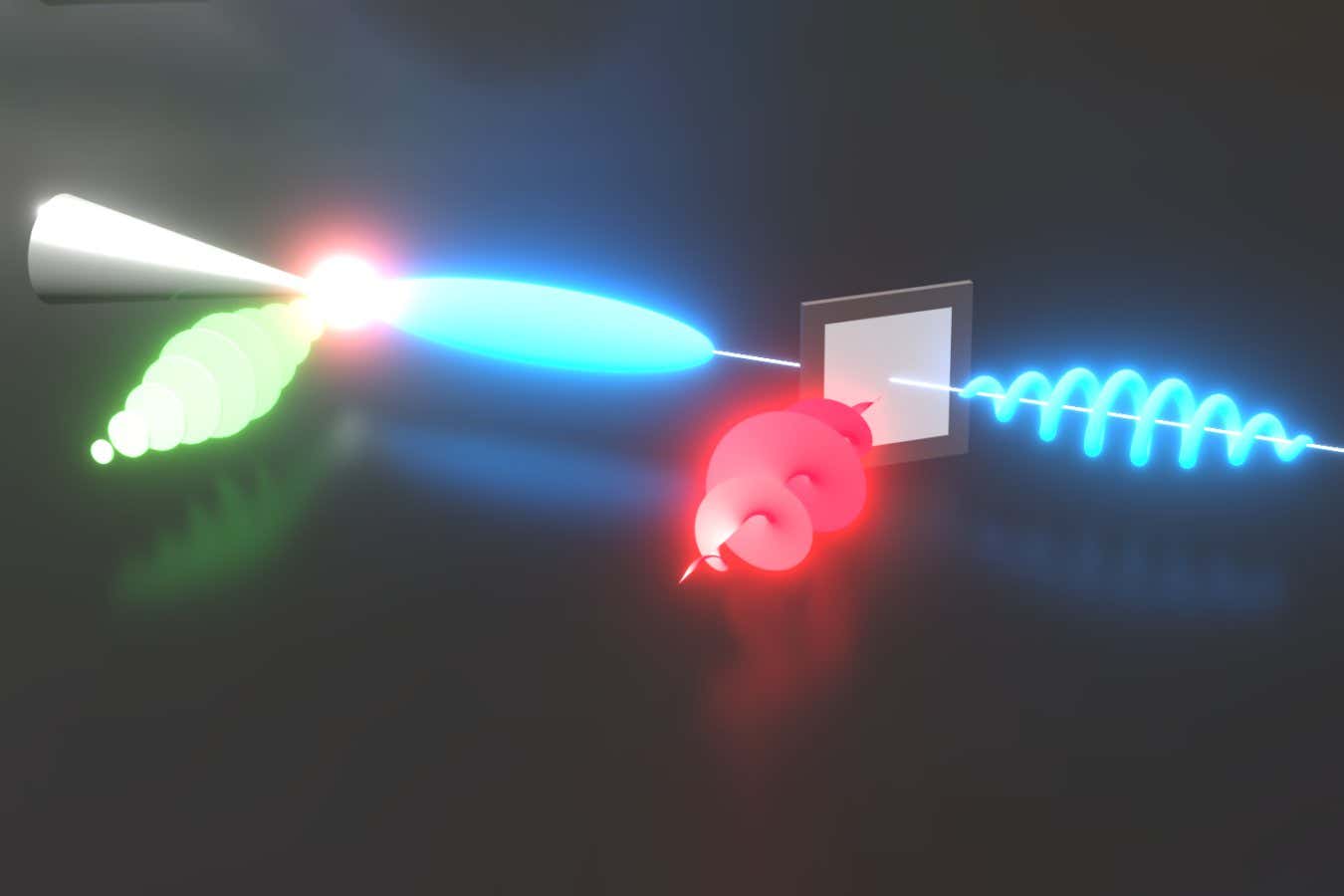

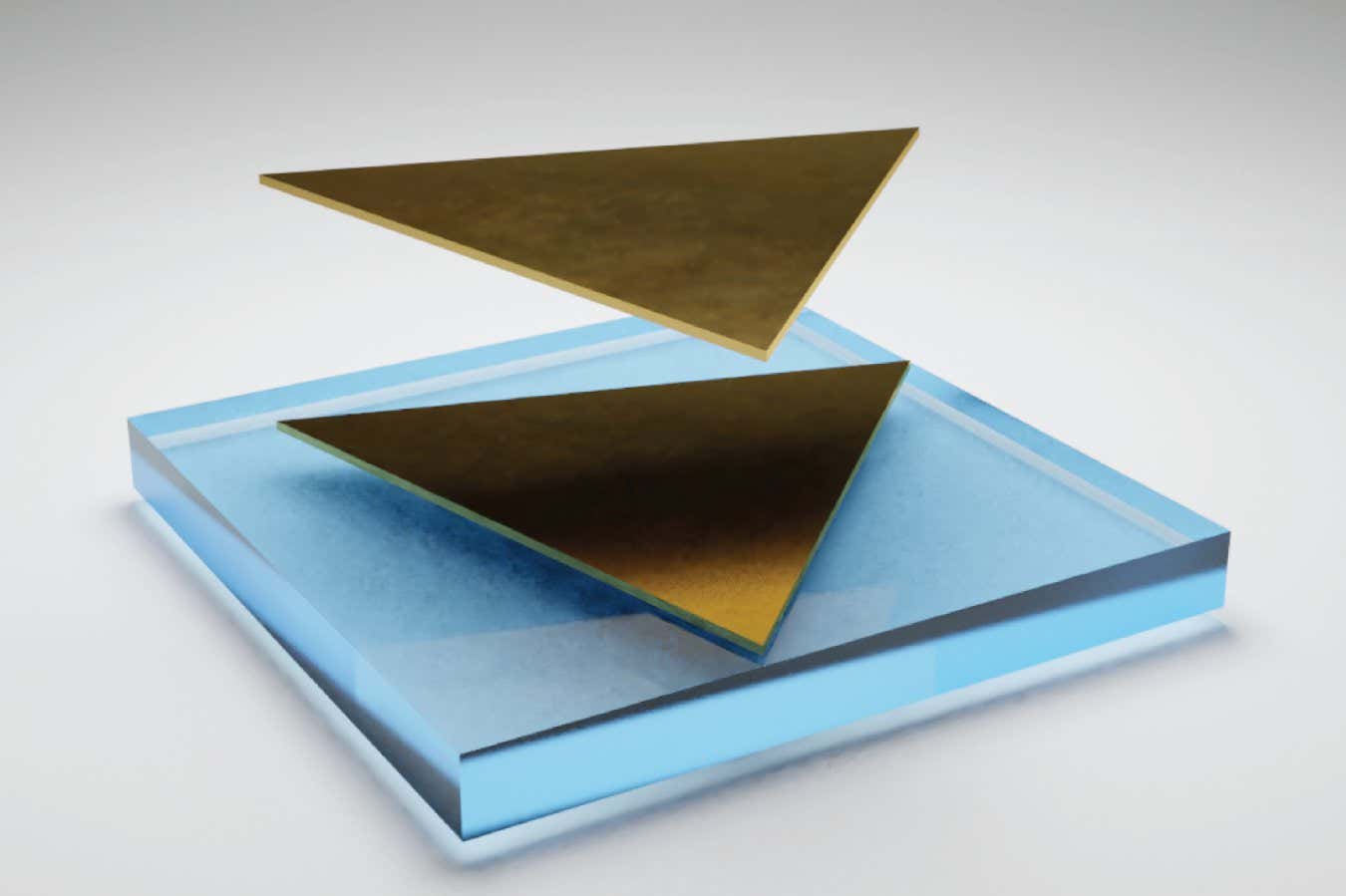

Science & Environment1 month agoLiquid crystals could improve quantum communication devices

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoQuantum ‘supersolid’ matter stirred using magnets

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoসারাদেশে দিনব্যাপী বৃষ্টির পূর্বাভাস; সমুদ্রবন্দরে ৩ নম্বর সংকেত | Weather Today | Jamuna TV

-

Football3 weeks ago

Football3 weeks agoRangers & Celtic ready for first SWPL derby showdown

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks ago▶ Hamas Spent $1B on Tunnels Instead of Investing in a Future for Gaza’s People

-

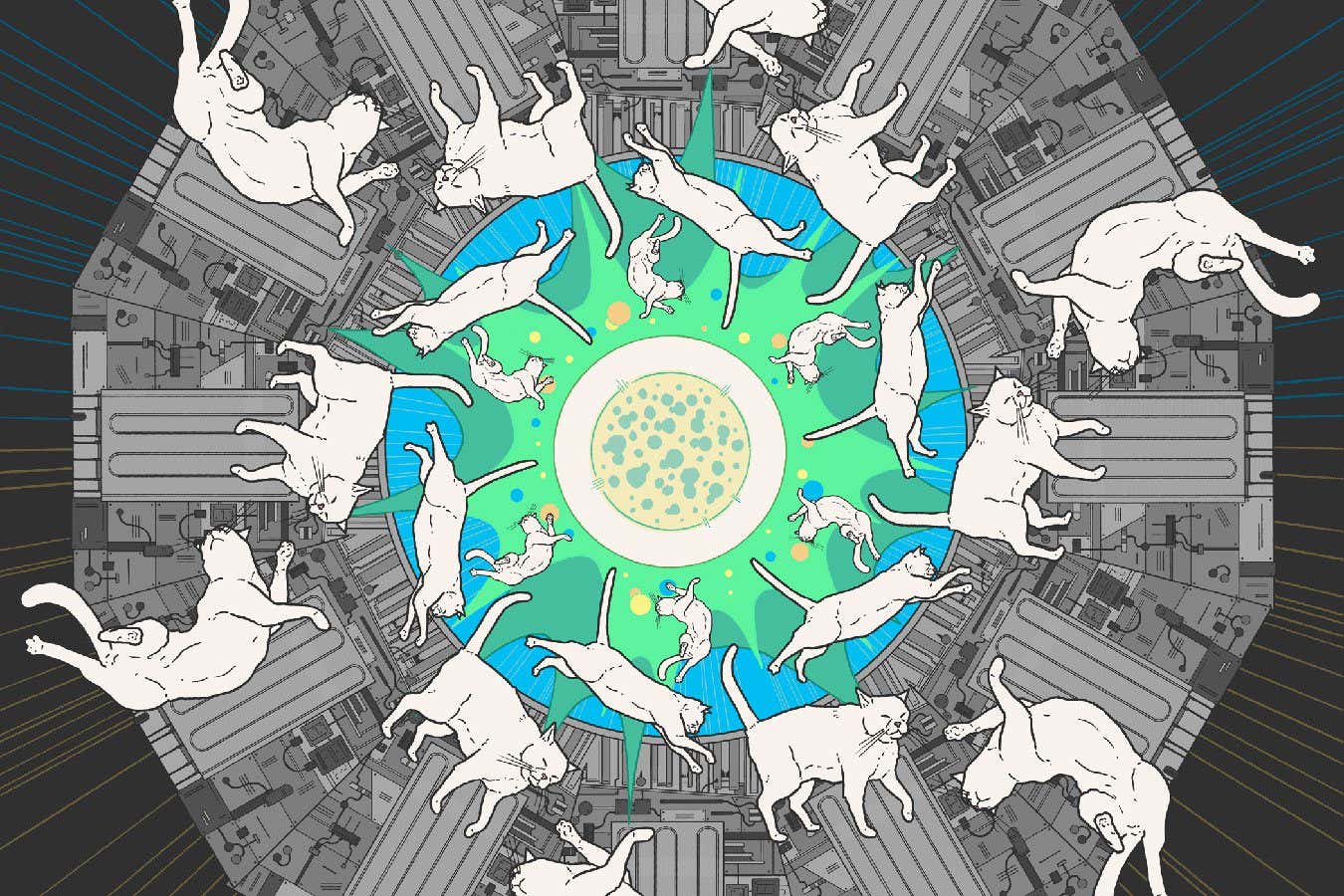

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoA new kind of experiment at the Large Hadron Collider could unravel quantum reality

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoLaser helps turn an electron into a coil of mass and charge

-

Womens Workouts1 month ago

Womens Workouts1 month ago3 Day Full Body Women’s Dumbbell Only Workout

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoSamsung Passkeys will work with Samsung’s smart home devices

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoMassive blasts in Beirut after renewed Israeli air strikes

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoWhen to tip and when not to tip

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks ago‘Uncrowned queen’ Kayla Harrison tastes blood, wants UFC title run

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoBoxing: World champion Nick Ball set for Liverpool homecoming against Ronny Rios

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoNavigating the News Void: Opportunities for Revitalization

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoMicrophone made of atom-thick graphene could be used in smartphones

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoMan City ask for Premier League season to be DELAYED as Pep Guardiola escalates fixture pile-up row

-

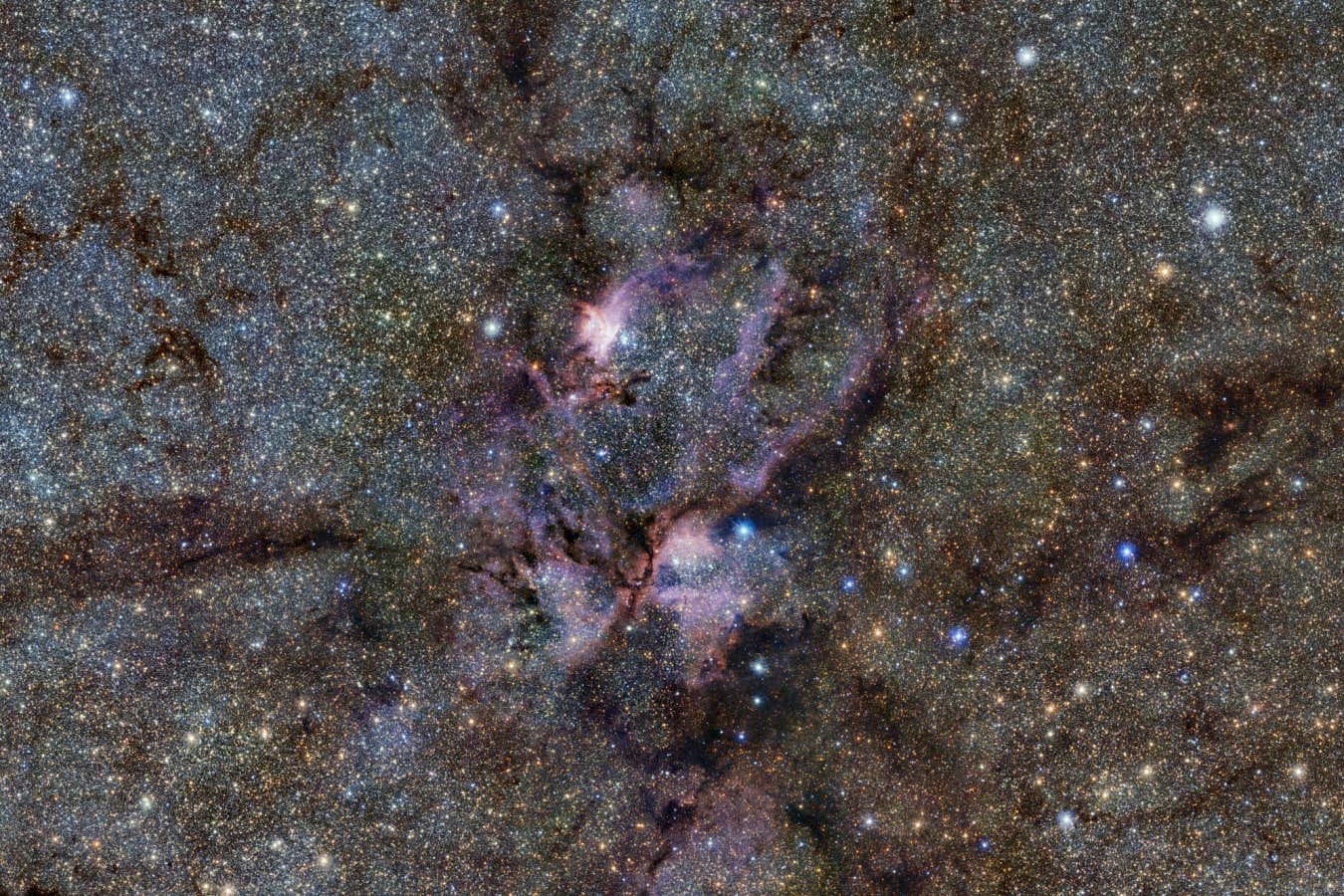

Science & Environment1 month ago

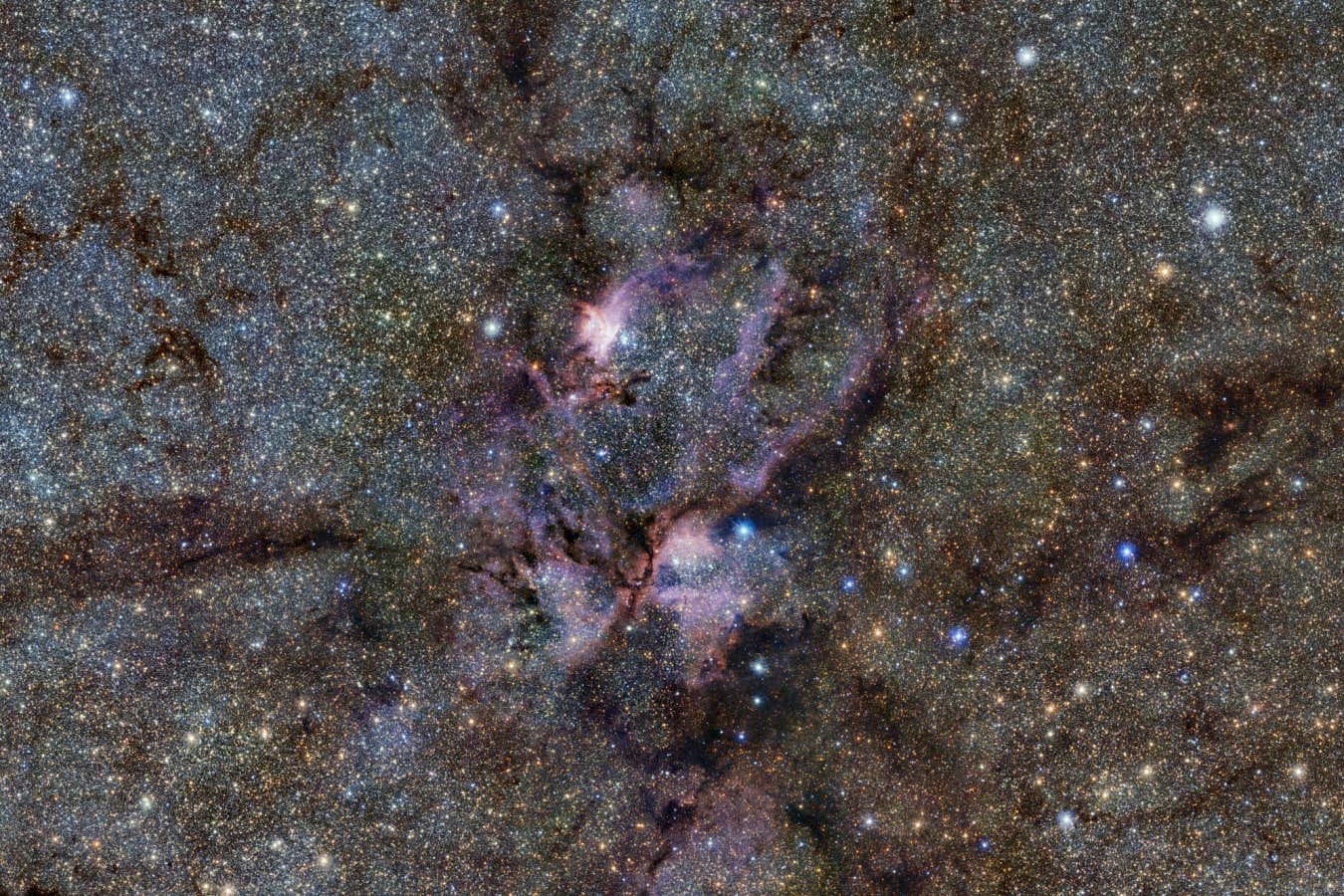

Science & Environment1 month agoWhy this is a golden age for life to thrive across the universe

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoPhysicists have worked out how to melt any material

-

Business3 weeks ago

DoJ accuses Donald Trump of ‘private criminal effort’ to overturn 2020 election

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoWales fall to second loss of WXV against Italy

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoPereira vs. Rountree prediction: Champ chases legend status

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks ago‘Blacks for Trump’ and Pennsylvania progressives play for undecided voters

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoQuantum forces used to automatically assemble tiny device

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoA slight curve helps rocks make the biggest splash

-

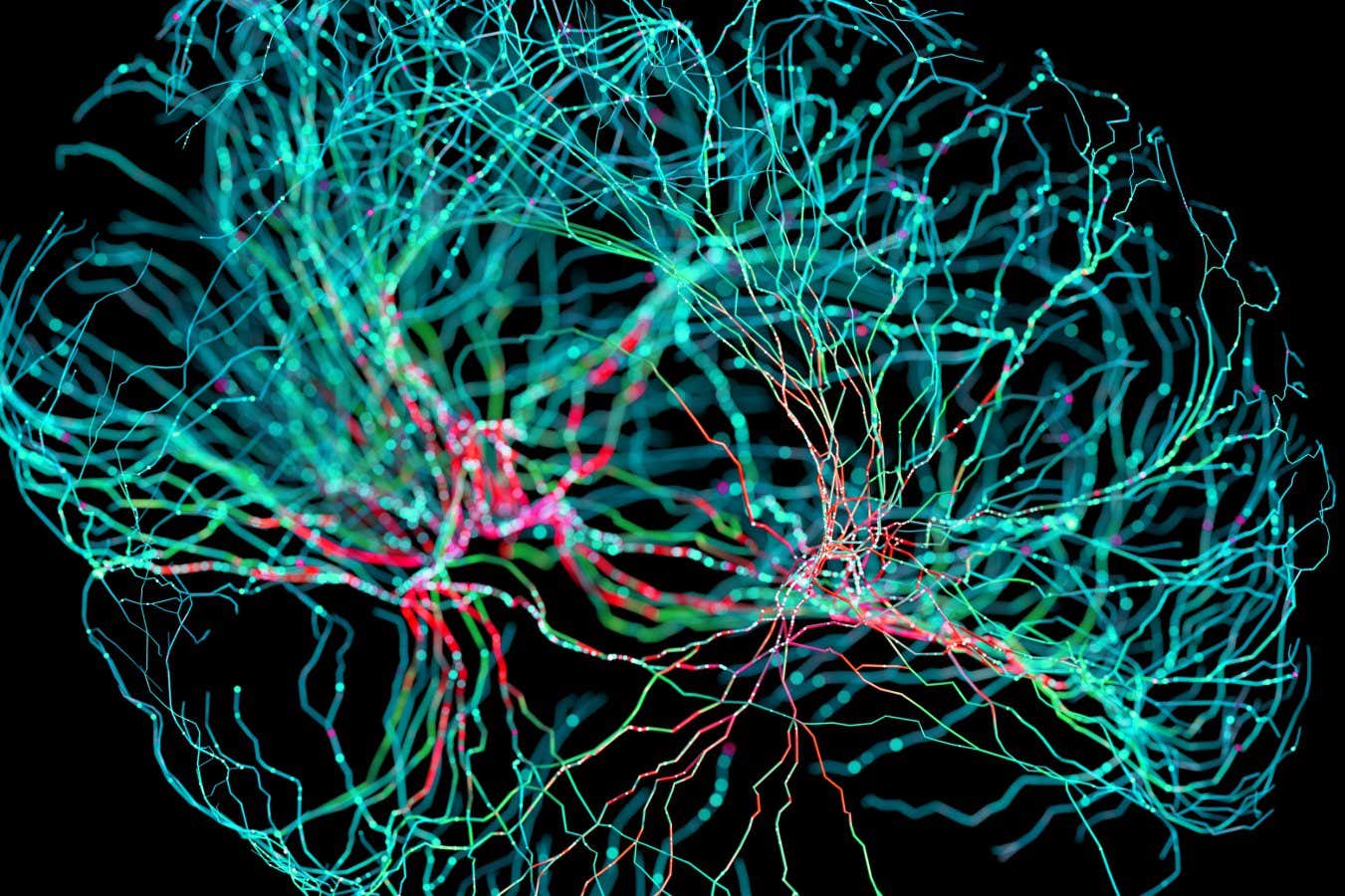

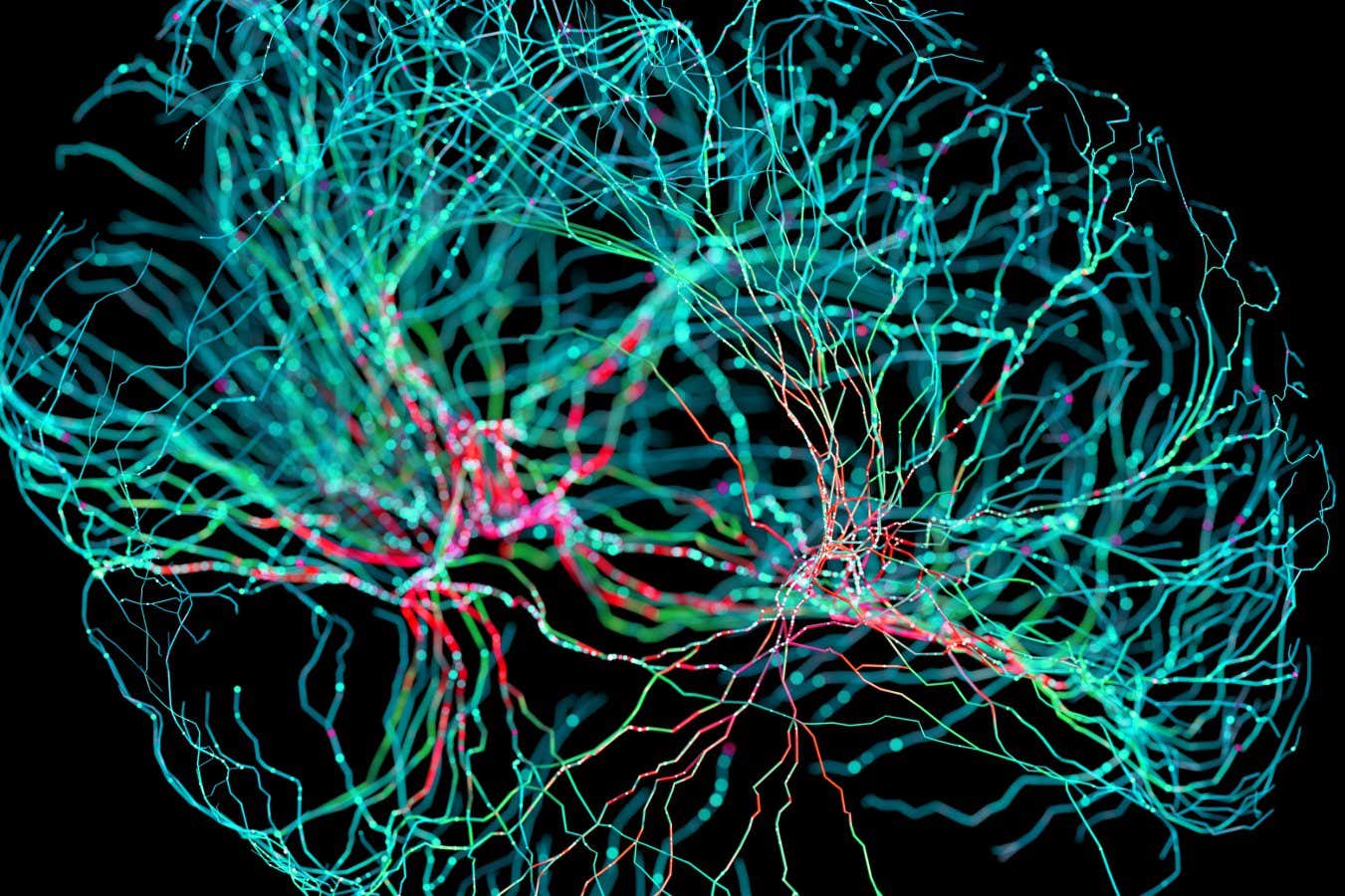

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoNerve fibres in the brain could generate quantum entanglement

-

News1 month ago

News1 month ago▶️ Hamas in the West Bank: Rising Support and Deadly Attacks You Might Not Know About

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoJulianna Peña trashes Raquel Pennington’s behavior as champ

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoDana White’s Contender Series 74 recap, analysis, winner grades

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoMusk faces SEC questions over X takeover

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoThis AI video generator can melt, crush, blow up, or turn anything into cake

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoSturm Graz: How Austrians ended Red Bull’s title dominance

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoFamily plans to honor hurricane victim using logs from fallen tree that killed him

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoAaron Ramsdale: Southampton goalkeeper left Arsenal for more game time

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoHow to wrap your mind around the real multiverse

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoNuclear fusion experiment overcomes two key operating hurdles

-

Technology1 month ago

Technology1 month agoMeta has a major opportunity to win the AI hardware race

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoWhy Machines Learn: A clever primer makes sense of what makes AI possible

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoRussia is building ground-based kamikaze robots out of old hoverboards

-

News1 month ago

News1 month ago▶️ Media Bias: How They Spin Attack on Hezbollah and Ignore the Reality

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoITER: Is the world’s biggest fusion experiment dead after new delay to 2035?

-

Football3 weeks ago

Football3 weeks agoWhy does Prince William support Aston Villa?

-

Business3 weeks ago

Sterling slides after Bailey says BoE could be ‘a bit more aggressive’ on rates

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoMicrosoft just dropped Drasi, and it could change how we handle big data

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoChina Open: Carlos Alcaraz recovers to beat Jannik Sinner in dramatic final

-

Money3 weeks ago

Money3 weeks agoWetherspoons issues update on closures – see the full list of five still at risk and 26 gone for good

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks agoCoco Gauff stages superb comeback to reach China Open final

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoTime travel sci-fi novel is a rip-roaringly good thought experiment

-

Sport4 weeks ago

Sport4 weeks agoWorld’s sexiest referee Claudia Romani shows off incredible figure in animal print bikini on South Beach

-

Business3 weeks ago

Bank of England warns of ‘future stress’ from hedge fund bets against US Treasuries

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoChancellor Rachel Reeves says she needs to raise £20bn. How might she do it?

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoGmail gets redesigned summary cards with more data & features

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoTexas is suing TikTok for allegedly violating its new child privacy law

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoThe best budget robot vacuums for 2024

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoPereira vs. Rountree preview show live stream

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoThe best shows on Max (formerly HBO Max) right now

-

Sport3 weeks ago

Sport3 weeks ago2024 ICC Women’s T20 World Cup: Pakistan beat Sri Lanka

-

Entertainment3 weeks ago

Entertainment3 weeks agoNew documentary explores actor Christopher Reeve’s life and legacy

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoAlex Pereira faces ‘trap game’ vs. Khalil Rountree

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoWoman who died of cancer ‘was misdiagnosed on phone call with GP’

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoGerman Car Company Declares Bankruptcy – 200 Employees Lose Their Jobs

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks ago‘I was fighting on automatic pilot’ at UFC 306

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoKetlen Vieira vs. Kayla Harrison pick, start time, odds: UFC 307

-

News1 month ago

the pick of new debut fiction

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoOur millionaire neighbour blocks us from using public footpath & screams at us in street.. it’s like living in a WARZONE – WordupNews

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoEpic Games CEO Tim Sweeney renews blast at ‘gatekeeper’ platform owners

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoHull KR 10-8 Warrington Wolves – Robins reach first Super League Grand Final

-

MMA3 weeks ago

MMA3 weeks agoUFC 307 preview show: Will Alex Pereira’s wild ride continue, or does Khalil Rountree shock the world?

-

Business3 weeks ago

Business3 weeks agoStark difference in UK and Ireland’s budgets

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoBalancing India and China Is the Challenge for Sri Lanka’s Dissanayake

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoHeavy strikes shake Beirut as Israel expands Lebanon campaign

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoLove Island star sparks feud rumours as one Islander is missing from glam girls’ night

-

Football3 weeks ago

Football3 weeks agoSimo Valakari: New St Johnstone boss says Scotland special in his heart

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoJ.B. Hunt and UP.Labs launch venture lab to build logistics startups

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoPhillip Schofield accidentally sets his camp on FIRE after using emergency radio to Channel 5 crew

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoOpenAI secured more billions, but there’s still capital left for other startups

-

Business3 weeks ago

Head of UK Competition Appeal Tribunal to step down after rebuke for serious misconduct

-

Business3 weeks ago

The search for Japan’s ‘lost’ art

-

Science & Environment3 weeks ago

Science & Environment3 weeks agoMarkets watch for dangers of further escalation

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoHeartbreaking end to search as body of influencer, 27, found after yacht party shipwreck on ‘Devil’s Throat’ coastline

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoApple iPhone 16 Plus vs Samsung Galaxy S24+

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoPopular financial newsletter claims Roblox enables child sexual abuse

-

Health & fitness3 weeks ago

Health & fitness3 weeks agoNHS surgeon who couldn’t find his scalpel cut patient’s chest open with the penknife he used to slice up his lunch

-

Money3 weeks ago

Money3 weeks agoPub selling Britain’s ‘CHEAPEST’ pints for just £2.60 – but you’ll have to follow super-strict rules to get in

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoIf you’ve ever considered smart glasses, this Amazon deal is for you

-

News3 weeks ago

News3 weeks agoLiverpool secure win over Bologna on a night that shows this format might work

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoAmazon’s Ring just doubled the price of its alarm monitoring service for grandfathered customers

-

TV3 weeks ago

TV3 weeks agoMaayavi (මායාවී) | Episode 23 | 02nd October 2024 | Sirasa TV

-

Politics3 weeks ago

Rosie Duffield’s savage departure raises difficult questions for Keir Starmer. He’d be foolish to ignore them | Gaby Hinsliff

-

Business3 weeks ago

Can liberals be trusted with liberalism?

-

Technology3 weeks ago

Technology3 weeks agoA very underrated horror movie sequel is streaming on Max

-

Science & Environment1 month ago

Science & Environment1 month agoPhysicists are grappling with their own reproducibility crisis

You must be logged in to post a comment Login