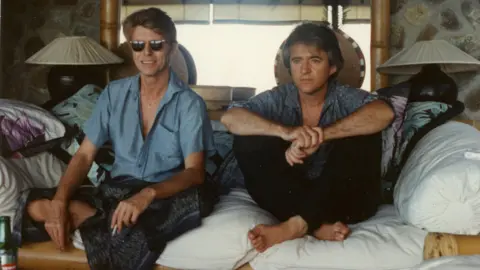

The pleasures of writer-director Jon Watts’ crime caper Wolfs are numerous: George Clooney and Brad Pitt play dueling fixers called in to clean up the accidental death of a young, adorable student—prior to his demise, occasioned by his jumping on a hotel bed, he’d been picked up by high-powered district attorney Amy Ryan in a bar. Clooney and Pitt have reached the age where they know it’s useless to pretend they’re something they’re not. Their faces look handsomely lived in; the whispers of gray in their artfully sculpted chin stubble feel honest and earned. Like Lucy and Ethel in the throes of a falling out, they’re fun to watch as they bicker and crab at one another, leaning heavily on their silver-fox charm. Still, what they’re offering feels as comfy as the worn-in leather jackets they wear. And in this late-2024 movie season, if you find yourself wishing for something more—for another view of what actors in the 50-to-60-ish age bracket can do—look to the women, who insist on pushing themselves out of the comfort zone rather than settling into it.

Demi Moore in Coralie Fargeat’s horror-of-aging black comedy The Substance, Nicole Kidman in Halina Reijn’s May-December sizzler Babygirl, Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore in Pedro Almodóvar’s moving and provocative The Room Next Door: These big-name movie stars are pushing into new territory rather than just riffing on whatever may have made them appealing 10, 20, or 30 years ago. That’s a luxury no actress can afford, and these women know it.

Like lots of us, I will always love looking at guys: that includes Clooney and Pitt in Wolfs, both of whom are settling nicely into perfectly age-appropriate handsomeness. But as I watched Clooney’s character drive around nighttime New York with the silky strains of Sade’s 1980s hit “Smooth Operator” floating from his car stereo, it occurred to me that guys can afford nostalgia; women need to be modern every minute, or they risk being left behind. I also realized that months after first seeing Moore’s performance in The Substance—a movie that isn’t, overall, even very good—I’m still thinking about the shaky limb she crawled onto. There are no shaky limbs in Wolfs, though there are some creaky joints, and an Advil joke—because aches and pains are a thing men can joke about, charmingly, while women who do the same run the risk of coming off as crotchety old complainers.

Read more: The 33 Most Anticipated Movies of Fall 2024

In The Substance, Moore plays Elisabeth Sparkle, an aging movie star who—like Moore herself—has kept herself in fabulous shape. She’s also doing more than OK, hosting a popular 1980s-style exercise show. But she gets the sense that her boss, a leering Dennis Quaid, is looking to replace her with a younger model. Then she catches wind of a revolutionary new injectable known as The Substance, which stimulates the creation of a younger, and supposedly in all ways better, clone. The trick is that the original and the clone must switch roles every seven days, without exception, via some sort of mystery infusion. Elisabeth can’t resist giving The Substance a try, though she’s not prepared for how much she comes to resent her youthful, nubile clone, played by a vapidly effervescent Margaret Qualley.

The Substance devolves into a senseless jumble of body horror that panders to its audience rather than challenging it. Even so, Moore’s performance is naked and fearless in all ways. The years from 50 to 60 can feel perilous for women: men in that age bracket are often (though not always) viewed as more powerful and sexy than ever. Women can feel that way too, but the radical hormonal adjustments that hit during that period—amidst other challenges that might include raising kids, a marital breakup, or striving to remain relevant in the workplace—usually mean they have to fight harder for their confidence. In The Substance, we see Moore fighting that battle and looking great—but when her sense of self-esteem flags, as it does while she’s getting ready for a date with a nice guy, an old schoolmate who’s asked her out, we see how easily those undermining inner voices can triumph over us. At first, she looks at herself in the mirror and likes what she sees: she’s put on an amazing red going-out dress that looks sexy without trying too hard. But she can’t help comparing her fifty-something self to the younger Qualley version. She redoes—and in the process overdoes—her makeup. She wraps a massive scarf around her neck, clearly obsessed with wrinkled skin that only she can see. Moore turns Elisabeth’s increasing desperation into a hamster-wheel frenzy, and though she plays it for laughs, not pathos, you feel its power over her. In the end, Elisabeth spends so much time fussing with her appearance that she misses her date. It’s the finest, subtlest scene in a movie that’s largely a mess—but Moore gives it her all.

It’s true, too, that all actors in their 50s and beyond pour a great deal of effort and money into preserving their good looks. We know that Clooney and Pitt surely benefit from, at the very least, the best skin care money can buy. But one of the unfair double standards of biology is that men often look better when they’re a little weatherbeaten; unless women fix up in some way, even if that just means moisturizer, concealer, and lipstick, they often end up fielding backhanded noncompliments like “You look tired.” You can argue that we shouldn’t care at all—of course, we shouldn’t. But to some degree, most of us do, and you can’t blame actresses, whose faces are subject to constant scrutiny, for caring even more.

In Babygirl—which opens in the States on Christmas Day—Nicole Kidman plays Romy, a married past-middle-aged executive who becomes involved with a much younger intern, played by Harris Dickinson. He doesn’t gaze into her soul so much as stare right into the heart of her unspoken sexual desires—he’s got a kind of intuitive erotic clairvoyance. This both rattles and thrills her; his attentions become a drug she can’t kick. All the while, of course, you’re looking at Kidman, with her marble visage, and thinking, Well, thanks to any combination of money, cosmetic intervention, time at the gym, and good genes, she’s perfectly gorgeous. Why wouldn’t any character she plays land the hot young guy?

But that line of thinking misses the point. Kidman plays Romy’s fears and insecurities as free-floating, all-powerful forces that are divorced from how great she looks. Though beauty and money may make life easier, they can’t solve every problem, and an expectation of happiness is often the very thing that kills its possibility. Kidman’s performance in Babygirl shows that principle in action. Romy has no reason to believe that her handsome, attentive, theater-director husband (played by Antonio Banderas) shouldn’t automatically make her happy. So why is she miserable? People often act surprised when Kidman gives a fearless performance—how quickly we forget that, in Lee Daniel’s The Paperboy, she once peed on a jellyfish-stung Zac Efron. But that may be one of her secret gifts: her ladylike façade is a shell that she herself cracks again and again, and somehow, we’re always surprised by what she chooses to reveal.

Read more: 15 of the Sexiest Movies You’ve (Probably) Never Seen

Admittedly, we tend to reflexively lament the lack of serious roles for “older” actresses, though in a perfect world, those actresses would be able to make their share of old-school crime capers, as the boys do. Now and then we get one, a la Ocean’s 8, though most of our so-called serious actresses (even when they’re great at getting laughs, as Meryl Streep has always been) tend to put comedy on the back burner until their golden years. It’s our over-70 actresses—Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, Diane Keaton—who seem to be having more fun with that genre. Maybe that’s because those actresses are long past the point of having to prove themselves. And performers in their fifties, particularly but not only women, may still feel they have so much to prove.

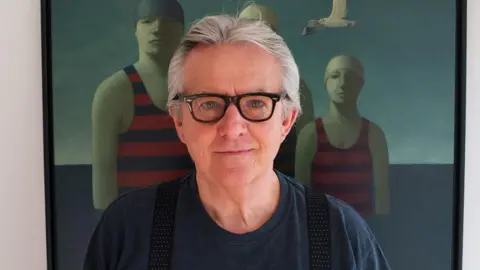

Even so, there’s pleasure to be found even in the most serious subjects. Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door—opening in the States in late December—is adapted from a 2020 Sigrid Nunez novel, What Are You Going Through, and stars Tilda Swinton as Martha, a woman suffering from terminal cancer who enlists a long-lost friend, Julianne Moore’s Ingrid, to help her die on her own terms. That sounds like a downer if ever there were one. But if Almodóvar is sometimes a serious director, he’s never a morose one—there are always strata of joyousness in his movies, and The Room Next Door is no exception.

Moore’s Ingrid is a mildly high-strung writer; at first, she balks at taking on the responsibility of helping her friend with this seemingly unsavory task. But as the two women spend more time together, she frees herself of the gravity of this mission and comes to see it as a way of helping Martha take flight. Swinton’s Martha, an accomplished war correspondent who has also raised a daughter on her own, moves through the movie like an Earthling who’s been in space for a long time, only just now realizing what it means to truly touch ground—she’s like a version of Bowie’s homesick alien in The Man Who Fell to Earth, though the home she’s moving toward is a truly final resting place.

Yet this last leg of her journey—one that Ingrid, with all her fluttery-butterfly energy, will partly share with her—isn’t an inconsequential one. She’s stepping out of own adventure and into another, and because this is Tilda Swinton, she looks great doing so: even as her illness takes its toll, she wraps herself—with the help of Almodóvar’s magic wand of color—in rainbow hues that reinforce all the possibilities of life. Maybe this movie is a caper, of sorts, though it’s a caper with a capper. No one gets out of this world alive. The entreaty of The Room Next Door is to use every second wisely, and to help others as best you can. That’s a lot for a movie, and a duo of actresses, to carry. But these two pull it off, literally, with flying colors.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login