NewsBeat

Family courts get new guidance on ‘parental alienation’ in family court battles

Family courts in England and Wales should give more weight to allegations of domestic abuse than to claims of “parental alienation”, according to new guidance.

When parents have separated, and are arguing over their children, they turn to the family court. In these private law children cases claim and counter-claim are common.

One parent, usually the mother, may accuse the other parent of abuse. The father may counter that she has manipulated the children against him – termed parental alienation.

How the court responds can have lifelong consequences for the family, as the judge has to decide whom the children live with, and what time they spend with the other parent.

Wednesday’s report from the advisory Family Justice Council says “despite the lack of research evidence, and international condemnation, reference is still made to the discredited concept of ‘parental alienation syndrome’.”

This is the idea that children show a recognisable pattern of behaviours if they have been manipulated by one parent against the other.

The guidance describes this as a “harmful pseudo science”.

It says there are genuine cases where alienating behaviours “impact” a child’s relationship with the other parent, but they are “relatively rare”.

According to research, over half of all private law cases involving children include allegations of domestic abuse.

It is not known how many include parental alienation, though judges have observed a rise in their own cases.

The guidance says “allegations of domestic abuse and ‘parental alienation’ cannot be equated” – pointing out that domestic abuse is a crime.

It is increasingly common for the parent accused of abuse, usually the father, to respond by claiming that the mother has turned the children against them.

These cases can drag out for many years, as the relationship between parents deteriorate, and children are affected.

Some come to court multiple times.

Where there is a claim of parental alienation psychologists can become involved, and their evidence is often influential.

In a case heard by the High Court late last year, Judge Mrs Justice Judd presided over a case involving two parents who had separated in 2017.

The mother told the family court then the father had abused her, and was granted a non-molestation order – injunctions used in urgent abuse cases.

The father had the right to contact with the children, supervised at first, but three years later, the father came to court saying contact between him and the children had broken down.

A psychologist, Melanie Gill, was asked to provide a “global assessment” of the family, which she filed in 2022.

She said the mother had unconsciously turned the two secondary school-age children against their father, something which the father seized on.

The mother was very worried she would lose her children, as she told The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, though she did win her case.

The new guidance says it is “inappropriate” for an expert to determine whether parental alienation has taken place.

It says that is for the court to decide, and a psychologist may be brought in later to advise how it should be dealt with.

The council also says that when a child rejects a parent, that is not enough to determine alienation.

The court has to examine whether that rejection is justified, perhaps by the parent’s own behaviour. And there must be evidence of manipulation.

The Family Justice Council is largely made up of senior judges and lawyers. Their guidance has been welcomed by some lawyers and charities.

Lucy Reed KC, founder of the Transparency Project – a charity that aims to explain family law – said it would have a major impact, making it much harder to prove “alienating behaviour”.

She said it would help courts to identify cases where allegations were being used as a litigation tactic, or as a means of silencing domestic abuse survivors.

Charlotte Proudman, who has represented many parents accused of parental alienation, said it was a “great step forward”.

The charity Women’s Aid said it was “a positive step in the right direction”.

However it said the guidance should be more child-centred, saying it was “concerning” that there was no reference to child sexual abuse.

Sam Morfey of the charity Both Parents Matter, formerly Families Need Fathers, said they welcomed the guidance, but added there was a need for recognition that “unfounded claims of abuse… can be evidence of alienation and a deliberate attempt to damage a child-parent relationship”.

NewsBeat

Israeli military building in Syria buffer zone, satellite image shows

BBC Verify

BBC / Planet Lab PBC

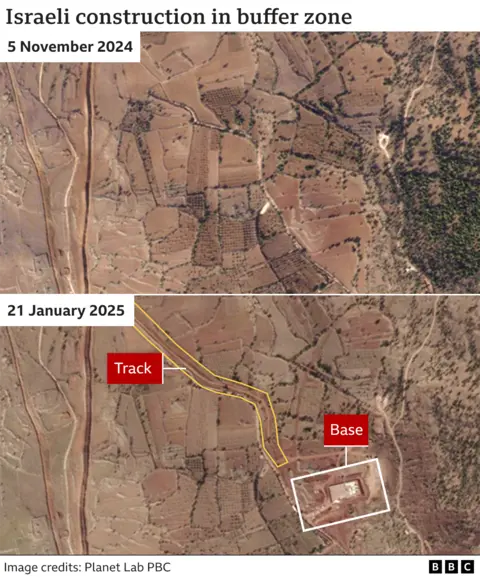

BBC / Planet Lab PBCNewly released satellite imagery shows Israel Defense Force construction taking place within the demilitarised buffer zone that separates it from Syria.

The image, obtained exclusively by BBC Verify, shows building work taking place at a location more than 600m inside what is known as the Area of Separation (AoS).

Under the terms of Israel’s ceasefire agreement with Syria in 1974, the IDF is prohibited from crossing the so-called Alpha Line on the western edge of the AoS.

When contacted about the images, the IDF told the BBC its “forces are operating in southern Syria, within the buffer zone and at strategic points, to protect the residents of northern Israel.”

The imagery captured on 21 January shows new structures and trucks at the cleared area.

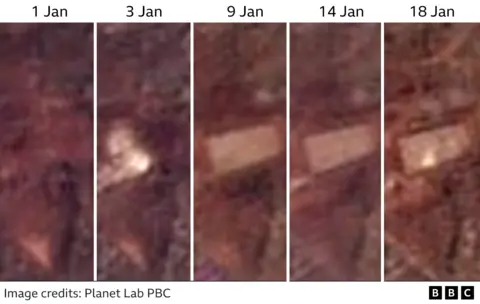

Construction appears to have begun at the beginning of this year, with lower resolution imagery showing gradual development at the site since 1 January.

A new track or road measuring around 1km also appears to join with a pre-existing road that leads into Israeli territory.

Drone photographs shared by a Syrian journalist 20 January shows trucks, excavators and bulldozers at the site.

Jeremy Binnie, Middle East specialist a defence intelligence company Janes told us: “The photo shows what appear to be four prefabricated guard posts that they will presumably crane into position in the corners, so this is somewhere they are planning to maintain at least an interim presence”.

NewsBeat

Storm Eowyn: All the cancellations and closures | UK News

Schools, rail services, sporting fixtures and hospitals are all set to be affected on Friday when Storm Eowyn slams into the UK.

A string of public authorities have issued statements warning the public to only travel unless absolutely necessary, while around 4.5 million people in parts of Northern Ireland and Scotland were sent an emergency alert on their mobile phones on Thursday evening.

It was the largest real-life use of the emergency system to date and caused mobile phones to make a loud siren-like sound, even if they were on silent when the alert was issued.

Speaking before it was sent out, a Cabinet Office spokesperson said: “The emergency alert system will send a message to every compatible mobile phone in the areas at most risk, containing information about the weather warnings and guidance on how to stay safe.”

Schools, colleges and universities

• All schools in Northern Ireland have been advised to close on Friday

• Schools and nurseries across central and southern Scotland have also been urged to shut

• Edinburgh Napier University, Queen’s University Belfast and Ulster University are among the sites closing their campuses to students and staff on Friday, with no access to any buildings

Health services

• NHS Lothian has cancelled all routine, non-urgent planned procedures on Friday and postponed the majority of hospital outpatient appointments to protect patients and staff

• NHS Lanarkshire has also postponed all non-urgent appointments in hospital and community settings

Rail services

• All ScotRail services will be suspended on Friday

• The West Coast Main Line north of Preston and the East Coast Main Line north of Newcastle will also be shut throughout the day, affecting Anglo-Scots services

• Network Rail says “other lines across northern England, Scotland and northern Wales may also be closed at short notice”

• Train services across Northern Ireland have also been suspended

• Transport for Wales has warned services may be subject to last-minute changes and cancellations on Friday

Roads

• Police Scotland has urged drivers not to travel

• RAC Breakdown has also advised motorists in areas covered by red weather warnings not to drive “unless absolutely essential”

• Bus services in Northern Ireland will be suspended on Friday

Airports

• Edinburgh Airport has said operations “will be limited” during Friday’s red weather warning, which is in place from 10am until 5pm. A spokesperson added: “Airlines will make decisions on the operations of their own flights”

• Glasgow Airport has warned passengers to “check the status of their flight with their airline before travelling” on Friday and Saturday

• Belfast International Airport issued similar advice and said it was “anticipating that the weather alert issued will result in flights being impacted”

Ferries

• All CalMac ferry services scheduled for Friday have been cancelled

• Northlink Ferries, serving the Northern Isles, has also amended its services for Friday and is keeping its sailings for Saturday under review, with “a high probability of cancellation” for morning services

Public services, spaces and other sites

• The V&A Dundee will be closed throughout Friday. It plans to reopen on Saturday

• All Scottish courts within or near to the red warning zone will be closed

• The Scottish Parliament will be closed all day on Friday

• Glasgow Life, which runs libraries, museums and cultural venues in the Scottish city, said all its sites would be closed on Friday

• Some children’s playgrounds in London parks, including Hyde Park, will be closed on Friday as a precaution

Sport fixtures

• The Scottish Women’s Premier League match between Celtic and Hearts, scheduled for 7.30pm on Friday, has been postponed

• Sheffield United’s home game against fellow Championship side Hull City at 8pm on Friday is still scheduled to go ahead

Politics

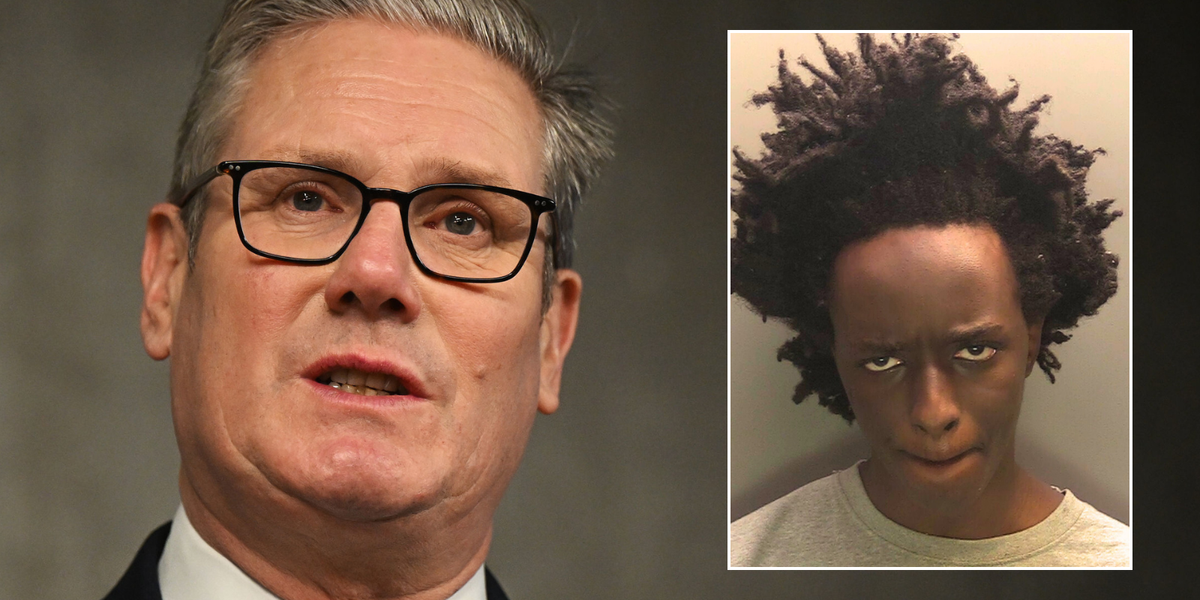

Keir Starmer ‘bending knee’ to Brussels as EU looks to undo Brexit with ‘disgraceful’ Customs Union deal

Sir Keir Starmer has been accused of “bending the knee” to Brussels as the European Union looks to strike a customs agreement with the UK.

The Prime Minister is under pressure to return Britain to the EU’s orbit after the EU’s new trade chief Maros Sefcovic stresseed such an agreement would represent membership of the Pan-Euro-Mediterranean Convention (PEM).

PEM operates under common rules which enable parts, ingredients and materials for manufacturing supply chains to be sourced from across dozens of countries in Europe and North Africa tariff-free.

The suggestion, rejected by the previous Tory Governments, was touted during Sefcovic’s appearance at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Keir Starmer

PA

The Prime Minister is unequioval about his determination to “reset” cross-Channel relations but continues to insist that this will not infringe on the UK’s decision to leave the Single Market or Customs Union.

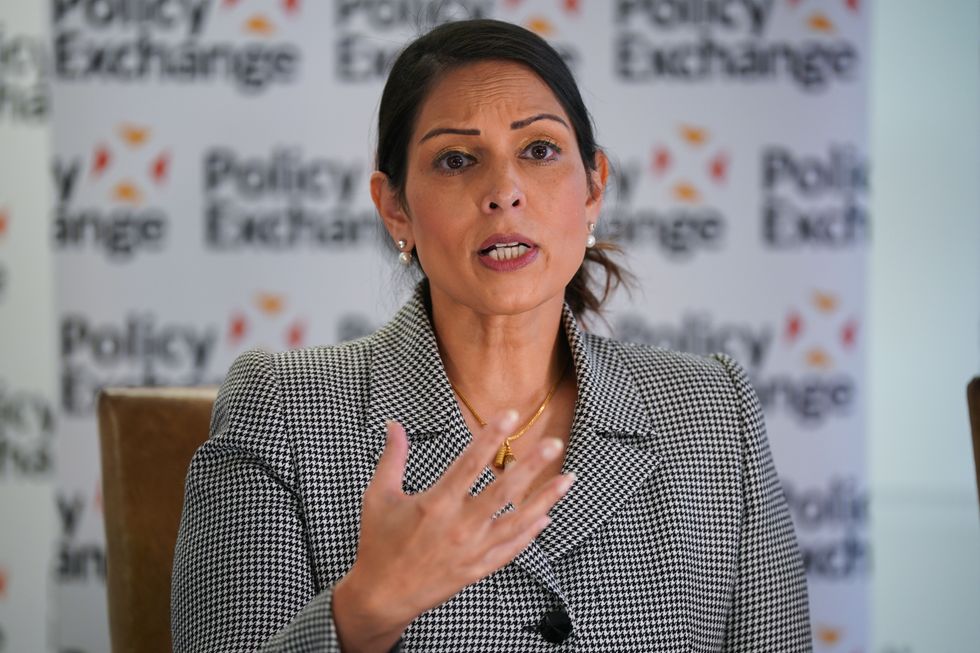

Responding to Sefcovic’s comments, Shadow Foreign Secretary Dame Priti Patel said: “Labour’s programme of bending the knee to the EU is disgraceful.

“These latest reports that the Government might shackle us to the European Union are deeply concerning, and once again make clear that Keir Starmer and his chums are all too happy to put their ideology ahead of our national interest, no matter the cost.

“The Conservatives will always fight for the democratic freedoms the British public voted for, and will not stand idly by in the face of Labour’s great betrayal of our country.”

Starmer’s Government is reportedly holding consultations with business leaders over the benefits of PEM but no final decision has yet been made.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

Priti Patel

PA

Brexiteers have long warned that being part of a Customs Union would block the UK from signing independent Free Trade Agreements, including with the United States.

However, Liberal Democrat leader Sir Ed Davey is already publicly calling for an official return to the Customs Union.

Davey, who is expected to call for the UK to rejoin the EU later down the line, argued it was needed to boost Britain’s economy and its ability to deal with the incoming Donald Trump presidency from a position of strength.

Sefcovic’s suggestion, rejected by the previous Tory Governments, was touted during his appearance at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

The Brussels bureaucrat said the idea has not been “precisely formulated” by London yet and the “ball is in the UK’s court”.

Sefcovic also hinted at a full-scale veterinary agreement to reduce frictions on farming and food trade, an updating fisheries deal and mobility plan for under 30s.

European Commission vice-president Maros Sefcovic PA

European Commission vice-president Maros Sefcovic PASefcovic said it was hoped the scheme would “build bridges for the future for the European Union and the UK”.

“That was the idea,” he said. “[But] we’ve been a little bit surprised what kind of spin it got in the UK.

“It is not freedom of movement,” Sefcovic added. “We have been very clear what we’ve been proposing.”

Despite rejecting previous calls for a return of Freedom of Movement, Starmer could face pressure next month while attending a defence and security focused EU summit.

The Prime Minister is determined to “reset” cross-Channel relations but continues to insist that this will not infringe on the UK’s decision to leave the Single Market or Customs Union.

Keir Starmer

Getty Images

And No10 has since left the door open to accepting Sefcovic’s PEM offer.

A Downing Street spokesman said: “The arrangement that’s been discussed is not a customs union.

“Our red line has always been that we will never join a single market, freedom of movement, but we’re just not going to get ahead of those discussions.”

However, MPs have already been exerting pressure on Starmer over under 30s being engaged in a free movement arrangement.

A 10-minute rule bill, introduced by Liberal Democrat MP James McCleary, will receive a second reading on July 25.

NewsBeat

‘We hope it haunts you every day’: Southport families speak out at Axel Rudakubana’s sentencing

Southport killer Axel Rudakubana has been jailed for 52 years after brutally murdering three young girls in a frenzied knife attack last year.

The “sadistic” 18-year-old, who had an obsession with violence, genocide and massacres, was given the life sentence at a packed out courtroom at Liverpool Crown Court on Thursday.

Throughout the sentencing, Rudakubana repeatedly interrupted the judge by claiming he needed a paramedic, as more than 30 members of his victims’ families sat in the public gallery.

Despite this, the court heard the heart-rending victim impact statements of parents of Alice da Silva Aguiar, nine, and Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven, who died in the onslaught.

The court also heard from a number of survivors, including the Taylor Swift-themed dance class instructor Leanne Lucas, 36, who said she has suffered scars she “cannot move on from”.

Here, The Independent has put together some of the heartbreaking victim impact statements read out at the court.

Family of Elsie Dot Stancombe

Elsie’s mother, Jenny Stancombe, described the attack as “the act of a coward” and said Rudakubana was “cruel and pure evil”.

Ms Stancombe said the attack had “stolen” her daughter from her but that it would “not take away our determination to honour her memory”.

Her statement continued: “We are not going to stand here and list everything you have taken away from us, because we refuse to give you the satisfaction of hearing it.

“We will not let you know anything about her because you don’t deserve to know the extraordinary person she was.

“You know what you have done and we hope the weight of that knowledge haunts you every day.”

Family of Alice da Silva Aguiar

In a separate statement read out in court afterwards, Alexandra and Sergio Aguiar said their daughter Alice’s death had “shattered our souls”.

They said: “In a matter of minutes our worlds were shattered and turned upside down by the devastating attack on our Alice.

“A pin drop that changed our lives forever. We kept our hopes up every second during Alice’s 14-hour fight. But, once she had lost her fight, we lost our lives.”

Mr and Mrs Aguiar added: “Living without Alice is not living at all. It’s a state of permanent numbness. We can’t see her picture and videos, they take us back to a time when we were so happy and now we’re in constant pain.

“We have her clothes, her teddies and other belongings. We’ll keep them safe and often hug them when we miss Alice.”

Dance class instructor Leanne Lucas

Ms Lucas told of living in constant fear since the attack, unable to feel safe at work or in public places and said she can not give herself compassion or accept praise, adding: “How can I live knowing I survived when children died?”

She said it left her unable to trust society, revealing the “badness” lurking in plain sight and altering her mindset to believe harm can happen to anyone.

The 36-year-old told the court that she dedicated her life to helping children and families, creating a safe community, but the attack robbed her of her role, purpose and sense of trust in herself.

Ms Lucas said: “On that day, I received several injuries that have not only affected me physically but also mentally. I, as do the girls, have scars we cannot unsee, scars we cannot move on from.”

NewsBeat

Bill Sweeney: RFU chief never considered resignation

Sweeney also denied speculation that he was planning to ride out the furore in the hope of stepping down in the wake of a successful Women’s Rugby World Cup later this year.

The tournament is being hosted in England, has already brought in record ticket sales, and the Red Roses are hot favourites to win the World Cup for the first time since 2014.

“I saw something a while back saying I have some specific bonus linked to a women’s World Cup win – that is not the case, that is not true,” Sweeney said.

“If I was in a mind to step down, I would have done it now and I wouldn’t wait until after a women’s World Cup.

“I still have some unfinished business here until the end of 2027. [England men’s head coach] Steve Borthwick is a great coach and we have a great squad of men’s players as well as women’s.

“There is a buzz and a good atmosphere around the place and I would like to see that through.”

Sweeney has said that, contrary to criticisms of his time in charge, he is proud of the RFU’s finances in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

The chief executive said record losses in the past financial year were down to the four-year cycle around the men’s Rugby World Cup, in which tournament years add extra expenses while wiping money-spinning autumn internationals off the fixture list, and a steep rise in utility and business costs.

He also defended his own pay, which was made up of £742,000 and a bonus of £358,000 last year.

Sweeney said that, while he had unsuccessfully explored the possibility of deferring his bonus payment, it was the result of a scheme intended to retain senior leaders through the pandemic and benchmark their performance against specific goals.

“When you are the recipient of something like an LTIP [long-term incentive plan], you don’t request it, you don’t design it, you don’t set the criteria for its payment,” he said.

“The payment was against very clear criteria of which 77% were hit, so part of me says that was put in place to deliver something to a level which we delivered.

“I don’t feel we need to apologise for that scheme.”

Sweeney and other RFU officials are embarking on a tour of grassroots clubs over the next few months to put forward their case before a special general meeting on his future.

Rob Sigley, the founder of the Community Clubs Union, believes it is already too late for Sweeney to win over many in the sport who feel that too much money has been focused on the elite game.

“We have openly called for his head and for him to resign,” said Sigley of Sweeney.

“He sits there at the top and is part of these decision-making processes and he’s accountable for it.”

NewsBeat

Queen evokes ‘deadly seeds of Holocaust’ in warning over antisemitism and Islamophobia | UK News

The Queen has urged people to heed the warning of history and speak out over rising levels of antisemitism and Islamophobia.

Speaking at an event to mark Holocaust Memorial Day, Camilla pointed out that the genocide of European Jews during the Second World War was foreshadowed by “small acts of exclusion, of aggression and of discrimination”.

She told the reception hosted by the Anne Frank Trust: “Today, more than ever, with levels of antisemitism at their highest level for a generation; and disturbing rises in Islamophobia and other forms of racism and prejudice, we must heed this warning.

“The deadly seeds of the Holocaust were sown at first in small acts of exclusion, of aggression and of discrimination towards those who had previously been neighbours and friends.

“Over a terrifying short period of time, those seeds took root through the complacency of which we can all be guilty: of turning away from injustice, of ignoring that which we know to be wrong, of thinking that someone else will do what’s needed – and of remaining silent.

“Let’s unite in our commitment to take action, to speak up and to ensure that the words ‘never forget’ are a guiding light that charts a path towards a better, brighter, and more tolerant future for us all.

“As Anne wrote in her diary on 7th May 1944: ‘What is done cannot be undone, but at least one can prevent it from happening again’.”

Read more

King to attend 80th anniversary of Auschwitz-Birkenau liberation

Pupils to ‘talk’ to Holocaust survivors with AI technology

Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany led the systematic murder of around six million Jews, around two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population.

Anne Frank kept a diary while in hiding in Amsterdam and it was published after the war, turning her into a globally recognised symbol of Holocaust victims.

She died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp aged 15, shortly before it was liberated by Allied forces.

Politics

Keir Starmer issues direct message to Southport community after Axel Rudakubana sentencing and vows action as he addresses ‘harrowing moment’

Sir Keir Starmer has branded Axel Rudakubana’s crimes “one of the most harrowing moments in our country’s history” in a direct message to the Southport community this evening.

Speaking after Rudakubana was sentenced to a minimum term of 51 years in prison, the Prime Minister said: “The thoughts of the entire nation are with the families and everyone affected by the unimaginable horrors that unfolded in Southport.

“No words will ever be able to capture the depth of their pain.

“I want to say directly to the survivors, families and community of Southport – you are not alone. We stand with you in your grief.

‘You are not alone. We stand with you in your grief,’ the Prime Minister said

PA

“What happened in Southport was an atrocity and as the judge has stated, this vile offender will likely never be released.

“After one of the most harrowing moments in our country’s history we owe it to these innocent young girls and all those affected to deliver the change that they deserve.”

Sarah Hammond, Chief Crown Prosecutor at the CPS’s Mersey-Cheshire branch, also paid tribute “to the victims and their families in this harrowing case” in a further statement on Thursday.

Calling Rudakubana’s crimes “dreadful”, Hammond said that the case “is one of the most harrowing that I, as the Chief Crown Prosecutor for this area, have ever come across”.

READ MORE AS AXEL RUDAKUBANA IS SENT DOWN:

Rudakubana was sentenced to a minimum term of 51 years in prison today

PA

“Axel Rudakubana is a murderer; utter devastation followed as he acted out a meticulously planned rampage of murder and violence,” she said.

“His purpose was to kill and he targeted the youngest, most vulnerable – no doubt in order to spread the greatest level of fear and outrage, which he did.

“Three days ago, he pleaded guilty to all 16 counts against him, saving the families of the victims the trauma of reliving the events of that day in a trial.

“But he has never expressed any remorse, only cowardice, in his refusal to face the families whose lives he has forever changed.

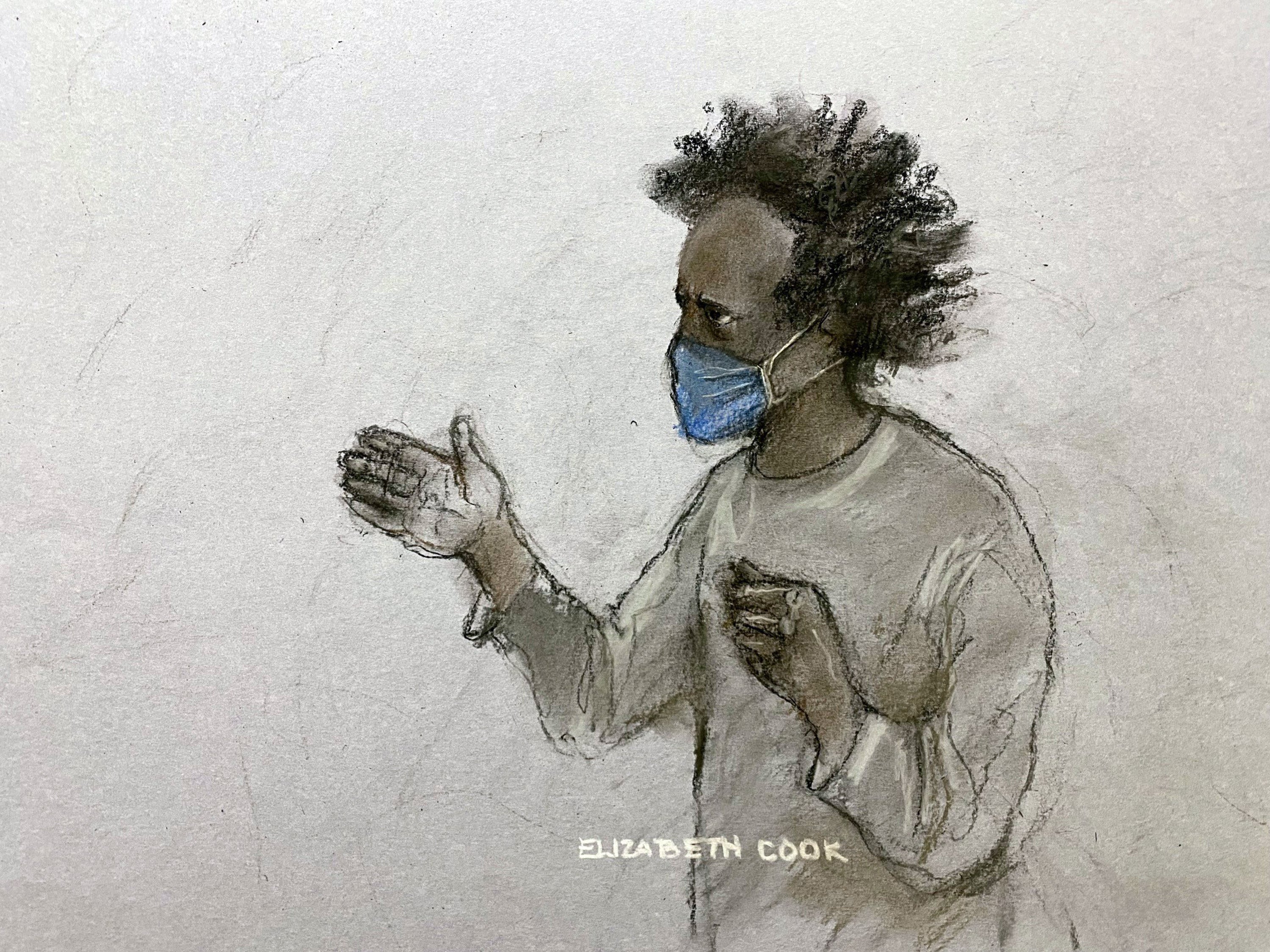

Axel Rudakubana, as seen in a court sketch from his sentencing hearing on January 23

PA

“This has been an extremely difficult case for the whole prosecution team and police officers at Merseyside Police. They have had to work through some harrowing footage and evidence.

“I would like to thank them for their perseverance, compassion and determination to achieve justice for the victims and their families.

“This sentencing brings to an end this case, but the events of that day will leave a tragic legacy that will unfortunately endure for many years.”

The victims and their families “have shown tremendous dignity and composure in the face of unbelievable horror”, she added.

NewsBeat

Axel Rudakubana likely to spend life in prison after being sentenced to 52 years for Southport murders

A disturbed teenager who murdered three innocent girls in a mass stabbing at a children’s dance class in Southport and later gloated “I’m glad they’re dead” is likely to never be released from prison.

Axel Rudakubana, 18, was sentenced to life with a minimum of 52 years for carrying out the horrific attack which was described as a “pre-meditated attempt to commit indiscriminate mass murder”.

The remorseless killer, who admitted 16 offences, was absent from the dock as the sentence was read out on Thursday, having twice been removed from court for shouting.

He was given 13 life sentences with a minimum term of 51 years and 190 days. Some time was taken off his 52-year sentence due to time already served in custody.

Judge Mr Justice Goose said he was unable to hand him a rare whole life order because he was only 17 at the time of the attack on 29 July last year. He turned 18 just nine days after the attack.

The teenager dramatically changed his plea on the first day of his trial on Monday, admitting to murdering six-year-old Bebe King, seven-year-old Elsie Dot Stancombe and Alice, who died from her injuries in hospital after she fled the rampage at a Taylor Swift-themed holiday class.

He also pleaded guilty to attempting to murder eight children who were wounded – with some stabbed in the back as they tried to escape – and two adults who tried to protect them.

He further admitted to producing the deadly poison ricin and possessing a document containing an al-Qaeda training material, which included information on knife attacks which he used to help plot his assault.

The judge said the killer was intent on “horrific extreme violence” and would have killed all 26 children at the class and any adult who got in his way if he could.

“In his mind was an intention to murder as many of them as he possibly could”, he said. “He wanted to carry out mass murder on innocent, happy young girls.

“Over 15 minutes, he savagely killed three of them and attempted to kill eight more as well as two adults who tried to stop him.”

The court heard how violence-obsessed Rudakubana had travelled by taxi from his home in Banks, Lancashire, to the Hart Space in Southport, where 26 girls aged six to 13 were attending a fully booked children’s holiday class.

They were making friendship bracelets and singing Taylor Swift songs when he entered the room wearing a surgical face mask and bright green hoodie, brandishing a 20cm kitchen knife.

He grabbed the nearest child and stabbed her, before he then moved through the room systematically stabbing as many as possible.

Some were stabbed in the back as they desperately tried to escape, with one girl later seen running out of the building only to be dragged back in by the knifeman.

Members of victims families sobbed in the public gallery as harrowing CCTV of the attack was played to the court. In the footage, girls could be seen screaming in terror as they fled the dance studio into the carpark.

Shortly afterwards, a seven-year-old girl dressed in summer shorts and stroppy top, was shown being pulled back inside the studio by Rudakubana. Later, she was seen stumbling out of the door with visible wounds – clinging to a wall for support before she collapsed on the floor.

When the girl’s father eventually arrived on the scene, her injuries were so horrific he did not recognise her because her long-blonde hair was so soaked with blood it looked brown, the court heard.

When police arrived, officers found Rudakubana at the top of the stairs standing over the lifeless body of Bebe holding the kitchen knife, which he dropped when officers told him to.

The “sadistic” injuries he inflicted on her and Elsie, who both died at the scene after suffering 122 and 85 sharp force injuries, were “untreatable” no matter how quickly paramedics arrived, prosecutor Deanna Hear KC told the court.

The teenager remained silent in police interview but appeared to gloat about the horrific attack in unsolicited comments made in the police custody suite, which were noted down or recorded on CCTV, saying: “I’m glad those kids are dead, it makes me happy.”

He also said: “I don’t care, I’m feeling neutral,” and “so happy, six years old. It’s a good thing they are dead, yeah.”

Police searches of his address and analysis of his computers uncovered a disturbing fascination with violence, death and genocide – as well as a plastic container of deadly poison ricin.

He had researched car bombs, detonators and nitric acid, and owned weapons including a machete, scabbard and another knife identical to the one used in the attack.

Searches of his devices also revealed an obsession with massacres, torture and a wide range of brutal conflicts, including the genocide in Rwanda, where his parents are from.

Detective chief inspector Jason Pye, the senior investigating officer, said the evidence showed this was “no random acts of violence, but a planned, premeditated attempt to commit indiscriminate mass murder”.

“He wasn’t fighting for a cause,” he said. “His only purpose was to kill and to target the youngest, most vulnerable, no doubt to spread the greatest fear and outrage.”

In a series of harrowing victim impact statements read to the court, class teacher Leanne Lucas, who was stabbed trying to protect the girls, said: “How can I live knowing I survived when children died?”

“He targeted us because we were women and girls, vulnerable and easy prey,” she added. “To discover that he had always set out to hurt the vulnerable is beyond comprehensible.”

Alice’s grief-stricken parents, Alexandra and Sergio, sobbed and wiped away tears as the court heard how their lives ended too after she succumbed to her injuries in hospital.

“Once she had lost her fight, we lost our lives,” they said in a statement. “Everything stopped still and we froze in time and space. Our life went with her. He took us too. Six months of continuous pain and a lifetime sentence of it.”

Merseyside chief constable Serena Kennedy said the “beautiful faces and names” of the three murder victims “will be etched on the minds of the people of Merseyside forever.”

“The victims were enjoying a day of youthful innocence, untainted by the twisted and unhealthy fascination with violence that drove Axel Rudakubana to carry out the atrocities he had planned in the days leading up to the event,” she added.

“His terrifying attack resulted in the deaths of Bebe, Elsie and Alice – according to prosecution counsel today two of those children suffered particularly horrific injuries which can only be described as sadistic in nature.”

NewsBeat

Charli XCX, Dua Lipa and Ezra Collective among most nominated

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCharli XCX leads this year’s Brit Awards with five nominations, including a nod for album of the year with Brat.

She is also nominated for artist of the year, best pop and dance act and song of the year with Guess, featuring Billie Eilish, which went to number one in August.

Her sixth studio album was released in June and grew into a cultural movement – Brat was crowned Collins Dictionary 2024 word of the year and it even reached US politics with presidential candidate Kamala Harris giving her social media a brat rebrand.

Seven-time Brit winner Dua Lipa has received four nominations including pop act which she won last year.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMaking an epic comeback this year is rock band The Cure who have received their first nomination in three decades.

Their album Songs of a Lost World, which is the band’s first new music in 16 years, is up for album of the year.

They are also nominated for group of the year and best alterative/rock act which is voted for by the public.

The Beatles are another oldie but goldie band nominated. They are nominated for song of the year with Now And Then, making it their first nomination since 1977.

Billed as their “final song”, Now and Then was started by John Lennon in 1978, but only completed in 2022 by Sir Paul McCartney and Sir Ringo Star.

Released in November 2023, the song meets the eligibility criteria as it has spent at least eight weeks in the top 15 ranked British songs based on sales.

Ezra Collective, make their Brits debut with four nominations. The group become the first jazz act to win the Mercury Prize in 2023 with their album Where I’m Meant To Be.

Similarly, The Last Dinner Party – last year’s rising star winners – have four nominations.

Both groups are nominated for album of the year, group of the year and best new artist.

Joining them in the best new artist category is Indie band English Teacher who won the 2024 Mercury Prize for their debut album, This Could Be Texas.

Myles Smith is also nominated in the category and his feel-good foot-stomper Stargazing, which became the biggest-selling British single of 2024, is up for song of the year.

At the award ceremony in March he’ll receive the Brit Awards’ rising star prize – following in the footsteps of Sam Fender, Adele and Rag ‘N’ Bone Man.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are 70 nominees across 13 categories.

Nominations in the three biggest categories are:

Artist of the year

- Beabadoobee

- Central Cee

- Charli XCX

- Dua Lipa

- Fred Again

- Jamie xx

- Michael Kiwanuka

- Nia Archives

- Rachel Chinouriri

- Sam Fender

Group of the year

- Bring Me The Horizon

- Coldplay

- The Cure

- Ezra Collective

- The Last Dinner Party

Album of the Year

- Charli XCX – BRAT

- The Cure – Songs of A Lost World

- Dua Lipa – Radical Optimism

- Ezra Collective – Dance, No One’s Watching

- The Last Dinner Party – Prelude to Ecstasy

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBritish artists up for multiple awards this year include Beabadoobee, Central Cee, Chase & Status, Fred Again, JADE, Nia Archives, Michael Kiwanuka, Rachel Chinouriri and Sam Fender.

Coldplay, who headlined Glastonbury last year, have received nominations for group of the year and song of the year with feelslikeimfallinginlove. However, the British band’s 10th album – Moon Music – was not nominated for album of the year.

The international artist of the year category is once again a tough battle with the majority of nominees being female American pop singers. Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Sabrina Carpenter, Chappell Roan and Billie Eilish are among the nominees.

Roan has just won BBC Radio 1’s Sound of 2025 – the station’s annual poll to identify music’s biggest rising stars.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNewsBeat

Teenager guilty of murdering Kamari Johnson in row over stolen moped | UK News

A 17-year-old has been found guilty of murdering a boy who he stabbed in broad daylight following a row over a stolen moped.

The killer, who cannot be named because of his age, attacked 16-year-old Kamari Johnson with a machete in Hayes, west London, on 24 May last year.

The Old Bailey heard the pair met up after the defendant made contact over Snapchat about wanting to buy the moped from Kamari.

The two “haggled” over the price, with Kamari wanting £180, prosecutor Joel Smith KC said.

However, when they met up, Kamari took the defendant’s money and drove off, jurors were told.

Mr Smith said: “It seems that when they met, having taken [the defendant’s] cash, Mr Johnson went back on his side of the deal and simply rode off. In short, he took the money and ran.”

The prosecutor said the defendant was left feeling “pretty foolish, pretty embarrassed and, no doubt, pretty angry”.

He told jurors: “But whatever Mr Johnson had done, you may feel, he didn’t deserve what happened next.”

Minutes later the 17-year-old walked to Kamari’s house to confront him and get the bike, the court heard.

Mr Smith said: “He knew where Mr Johnson lived and he went there looking for him, and when he found him, he stabbed him.

“He stabbed him once through his chest and into his heart, and although Mr Johnson managed to flee on the moped, he collapsed minutes later and died on the street.”

Read more from Sky News:

Southport child killer jailed for minimum of 52 years

Red weather warning over Storm Eowyn

Sainsbury’s to cut 3,000 jobs

CCTV footage played to jurors showed the defendant turning into the victim’s road. About 20 seconds later, Kamari was seen driving out of the road on the black moped as the defendant chased after him, carrying a large knife with a curved blade.

A witness described seeing the 17-year-old carrying a blood-stained knife he estimated to be about 30cm long, the prosecutor said.

Further CCTV video played in court showed Kamari crashing the moped in a nearby pub car park and then collapsing.

In police interviews, the killer declined to answer questions but claimed in a statement that he “acted in self-defence at all times”.

The youth made no reaction and Kamari’s family members wept in court as the jury announced its verdict after deliberating for 13 hours and 35 minutes. The youth was also found guilty of having an article with a blade or point.

Detective Chief Inspector Alex Gammampila, from the Metropolitan Police, said: “This was a senseless killing, which took place out in the open. Members of the public rushed to Kamari’s aid but were unable to save him.

“In the absence of a murder weapon, CCTV evidence proved crucial in convicting the killer. Residents around the scene of the crime were encouraged to upload footage from their own cameras to an online portal. From this, investigators were able to reconstruct the killer’s movements on the day.”

He added: “My thoughts are with Kamari’s loved ones, who have suffered an unimaginable loss. I also pay tribute to the members of the public who came to Kamari’s aid as he lay dying, and to those who assisted with the investigation.”

The defendant is due to be sentenced on Friday 14 March.

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years agoThese ’90s fashion trends are making a comeback in 2025

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe Season 9 ‘ Game of Thrones’ is here.

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago9 spring/summer 2025 fashion trends to know for next season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe old and New Edition cast comes together to perform You’re Not My Kind of Girl.

-

Sports8 years ago

Sports8 years agoEthical Hacker: “I’ll Show You Why Google Has Just Shut Down Their Quantum Chip”

-

Business8 years ago

Uber and Lyft are finally available in all of New York State

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Disney’s live-action Aladdin finally finds its stars

-

Sports8 years ago

Steph Curry finally got the contract he deserves from the Warriors

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Mod turns ‘Counter-Strike’ into a ‘Tekken’ clone with fighting chickens

-

Fashion8 years ago

Your comprehensive guide to this fall’s biggest trends

You must be logged in to post a comment Login