Women are paying for doula services in increasing numbers. And not just for birth.

There are now doulas – non-medical professionals who offer guidance and support – for all manner of milestones, from menopause to divorce.

In the birth context, it comes amid anxiety around NHS maternity services, which this year a parliamentary inquiry found to be “shockingly poor quality”, with good care “the exception not the rule”.

With their rise in popularity, both doulas and their clients have accumulated certain stereotypes.

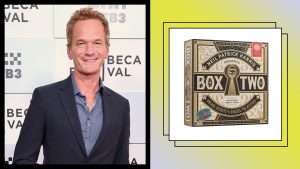

Gill Bell, 36, opted for a doula for the birth of her second child.

“I wanted someone practical, who would give me evidence-based information – and that’s what I got,” she tells Sky News.

“There’s maybe a stereotype that doulas are a bit hippy-dippy. But I wanted somebody I could trust, I felt had a solid background.”

Her decision came after the “traumatic” caesarean birth of her first daughter amid COVID hospital restrictions, which she says left her with recurring nightmares.

“They went on for two or three years. It really put me off extending our family because I was so afraid to go through that again,” the mother-of-two from Derry, Northern Ireland, says.

But after a recommendation from a friend, she chose to pay £800 for a doula for her second birth. From accompanying her to appointments, to being there for the birth itself – Gill believes having her doula “hold her hand and tell her everything was going to be okay… healed” the trauma from her previous experience.

“I wanted help to overcome it because I knew it was going to affect my next birth,” she says. “Right throughout my pregnancy she knew inside out what had happened before and how I felt about everything.”

With her doula advocating for her, Gill was able to have a water birth at home – which she believes was a first for any woman after a C-section at her local NHS trust.

Describing it as her ideal scenario, she says: “My daughter came into the world in the most beautiful way.”

What is a doula?

The word doula comes from the ancient Greek for “female slave”.

According to Doula UK, the voluntary organisation that accredits around 700 birth doulas nationwide, they provide “continuous physical and emotional support, information, and advocacy during pregnancy and birth”.

The Royal College of Midwives stresses they “must not provide clinical care at any time” but uptake “may reflect some of the pressures faced by maternity services”.

Sky News spoke to doulas who specialised in various areas – from birth and death, to abortion and cancer.

They vary in price – from less than £50 for a one-off hour on Zoom to between £1,000 and £6,000 for months of support, including being available 24/7 on WhatsApp. Others offer their services for free or are paid for by NHS pilot schemes.

Although a key part of what they do is emotional support, all the doulas we spoke to stressed they weren’t therapists either.

“My clients ask me to share my story – a good coach or therapist won’t do that,” one says.

Professor Sara Benetti, Gill’s birth doula, believes “doula-ing” is the same regardless of the context.

She is a marine scientist from Italy who has lived abroad – in the UK and US – for more than 20 years. She trained as a doula to help other women giving birth in a foreign country.

“We’re called doulas – but really we’re just providing emotional support at key stages in life,” she says.

Here we delve deeper into what doulas offer at each milestone – and why women are calling on them for more and more throughout their lives.

Divorce

Farhana Hussain is a divorce doula. She was a mother-of-three, working part-time, who had been married for 15 years when she got divorced in 2019.

The 47-year-old from Kent says she hid the separation from the rest of her family for almost two years.

“I’m from a South Asian, Muslim family and my partner was of a white, Christian background – so it was a huge thing us getting married,” she tells Sky News.

“We had really broken the taboo of mixed-heritage marriages – so the idea of them saying ‘I told you so’ was too much for me to handle.”

She adds that she was “too scared to go lawyers”, feeling “stupid” because she was “completely dependent” on her husband, as he handled their finances.

Suffering from chronic insomnia, she says her GP prescribed her antidepressants she didn’t want to take, and she went through a “series of counsellors” – but was left feeling “more and more awful”.

“They were white, often male, therapists who hadn’t been through divorce,” she recalls. “They were good at their jobs but it just felt so unhelpful – I needed somebody who got me.”

While attempting to “figure it out on her own”, she realised people started coming to her for advice on their own divorces.

She completed qualifications in coaching and neurolinguistic programming but recalling the experience of having a doula for her second birth – she decided a “divorce doula” was what she wanted to become.

She said: “I’m rebirthing people into that next chapter of their lives – that’s why I liked the term doula.”

Dr Sarah Dustagheer, a reader in modern literature at the University of Kent, is one of Farhana’s clients.

The mother-of-two decided on a divorce doula after her 11-year marriage to the father of her two daughters came to an end.

She admits being “somewhere on the cynical side… especially as an academic” but when she stumbled across Farhana’s services she realised: “I hadn’t done the work I needed to do.

“On paper my divorce was done, it had been a year… but I was still in defence mode.”

Although childcare was finalised and she had bought her ex-husband out of the family home, she describes her “confidence being on the floor”, having to navigate her new life as a single parent.

This included losing her ex’s family, certain friends who “didn’t understand”, and returning to work after a period of stress leave.

Read more from Sky News

‘Life-ruining’ migrant visa delays

‘My bum is for sale – my artistic vision isn’t’

How much it costs to freeze your eggs

She says having a doula offered her peer support, spiritualism, meditation, and visualisation techniques she hadn’t got from therapy.

“Doula-ing is much more future-focused,” she says. “It feels more positive – about what you want from life now.”

On stereotypes and privilege (sessions are £375 fortnightly for four months), she says: “I made a decision to invest in myself. It’s a shame more people can’t access that. But as a society, employers need to think more about how they support people.

“In the employee life cycle, divorce is a top three event. So if people have to get private support – that’s an employer failing their employees.”

She adds that with social prescribing, she hopes in the future something like a divorce doula might be available on the NHS.

Menopause

Emma York, 45, booked a session with a menopause doula after missed periods resulted in repeated pregnancy scares and brain fog left her struggling at work.

Despite suffering a year of unknown symptoms, she felt there would be “nothing a GP could prescribe”, and at 44, she had been told she was “too young” to be menopausal.

“You don’t get a booklet. You have no idea,” she says. “In the last two years my periods have gone on holiday – and I had no clue it could be menopause – I thought I could be pregnant three times.”

The digital marketing specialist had run her own business for more than 10 years – but says she increasingly found herself forgetting things and feeling nervous talking to clients.

“I know I’m very good at what I do. And I’m self-employed, so my business is my life, but all of a sudden it was an issue and I didn’t feel comfortable,” she says.

Unconvinced her GP could help and having never had therapy, Emma came across a woman describing herself as the UK’s first “menopause doula” through a work event.

Fiona Catchpowle, 57, set up The Menopause School at home in Birmingham in 2020.

She too was driven by her own negative experiences. She found mystery symptoms in her early 40s “scary and exhausting” and only found out they were perimenopause at 48.

“I kept forgetting what I’d said after 30 seconds. There was brain fog you worry is dementia and then crushing moments of fatigue,” she tells Sky News.

“Half of it is the symptoms themselves and the other half is the despair and anxiety of not knowing.”

Fiona had previously worked as a biology teacher and was shocked to realise she hadn’t ever taught her students about menopause – or menstrual health.

When she “couldn’t find a single wellness professional” to help her with her own symptoms, she says: “I decided to become one. It wasn’t a career move – it wasn’t like I went into it to make money – that was the whole purpose – to fill the education gap.”

As a menopause doula, she charges £45 an hour for one-off sessions – either in-person or online – and gives talks to businesses and schools.

She also runs a course to train other menopause doulas, which costs £600, with students in the UK, US, Europe, and Saudi Arabia.

Emma says that an hour with Fiona made her feel “seen, heard, and less alone”.

“The fact she was a woman, from the same demographic as me, with so much expertise. I just felt very comfortable having the conversation.”

Fiona says her other clients include women who have been prescribed hormone replacement therapy (HRT) but are “too afraid to use it” and some in their 60s still experiencing menopause symptoms wondering “how long will this last?”

“To me a doula is someone who passes on knowledge – and who guides, nurtures, and supports,” she says.

Abortion

Naomi Connor works as an abortion doula in Belfast.

She is part of Lucht Cabrach – a network of volunteers who ensure women have access to terminations in Northern Ireland after they were decriminalised in 2019.

Unlike other doulas, Naomi and her colleagues do not charge for their services. They can accompany women to appointments and are on hand throughout the process to answer questions and provide support.

“Abortion is cloaked in so much silence and stigma. But women want to know how much should they cramp, how long it should last, how much bleeding is too much. So I can be at the end of the phone talking through what’s happening.”

Lucht Cabrach’s umbrella organisation, Alliance for Choice, also funds care packages. Naomi is a co-convener for them and also lectures part-time.

Since decriminalisation, some politicians with pro-life views have refused to commission abortion services in Northern Ireland, leaving providers with no funding or guidance. It is also the only part of the UK where abortion pills are not available for women to take at home (telemedicine), which together, Naomi describes as a “constant battle”.

“For some people it’s just about telling someone ‘I’m having an abortion. I’ve made my decision and I want to talk about it,” she explains.

The 52-year-old got involved in campaigning and trained to be doula after she travelled to England for an abortion in her early 40s, 12 years ago.

She had two adult children and was married to her second husband, with whom she had agreed not to have any more children.

“I became pregnant and I didn’t want to be and I was astonished at the complications of arranging an abortion in Northern Ireland,” she recalls.

Travel and the cost of the procedure totalled more than £1,000. She says she made the round trip in a day despite having a general anaesthetic.

“I went there and back on a Saturday and went straight back to work on the Monday – still bleeding,” she says. “I remember getting off the plane and thinking this can’t prevail.”

Cancer

Talaya Dendy, from Minnesota, believes she was the only person in the US offering cancer doula services when she started her business On The Other Side in 2019.

“I created this role. I filled a need that I had for myself,” she tells Sky News.

Ms Dendy, now 50, was 36 and working as a supply chain analyst when she was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 2011.

Although she says her oncologist and healthcare team were good – the system offered no emotional support.

After six months of chemotherapy and one of radiotherapy, she says she “didn’t feel herself” for almost two years after diagnosis.

“Healing isn’t just about the physical – it’s the emotional, mental, spiritual – all those things are impacted when a person gets cancer,” she says.

Having trained as a patient advocate, mental health first aider, and certified coach – she began calling herself that, but found the term didn’t resonate.

“Coaches are everywhere – what I do is special,” she says. “I got all the qualifications I thought I would need to support people, but nothing trumps lived experience.

“I started researching the word doula and if you don’t attach it to birth or death – it’s someone who supports another person through a major life event or significant health-related experience – and cancer is definitely those things,” she adds.

Thirteen years after her diagnosis she has around eight clients at a time – offering them two hour-long online sessions a month for a minimum of three – which totals $1,440 (£1,100). She also does health consultancy work to top up her income.

She says most clients approach her when they are either newly diagnosed or having problems with their treatment. A small number reach out when they’re in remission and are struggling to adapt. They have rarely been given a terminal diagnosis.

All her clients so far have been women, she says, who have tended to have different concerns depending on their race.

“With black women it’s: ‘They talk about me as if I’m stupid’, ‘They don’t even listen to me or ask about my cultural preferences’.

“For white women it’s been more – ‘how do I juggle all this with my career?’, ‘my marriage is suffering’, or ‘my spouse has left me because of my diagnosis’.”

Death

Dr Emma Clare is the director of End of Life Doula UK.

She has been a practising “death doula” since 2018, having trained as a psychologist and completed a PhD on death competency in healthcare professionals and the “de-medicalisation” of dying.

According to Marie Curie’s Better End of Life report 2024, most deaths in England and Wales (around 38%) happen in hospital, with more than half of people using an ambulance at least once in the final three months of their life.

The survey also found that people who spent their last week of life in hospital suffered the most physical and psychological symptoms – and those at home the least.

“Often when someone is dying their family rings 999 even if they don’t need to go to hospital,” Dr Clare says. “Information isn’t often shared between services so then people’s wishes are easily lost.”

She adds that a culture of “avoidance then ignorance” means a lot of families have little idea how their relative would like to die – and with stretched resources, the gaps being filled by end-of-life doulas are “wider than ever”.

The 34-year-old says hospital and care staff are almost always happy for her to be there, knowing “we have the luxury of time to spend with people” they don’t.

End of Life Doula UK has carried out two NHS pilot projects, with preliminary findings showing a reduction in unnecessary hospital admissions in the final weeks of life.

Dr Clare’s first experience of death in her own life was in her final year of university, when her grandmother died of a sudden brain haemorrhage.

“I think that’s how a lot of us come to this work – through our own experiences,” she says. “I just remember being extremely calm and able to think through what needed to happen in that moment.”

Accredited end-of-life doulas have spent around 10 days and £800 completing their training – and can progress to a diploma that involves a larger portfolio of casework.

Dr Clare says although most of her clients have a terminal diagnosis, she has also had younger people approach her who are “fit and healthy but just want to plan ahead”.

Antidote to misinformation

So why are doulas on the rise?

Beyond birth, there could be many reasons people feel they need extra support with key life events, consultant psychologist Dr Sandra Wheatley tells Sky News.

Firstly, the overwhelming volumr of information – and misinformation – online creates the need for “clarity” and “validation” from someone outside friends and family, who could bring their own biases.

More people also live apart from their relatives and some choose not to seek help from the community around them for “fear of judgment”, Dr Wheatley says.

“It’s not that communities don’t accept new people – it’s that we don’t reach out to them. With society evolving in such a way it’s no surprise to me that things like doulas have become more popular.”

On the stereotypes, she says: “It’s curious that when doulas are seen as something for privileged, white, middle-class people it’s said with such envy – as if it’s something everybody should have. People do it down, but they imply they would like to have access to it too.”

In terms of the benefits, paying for someone to support you unconditionally through a major transition doesn’t just help that person, she adds, but saves the “massive” cost of lost working hours and additional healthcare should they struggle to cope.

“It’s not complicated. If someone has an experience and is then prepared to put that much effort into accompanying other people through theirs – that’s a great thing,” she says.

More risk for the doula than client

And as for the risks, Dr Wheatley believes the burden falls heavier on the doula than the client.

Similarly to psychotherapists, which also have no statutory regulator, doulas are vulnerable to malicious complaints and poor insurance cover.

“You should be cautious people are doing it for the right reasons – make sure your family or partner meets them too. But a good doula will have the same concerns as you – ‘why are they coming to me?’, ‘am I putting myself in a dangerous situation?'”

Ultimately what links every type of doula is the passing on of their own lived experience.

When asked if a man could be a birth doula, for example, Gill says: “I struggle to see how. It’s so important a doula has experienced birth.

“Perhaps a male doula would have a place for someone giving birth who doesn’t identify as female – but they need to understand what the person is going through – so I personally wouldn’t have felt comfortable with one.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours