NewsBeat

‘I hid Sara Sharif’s family during international police hunt’

A man armed with an AK-47 assault rifle waves us down an alley. We’re in a small village in eastern Pakistan, to meet someone who says he can tell us how Sara Sharif’s family managed to hide from police for more than four weeks during an international police hunt.

He was the one who hid them, he tells us.

For nearly a month, police searched for the family of eight – Sara’s father Urfan Sharif, her stepmother Beinash Batool and uncle Faisal Malik, along with five of her siblings.

They had flown to Pakistan on 9 August 2023 – a day before 10-year-old Sara’s battered and lifeless body was found in a bedroom at their home in Woking, Surrey.

Having received a notice from Interpol to locate Sharif, Batool and Malik, police started a high profile search for the family across Pakistan, deploying multiple teams.

They suspected Rasikh Munir, a relative of Urfan Sharif’s, of helping them. But during multiple raids on his property, they failed to find the family.

The children were later found at another relative’s home. Mr Munir told us that was the moment Sharif, Batool and Malik decided to fly back to England, where they were finally arrested on 13 September 2023.

The BBC has followed the story in Pakistan since the first media reports of Sara’s death broke.

We met Rasikh Munir before Sara’s father, uncle and stepmother were put on trial for her murder in London, before the jury heard horrific details of the injuries that Sara had sustained – bite marks, iron burns and injuries caused by hot liquid.

He told us he had believed Sharif was innocent and that he’d taken the family in to protect the children. He also revealed extraordinary details: about how the family had hidden in corn fields when police raided his home at night and how he’d driven them around the local area, buying ice creams and even visiting hairdressers while detectives searched for them.

And remarkably, he said Sharif, Batool and Malik had been hiding in a neighbouring house just metres away from us as we spoke to Sara’s grandfather shortly after her siblings had been taken away by police.

A jury at London’s Old Bailey has now found Sharif and Batool guilty of murdering Sara. Malik was cleared of murder but has been found guilty of causing or allowing her death.

Olga Domin

Olga DominWe meet Rasikh Munir on the outskirts of Sialkot, an industrial district in Punjab, surrounded by rice fields and corn crops.

There is barbed wire above the gate to his house and a security camera is trained on us. He welcomes us in, wearing a tracksuit and sliders.

Before we met, Mr Munir told me he’d done nothing wrong in hiding the family. There was no Interpol request for their arrest when he hid them, but he knew police wanted to speak to the family about Sara’s death.

When we come face-to-face, I wonder if he’ll be coy about his involvement, yet within minutes of entering the house, his tour begins.

“This was Urfan’s room,” he says, showing me a dark bedroom with the curtains closed and a white bed frame with a yellow patterned sheet. “They [Sharif and Malik] used to sleep here, they used this table for food.”

He points to a red plastic table and blue sofa. “They used to sit here with Beinash to contact the lawyer and discuss how they should talk to police in the UK.”

He takes me through to a second bedroom, hung with dark red curtains and a double bed squeezed beside a wooden wardrobe. This, he says, is where Batool and the children used to sleep – some on the bed, some on mattresses on the floor.

As we talk, I notice the outline of a gun tucked in his waistband. When we ask about the weapons, we are told they are for protection from thieves.

We climb out onto an open, flat roof, strung with an empty washing line. “From this roof, you could see the police from all four sides,” Mr Munir says pointing across the open fields.

Bar a few one-storey buildings and a scattering of trees, the view is nearly clear to the main road.

Police came to the property on several occasions at night. Mr Munir tells us the family hid from officers in a thick field of corn, a few metres away from the house – the adults and all five children hiding in the dark, in hot, humid conditions.

“No police ever checked this area. The kids had just one bag, they didn’t have many clothes with them. Most of their stuff was in my car, which I used to park in a safe place,” he says.

“The younger ones didn’t know what was happening,” he says. “They were scared, they couldn’t understand.”

This was not the first time the family had visited the house. Last time, Sara had been there too. “She was a very nice girl,” Mr Munir remembers.

During the international police hunt, he says the family stayed with him for several weeks, but they weren’t in permanent hiding.

He tells us he drove them back and forth between his house in Sialkot and the city of Jhelum, two hours away, where Sara’s grandfather lived. He took them to have haircuts in town and sometimes for ice cream and pizza.

Before the police hunt intensified, he says the family was able to pass through police checkpoints without incident.

But then the net began to tighten.

Just over three weeks into the search, police found Sara’s siblings at their grandfather’s home. The BBC spoke to him minutes after the raid.

“The police have taken away all the children,” Muhammad Sharif told us. “They were safe with me.” He said Sharif and Batool weren’t there during the raid, but the police took all five of the children.

We were the first journalists inside the house after the raid. The neon plastic toys the children had been playing with were still on the beds. The smashed door was freshly splintered.

Now, Mr Munir tells us something incredible.

As we’d been filming that day, Sara’s father, stepmother and uncle had been hiding in the house next door – just metres away.

He says police only had permission to go into the grandfather’s house, so couldn’t check other nearby properties.

Cameras had been installed, attached to a big LCD screen, so the family could see when the police were coming.

The night the police closed in, Mr Munir says Sara’s father, uncle and stepmother “ran away”. They called him and he went to pick them up.

He says the family realised the game was up the following day. A court instructed that the children be placed in a children’s home in Pakistan.

We attended the hearing. The eldest of the five children carried the youngest through a crowd of police officers and local journalists, trying to protect their faces from camera flashes.

Mr Munir says the loss of the children and the growing police pressure prompted the adults to return to the UK. He said Sharif, Batool and Malik then contacted a UK lawyer and Surrey Police to say they’d be back within days.

He told us he booked flights in their names, even though there was an Interpol notice to find them. Mr Munir said he drove the trio to the airport and that Urfan even called him from the departure lounge to say they had cleared airport security.

When they arrived at Gatwick Airport, all three were arrested for Sara’s murder. The following month, a court allowed all the siblings to stay temporarily with a relative in Pakistan. Surrey County Council is still trying to bring them back to the UK. Their family in Pakistan is fighting to keep them there.

It is difficult to confirm every aspect of Mr Munir’s story. He has no photos of the time the family was with him – his phone was taken by the police, he tells us.

He has remained consistent and detailed in his story. He didn’t come to us. After several months of searching, we found him. We also know the police raided his property and were suspicious of his involvement from early on.

Throughout our conversation I was curious why he was happy to speak to us.

“One should tell what has happened,” he says. “The person who hides reality is not a good person.”

But when Mr Munir took the family in, he knew the 10-year-old girl he had met several summers before had been found dead and that police wanted to speak to the three adults hiding in his house.

The murder trial in London has since heard how Sara’s body was found with dozens of injuries. She had been hooded, burned and beaten during more than two years of horrific abuse.

Mr Munir was clear, even before the trial, there should be consequences for her brutal death. “Whoever has done this to Sara should be punished because they have done a great injustice,” he says.

It seems a contradictory response from someone who knowingly hid the three adults.

I kept pressing Mr Munir on whether he felt he had done anything wrong in hiding the adults and why he had helped the family.

“The case was in the UK, it had nothing to do with Pakistan,” he says. “Had it been a matter in Pakistan then maybe I wouldn’t have taken such a big risk.

“I helped Urfan and the young children. If I hadn’t helped them, they would have been completely helpless. I helped them to look after the kids, I felt sympathy for them.

“They were my people. Had I not stood by them and something bad had happened to them who would have been responsible for them?”

Sara’s grandfather and other members of the family have repeatedly lodged complaints in court that their family members were picked up by police to apply pressure on them to give up their whereabouts.

Police in Pakistan deny this. They say, since the hunt, all the cases against the family have been dropped.

But the consequences of the decision to bring the five children to Pakistan are not over.

All five, who until that point had spent their lives in the UK, are still in Pakistan. For now, their future is still uncertain.

NewsBeat

Axel Rudakubana: Inside the courtroom where grieving families refused to be overcome by killer’s antics

Inside Liverpool Crown Court, a tense silence descended as victim’s families gathered in the public gallery, anxiously waiting for Southport killer Axel Rudakubana to enter the dock.

The sentencing hearing, scheduled for 11am, had already started late as police, legal teams, families and journalists had made their way through enhanced security amid heightened tensions over the shocking case.

Every seat was taken, with some choosing to sit in parts of the public gallery with no view of the dock. A piece of frosted glass obscured any chance of catching even a fleeting glimpse of the remorseless killer, described by his own lawyer as having a “total lack of empathy”.

Others, including the grief-stricken parents of Alice da Silva Aguiar, Alexandra and Sergio, had a clear view of the daughter’s murderer.

They watched as Rudakubana, tall and slight, finally entered the glass-screened dock wearing a grey prison-issue tracksuit and a surgical facemask like the one he wore on the day he targeted 26 defenceless girls at a Taylor Swift themed holiday class in Southport last July.

He refused to speak when asked to confirm his identity and sat slumped in the dock with his head bowed accompanied by five dock officers.

The sentencing hearing had come more rapidly than anyone had anticipated. They had all been braced for a harrowing four-week trial which they were spared after the 18-year-old changed his plea without warning on Monday. However, any hope the families had that Rudakubana would accept his punishment with dignity were soon dashed.

Within minutes of prosecutor Deanna Heer KC launching her address, Rudakubana – who had refused to speak entirely at several previous hearings – started to shout over her.

“I need to speak to a paramedic,” he shouted. “I need to speak to paramedic I feel ill.”

Reports published that morning, later contested by police, claimed he had been taken to hospital from prison before the hearing.

Rudakubana’s lawyer Stan Reiz KC revealed prison staff had raised concerns over his wellbeing and his ability “to be in a high-pressure situation”.

“He has not eaten for a number of days and he’s drunk very little over a period of time,” the lawyer said.

However judge Mr Justice Goose said he had been examined by healthcare professionals before the hearing, who determined he was fit to attend, and told him to stay quiet.

“I can’t remain quiet because I am ill judge,” he protested. “I haven’t eaten for ten days and I’m not going to remain quiet.”

Despite attempts to carry on, he continued to shout over Ms Heer and then told his lawyer he was experiencing chest pains.

The judge, determined to continue, warned him “shouting from the dock is not going to make this happen any quicker”, but the killer refused to stop interrupting. He was ordered from the dock.

A family member shouted “coward” as he was led to the cells by dock officers, while others shook their heads in disgust.

The evidence that followed as Ms Heer recounted the horrifying details of the brutal knife attack was harrowing. Families broke down in the public gallery, with many leaving the court before distressing CCTV footage of the screaming girls fleeing in terror from the knifeman was played.

One clip showed Rudakubana grabbing a girl as she tried to escape and pulling her back into the Hart Space. Moments later, the seven-year-old dressed in summer shorts emerged stumbling and disoriented with visible injuries.

She clung to a wall for a few seconds, looking for her route to safety, but collapsed on the floor. Miraculously, she survived her injuries.

After lunch Rudakubana returned to court, having been seen again by healthcare professionals. He had told his lawyer he would be quiet, but within minutes the interruptions resumed.

“Judge, judge I feel really ill,” he continued. “I need to be seen by a paramedic.”

The judge responded: “He has been seen by a paramedic – two teams of paramedics who deem he’s fit”, before he was ordered from the dock for a second time.

His absence meant he was not in court to listen to a string of devastating victim personal statements, some of which were delivered in person.

One brave survivor, aged just 14, who was stabbed in the back and arm delivered her own victim statement via videolink. She demanded “give me a reason for what you did” as she told her attacker: “I hope you spend your whole life knowing that we think you’re a coward.”

Jailing him life with a minimum of 52 years, Mr Justice Goose said it was highly unlikely Rudakubana would ever be released.

Some family members could be heard to take an audible breath as the sentence was announced. Outside court, they held hands and hugged.

Later, police lined the street as Rudakubana’s prison van was set to leave the court. The killer, who will likely serve his sentence in a maximum security jail, will not be eligible to apply for parole until 2077.

NewsBeat

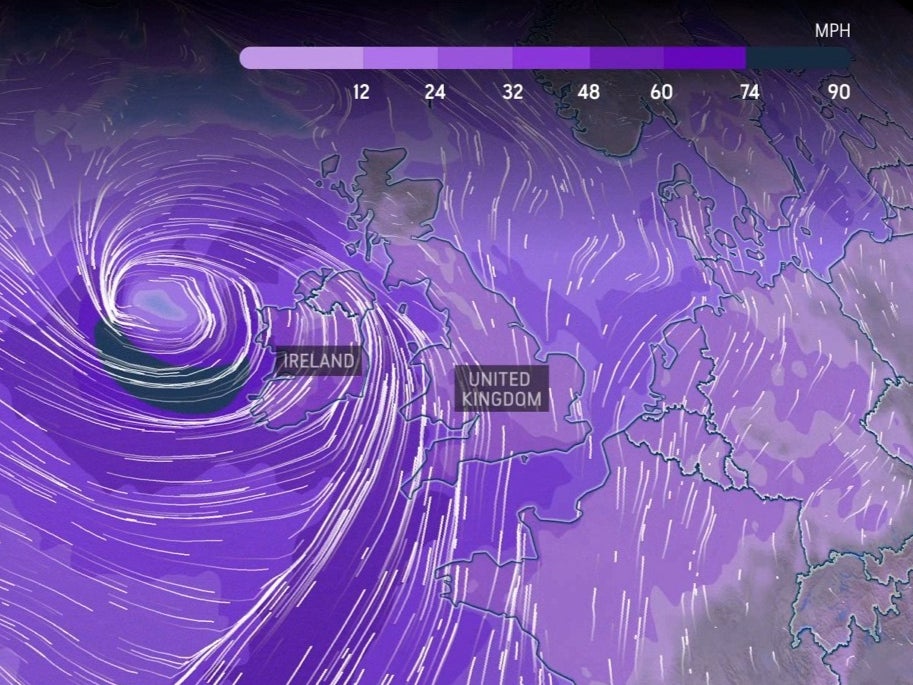

Storm Eowyn tracker live: Rare ‘stay at home’ weather warning issued as dangerous 113mph winds pose threat to life

Schools have been closed and people warned not to travel on Friday, as 100mph winds are set to pose a danger to life in parts of the UK.

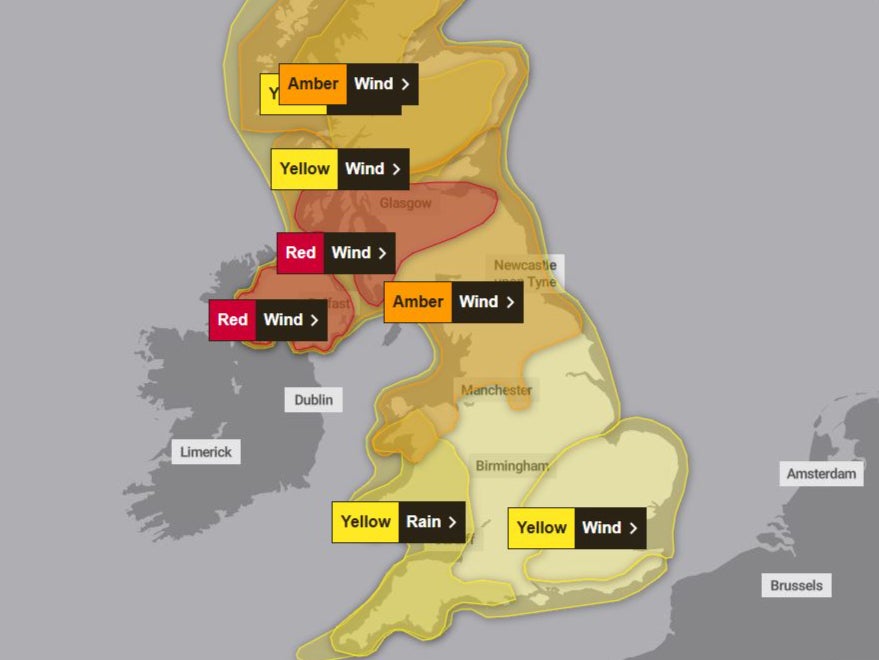

Rare red weather warnings will become active in Northern Ireland from 7am on Friday as Storm Eowyn is likely to damage buildings, uproot trees and cause power cuts, the Met Office said.

The warning will spread to Scotland at 10am, while amber and yellow warnings are in place across the rest of the UK on Friday.

Hundreds of schools will close, all trains in Scotland will be suspended, and police have warned people not to travel on Friday in areas under the rare red “danger to life” weather warning for high winds.

British Airways has grounded more than 20 flights.

The Met Office said winds would pick up rapidly during Friday morning’s rush hour, bringing peak gusts of 80-90mph, and up to 100mph along some exposed coasts.

Police said no road users should travel in or to the red weather warning area, and motorists there were advised not to drive unless absolutely essential.

Some 4.5 million people received emergency alerts on their phones warning of the incoming storm in the “largest real life use of the tool to date” on Thursday.

‘Ppowerful bomb cyclone’ to hit UK and Europe

The storm poised to hit Scotland and Northern Ireland is predicted to be a “powerful bomb cyclone”.

A storm is considered a bomb cyclone when the barometric pressure falls at least 0.71 of an inch of mercury (24 millibars) in 24 hours, a measure that could be more than doubled by this storm’s intensification, AccuWeather says.

AccuWeather lead international forecaster Jason Nicholls said: “Storm Eowyn is expected to produce wind gusts of 90mph to 110 mph across parts of Ireland and the UK.

“Powerful winds will reach northwestern Spain, northwestern France, Denmark and southern Norway through Saturday.

“Destructive wind gusts could lead to power outages, travel delays and business disruptions. Flying debris is a serious risk to people and structures.”

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 06:55

How rare are red weather warnings and what is the danger?

Red weather warnings are the rarest kind, issued when conditions pose a danger to life:

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 06:00

Most dangerous storm in Irish history

Ireland is set to face one of the most dangerous storms in its history, with wind speeds of up to 80mph inland across the country.

The National Emergency Co-ordination Group said Storm Eowyn would be one of the “most severe” Ireland has experienced.

Keith Leonard, the group’s chairman, said it would be “destructive, dangerous and disruptive”.

Met Eireann warned of storms of “incredible intensity”.

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 05:15

Much of England and Wales will have hazy sunshine on Friday, while Scotland suffers winds of 90mph, forecasters say.

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 03:40

Main coastal lines to close

Network Rail said it has taken “the difficult decision” to close the West Coast Main Line north of Preston and the East Coast Main Line north of Newcastle for much of Friday.

Passengers on the East Coast main line, which links London King’s Cross with northeast England and Scotland, will face disruption all weekend.

On Friday passengers are advised not to travel north of York.

Passengers booked on LNER can use their tickets for Friday any time up to Monday – but at the weekend London-Peterborough is closed for engineering work.

Lisa Angus, of Network Rail, said: “We have been preparing for the severe impacts of Storm Eowyn all week and will have scores of workers ready to deal with any incidents which occur, such as flash flooding or fallen trees and other items blocking the tracks.

“We ask residents living by the railway to tie down loose garden items, like trampolines or gazebos, which pose a risk of blowing onto the railway and could cause further unnecessary delays for passengers and freight services.”

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 02:05

Blast from the past

Remember Storm Ashley, Storm Bert or Storm Darragh? Catch up on all the weather warnings for fog, winds, snow, ice, flooding and storms since 2023 here.

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 01:05

All of the UK will be battered by high winds, but Scotland and Northern Ireland in particular, the Met Office says.

Jane Dalton24 January 2025 00:20

In pictures: Storm approaching

Jane Dalton23 January 2025 23:20

Castles and National Trust centres to close

The National Trust for Scotland says many of its attractions will be closed on Friday and Saturday, and Historic Environment Scotland says several castles will close, including Edinburgh and Stirling.

The whole of the UK is covered by at least one yellow weather warning on Friday, with warnings for snow, wind and rain in place, as it braces for the effect of the fifth named storm of the season.

An amber warning covers the south of Scotland and most of the central belt on Friday until 9pm.

A yellow wind warning is also in place for the whole of Scotland throughout Friday, and a yellow warning for snow covering much of the country runs from 3am until noon.

Jane Dalton23 January 2025 22:25

Forth Road Bridge set to shut

Forecast winds of 80mph around the Forth bridges will close the Forth Road Bridge, road management firm Bear Scotland says.

The Queensferry Crossing and Clackmannanshire Bridge would also be closed to high-sided vehicles, motorcycles and cars with trailers or roof boxes, it said.

Meanwhile, west coast ferry operator CalMac has cancelled all services across its network.

Scotland’s transport secretary Fiona Hyslop warned of widespread disruption to the transport network.

She said: “I would urge people to follow police advice and avoid travel in the area affected by the red warning for wind. If you do need to travel, your journey is likely to be badly disrupted and there will likely [sic] be cancellations to rail, ferry and air services.”

Jane Dalton23 January 2025 21:40

Politics

Patrick Christys: I love Great Britain, but our politicians and authorities are making it unbearable

I love Great Britain. But today, Great Britain hit rock bottom.

The walking, talking advert for the death penalty, Axel Rudakubana, was sentenced for the Southport massacre.

He showed no remorse. He kicked off in the dock. And he is evil personified.

But how was he allowed to do this? Caught with a knife 10 times, reeported to Preevent 3 times, he called ChildLine and said he wanted to kill someone, they called the police, the police went round and didn’t do anything.

Patrick Christys says Britain HAS to get a grip

GB NEWS

The authorities have blood on their hands.

But as Britain’s biggest monster began his 52-year prison sentence today, I looked around at the other news.

A man in a balaclava allegedly stabbed five people in Croydon today.

Last night when I got home I saw about a stabbing spree in Plymouth – a 40-year-old woman died. The suspect is still on the run.

Look at The Sun today – A 12-year-old boy was walking through a park in Birmingham and was stabbed in the stomach.

A 14-year-old boy has been arrested on suspicion of his murder.

Axel RudakubanaPA

Axel RudakubanaPA

Yesterday, a man admitted killing his ex-girlfriend and her sister with a crossbow and their mother with a knife after he broke into their home.

Paedophiles caught with hundreds or even thousands of indecent images of children are not being sent to prison. They’re allowed back out onto the streets to just live their lives.

This is ridiculous.

A man was caught with a loaded AK-47 in Leeds – he had 30 rounds of live ammunition. He got 5 years in prison, he’ll be out in two and a half.

We’ve got illegal immigrants running rampant – one in 12 people in London are here illegally.

Just today an asylum seeker driving an uninsured vehicle was sent to prison after he smashed into a nurse and broke her spine three weeks before her wedding.

That’s before I’ve mentioned the catalogue of asylum seeker rapists that we have over here.

There was one bit from today’s sentencing of Axel Rudakubana that stood out to me as well.

The judge there, despite everything we heard in court today, at pains to say Axel Rudakubana wasn’t to blame for the summer disorder.

Well I think he was, now I’m not condoning the torching of a migrant hotel or any of that stuff but whether Rudakubana is to blame or not is irrelevant – it’s ALL of it, isn’t it!

It’s all of it. Every day we see news stories like the ones I’ve rattled off here.

Every day we get damning figures, like this morning the Home Office revealing the number of foreign national offenders living in the UK has tripled in the last seven years.

Or two thirds of sexual assaults in London being committed by foreigners.

It’s all of it! It’s every day. And it’s so avoidable. Don’t let wrong’uns into the country. Deport the ones we have now. Don’t miss all the warning signs from a lunatic like Axel Rudakubana who has literally screamed the fact he was going to be a serial killer from the age of about 13.

Our politicians should hang their heads in shame for all the crime we have but our authorities should do for everything.

I love Great Britain – but they are making it unbearable.

We have to get a grip.

NewsBeat

Russia suffering ‘environmental catastrophe’ after oil spill in Kerch Strait

BBC Verify

Reuters

ReutersSatellite images reviewed by BBC Verify have shown a major oil slick spreading across the Kerch Strait that separates Russia from annexed Crimea, a month after two oil tankers were badly damaged in the Black Sea.

Oil has leaked into the strait from two ships which ran into trouble during bad weather on 15 December. Volgoneft-239 ran aground following the storm, while Volgoneft-212 sank.

Up to 5,000 tonnes of oil has now leaked, and media reports and official statements analysed by BBC Verify suggest the spill has spread across the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

A senior Russian scientist called the spill the country’s worst “environmental catastrophe” of the 21st Century.

“This is the first time fuel oil has been spilled in such quantities,” Viktor Danilov-Danilyan – the head of science at the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) – said in a 17 January interview with a Russian newspaper.

Russian scientists said in December that this spill could be more than twice the size of a similar disaster in the strait in 2007, which saw up to 1,600 tonnes of heavy oil leak into the sea. Ukraine’s ministry of ecology has estimated that the clear up from the latest spill could cost the Russian state up to $14bn (£11.4bn).

Paul Johnston, a scientist at Greenpeace Research Laboratories, said “there’s always an element of uncertainty around oil spills”, but a lack of timely information has heightened this uncertainty further.

“I’m not entirely optimistic we’ll ever know the full extent of the problem,” he added.

Satellite images reviewed by BBC Verify on 10 January – the most recent available high-resolution photos – showed a massive oil slick running through the strait, measuring at least 25km (15 miles) long. A second, smaller slick measuring around 5.7km (3.5 miles) long is also visible.

Mr Danilov-Danilyan said that oil could “by late January reach Odesa” in southern Ukraine and “one cannot rule out” it travelling as far as the coasts of Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey.

In a statement to BBC Verify, a spokesperson for Greenpeace said the group estimated that oil from the spill now covered an area totalling up to 400 sq km.

The spill appears to have moved quickly after the initial incident. On 24 December, satellite images reviewed by BBC Verify showed oil accumulating on a beach in Anapa – some 40 miles from the strait.

BBC Verify has analysed reports in Russian media, statements from officials and Greenpeace releases from this month that talk about oil being found or cleared up on various beaches.

The reports suggest that the oil has now spread as far north as the occupied city of Berdyansk in Ukraine and as far south-west as Lake Donuzlav on the Crimean Peninsula, which Russian illegally annexed in 2014.

The leak involves heavy M100-grade fuel oil that solidifies at a temperature of 25 degrees Celsius.

A Greenpeace spokesperson told the BBC that M100 doesn’t stay on the water’s surface for long. Once underwater, it is “technically impossible to neutralise”, and can take decades to be biodegraded by marine micro-organisms.

Footage recorded by the Russian NGO The Earth Touches Everyone and included below appeared to show large amounts of heavy oil accumulating on the seabed.

The Earth Touches Everyone

The Earth Touches EveryoneSome experts have warned that the leak has heavily impacted marine life in the region. Footage authenticated by BBC Verify has shown birds covered in oil.

It is not known exactly how many animals have been harmed by the spill.

Overall, Russian officials say about 6,000 birds have been delivered to “rehabilitation centres” on the Russian mainland, but it is unclear how many of them will survive. A local bird sanctuary in Stavropol territory said of 1,051 birds affected by the oil spill that have been delivered to them only about 17% have survived.

Reuters

ReutersGreenpeace told BBC Verify that the final number of dead birds could be far higher, citing the 12,000-13,000 killed by the 2007 spill in the strait.

A dolphin rehabilitation centre in Russia’s Krasnodar Territory told Interfax news agency that around 70 dead dolphins have been discovered on the shores following the latest oil spill.

“This is a horrific blow to the ecosystem,” Mr Danilov-Danilyan told Russia media. He predicted the death of “tens of thousands of birds, many dolphins, [and] big losses in the coastal flora and fauna”.

“Practically nothing, other than microorganisms that feed on fuel oil and break it up, can live in that sort of environment, even in salt water. The removal of 200,000–500,000 tonnes, at least, of contaminated soil too will not go without consequences, and will certainly lead to a reshaping of the coast,” he said.

Dmitry Lisitsyn, Executive Fellow at Yale University’s School of the Environment, told BBC Verify that under Russian safety regulations these types of tankers are barred from leaving rivers in winter.

“Those ships are not intended for high waves, they are very long with a shallow draught,” he said.

Questions have also been raised about the seaworthiness of the vessels, which are both over 50 years old, according to Marine Traffic.

Footage released by Russian authorities showed the bow of one tanker completely broken off during the incident, with streaks of oil visible in the water. The captains of both vessels have been arrested and criminal investigations have been opened into the incident.

Ukrainian activists have accused the ships of being part of Russia’s so-called shadow oil fleet. Moscow has been accused of using the so-called ghost fleet of tankers, which are often poorly maintained and lack proper insurance, to move oil and circumvent sanctions, though analysts the BBC has spoken to could not confirm the claims.

Experts say the long-term fallout from the spill may not be limited to just Russia.

“In general, Russia has suffered more than any other country so far from the Kerch Strait accident,” Dmitry Markin of Greenpeace said.

“However, the majority of the leaked fuel oil is still in the sea. Therefore, the long-term consequences for the occupied territories of Ukraine may be no less severe.”

Graphics by Erwan Rivault.

NewsBeat

Starmer unlikely to be ruffled by Trump – but he must keep his party in line | Politics News

From shattering the record for most executive orders signed on a first day in office, a bishop imploring him to have mercy on immigrants and LGBTQ+ people, Melania’s hat and Mark Zuckerberg’s wandering eye – the first few days of Trump 2.0 has been not just the talk of the town in Washington DC, but in Westminster too.

President Trump himself said as he took the mantle of 47th president of the United States that he wants to make his second term “the most consequential in US history”.

What is becoming even more clear as campaigning gives way to governing is that Trump 2.0 could prove vastly consequential for us too.

👉 Click here to listen to Electoral Dysfunction on your podcast app 👈

Talk to those around Whitehall and in the government, and there is a quiet acknowledgement of the ill-wind that is blowing from America towards liberals like Sir Keir Starmer as President Trump pulls out of climate accords, ramps up the war on purging government workers in diversity, equity and inclusion roles, and begins to roll out an aggressive immigration crackdown from mass deportations to a broad ban on asylum.

But what you will see in the coming weeks, is a pointed effort on the part of the government to neither comment nor engage on US domestic issues. This is likely to infuriate liberals and progressives both in the Labour Party and voter base, but when it comes to Trump 2.0 pragmatism reigns.

This is partly, say those in government, because of the difference in the win this time around.

Trump not only won the Electoral College, he won the popular vote – the first time a Republican candidate has won both in 20 years – and control of the House of Representatives and Senate. That gives a legitimacy and power that he didn’t have last time around and that momentum looks set to stay, at least until the mid-terms in two years’ time.

It is also because the Labour government, and wider Europe, needs Trump onside.

On the big issues facing the government, the US looms large, be it on economic growth – tariffs and trade deals – or security – Ukraine and the Middle East.

Whether you love or loathe Donald Trump, the decisions he takes on how to handle Israel, Gaza and Iran or bring about peace in Ukraine matters to us, and that means pragmatism must reign and punches pulled when it comes to the deep ideological divisions that are so obvious between Donald Trump’s politics and that of Keir Starmer.

We are entering more turbulent times and one very senior political figure admits it is going to be “rocky”.

They say this is because we find ourselves in a period where the organising principle for western foreign policy – the rules-based international order – is in quick retreat, as the US and Europe struggle to contain territorial and political ambitions of authoritarian countries like Russia and China.

Tricky terrain to navigate, the four priorities Starmer will want to try to land with President Trump when he gets an audience in the coming weeks are – Ukraine, the Middle East, tariffs and trade.

On the first, the contours of a plan are being discussed but the challenge is to get Putin to the negotiating table.

Russia, aware that President Trump is unwilling to keep pouring military aid into Ukraine, will want to carry on for as long as possible.

The task for allies is to persuade President Trump to go in hard on Putin so he is forced to the table in a position of discomfort.

We saw some of this from President Trump this week as he warned Putin of punishing sanctions on Russia should Moscow refuse to negotiate.

But there will be demands for Ukraine too, not least an expectation from President Trump that in return for US military support, President Zelenskyy must send younger Ukrainian men to the battlefield and lower the conscription age from 25 to perhaps as young as 18.

This will be incredibly difficult for President Zelenskyy and the Ukrainian people who have already sacrificed so much in a war they did not ask for and didn’t want.

As part of any ceasefire deal, expect the UK to be involved in a European peacekeeping force.

Expect too for Trump to ramp up pressure on NATO countries to boost defence spending from 2% of GDP to 3% or more (Trump called for the defence spend baseline of NATO members to be 5% in recent weeks).

Needless to say, the US’s handling of the Ukraine war and our role in that will be critical to not just our foreign policy, but national conversation in the coming months.

When it comes to the Middle East, the situation is trickier still.

I’m told there is some concern with the Foreign Office that Israel could make the case to Trump that the depletion of Iran’s proxies – Hezbollah and Hamas – make this a moment to target Iran.

There is nervousness that Trump, who has long made his acute dislike of Iran clear (last time around he abandoned the Obama nuclear deal with Tehran), buys into that and escalates a wider conflict in the region.

Even the risk of the US green-lighting a direct attack from Israel on Iran will only serve to accelerate Tehran’s nuclear programme.

Where Starmer is hoping to make some progress is on trade.

President Trump, a big Brexit and Boris Johnson backer, talked up a US-UK trade deal in his first term, only for President Biden to put it on the backburner.

Now, the UK government is hoping there will be some sectoral deals in which our two countries can improve trading relations in return for the UK offering President Trump perhaps assurances around his security concerns regarding China (you might remember back in 2020, pressure from the US prompted the the government to U-turn on allowing Huawei to have a role in its new generation of 5G networks).

How this plays out, even as the Labour government looks to build trading ties with Beijing, will be something to watch.

One obvious question will be – can the UK benefit from renewed UK-China trade ties without annoying Trump?

The final big issue for the UK is tariffs, but for now it doesn’t look like Trump is taking aim at the UK.

Instead, he has this week announced he’s considering imposing a 10% tariff on Chinese-made imports as soon as 1 February.

Starmer needs it to stay that way, given his plan for “national renewal” hinges on economic growth – which is looking precarious even without the prospect of tariffs on exports to the US.

Analysts had warned that a blanket 10% tariff could cost British industry $3bn (£2.5bn) a year, with cars, aerospace, pharmaceuticals and machinery among the sectors to be hardest hit.

One area where the government is more quietly confident is on the matter of its pick for ambassador, Lord Mandelson.

While rumours have been flying around that the architect of New Labour and former EU trade commissioner might get vetoed by President Trump, sources in government expect him to be appointed, and believe his nous as a political operator, coupled with his expertise in trade negotiations, make him a good choice.

But the bigger question is whether he can become a Trump whisperer in replacing current ambassador, Karen Pierce, who is well-regarded and liked by the Trump team.

How to handle Trump will undoubtedly be a test for Starmer, not just in his direct dealing but in the ripple effects of the Trump White House on British politics and his own supporters.

What goes in his favour is that he deals in facts not emotions, so is unlikely to be ruffled with whatever Trump and his allies throw at him.

His bigger challenge will perhaps be keeping the rest of his party in line when he wants pragmatism rather than principle to rule the special relationship.

NewsBeat

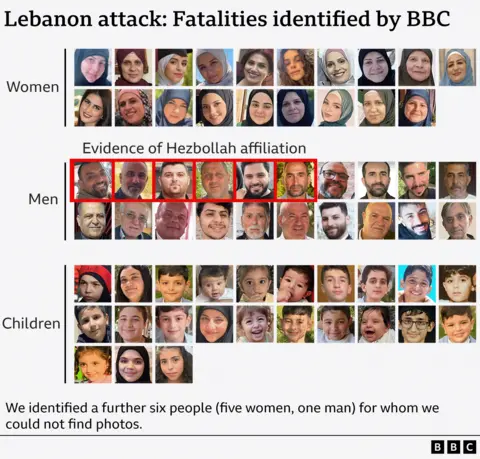

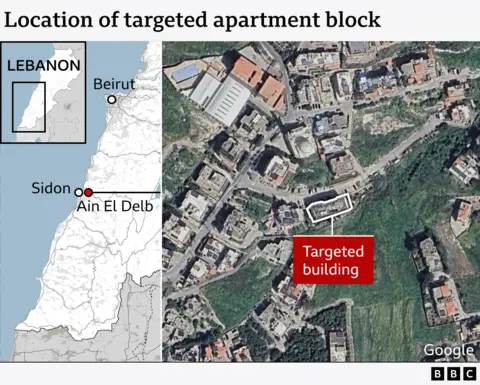

Mostly civilians died in IDF attack on Lebanon village, BBC finds

Senior international investigations correspondent, BBC World Service

BBC

BBCJulia Ramadan was terrified – the war between Israel and Hezbollah was escalating and she’d had a nightmare that her family home was being bombed. When she sent her brother a panicked voice note from her apartment in Beirut, he encouraged her to join him in Ain El Delb, a sleepy village in southern Lebanon.

“It’s safe here,” he reassured her. “Come stay with us until things calm down.”

Earlier that month, Israel intensified air campaigns against Hezbollah in Lebanon, in response to escalating rocket attacks by the Iran-backed armed group which had killed civilians, and displaced tens of thousands more from homes in northern Israel.

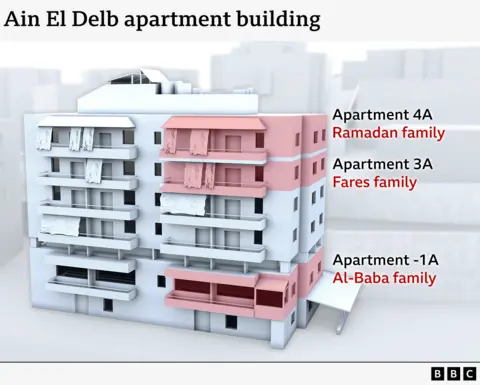

Ashraf was confident their family’s apartment block would be a haven, so Julia joined him. But the next day, on 29 September, it was subject to this conflict’s deadliest single Israeli attack. Struck by Israeli missiles, the entire six-storey building collapsed, killing 73 people.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) says the building was targeted because it was a Hezbollah “terrorist command centre” and it “eliminated” a Hezbollah commander. It added that “the overwhelming majority” of those killed in the strike were “confirmed to be terror operatives”.

But a BBC Eye investigation verified the identity of 68 of the 73 people killed in the attack and uncovered evidence suggesting just six were linked to Hezbollah’s military wing. None of those we identified appeared to hold a senior rank. The BBC’s World Service also found that the other 62 were civilians – 23 of them children.

Among the dead were babies only a few months old, like Nouh Kobeissi in apartment -2B. In apartment -1C, school teacher Abeer Hallak was killed alongside her husband and three sons. Three floors above, Amal Hakawati died along with three generations of her family – her husband, children and two granddaughters.

Ashraf and Julia had always been close, sharing everything with each other. “She was like a black box, holding all my secrets,” he says.

On the afternoon of 29 September, the siblings had just returned home from handing out food to families who had fled the fighting. Hundreds of thousands of people in Lebanon had been displaced by the war.

Ashraf was in the shower, and Julia was sitting in the living room with their father, helping him upload a video to social media. Their mother, Janan, was in the kitchen, clearing up.

Then, without warning, they heard a deafening bang. The entire building shook, and a massive cloud of dust and smoke poured into their apartment.

“I shouted, ‘Julia! Julia!,’” says Ashraf.

“She replied, ‘I’m here.’

“I looked at my dad, who was struggling to get up from the sofa because of an existing injury to his leg, and saw my mother running toward the front door.”

Julia’s nightmare was playing out in real life.

“Julia was hyperventilating, crying so hard on the sofa. I was trying to calm her down and told her we needed to get out. Then, there was another attack.”

Video footage of the strike, shared online and verified by the BBC, reveals four Israeli missiles flying through the air towards the building. Seconds later, the block collapses.

Ashraf, along with many others, was trapped under the rubble. He began calling out, but the only voice he could hear was that of his father, who told him he could still hear Julia and that she was alive. Neither of them could hear Ashraf’s mother.

Ashraf sent a voice note to friends in the neighbourhood to alert them. The next few hours were agonising. He could hear rescuers sifting through the debris – and residents wailing as they discovered loved ones dead. “I just kept thinking, please, God, not Julia. I can’t live this life without Julia.”

Ashraf was finally pulled from the rubble hours later, with only minor injuries.

He discovered his mother had been rescued but died in hospital. Julia had suffocated under the rubble. His father later told him Julia’s last words were calls for her brother.

In November, a ceasefire deal was agreed between Israel and Hezbollah with the aim of ending the conflict. The deal gives a 60-day deadline for Israeli forces to withdraw from southern Lebanon and for Hezbollah to withdraw its forces and weapons north of the Litani River. As this 26 January deadline approaches, we sought to find out more about the deadliest single Israeli attack on Lebanon in years.

In the apartment below Julia and Ashraf’s, Hawraa and Ali Fares had been hosting family members displaced by the war. Among them was Hawraa’s sister Batoul, who, like Julia, had arrived the previous day – with her husband and two young children. They had fled intense bombardment near the Lebanon-Israel border, in areas where Hezbollah has a strong presence.

“We hesitated about where to go,” says Batoul. “And then I told my husband, ‘Let’s go to Ain El Delb. My sister said their building was safe and that they couldn’t hear any bombing nearby.’”

Batoul’s husband Mohammed Fares was killed in the Ain El Delb attack. A pillar fell on Batoul and her children. She says no-one responded to her calls for help. She finally managed to lift it alone, but her four-year-old daughter Hawraa had been fatally crushed. Miraculously, her baby Malak survived.

Fares family

Fares familyThree floors below Batoul lived Denise and Moheyaldeen Al-Baba. That Sunday, Denise had invited her brother Hisham over for lunch.

The impact of the strike was brutal, says Hisham.

“The second missile slammed me to the floor… the entire wall fell on top of me.”

He spent seven hours under the rubble.

“I heard a voice far away. People talking. Screams and… ‘Cover her. Remove her. Lift the stone. He’s still alive. It’s a child. Lift this child.’ I mean… Oh my God. I thought to myself, I’m the last one deep underground. No-one will know about me. I will die here.”

When Hisham was finally rescued, he found his niece’s fiance waiting to hear if she was alive. He lied to him and told him she was fine. They found her body three days later.

Hisham lost four members of his family – his sister, brother-in-law and their two children. He told us he had lost his faith and no longer believes in God.

To find out more about who died, we have analysed Lebanese Health Ministry data, videos, social media posts, as well as speaking to survivors of the attack.

We particularly wanted to interrogate the IDF’s response to media – immediately following the attack – that the apartment block had been a Hezbollah command centre. We asked the IDF multiple times what constituted a command centre, but it did not give clarification.

So we began sifting through social media tributes, gravesites, public health records and videos of funerals to determine whether those killed in the attack had any military affiliation with Hezbollah.

We could only find evidence that six of the 68 dead we identified were connected to Hezbollah’s military wing.

Hezbollah memorial photos for the six men use the label “Mujahid”, meaning “fighter”. Senior figures, by contrast, are referred to as “Qaid”, meaning “commander” – and we found no such labels used by the group to describe those killed.

We asked the IDF whether the six Hezbollah fighters we identified were the intended targets of the strike. It did not respond to this question.

One of the Hezbollah fighters we identified was Batoul’s husband, Mohammed Fares. Batoul told us that her husband, like many other men in southern Lebanon, was a reservist for the group, though she added that he had never been paid by Hezbollah, held a formal rank, or participated in combat.

Israel sees Hezbollah as one of its main threats and the group is designated a terrorist organisation by Israel, many Western governments and Gulf Arab states.

But alongside its large, well-armed military wing, Hezbollah is also an influential political party, holding seats in Lebanese parliament. In many parts of the country it is woven into the social fabric, providing a network of social services.

In response to our investigation, the IDF stated: “The IDF’s strikes on military targets are subject to relevant provisions of international law, including taking feasible precautions, and are carried out after an assessment that the expected collateral damage and civilian casualties are not excessive in relation to the military advantage expected from the strike.”

It had earlier also told the BBC it had executed “evacuation procedures” for the strike on Ain El Delb, but everyone we spoke to said they had received no warning.

UN experts have raised concerns about the proportionality and necessity of Israeli air strikes on residential buildings in densely populated areas in Lebanon.

This pattern of targeting entire buildings – resulting in significant civilian casualties – has been a recurring feature of Israel’s latest conflict with Hezbollah, which began when the group escalated rocket attacks in response to Israel’s war in Gaza.

Between October 2023 and November 2024, Lebanese authorities say more than 3,960 people were killed in Lebanon by Israeli forces, many of them civilians. Over the same time period, Israeli authorities say at least 47 civilians were killed by Hezbollah rockets fired from southern Lebanon. At least 80 Israeli soldiers were also killed fighting in southern Lebanon or as a result of rocket attacks on northern Israel.

The missile strike in Ain El Delb is the deadliest Israeli attack on a building in Lebanon for at least 18 years.

Scarlett Barter / BBC

Scarlett Barter / BBCThe village remains haunted by its impact. When we visited, more than a month after the strike, a father continued to visit the site every day, hoping for news of his 11-year-old son, whose body had yet to be found.

Ashraf Ramadan, too, returns to sift through the rubble, searching for what remains of the memories his family built over the two decades they lived there.

He shows me the door of his wardrobe, still adorned with pictures of footballers and pop stars he once admired. Then, he pulls a teddy bear from the debris and tells me it was always on his bed.

“Nothing I find here will make up for the people we lost,” he says.

Additional reporting by Scarlett Barter and Jake Tacchi

Politics

Chopper's Political Podcast: UK terrorism agency needs reform says Tom Tugendhat after Rudakubana failings

Sit back, pour yourself a drink and join GB News Political Editor Christopher Hope at his regular table in a Westminster pub where he will discuss the latest insider political intrigue and gossip with everyone from popstars to politicians.

New episodes released every Friday.

NewsBeat

Britain’s biggest mortgage lender expects three interest rate cuts this year | Money News

The boss of Britain’s biggest mortgage lender has told Sky News he expects three interest rate cuts this year, bringing some relief to borrowers and mortgage holders.

Lloyds Banking Group chief executive Charlie Nunn said he anticipates rates will continue to fall gradually thanks to the resilience of household and business finances – but cautioned that the UK could expect low growth because of a relative lack of investment.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, he said: “We think there’ll be three rate cuts this year.

“Of course, most people choose to fix their mortgage for two to five years and the pricing on that has been relatively stable and we think that stability is likely to remain for the remainder of this year.

“Those that are on the fixed rates are in a good place, and for those that are on a variable rate, their mortgage is likely to continue to come down slowly with the base rate.

“For those that are remortgaging, they are likely to get a significant uptick depending on when they set their mortgage.”

As Britain’s longest-serving bank chief in charge of the largest retail lender with more than 27 million customers, Mr Nunn is well-placed to assess consumer sentiment and economic prospects at the start of the year.

He added: “The UK economy is what I would characterise as very resilient but relatively slow growth. And that’s first of all because household finances continue to strengthen – there are some customers struggling to make ends meet and we’re always focused on them – but actually, deposits and savings in households have increased 6% year-on-year, and cash flows for many businesses again have also strengthened in the last year.

“What we haven’t yet got is investment in growth, and we still have quite a tight labour market with quite high wage inflation.”

Read more from Sky News:

Southport killer jailed

Red weather warning over Storm Eowyn

Sainsbury’s to cut 3,000 jobs

Mr Nunn praised Chancellor Rachel Reeves and Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds for delivering a positive message about the UK’s prospects in Davos, where optimism about America has contrasted with gloom-consuming European prospects.

“The UK message here has been very positive,” he said. “We’ve got a sort of barbell going on, with colleagues in America being very positive post the inauguration of [Donald] Trump… while Europe is feeling quite negative in Davos, and the UK is building its own path really as a place that people want to invest.”

“The UK is well-placed, we think, relative to the rest of the world, but sentiment has been down in the last few months and people have been nervous about some of the changes that the chancellor made on taxes in the coming months.”

The Lloyds boss was sanguine about the impact of Mr Trump’s second term, saying what counts is what he does, rather than just what he says.

“He’s one of the most predictable politicians we track, what he did on Monday this week is exactly what he said he’d do,” he said. “So there’s no uncertainty, I think, about his priorities and what he sees as important for the US economy and the ‘US first’ mindset.

“The uncertainty has always been around the execution, if he does execute, to what extent and when. Our base case for this year is that Trump will be good for the US growth, it will probably slow down the global economy if he starts to apply tariffs.”

NewsBeat

How Chelsea’s Cole Palmer has inspired the kids of St Kitts

Chelsea and England forward Cole Palmer proudly wears the flag of St Kitts and Nevis on his boots to honour his family roots.

And it is having an impact on the Caribbean island of St Kitts, as BBC Sport found out when visiting to speak to local children – and to Prime Minister Terrance Drew.

READ MORE: Cole Palmer – made in the Caribbean

Politics

Former security minister urges Government to ‘improve’ Home Office scheme ‘not scrap it’

Home Office’s Prevent programme should be “improved” not scrapped, says former Security minister Tom Tugendhat as Axel Rudakubana was jailed for 52 years for attacking and killing children in Southport last year.

The Government has launched a review of the Prevent programme after it emerged Rudakubana was referred to Prevent three times between 2019 and 2021, yet went on to commit his bloody murders in July last year.

Tugendhat – who was Security minister between 2022 and 2024 – was asked on Chopper’s Political Podcast whether he felt that Prevent should be axed.

He replied: “No, I wouldn’t. I would improve it.”

Home Office’s Prevent programme should be “improved” not scrapped, says former Security minister Tom Tugendhat as Axel Rudakubana was jailed for 52 years for attacking and killing children in Southport last year

Getty/ GB News

Tugendhat urged ministers to implement the recommendations in a review of Prevent by Sir William Shawcross.

He told today’s Chopper’s Political Podcast: “I would look at the Shawcross report – there’s a huge amount in there that we were able to get done. And there’s bits that we weren’t able to get done because they take time to introduce.

“And part of it is about making sure you’re ‘triaging’ properly. So you’re getting stuff in line in the appropriate way and you’re responding appropriately.”

Tugendhat – who was Security minister between 2022 and 2024 – was asked on Chopper’s Political Podcast whether he felt that Prevent should be axed

GB News

He added: “We need to get better at identifying triggers, as it were, on people.

“And when people have radicalised themselves or been radicalised to find out where we’re going.

“That’s why the Prevent aspect is so important.”

Listen or watch Chopper’s Political Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or GB News’ YouTube channel.

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years agoThese ’90s fashion trends are making a comeback in 2025

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe Season 9 ‘ Game of Thrones’ is here.

-

Fashion8 years ago

Fashion8 years ago9 spring/summer 2025 fashion trends to know for next season

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Entertainment8 years agoThe old and New Edition cast comes together to perform You’re Not My Kind of Girl.

-

Sports8 years ago

Sports8 years agoEthical Hacker: “I’ll Show You Why Google Has Just Shut Down Their Quantum Chip”

-

Business8 years ago

Uber and Lyft are finally available in all of New York State

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Disney’s live-action Aladdin finally finds its stars

-

Sports8 years ago

Steph Curry finally got the contract he deserves from the Warriors

-

Entertainment8 years ago

Mod turns ‘Counter-Strike’ into a ‘Tekken’ clone with fighting chickens

-

Fashion8 years ago

Your comprehensive guide to this fall’s biggest trends

You must be logged in to post a comment Login