Warning: This article contains references to domestic abuse and stalking

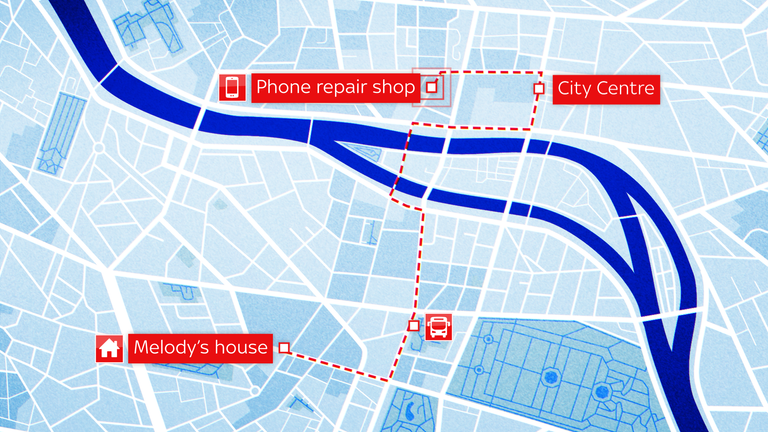

As Melody* got off the bus, her heart stopped. Her ex was charging towards her, a smirk on their face.

The city centre street was eerily empty and she felt panic clench at her chest as Alex* bore down on her.

Melody gestures an arm’s length in front of her: how close Alex came before veering away. “They were intensely staring at me – it was like they knew what they were doing.”

It wasn’t the first time this had happened. Alex was making a habit of turning up in places Melody hadn’t told anyone she would be, miles from where they lived. “I thought I’d been microchipped – like a cat. How else would they know so much about me?”

Alex was “coercive and controlling” during their relationship, Melody says. They forced her to move cities, micromanaged her life – even making her leave the door open when she used the toilet – and controlled what she ate, what she wore, and who she saw.

After they broke up, Alex still made their presence felt by appearing unexpectedly. Not knowing how her ex was tracking her left Melody living in fear. She knew what Alex would do to keep her under control and she had seen them get aggressive.

“I’ve never felt so frightened in all my life. The way this goes according to my domestic abuse support workers is: the next step they will kill you.”

Her phone battery had been draining faster than usual; she wondered if that could be linked to the tracking.

A trip to a phone repair shop uncovered a hidden app called mSpy that was feeding everything on Melody’s phone – including her exact location – to a remote dashboard, accessible to the person who installed it.

There was no icon to show her it was there. No notification to let her know she was being monitored.

“I felt like my entire life had been ripped from me,” she says. “They could see everywhere I’d been. Every person I’d spoken to. Everything in my diary. Stuff to the police and to court.”

mSpy is what is known as stalkerware: software covertly installed on someone’s phone so they can be monitored remotely.

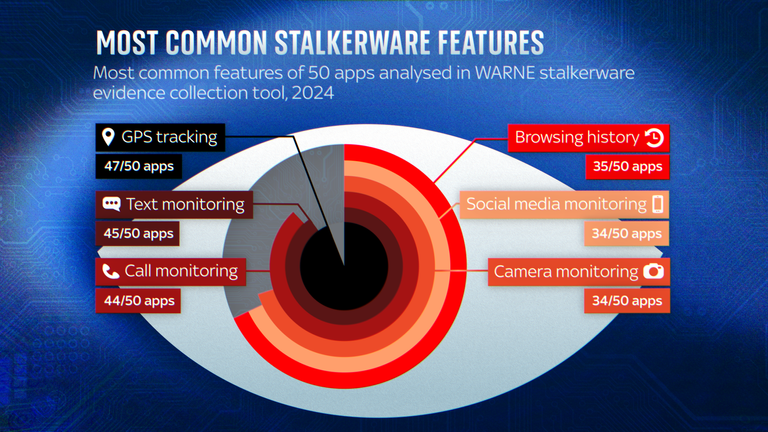

The most common features of these apps include tracking someone’s location, spying on messages and calls, remotely activating their camera and viewing social media and browsing history, according to researchers at Montreal’s Concordia University, who identify mSpy as stalkerware.

mSpy offers all these features – and more – but markets itself as “for parental control”. It cropped up in three lists of commonly detected stalkerware provided to Sky News by several cyber security companies. Of the 18 apps they flagged,14 are advertised as parental control software.

Advertising this way is a common tactic by stalkerware apps because it lets them skirt laws on covert surveillance, according to David Emm, a top researcher at cyber security company Kaspersky.

But there is also a booming market for legitimate parental control or “family tracking” apps – the kind that let you see your child’s location, limit their screen time and control their internet access.

Domestic abusers are increasingly using these apps, designed with children’s safety in mind, to monitor their partners, according to tech experts and domestic abuse frontline workers.

‘In the wrong hands they can be abused’

Being under surveillance has changed Caitlin’s* life: “I’ve moved house. My car’s changed, my job’s changed, kids’ schools have changed. I can’t go anywhere that I used to go.”

The monitoring started with Life360, a popular family tracking app that lets you share live locations. She says her ex convinced her to download it while she was pregnant, saying it was for her safety.

“It was only when I realised the app wasn’t being used for the right reasons that I started feeling unsafe,” Caitlin says.

Her ex monitored her every movement. If she wasn’t where he expected, she says, he would make her send photos to prove her whereabouts or show him receipts from the shops she had visited.

“I would get the silent treatment, or he would become quite violent,” she says.

Russell Kent-Payne, a cyber security expert, explains that apps such as Life360 are not “designed to be stalkerware… But in the wrong hands they can be abused.”

He adds: “It is something we are hearing reports of much more nowadays than we did several years ago.”

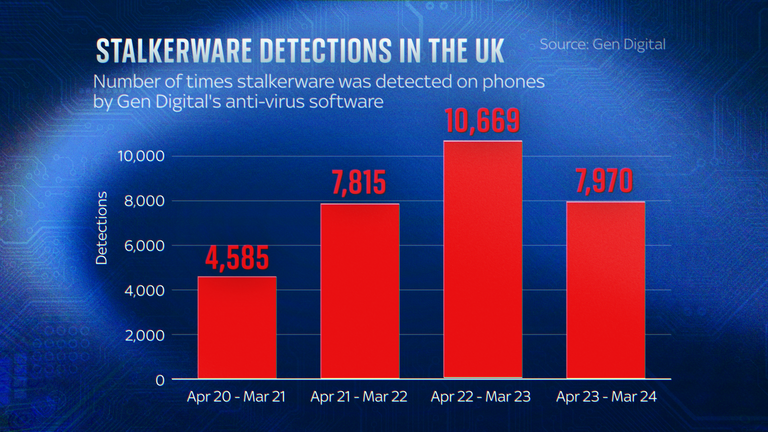

And data tells a similar story. Gen Digital, whose anti-virus products include Avast and Norton, said stalkerware increased globally by 239% between 2020 and 2023. It said parental control apps have become some of the most prevalent forms of stalkerware.

So when is something a parental control app, and when does it become a tool of abuse?

The key issue is consent, explains Eva Galperin, co-founder of the Coalition Against Stalkerware, which unites domestic abuse organisations and IT security companies combating tech abuse.

Software that hides on a phone is “de facto abusive”, she says. And someone in a coercively controlling relationship “agreeing” to download tracking software cannot be considered to be consenting.

Caitlin says her ex tried to stop her from having friends; she couldn’t even go for a walk without being interrogated. His abuse was “getting out of control”, she says – “but I didn’t realise at that point it was domestic abuse”.

Sky News contacted mSpy and Life360, but neither responded to questions about the allegations around how their technology is used by domestic abusers.

Experts say part of the problem is how normalised location-sharing apps have become.

It’s a “pernicious problem”, says Sara Kirkpatrick, chief executive of Welsh Women’s Aid. “We have sleepwalked into a situation where these things… can be used for malicious purposes.”

Tech abuse is no different from other types of abuse where “it’s the normal things that are weaponised”, she says.

Smart home tech, including ring doorbells and smart speakers, along with Bluetooth GPS trackers and apps that use location settings, offer more options for digital surveillance than ever before – even when products were not designed with that in mind.

The pace of development shows no sign of slowing – but there is little regulation to ensure the next generation of tech won’t be similarly exploited by abusers.

Emma Pickering, head of tech abuse at the domestic abuse charity Refuge, says this combination of factors creates a “ripe environment” for someone intent on tracking and abusing their partner.

Domestic violence affects more than two million UK adults. Charities report that 85% of them will have been subjected to some form of tech abuse, from GPS tracking to having their accounts hacked, receiving threatening messages and having intimate images shared online.

Difficult to get help

Tech abuse can make it near-impossible for somebody being monitored to get help.

Amy’s* ex was able to access everything on her phone by logging into her Apple ID on an iPad. When she found it under the sofa, she realised he had been able to access her message history, her bank accounts and email.

Being surveilled shrank her world and left her feeling “mute” and powerless. “Every little thing is monitored so you become nothing. You make sure there’s nothing to report.”

When Amy decided to leave the relationship, she couldn’t access the internet or use her phone to call for help.

It was only through secret meetings with her friend in a supermarket that Amy was able to plot her escape.

Leaving a relationship is statistically the most dangerous time for domestic abuse survivors.

Katy Brookfield, whose research focuses on how tech abuse impacts help-seeking, says there are few support options that don’t involve technology. If women can’t get help until they have left, that’s “very dangerous”, she says.

One of the markers of an app being stalkerware – rather than a legitimate parental control app – is that it is hidden on the target’s device. Rather than an app icon, it may be disguised behind a wifi symbol or Android logo so it blends in with preinstalled apps.

An app that does this cannot be considered an “ethical” parental control app – even if it advertises itself as such, according to researchers from University College London (UCL) and St Polten University of Applied Sciences in Austria.

Led by Eva-Maria Maier, they analysed parental control apps available via app stores and parental control apps that can be downloaded directly from app companies’ websites, known as “sideloading”.

Their research, shared with Sky News, reveals that sideloaded apps advertising themselves as parental control tools have features that suggest they could be used for partner surveillance.

As well as being hidden on devices – as 17 of the 20 analysed apps were – sideloaded apps requested more “dangerous” permissions, like letting the app access sensitive information or perform actions that were otherwise restricted, such as making the app hard to uninstall or by turning on a device’s camera.

The apps also offered extensive monitoring that you wouldn’t expect a parent to need for their child, the study said, including spying on dating apps that have an age limit of 18.

By comparison, Maier says the “green flags” for true parental control apps include notifications that the app is running in the background and clear data collection processes, as well as the makers not promoting “excessive” spying capabilities.

‘Not science fiction’

Melody wants to see apps like mSpy banned.

She says: “The way it’s marketed is towards kids and parental control. But you might as well give people who want to cause harm, stalk or harass a charter to do so, it’s so easily done. People seem to think that this is all science fiction and spy thrillers. It’s not. It’s real and it’s happening.

“There has to be some kind of regulation around these apps.”

Current legislation targets app users, rather than developers. While the apps themselves aren’t banned, installing software on someone else’s device without their consent is illegal under the Computer Misuse Act – although experts say the law is rarely used to prosecute domestic abuse cases.

Domestic Abuse Commissioner Nicole Jacobs wants to see tech companies forced to consider from the outset how their products might be “perverted and misused” – a process known as safety by design.

Dr Leonie Tanczer, an expert in gender and technology at UCL, says part of the problem is that developers will think about the threats posed by terrorists or nation states – but not intimate partners.

The commissioner says the onus needs to fall on government as well as tech companies, to make safety by design something that is enforceable.

“We need to get to a place where this would be a non-negotiable, that we can’t buy any tech or deal with any companies who aren’t really taking that safety by design seriously.”

Meanwhile, Melody is still dealing with the impact of being stalked. She barely uses her phone, changes her route with every trip out, and says she doesn’t feel safe even at home.

“I’m in therapy, just trying to deal with how this has affected every single aspect and part of my life. I don’t want to wish it on anyone at all.

“I ultimately want my life back.”

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of domestic abuse survivors.

If you suspect you are being abused and need to speak to someone, there are people who can help you.

The National Domestic Violence Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Refuge has resources for people suffering from tech abuse

Respect, the helpline for male domestic abuse victims: 0808 8010327

Galop, the LGBT+ anti-violence charity: 0800 999 5428

The Data and Forensics team is a multi-skilled unit dedicated to providing transparent journalism from Sky News. We gather, analyse and visualise data to tell data-driven stories. We combine traditional reporting skills with advanced analysis of satellite images, social media and other open source information. Through multimedia storytelling we aim to better explain the world while also showing how our journalism is done.

+ There are no comments

Add yours