Mudathir Ibrahim Suleiman

Mudathir Ibrahim SuleimanDr Mustafa Ali Abdulrahman Ibo and his colleagues bravely perform surgery under increasing bombardment in the last remaining hospital in el-Fasher, a city that has been under siege for the last nine months in Sudan’s western Darfur region.

Over the last month the hospital has recorded 28 deaths and more than 50 injuries among its staff and patients because of intense shelling. This is the highest number of casualties recorded in a month since the siege began.

“Recent continuous attacks targeting Saudi Hospital have intensified dramatically, it has become part of our daily lives,” Dr Ibo, a Darfuri who has lived in el-Fasher since 2011, told the BBC.

He said the most frightening day had been when a team of medics were performing an emergency caesarean as the shelling began – a near-death experience for them all.

”The first one hit the hospital’s perimeter wall… [then] another shell hit the maternity operating room, the debris damaged the electrical generator, cutting off the power and plunging us into complete darkness,” he said.

The surgical team had no option but to use the torches on their phones to finish the two-hour operation.

Part of the building had collapsed and the room was full of dust with shrapnel scattered all over the place.

Dr Khatab Mohammed, who had been leading the surgery, described the dangers.

“The situation was dire, the environment was no longer sterile,” the 29-year-old medic told the BBC.

“After ensuring our safety and the patient’s safety from shrapnel, we cleaned her and changed our surgical gowns since our clothes were full of dust and we continued the surgery,” he said, adding that the patient could have died from complications.

After successfully delivering the baby, the doctors moved mother and new-born to another room to recover and then gathered to take a group photo.

It was a testament to their survival, but Dr Mohammed added: “I thought it might be our last photo, believing that another shell would hit the same spot and we would all die.”

They went on to perform two more life-saving emergency operations that day.

Mudathir Ibrahim Suleiman

Mudathir Ibrahim SuleimanThese doctors – most of whom are graduates of the University of el-Fasher – have stayed put since Sudan’s civil war erupted in April 2023.

The conflict has pitted the army against the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and has caused the world’s biggest humanitarian crisis, forcing more than 12 million people from their homes.

The two rivals had been allies – coming to power together in a coup – but fell out over an internationally backed plan to move towards civilian rule.

A year into the conflict, the siege of el-Fasher began. It is the only city still under army control in Darfur, where the RSF has been accused of carrying out ethnic cleansing against non-Arab communities.

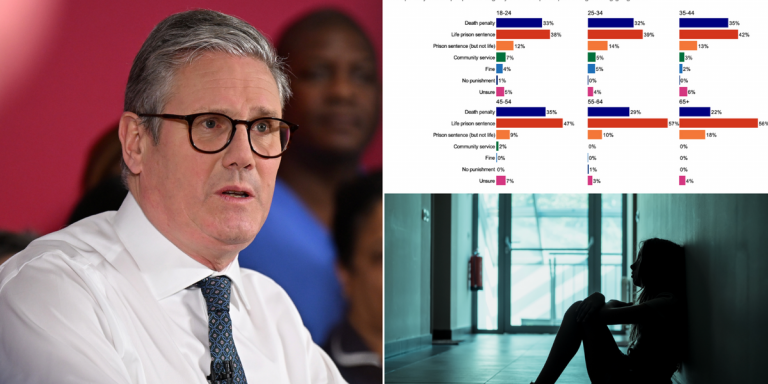

The RSF began attacking el-Fasher from three sides and cut off supply routes. In a report issued last month, the UN Human Rights Office said the fighting had left more that 780 civilians dead and more than 1,140 injured – many of them casualties of crossfire.

The fighting has forced all other hospitals in el-Fasher to shut.

South Hospital, which was supported by medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), was the main health facility in the city dealing with war casualties.

It was near the frontline and was stormed in June by RSF fighters, who also looted medicine and equipment and assaulted staff.

Saudi Hospital, which is run by the Ministry of Health and funded by non-governmental organisations, the UN and MSF, specialises in obstetrics and gynaecology but is now providing all medical services – it is the only place in North Darfur state with surgical capacity.

Amid shortages of medical supplies, equipment and personnel, Saudi Hospital is facing ”a heart-breaking situation that violates all humanitarian and international laws and values”, its medical director, 28-year-old Mudathir Ibrahim Suleiman, told the BBC.

He recalled how terrifying it was during recent bombings: “Pregnant women, children and staff were in shock and paralysis, some people were injured and had to be pulled out the rubble.

“All the current conditions push us to consider stopping our work, but women and children have no other place to save their lives except this hospital,” he said.

“The staff at the hospital are doing the impossible to save lives.”

All normal aspects of life have completely disappeared from el-Fasher, especially in the northern and eastern parts. The university, for example, operates via online learning, with exam centres established in safer cities like Kassala in eastern Sudan.

With widespread hunger and insecurity, the city has also emptied. About half the population have sought refuge in the nearby Zamzam camp, where an estimated 500,000 people now live in famine conditions.

Saudi Hospital also serves the camp, with MSF running ambulances to bring in emergency cases.

But these have also recently started coming under attack, including an incident earlier this month when a gunman shot at a “clearly marked ambulance with the MSF logo and flag”.

“We are horrified by this deadly attack on a humanitarian crew carrying out life-saving medical work where it’s desperately needed,” MSF’s Michel Olivier Lacharité said in a statement.

Mudathir Ibrahim Suleiman

Mudathir Ibrahim SuleimanDr Ibo admitted it was his colleagues – there are 35 doctors and 60 nurses at Saudi Hospital – who kept him going.

”We lose people every day, and offices and rooms are destroyed, but thanks to the determination of the young staff, we continue to persevere.

”We draw our resilience from the people of el-Fasher – we are its children and graduates of the University of el-Fasher.”

Aid agencies are warning that one of the worst maternal and child health emergencies is unfolding in Darfur, where some areas are also being targeted in air strikes by the military.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for a halt to attacks on health facilities and adherence to international humanitarian laws.

“The sanctity of health must be respected even in war,” WHO Sudan communications officer Loza Mesfin Tesfaye told the BBC.

Dr Mohammed, who is originally from Sudan’s White Nile State but came to el-Fasher to study medicine in 2014, also pays homage to his team, who have ignored many opportunities to flee.

“Our souls refused to abandon the people of this city – especially given the catastrophic conditions we witness daily.”

All the medics, who communicated via chats and voice notes on WhatsApp, sounded focused.

”We are determined to continue saving lives, from wherever we can, even underground or under the shade of a tree, we pray for the war to end and for peace to prevail,” said Dr Ibo.

Additional reporting by Sudanese journalist Mohammed Zakaria

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

+ There are no comments

Add yours