London Museum from 2015

London Museum from 2015From the end of the Roman occupation through the Anglo-Saxon and Viking invasions – a new way of testing DNA in ancient bones could force a rethink of key moments in Britain’s early history, say researchers.

Scientists could already track big alterations in DNA that occur over thousands or millions of years, helping us learn, for example, how early humans evolved from ape-like creatures.

Now researchers can identify subtler changes over just hundreds of years, providing clues as to how people migrated and interacted with locals.

They are using the new method to analyse human remains found in Britain, including from the time when Romans were replaced by an Anglo-Saxon elite from Europe.

Prof Peter Heather, from Kings College London, who is working on the project with the developers of the new DNA technique at the Francis Crick Institute in London, said the new technique could be “revolutionary”.

While the project will analyse the DNA of more than 1,000 ancient human remains of people who lived in Britain during the past 4,500 years, researchers have homed in on the time after the Romans left as a particularly interesting era to study.

What happened in this period more than 1,500 years ago is unclear from written and archeological records. Historians are divided in their views about the scale and nature of the Anglo-Saxon invasion, whether it was large or small, hostile or co-operative.

“It is one of the most contested and therefore one of the most exciting things to work on in the whole of British history,” according to Prof Heather.

“[The new method] will allow us to see the type of relations that are being found with the native population,” he said. “Are they co-operative, is there interbreeding, are the locals able to make their way into the elite?”

They are optimistic about the success of the technique, known as Twigstats, after testing it on human remains found in mainland Europe between the years 1 and 1,000 CE.

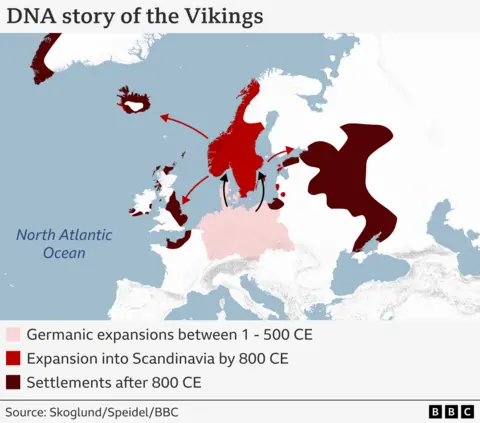

Much of what they gleaned from the DNA about the spread of the Vikings into Scandinavia tallied with historical records.

This result, published in the journal Nature, confirmed the method worked while showing how powerful it could be at shedding new light on accepted facts when findings didn’t match what was written in the history books.

“That was the moment we got really excited,” said Dr Leo Speidel, who developed the technique with his group leader Dr Pontus Skoglund. “We could see that this could really change how much we can find out about human history.”

The problem the researchers were trying to overcome is that a human’s genetic code is extremely long – consisting of 3 billion separate chemical units.

Spotting the small genetic changes in that code which occur over a few generations, for example, as a result of new arrivals interbreeding with the local population, is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

The researchers solved the problem by, as it were, taking away the haystack and leaving the needle in plain sight – they found a way to identify the older genetic changes, disregard them and look only at the most recent alterations.

They combed the genetic data of thousands of human remains from an online scientific database, then calculated how closely they were related to each other, which chunks of DNA were inherited from which groups and when.

This created a family tree with older changes appearing in earlier branches, and more recent changes showing up in newer ‘twigs’, hence the name Twigstats.

Francis Crick Institute

Francis Crick InstituteEach of the people whose remains will be studied have their own tales to tell and soon scientists and historians will be able to hear their stories, said Dr Skoglund.

“We want to understand many different epochs in European and British history, from the Roman period, when the Anglo-Saxons arrived, through the Viking period and see how this shapes the ancestry and diversity of this part of the World,” he said.

As well as showing up interbreeding with different populations, embedded in the ancient DNA are hugely important details on how people coped with key historical moments, such epidemics, shifts in diet, urbanisation, and industrialisation.

The technique can potentially be applied to any part of the world for which there are a large collection of well preserved human remains.

Prof Heather wants to use it to investigate what he describes as one of European history’s biggest mysteries: why central and eastern Europe changed from being Germanic speaking to Slavic speaking, 1,500 years ago.

“Historical sources show what was the case before and what was the case after, but there is nothing about what happened in between,” he said.

Follow Pallab on Blue Sky and X

The new series of Digging for Britain, featuring one of the Anglo-Saxon burial sites, Poulton Farm, will be available to watch on BBC iPlayer from 7th January 2025.

+ There are no comments

Add yours