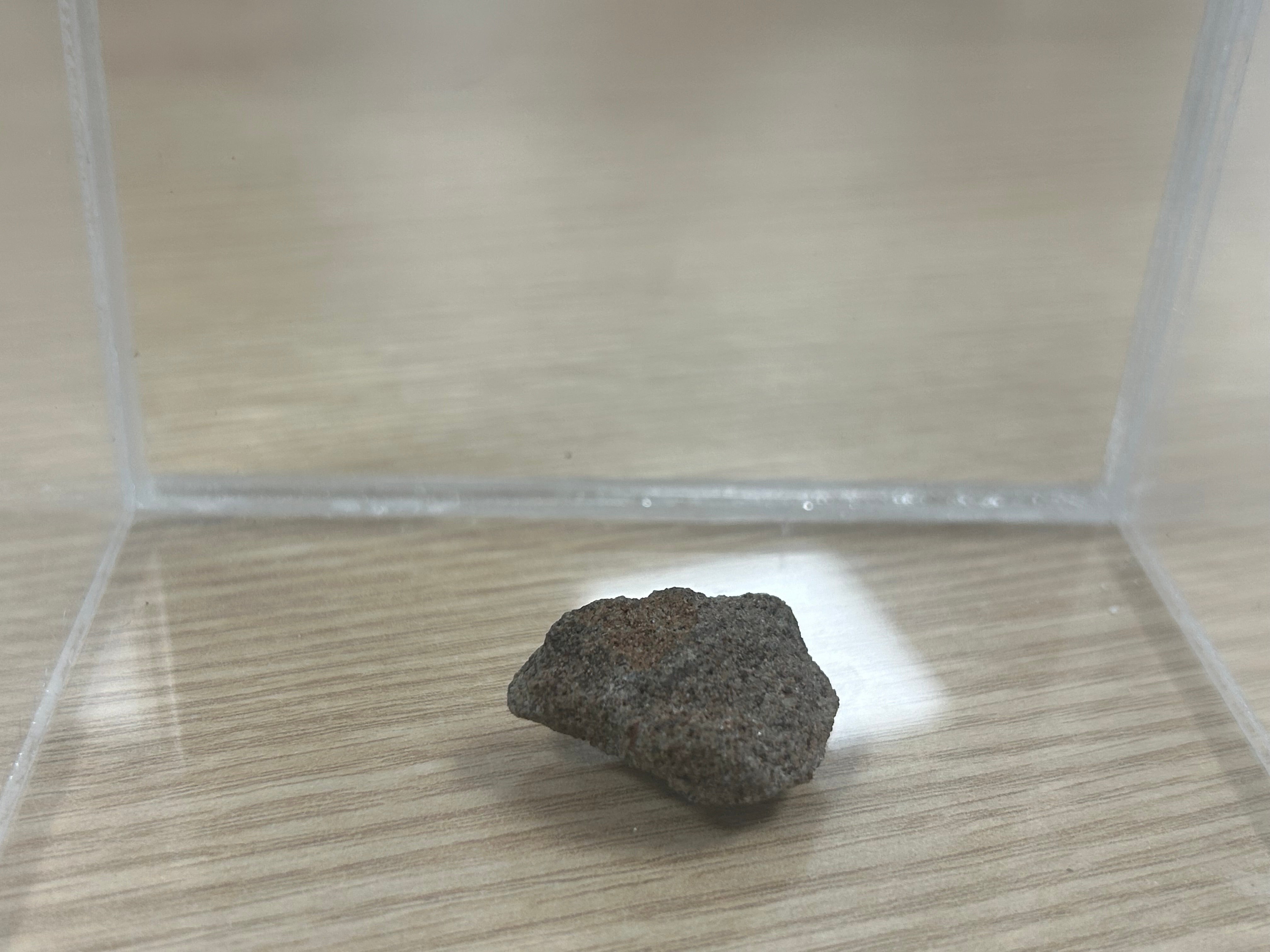

A search is underway for more than 30 fragments of the ancient Stone of Destiny after they separated from the ancient artefact following its famous theft from Westminster Abbey and secret repair.

The exact location of most of these small chips remains a mystery as they have been passed down through families or are in private collections.

Professor Sally Foster has been painstakingly collating the history of as many of the pieces as possible, some of which were “hidden in plain sight”, saying they form a fascinating new strand in the centuries-old history of the Stone of Scone.

Many of the fragments in question came about when a mason secretly repaired the stone after it split in two during the raid by four students in 1950.

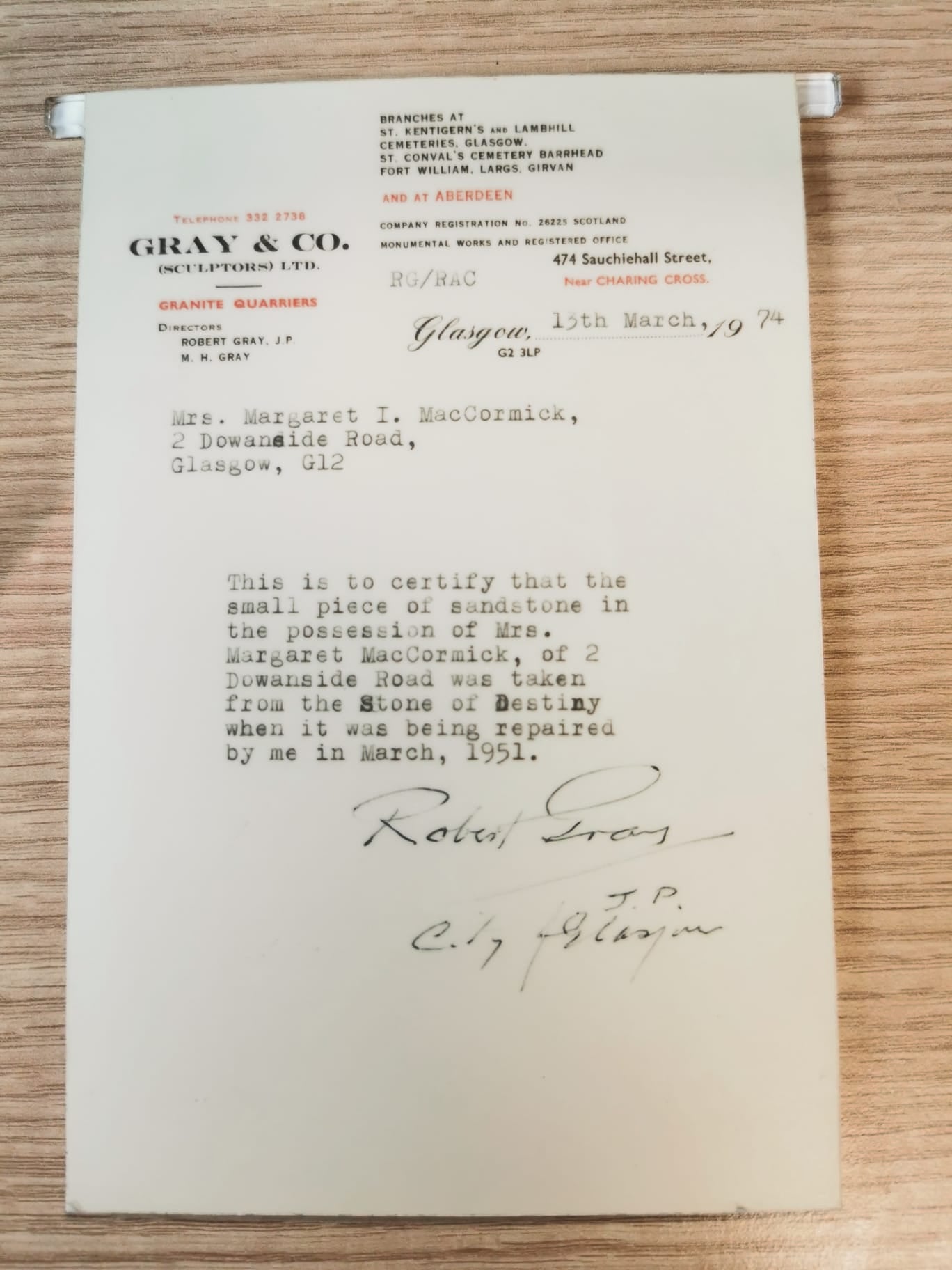

This work happened under the supervision of stonemason and nationalist politician Bertie Gray, who carefully numbered and recorded the pieces.

He passed them on to the four students who carried out the heist – as well as those he admired in and around the movement.

While the existence of fragments from the sandstone block returned in 1951 have been known – an inch-sized piece was gifted to Alex Salmond by Sir Neil MacCormick and was kept at SNP headquarters – it has not been widely appreciated that there are potentially more than 30 in existence.

Prof Foster believes Mr Gray’s repair work resulted in as many as 34 numbered fragments of the original stone.

The Commissioners for the Safeguarding of the Regalia – the body of senior officials charged with overseeing the Scottish crown jewels – are currently considering what should happen with the fragment gifted to Mr Salmond.

Prof Foster’s research, funded by the The British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust, has involved combing through old newspaper archives dating back decades.

It has revealed pieces of the stone in some surprising locations.

Other prominent nationalists to receive small chips include Margo MacDonald and Winnie Ewing – who had her piece fashioned into the centre of a brooch she once wore to an interview with the BBC’s David Frost.

Canadian journalist Dick Sanburn received chip number 25 in 1951 and proudly kept it behind his desk at the Calgary Herald. He said the fragments were “carefully numbered and recorded to prevent a flood of fakes”.

Former lord provost of Glasgow Sir Patrick Dollan displayed his chip to attendees at a concert in 1959.

As she continued her research project, titled Authenticity’s Child, Prof Foster discovered reports of more and more chips. Some were “hidden in plain sight”.

Up until his death in 1975, Mr Gray styled himself as the man who repaired the Stone of Destiny, but he never publicly revealed how many fragments he made.

Prof Foster is particularly interested in speaking to members of his family as they will likely be able to shed light on where some of the pieces are.

She is only completely sure about the locations of four fragments distributed by Mr Gray, who was influential in the Scottish Covenant Association which pushed for home rule.

While the stone itself is a particularly “unprepossessing” item, she argues that understanding the stories of these fragments adds a personal element to its narrative.

Prof Foster said: “It would be lovely to see more of these in the public domain and the stories being shared and celebrated.”

She has also tracked the fate of other, more official, fragments of the Stone of Scone which were taken as geological samples in the 19th century.

The Stone of Destiny was moved to its new home at Perth Museum last year, where it sits as the centrepiece of an exhibition on Scotland’s history.

When Charles was coronated in 2023 it was taken to London where it was mounted in the Coronation Chair, continuing its ancient role in the monarchy.

The 152kg sandstone block split in two during the famous Christmas Day raid of 1950, when four students spirited it back to Scotland to try and advance the cause of Scottish independence.

The repair work overseen by Mr Gray involved inserting three metal pins to help join the pieces back together, with a number of chips being created as a result.

The stone was recovered after a few months when it was left at Arbroath Abbey and the students who took it were never prosecuted – they maintained they were simply returning the artefact to Scotland.

Prof Foster can be contacted on her project’s website – thestone.stir.ac.uk – or via Stirling University.

+ There are no comments

Add yours