Tech

I install these 9 Python tools on every new machine

Everyone has their toolbox of favorite programs that they install on their machines whenever they get a new one. Working with Python, I’ve built up my own essential toolkit. Here are the libraries and programs I reach for whenever I get a new machine.

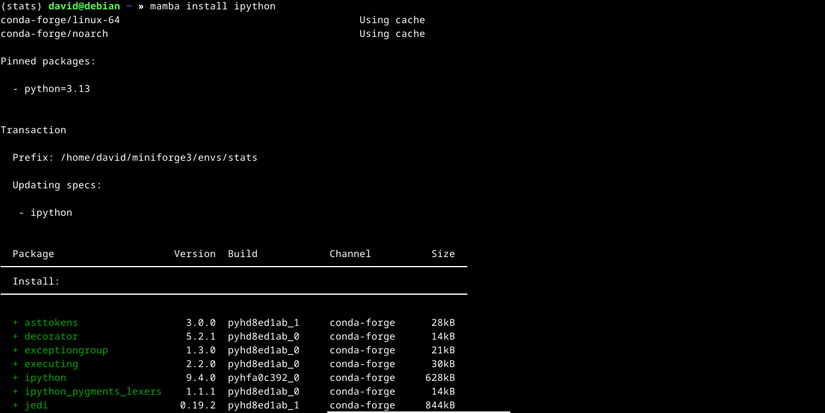

Jupyter/IPython

Jupyter is a way of creating interactive notebooks that blend text, graphics, and code. This is a unique form of programming. It’s taken the scientific programming world by storm. It’s so easy to run and re-run snippets of code.

While it’s not a Python-specific tool, supporting other languages, Python is one of the open-source languages of choice for scientific computing, including stats. Jupyter notebooks were originally part of IPython, which enhances the interactive Python environment. I mainly use IPython for experimentation and Jupyter notebooks when I want to save my results.

Mamba

This is not a specific Python tool, but Mamba is useful for setting up my environment on a new machine. While Python is included on many systems, on Linux systems, it’s mainly used for supporting scripts and other functions of the OS itself, and not meant for programming projects. If I want to install packages, I’ll have to either use my package manager or set up a virtual environment.

Mamba allows me to easily set up custom environments with the packages I want and switch back and forth. This makes it much less likely for me to mess up my system Python environment.

NumPy

NumPy is the workhorse of scientific computation on Python. Its functionality makes it comparable to Matlab, already widely used in science and engineering. It makes working with numerical arrays easy. You can define vectors and matrices to solve systems of linear equations easily.

The main attraction for me is the availability of a lot of basic statistical calculations, including the mean and median. NumPy also works with a lot of other libraries, which I’ll mention later.

SciPy

SciPy is a grab bag of a lot of scientific functions. Again, its main attraction for me is statistical computing. I can computer functions that for some reason aren’t in the standard NumPy. For example, I can compute the statistical mode, or the number that appears most often in a dataset.

Suppose I have an array called “a.” If I want to find the mode, I would just run this code:

from scipy import stats

stats.mode(a)SciPy also has many popular statistical distributions, such as the normal, binomial, and Student’s t. I don’t have to look through tables anymore.

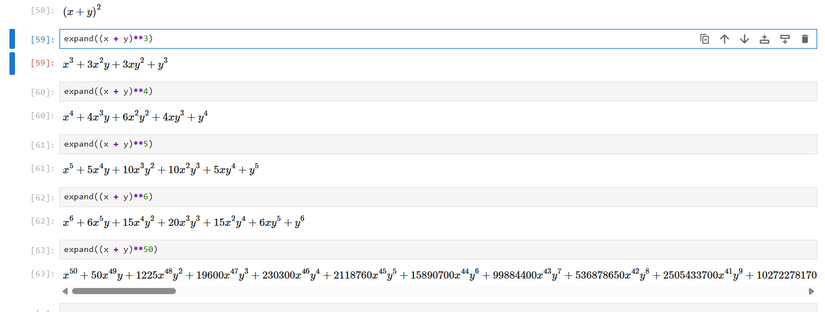

SymPy

While NumPy and SciPy cover numeric calculations, SymPy offers something completely different. It’s a library that turns Python into a computer algebra system. This lets it manipulate symbolic variables the way a calculator works on numbers. This is functionality that has been offered in expensive packages like Wolfram Mathematica.

This lets me perform algebraic operations within Python, such as expanding and factoring polynomials, solving equations, and even integral and differential calculus. While this accounts for a minority of daily operations, these are valuable for deeper understanding of statistical concepts. I can use it to work out the formula for a linear regression, while other libraries will handle the actual calculations. I’ve also been using it to work through texts that do make use of these more advanced operations. I’ve found it an invaluable tool for my mathematical self-education.

pandas

For statistical calculations, this would be even more of a workhorse than NumPy on its own. pandas makes it easy to define DataFrames of rectangular data. This resembles the arrangements of data you see in spreadsheets and in relational databases. It’s also trivially easy to import data from Excel and CSV spreadsheets.

Not only can I display data, it also has a lot of built-in functions to run calculations, such as descriptive stats. I can also plot data using pandas methods.

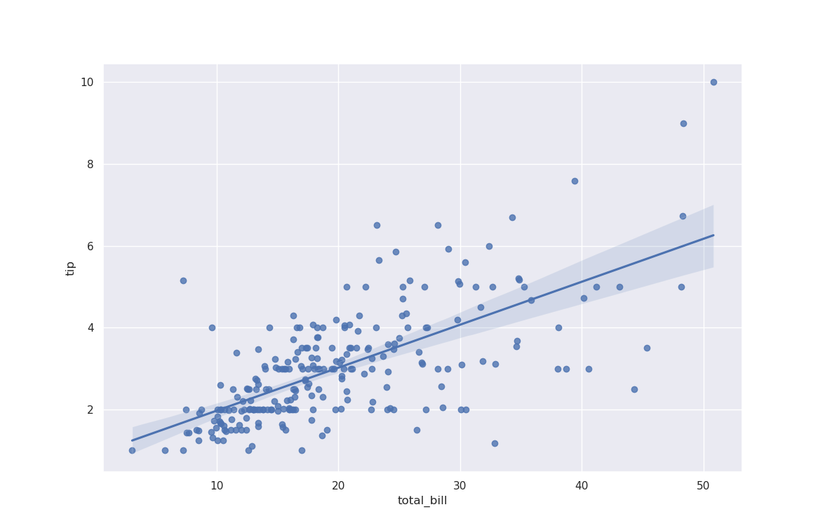

seaborn

I’ve mentioned Seaborn previously. I like how it offers an easy way to generate common statistical plots. It’s effectively a front end to the popular Matplotlib library. While the latter is useful, it can be a pain to set up the plot you want. In Seaborn, it’s mainly a matter of choosing the kind of plot I want and setting an x-axis and a y-axis.

For example, to obtain a regression with a scatterplot of the built-in restaurant tips database of the tip vs the total bill:

import seaborn as sns

sns.set_theme()

tips = sns.load_dataset('tips')

sns.regplot(x='total_bill',y='tip',data=tips)

Pingouin

Pingouin is a useful library for obtaining the results of statistical tests in a user-friendly way. To see the actual numbers behind that regression plot earlier, I can use pingouin’s linear_regression method:

import pingouin as pg

pg.linear_regression(tips['total_bill'],tips['tip'])There are other common tests, such as Student’s t-test and Chi-square.

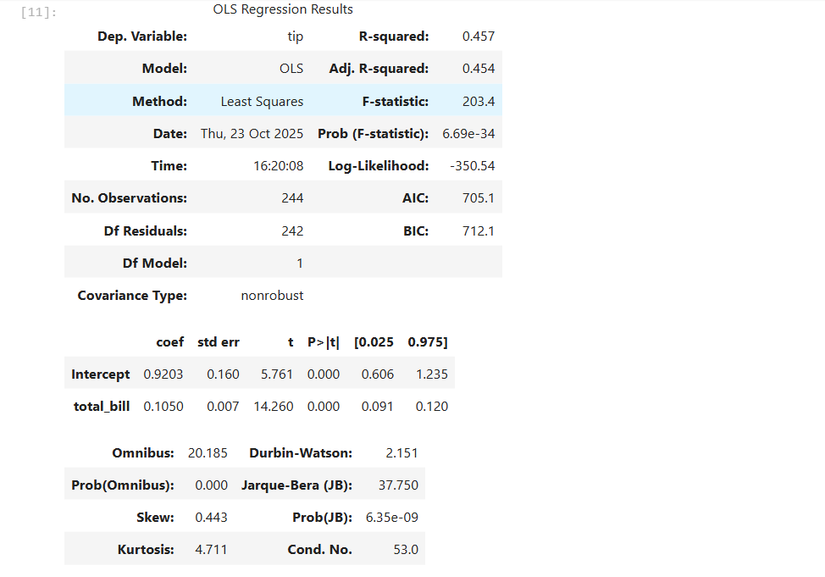

statsmodels

statsmodels is an older library that, as the name suggests, is mainly for statistical tests. Its main attraction is linear regression. Its results are also cross-checked against other statistical programs like R. This makes it useful if you want to make sure your results are valid. Speaking of R, it also supports R-like formulas. I’ll demonstrate this with another version of the regression analysis of the tips dataset:

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

results = smf.ols('tip ~ total_bill',data=tips).fit()

results.summary()These libraries and tools make analyzing data easier and even more fun. These will likely follow me to my next machine.