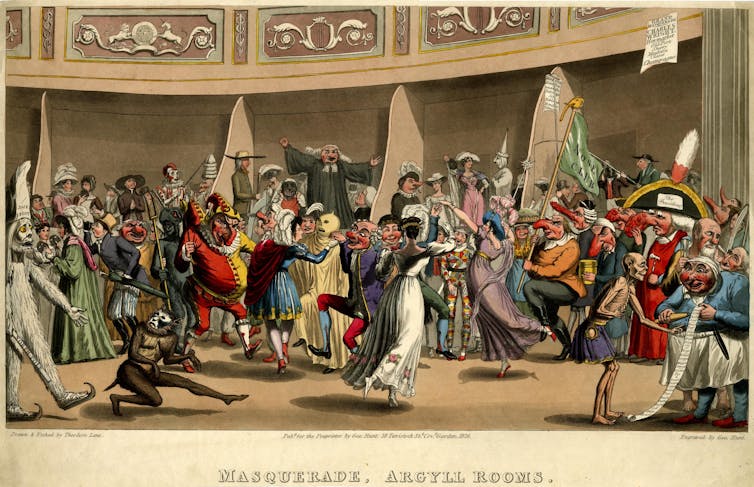

Countless love stories throughout the ages hinge on the idea of love at first sight. Immediate, unwavering infatuation the moment eyes meet. Two people finding each other across a crowded, glittering ballroom or perhaps bumping into each other accidentally. But what if your true love is hidden behind a disguise? And flees before you have a chance to learn their name?

Such is the challenge facing Benedict Bridgerton (Luke Thompson) in the most recent season of Bridgerton. The first episode of season four centres around a truly spectacular masquerade ball at Bridgerton House and sets up a re-imagining of the Cinderella story, with Regency flare.

Sparkling in silver from head to toe, servant Sophie Baek (Yerin Ha) manages to sneak into the lavish elite entertainment unnoticed. It is there she finds herself in the company of Benedict, one of the most sought-after bachelors in London and a notorious rake. Sparks fly as their gazes lock and the world fades away into a night of enchantment until the resounding chimes of the midnight hour cause Sophie to flee, leaving Benedict with no more than a fast farewell and sole silver glove.

Even without the concealment of a mask, Prince Charming had a hard enough time finding Cinderella – so what chance would mere mortals have had at finding missed connections, let alone true love at the masquerade?

In the case of real Regency woman Elizabeth Chudleigh, it was more like lust at first sight. Chudleigh, whose clandestine marriage was falling apart before her eyes, was an ageing maid of honour in the court of the Princess of Wales. One whisper of her despair, about her marriage or her age, would endanger her post in court, for, as attendants to the princess, maids of honour were expected to be young, unmarried ladies of repute.

As Chudleigh biographer Catherine Ostler explains, she needed to do something to grab the attention of eligible elite bachelors and the masquerade was the perfect place to do so. The masquerade offered the fashionable elite an exclusive space where they could flaunt their status, wealth, and taste through character, comic, or fancy dress.

Wiki Commons

Wearing a bold and breathtaking costume that exposed her breasts – or at the very least gave the illusion of nudity – Chudleigh took an enormous risk when she arrived at the King’s Theatre in 1749. Disguised as the mythical character Iphigenia, this daring decision boldly put Chudleigh’s sexuality, charms and body on display for all to see.

The author and politician Horace Walpole, who witnessed the dress, recalled in his correspondence that she was “so naked that you would have taken her for Andromeda”.

Luckily for Chudleigh, she became an overnight sensation and managed to catch the eye of one of the most powerful men in the country: His Royal Majesty, King George II. The king was besotted. Walpole himself saw George II fall head over heels, writing “our gracious Monarch has a mind to believe himself in love” with Chudleigh, which was most clearly made evident when he kissed her in front of his advisors.

Depictions of Chudleigh’s scandalous dress, or rather, undress, appeared in print shop windows across the country while reports of the risque costume circulated through correspondence and newspapers, such as the General Advertiser, across the country. Chudleigh herself appeared regularly at the king’s side. Though her position as mistress to His Majesty was relatively short-lived, lasting no more than a few years, her gamble at the masquerade not only aided her in climbing the social ladder and expanding her social circles, it inextricably linked her to the masquerade and transformed her from a maid of honour into a cultural phenomenon.

Smitten at first sight

James Hamilton, the sixth duke of Hamilton, had not imagined he would find himself utterly and completely intoxicated at the evening’s masquerade from anything other than copious amounts of wine, as was his tendency. He was 28 and still unmarried, despite his wealth and not unattractive features.

Scottish National Portrait Gallery

As he moved among the domino cloaks, harlequins and fancy dresses he spotted her, the rumoured beauty from Ireland, Elizabeth Gunning. She was striking. He was smitten – and he must marry her.

The thought, though impulsive, was not uncharacteristic of Hamilton who was known to follow his fancies – not unlike Benedict Bridgerton. The duke could not keep Gunning from his thoughts. Their paths crossed two weeks later at Lord Chesterfield’s where Hamilton was distracted beyond repair, making “violent love [with his attentions] at one end of the room while he was playing at pharaoh (cards) at the other end”. He subsequently lost £1,000.

In early February their met once again at a masquerade. Hamilton could no longer restrain himself and proposed that evening. Dressed as a demure Quaker, the flattered, and likely overwhelmed, Gunning accepted. Without a dowry to her name, Gunning had to rely on beauty, behaviour and a little luck to break the barriers of rank and marry significantly above her station.

The pair married in secret at a chapel two nights later, on Valentine’s Day nonetheless, before Hamilton’s family could interfere in this inferior match. The clandestine union was sealed at midnight with a bed-curtain ring, for Hamilton had forgotten to bring the proper one. The marriage, though rushed, was a small sort of happily ever after for Gunning, now the Duchess of Hamilton, who became a fashionable leading lady of the Georgian elite.

The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Not all Regency encounters had fairy tale, or even fanciful endings. Newspapers occasionally advertised missed connections at masquerades with clues including costume descriptions, initials and conversation topics.

In 1778, one eager gentleman addressed his note in The Morning Post to “A Lady in a light blue dress, and mask of the same colour, who was at the Pantheon Masquerade, and danced two or three dances” with him. She claimed she knew the gentleman she was keeping company with, having seen “him almost every day walking in Bond-street, or St. James’s-street, but would not tell who she was”. He requests that she “send a line to Stewart’s Coffee-house, Broad-street, informing him where is to be met with, it will be the means of quieting an anxious mind”.

Unlike Bridgerton’s Cinderella story, it is impossible to know whether or not this real pair found each other beyond the walls of the ball. One thing is for certain, however. True love at first sight–or true lust–is not the stuff of fairytales alone, though it may be harder to find when its wearing a mask.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.