The kidnapping of Nancy Guthrie – the mother of US news anchor Savannah Guthrie – is the latest in a string of crimes where ransoms have been demanded in Bitcoin.

The 84-year-old was kidnapped from her home in Tucson, Arizona, in the middle of the night. A ransom of US$6 million (£4.4 million) has been demanded by the kidnappers.

The scale of the ransom demand, combined with the use of cryptocurrency as the payment mechanism, raises a critical question: although Bitcoin is not inherently untraceable, can the perpetrators ultimately profit without being identified?

Bitcoin is a decentralised digital currency, commonly referred to as a cryptocurrency, and is often believed to be anonymous, private and untraceable.

This perception has made Bitcoin attractive to some criminals, who view it as a convenient mechanism for receiving, transferring and storing payments.

As a result, Bitcoin has become increasingly associated with criminal activity, including extortion, kidnapping, fraud, ransomware and even murder.

The Guthrie case has once again drawn attention to the darker associations surrounding Bitcoin and reinforced public anxiety about cryptocurrency and its use for nefarious purposes.

At the same time, a number of high profile kidnappings around the world in 2025, involving people known to hold cryptocurrency, has intensified these concerns.

A common perception is that, because Bitcoin is digital, tracking transactions is difficult. Bitcoin does not exist in a physical form; it is represented as entries on the Bitcoin blockchain – a decentralised ledger used to record transactions across a network of computers. So Bitcoin is not inherently untraceable; its blockchain is transparent and permanently recorded.

Transactions do not explicitly list names, but each transaction is publicly visible and traceable between wallet addresses. Ownership is controlled through private keys and managed via a “digital wallet”, which functions conceptually like a traditional wallet in that it stores and enables the transfer of value. Thus, Bitcoin is more accurately, pseudonymous, not anonymous.

Currency conversion

In the Guthrie case, the immediate practical challenge for the kidnappers would be converting US$6 million into Bitcoin and transferring the cryptocurrency to a digital wallet. From there, the funds would need to be sent to a wallet address specified by the perpetrators – assuming the kidnappers provide such an address.

Transactions conducted through regulated cryptocurrency exchanges that impose know-your-customer checks may expose participants. These checks are mandatory processes to confirm user identities with official IDs, proof of address, and facial recognition.

Even before the funds reach the kidnappers, the transaction through a cryptocurrency exchange may itself create identifiable records. However, there is no guarantee of this, as there are many unregulated exchanges that operate in jurisdictions with lenient legislation.

Alamy (AP)

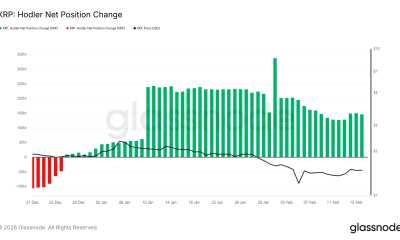

While Bitcoin transactions are traceable between wallet addresses, the kidnappers in this case may attempt to enhance anonymity through layered technical measures. These may include generating a new wallet address for each transaction, operating multiple wallets, and repeatedly transferring funds from a primary wallet through successive intermediary wallets to obscure transaction links.

Maintaining anonymity also requires avoiding any association between wallet addresses and personal information, refraining from interacting with other identifiable people, and using privacy-enhancing tools such as Tor/VPNs – software that masks a user’s location – and coin-mixing services, which enhance privacy by scrambling cryptocurrency funds with others to obscure links between senders and receivers.

Achieving this level of operational security demands significant technical knowledge and strict discipline from the kidnappers. Any human error, whether through identity exposure, exchange interaction, IP logging, or conversion into hard cash may compromise anonymity.

Ultimately, the critical issue is not merely tracing funds but determining how recipients convert or use the Bitcoin without triggering identification through regulatory checkpoints, forensic analysis, or operational mistakes.

Even if the US$6 million could be traced between wallet addresses, anonymity hinges on whether those addresses can be linked to real-world identities. Where wallet holders remain unidentified and operate outside regulated exchanges, investigative challenges increase.

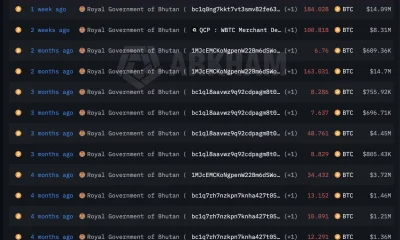

Additional complications arise if the perpetrators operate outside the US. Cross-border enforcement faces limitations including variation in crypto-related legislation and regulation, uneven training in tracing and confiscation, and limited international coordination.

Whether perpetrators can ultimately be reached by law enforcement depends significantly on their jurisdiction and the degree of international cooperation.

![CPI is OUT! The Market Reaction Explained [Bitcoin & Stocks]](https://wordupnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1771536648_hqdefault-80x80.jpg)