Politics

Climate cooperation, devolution, and the difficulties for left-behind places around climate policy

Patrick Bayer and Federica Genovese argue that while communities exposed to climate mitigation are afraid of net zero, some might be more interested in international climate cooperation than you think.

As delegates depart COP30, ten years after the Paris climate agreement, debates over the feasibility and relevance of international climate cooperation are sharper than ever. The past months have seen an intensifying ‘greenlash’: political resistance to climate policies and climate science, surges in support for anti-green parties across Europe, and renewed scepticism about global climate institutions.

Various commentators, including the United Nations and Prime Minister Starmer, have suggested that ambitious climate cooperation is becoming politically ever more difficult and that the “consensus is gone”. Pessimism is especially stark in places that have seen their industrial base decline. These regions, think of oil rigs in the North Sea or coal mines in Northern Spain, have long been feeling left behind by economic and political change that is fast-tracked by rapid decarbonisation.

Despite the gloomy picture, new evidence from our research suggests a more nuanced view about the place-based politics of climate cooperation. In a new British Journal of Political Science article, we document that, rather than being inherently opposed to climate action, some of the communities most exposed to the costs of decarbonisation may actually be open to climate cooperation after all. However, only if they trust the authorities involved in converting climate policy into practice.

Our argument enriches and complicates the standard narrative, which holds that regions reliant on fossil fuels or heavy industry instinctively reject far-reaching climate policies because they face disproportionate adjustment costs. These concerns often translate into mass scepticism not just towards domestic green measures, but also towards international climate institutions, which can appear remote, unaccountable, and insensitive to local realities. Yet, other research shows that economic exposure alone does not determine people’s views. What matters equally, if not more, is the local political context. In particular, we interrogate the importance of whether people believe their region has a meaningful voice in decision-making and whether they trust the institutions that implement climate policy.

To explore this, we surveyed citizens in three parts of the UK that share vulnerability to climate policy costs but differ substantially in their political structures: Yorkshire & Cumbria, Scotland, and Wales. All three regions have experienced industrial shifts and, notably, energy transitions; consequently, they understand first-hand the material challenges associated with the green transition. However, these places differ in the levels of political autonomy and institutional trust, with support for Westminster holding responsibility for climate policy being much lower in Yorkshire (45%) compared to Wales (63%) and Scotland (70%) according to 2019 Eurobarometer data. This divergence allows us to examine how regional governance shapes attitudes toward international climate cooperation.

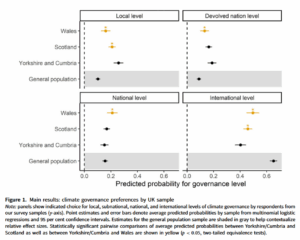

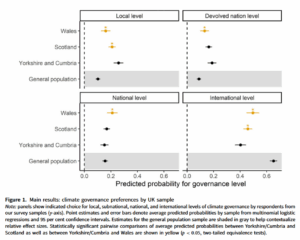

We ran the same survey that asked respondents to rank their preferred level of climate governance between local (city/town), devolved, national and international level together with a battery of questions about respondents’ general political attitudes, basic demographics, and their perceptions on climate change. The differences in responses were stark.

In Yorkshire & Cumbria, where regional political authority remains weak and where feelings of underrepresentation vis-à-vis Westminster have been long-standing, respondents were the most sceptical of international climate governance. Many viewed international climate efforts as external impositions that risked further damaging their region’s economic prospects without offering clear channels for local influence or accountability. In contrast, respondents in Scotland and Wales — both with devolved parliaments and more established regional governance — expressed considerably more openness to international climate cooperation, despite facing similar economic vulnerabilities.

By ruling out a vast range of alternative explanations that could drive these differences, such as variation in income levels, devolution preferences, or rural-urban make-up across the samples, these findings are consistent with our argument that greater trust in devolved institutions translates into a greater belief that international climate action, when mediated by credible regional authorities, can bring benefits such as investment, development, and regional empowerment. Support for climate cooperation in all these regions is, however, weaker than the national average because of the adjustment costs these regions face from ambitious climate action.

Figure 1: Preferences for climate policy to be governed at the local, devolved nation, national and international level for respondents from Wales, Scotland, Yorkshire and Cumbria, and a general population sample.

Some respondents in Scotland and Wales even associated international climate institutions with opportunities to assert a distinct regional voice, suggesting that the legitimacy of climate cooperation can be enhanced when people feel their political community is recognised and empowered within multi-level governance. These patterns were especially pronounced on climate issues, more so than for trade or other international policy areas, highlighting the unique political dynamics of climate governance.

This has important implications for climate politics in 2025, at a moment when international climate cooperation is simultaneously urgent and contested. Global attention has been focused on COP30 in Brazil, however real progress is made at home. The success of international climate action depends as much on domestic political trust as on diplomatic bargaining. Our findings suggest that declining carbon-intensive regions are neither inherently nor homogeneously hostile to climate cooperation. Their attitudes are conditional: when they distrust national elites or feel bypassed by decision-makers, scepticism grows; when they trust regional institutions and see credible pathways for representation, support for climate action increases.

As populist far-right parties across Europe, including the UK, increasingly seek to mobilise greenlash sentiment by pitching climate action as an elite-driven, externally imposed burden, the evidence from our research indicates that these narratives may resonate in some communities more than others depending on the strength and visibility of regional institutions and programmes.

This underscores a critical policy lesson. The legitimacy of climate cooperation, whether through the EU or broader international partners, hinges not only on economic support packages or technological solutions, but also on institutional trust and regional political voice. Strengthening devolved communities, ensuring meaningful regional participation, and demonstrating responsiveness to the specific challenges faced by vulnerable communities can help build the social foundations for a durable green transition.

As the future of climate cooperation depends fundamentally on the distributional politics within countries, it is critically important to understand whether people in left-behind regions – from former coal communities in the South Wales valleys to declining coal regions in Central Europe – feel that the transition is something done with them rather than to them. Our findings suggest that when trust and representation are politically credible, these communities may be far more supportive of ambitious climate action than the current climate of greenlash implies.

By Patrick Bayer, Professor, University of Glasgow and Federica Genovese, Professor, University of Oxford.