Politics

Is economic security a missing element of EU-UK cooperation?

Jake Benford and Anton Spisak argue that there is a strong case for the UK and EU to cooperate more closely on questions of ‘economic security’.

When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen met UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer at Lancaster House in May, they pledged a ‘new chapter’ for EU-UK relations. This included a Security and Defence Partnership (SDP) and a long list of areas for negotiations, including on agrifood (or SPS) standards and energy cooperation. And yet one topic that increasingly shapes how Brussels sees the world barely made the agenda: economic security.

One reason for this might be the lack of a joint definition. To some, it means defending against any kind of risk in the global economy: supply-chain disturbances, technology theft, or overt economic coercion. To others, it entails doing more to secure competitiveness in an increasingly contested environment, using tools that range from subsidies to regulatory standards.

In policymaking, the line between the two is often blurred. The act of reducing vulnerability is also a way of shaping who sets the rules; the act of promoting competitiveness is often justified as a security imperative. Economic security is less a new policy area than a new frame – a recognition that the separation between commerce and strategy belongs to another era.

The EU’s economic security turn began with its 2023 Economic Security Strategy that gave expression to anxieties that had been building since China’s growing assertiveness, the pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. What followed were a suite of new policy ‘tools’, from the Anti-Coercion Instrument to a tighter investment-screening framework. Most recently, the Commission published its communication – or ‘doctrine’ – on economic security. It promised to use its array of regulatory tools ‘more strategically’ to pursue both defensive and offensive objectives.

The UK’s approach, by contrast, has been more cautious. While the 2021 National Security and Investment Act gave ministers new powers to intervene in the economy on national-security grounds, successive governments have largely resisted the broader protective posture that has taken hold in Brussels.

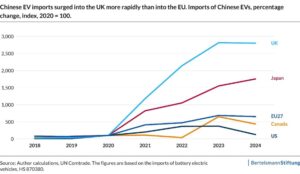

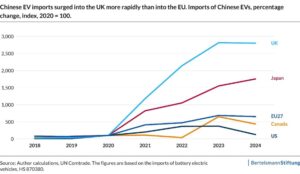

For example, when Brussels imposed protective tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles in 2024, London chose not to follow suit. The paradox is that the UK was more exposed, not less: imports of Chinese EVs grew four times faster into the UK than the EU (figure 1). The decision may reflect different priorities, but it also illustrates how two highly integrated markets can face similar risks with different instincts.

Figure 1

There are, however, signs of change. When the Labour government published its long-awaited Trade Strategy in July, it announced plans for a new trade defence instrument, reforms to the Trade Remedies Authority, and an ‘economic security advisory service’. This suggests a more proactive mindset, even though implementation has been slow.

Cooperation with the UK also feels curiously thin when compared with other EU partnerships. The EU has woven a dense network of ‘mini-deals’ with other countries – on digital policy, critical raw materials, and other aspects of economic security (figure 2). These differ in ambition, but they all increase resilience through deeper cooperation between ‘like-minded’ partners. The UK has been mostly absent despite being the EU’s second-largest trading partner after the US.

The SDP commits both sides to ‘explore ways to exchange views on external aspects of their respective economic security policies’. Indeed, informal exchanges are already taking place through diplomatic channels. But the question is whether this is sufficient in a global economic environment of permanent volatility.

Figure 2

Trade data underlines the rationale for deeper cooperation. Our recent empirical analysis points to a striking overlap in shared vulnerabilities. Both sides are highly exposed to potential supply shocks: nearly a fifth of EU imports and around 15 % of UK imports by value come from ‘dominant suppliers’ – trading partners that account for at least 50% of imports for specific products. In most cases, that supplier is China (figure 3).

For more than 7% of imports by value, the EU and the UK rely on the same ‘dominant supplier’ for the same products. China again features most prominently. These dependencies span everyday consumer goods such as electronics, but also extend – more worryingly – into sensitive areas, from solar panels and lightweight drones to a range of critical minerals.

For policymakers who still see economic security as a fashionable overlay on ordinary trade policy, this is the kind of statistic that should sharpen attention. If both sides are trying to diversify suppliers and prepare for disruptions, they are more likely to succeed where their strategies are aligned. There is little strategic value in two like-minded neighbours scrambling independently for the same alternative suppliers, or duplicating intelligence-gathering on the same risks.

Figure 3

The overlap also extends to ‘offensive’ interests. Consider the Commission’s ambition to develop more ‘structured cooperation’ with the 12-nation Asia-Pacific trade bloc, CPTPP. The UK, as a CPTPP member, could support this and ensure that European and British efforts in the fragmenting global trading system complement each other.

The challenge for the post-Brexit relationship, then, is to turn these shared interests into instances of practical cooperation.

There have already been examples of quiet success. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EU and UK have successfully coordinated their sanctions regimes and closed loopholes. This work has often been technical and discreet. But it shows what is possible when the strategic imperative is clear. The same logic could be extended to other areas: coordinating export-control lists on sensitive ‘dual-use’ items; sharing intelligence that supports FDI screening; or joint monitoring of critical supply chains.

What might enable deeper cooperation is a forum that elevates these topics to a political level. Many conversations already take place between officials – particularly through ‘specialised committees’ under the TCA – but these may not be frequent enough or at the right level. One possibility would be to create a new EU-UK Economic Security Dialogue bringing together the EU trade commissioner and UK business and trade secretary on a regular basis. Its function would be to inject greater political momentum into this shared agenda.

The more immediate opportunity may lie in the talks already underway. Both the SPS and energy negotiations carry questions about shared resilience, security of supply, and dependence on specific third-country inputs. Embedding the economic security dimension in these talks could be a good place to start.

Inevitably, deeper cooperation would require greater political alignment on bigger questions of the day – particularly policy towards Washington and Beijing. But this seems implausible in the short term, not least when Brussels itself struggles to reconcile competing national priorities.

The solution is not to pretend the differences do not exist. Rather, it is to isolate the areas of clear common interest and build trust through practical cooperation, which might in turn make the tougher conversations easier.

Without closer cooperation, one thing is clear: the EU and the UK will keep confronting the same threats with little alignment. That will leave both less resilient and less influential – something neither side can afford.

By Jake Benford, Senior Expert, Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Europe Programme and Anton Spisak, Associate Fellow, Centre for European Reform.