Politics

Labour burnishes its Brexit credentials

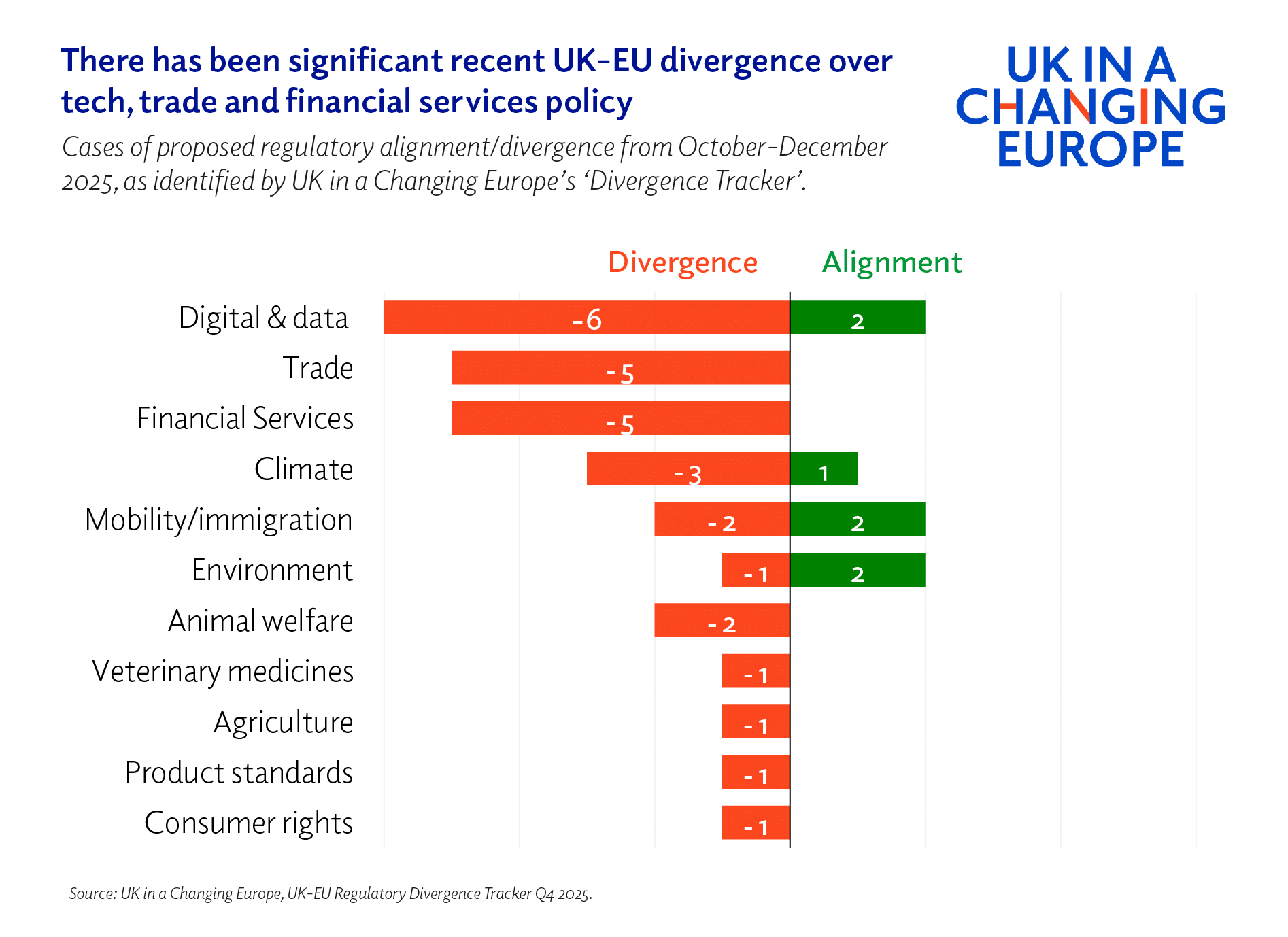

Based on the most recent edition of the UK-EU Divergence Tracker, Joël Reland argues that, despite rhetoric about aligning more closely with the EU, Labour has in fact diverged more strongly from EU rules than previous Conservative governments.

It is something of a paradox that, for all this government’s talk of closer alignment with the single market, it is doing a better job than its predecessors of delivering divergence from EU rules.

The evidence is found in our new divergence tracker which shows that, while Labour has significantly scaled back the number of attempts at divergence overall, clear plans are emerging in a few select areas. And it is the smaller scale of Labour’s divergence agenda which makes it more effective.

The Conservative strategy suffered from being far too expansive. Its 2022 policy paper on the potential ‘Benefits of Brexit’ ran to 105 pages and covered almost every possible policy area – lacking any sense of strategic prioritisation or overriding philosophy.

Meanwhile, a plan to let all EU law expire by default under the Retained EU Law Bill (before Kemi Badenoch abandoned it, decrying it as an act of arson), left officials scrambling to work out which rules to retain, rather than developing well-honed plans for divergence. This fixation on the quantity, rather than quality, of divergence meant resources were spread far too thinly to deliver any proper programme of reform.

Labour’s plans are, by contrast, more targeted and better defined. On goods, where the majority of UK exports go to the EU and the barriers to trade created by Brexit are greatest, the government is generally seeking closer alignment with EU rules. Whereas on services, where UK exports are oriented more towards the rest of the world, there are some attempts to do things differently.

Take financial services. We have identified four cases over the past quarter of the UK reforming EU-era rules in order to reduce compliance costs for firms. On the controversial practice of short selling (which precipitated the 2008 crash), the UK is moving closer to the US model of anonymising disclosures – so major bets made by financial firms against other companies will no longer be made public. The government has also reduced the level of reporting obligations on companies in relation to transactions, operations and investment advertising. The argument is that cutting back firms’ admin costs will spur economic growth.

Previous Conservative administrations also sought to create leaner regulatory architecture for financial services – initiating multiple reviews to that end – but delivered relatively few concrete reforms (the removal of the bankers’ bonus cap being a rare exception).

It’s still early days for this government. A few lighter reporting obligations will not attract swathes of new investment to the City of London – but they are starting to draw a clearer regulatory divide with the EU. The Commission is also focused on increasing the ‘competitiveness’ of its financial sector but is opting for model based on greater EU-level regulatory harmonisation and oversight – rather than cutting back on red tape.

A similar divide is emerging on tech. One of the most striking findings of the latest tracker is that the Commission has, in the last quarter, made five separate interventions against US tech companies for violating a range of rules related to digital competition and safety – with more in the pipeline. This has led to a strong backlash from the US government, which has accused the EU of ‘regulatory overreach targeting American innovation’ and threatened trade retaliation.

Despite having similar regulations in place, the UK has made only one equivalent intervention, opening an investigation into X’s ‘Grok’ AI feature under its Online Safety Act. When it comes to digital markets rules – designed to prevent big tech abuse of dominant market positions – the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is yet to open a single investigation. This follows a ‘strategic steer’ from government for the CMA to take a less interventionist stance, further reflected in it having not blocked a single merger in 2025 – the first time this has happened since 2017. The UK has also taken a more hands-off approach to AI rules.

This approach is part of a wider foreign policy strategy to remain on good terms with the United States in the hope of extracting trade concessions (or at least avoiding new tariffs). As well as treating US tech firms more leniently, the UK has (like some other countries) promised greater NHS spending on US pharmaceuticals in the hope of having UK pharma exports to the US zero-rated in return.

And yet, despite a clearer strategy for divergence emerging, it is far from clear that it will deliver significant benefits in practice.

Promises that deregulation will revitalise the economy seem optimistic. Plans to cut back ‘red tape’ on companies have been tried by every government this century – right back to Tony Blair – and have never ‘turbocharged’ growth in the way the Chancellor claims it will.

The scale of UK divergence remains relatively small-scale, and we are yet to see evidence that the UK can really become a ‘hub’ for international investment in AI, tech or financial services through a lighter rulebook. Moreover, the EU is also seeking to lighten a range of regulatory burdens on firms through its ‘Omnibus’ proposals, potentially dulling any slight competitive edge the UK might get.

Trying to appease the US through lighter-touch tech regulation also seems a risky ploy, given how unpredictable the US President is. Both the UK-US tariff and pharma deals are yet to be formalised, while, until recently, the UK was facing the prospect of additional 10% tariffs for supporting Greenlandic sovereignty. The reported US demand that the UK relax food regulations (which would torpedo the proposed UK-EU ‘SPS deal) in exchange for a digital trade deal is further evidence of the difficulty in balancing EU and US interests.

Labour is starting to deliver the regulatory ‘benefits of Brexit’ which the Conservatives promised – but failed – to realise. The problem for the government is that the likely gains from this agenda appear rather slim. And if it cannot demonstrate clear economic benefits from Brexit, calls to move closer to the EU are likely to grow stronger.

By Joël Reland, Senior Researcher, UK in a Changing Europe.